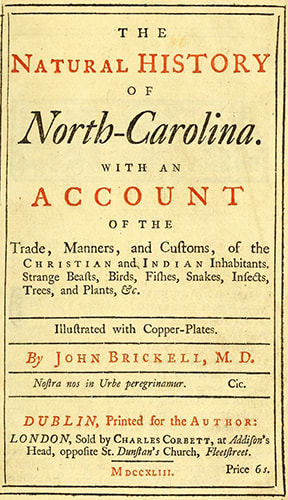

Continuing my deep dive into the enslaved man referred to in John Custis IV’s Commonplace Book (CPB) as Dr. Pawpaw, which you may remember from parts one and two of my blog series Finding Dr. Pawpaw, I found that John Custis IV was not the only person to record Dr. James Pawpaw’s remedy for yaws, a disease once common to the southern American colonies. The remedy also appears in John Brickell’s 1737 book, The Natural History of North Carolina (Fig. 1). Compared with the Custis CPB, I found that Brickell makes no mention of Pawpaw while Custis introduces the remedy “Dr. Pawpaw’s Remedy for Pox or Yaws.” Beyond the omission of credit in Brickell’s book, some of the ingredients have been substituted for others along with the methods for applying them. Both Brickell and Custis recommend ingesting a sumac-based decoction.

Brickell used sumac “that bears the Berries” (This can only be staghorn or smooth sumac; other species don’t have berries). Although Custis doesn’t mention berries, in 1738 we have a record that dealt with “sumach that produced tufts of a very bright scarlet” with the tufts probably being berries (Fig. 2). Brickell’s remedy has instructions to make the decoction, when and how to take it, and how to use it to wash external sores. The Custis Commonplace Book includes additional instructions to wash sores in the mouth and took a very different approach to treat external sores.

The ingredients used in the decoction are native to areas in the colonies--but on the chance that Pawpaw was a first-generation enslaved man from another part of the world, how would he have known which local ingredients to use? West Africa has a climate similar to the American mid-Atlantic, so it’s certainly possible that enslaved people recognized acceptable counterparts to medicinal plants from their native lands--but it’s just as likely that the information may have passed to him from local Native peoples with intergenerational knowledge of the medicinal uses of plants int the region. Sharing of information between enslaved people and Native Americans was not uncommon, and sumac has a long history of use by many Native peoples, including the Natchez, Cherokee, and Creek, who used parts of various species of sumac to treat everything from boils to dysentery. Other common ingredients used by Native peoples in pre-contact America include pine bark and Spanish oak. Sumac, Spanish oak, and pine all have one thing in common: they all contain a substance called tannin, a type of astringent that acts as an anti-inflammatory and promote the formation of new tissue. Custis’ version of Dr. Pawpaw’s remedy recommends:

“…if he has outward sores he must keep them perfectly clean wth a solution of ye blew Stone and yn anoint ym wth deer or hares dung and turpentine; made into an oyntment wth oyl of Rattlesnake…”

The ingredients are made into an ointment and applied to lesions associated with Yaws or other “pox.” Turpentine was commonly sold in apothecaries, but it is obtained from the resin of pine trees (recall that pine bark is used in the decoction and historically by Native tribes). Deer or hare dung might only be seen as medicinal if a person is familiar with the diet of those animals. If they ate a plant with medicinal properties, logically, their dung should have medicinal properties carried by the plants they consumed.

Rattlesnake oil and hogs lard seem to be equivalent, but rattlesnake oil is the preferred ingredient in Dr. Pawpaw’s topical remedy for yaws. The main purpose of these ingredients is likely to act as a carrier, making these ointments easier to apply to wounds. But rattlesnake oil, made from the fat of the snake, was thought to have properties that aided in the relief of joint pain, similar to, but not as effective as, Chinese water-snake oil introduced to America by Chinese immigrants in the mid-19th century—well after the lifetimes of Dr. Pawpaw and John Custis IV. The apocryphal history of the medical uses of rattlesnake oil to treat joint paint (incidentally, a common symptom of yaws) holds that the knowledge was shared in the American West by a Hopi tribal member with Clark Stanley, a man who, in the 1890s, would come to be known as the “Rattlesnake King” for his promotion of “Stanley’s Snake Oil.” While this is likely a sales tactic, rattlesnakes, common throughout America would have been a familiar sight to Native peoples and any medicinal properties they offered may have been well known by the time of European colonization.

Conclusion

Let’s sum everything up and look at the timeline surrounding Dr. James Pawpaw. The earliest mention I have found of him is on April 29th, 1729 in the Executive Journals of the Council of Virginia. He was “given his freedom” but still required to stay under government direction “untill he make a discovery of some other secrets he has for expelling poison, and the cure of other diseases.” When word got around about Dr. Pawpaw’s success in treating a group of enslaved people in 1730, many patients began seeking his cures. A version of Pawpaw’s remedy appears in Brickell’s book published in 1737. Custis’s version of the remedy appears to have been recorded between 1738 and 1749. Let’s also recall from part one of this series that Custis recorded another remedy for yaws after Dr. Pawpaw’s, maybe suggesting Pawpaw’s remedy wasn’t working for Custis’s purposes. With the difficulty of differentiating between yaws and syphilis, Custis may have been confused about which disease he was encountering and which remedy to use.

After implying Dr. Pawpaw’s remedy was better at curing the pox than yaws, Custis goes on to say:

“this medicine will cure ye dropsy and is essentiall against poison, but in these cases few [experiments] have yet bin made, except by Doctor Pawpaw himself.”

Take this last line and think of Pawpaw’s life after being “freed” by Governor Gooch. Pawpaw was forced to remain in contact with the government while he searched for or developed additional cures. During that same period, Custis sat on the Governor’s Council and would certainly have been among the people with inside knowledge of Pawpaw’s medicinal experiments and successes, and notably, Custis did bestow James Pawpaw with the title of “Doctor” when no one else did. Custis also indicated that experiments had only been made by Pawpaw, which may signify some sort of personal familiarity between the two men. A law passed in 1723 made it harder to free enslaved people; dictating that no slave would be set free unless they had performed a service deemed beneficial to the colony. During the nearly 60 years that the law was in place, fewer than 25 enslaved people were legally given their freedom in Virginia, and James Pawpaw was, at least in a sense, among that number.4

Emily Zimmerman is an archaeology lab technician with the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeology. In addition to her work transcribing and researching the remedies recorded in the Commonplace Book of John Custis IV, Emily works tirelessly cataloging the many artifacts uncovered at Custis Square.

References

- Breslaw, Elaine G.

2014 Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America, NYU Press. Accessed May 22, 2020. - Brickell, John

1737 The Natural History of North Carolina, Johnson Publishing Company.

Accessed 26 May 2020. - Chappell, Gordon W. (editor)

2000 Southern Plant Lists, Southern Garden History Society, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Accessed 27 May 2020. - Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

2020 The Business of Freeing a Slave in Virginia. The American Revolution, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Accessed 27 May 2020. - Encyclopedia Britannica.

Encyclopedia Britannica, “Middle Passage”. Accessed 21 May 2020. - McIlwaine, H.R. (editor)

1930 Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia Vol. IV, Virginia State Library, Richmond VA. Accessed 26 May 2020. - Parish, Susan Scott

2012 American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World. UNC Press Books. Accessed 22 May 2020. - Parramore, Thomas C.

1971 The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 48, No. 1, The “Country Distemper” In Colonial North Carolina. North Carolina Office of Archives and History. Accessed 21 May 2020. - Paugh, Katherine

2014 Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 88, No. 2, Yaws, Syphilis, Sexuality, and the Circulation of Medical Knowledge in the British Caribbean and the Atlantic World. Johns Hopkins University Press. Accessed 21 May 2020. - Schiebinger, Londa

2017 Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, Stanford University Press. Accessed 22 May 2020. - Taylor, Lyda Averill

1940 Plants Used as Curatives by Certain Southeastern Tribes, Botanical Museum of Harvard University, Cambridge MA. - WHO

2019 Yaws. Accessed 21 May 2020. - Zuppan, Josephine Little (editor)

2005 The Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717-1742. Rowman & Littlefield. - Edwards-Ingram, Ywone

2005 Medicating Slavery: Motherhood, health care, and cultural practices in the African diaspora. College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences. Accessed 3 June 2020.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.