A former Colonial Williamsburg archaeologist told us at the beginning of our excavations at Custis Square, “There’s nothing left to find.” He couldn’t have been more wrong. After three years of excavation, we have discovered the outline of the central portion of John Custis’ famous garden. We have also recovered over 247,000 artifacts that speak to life on this property going back thousands of years--and we’ve still got two years of excavation ahead of us.

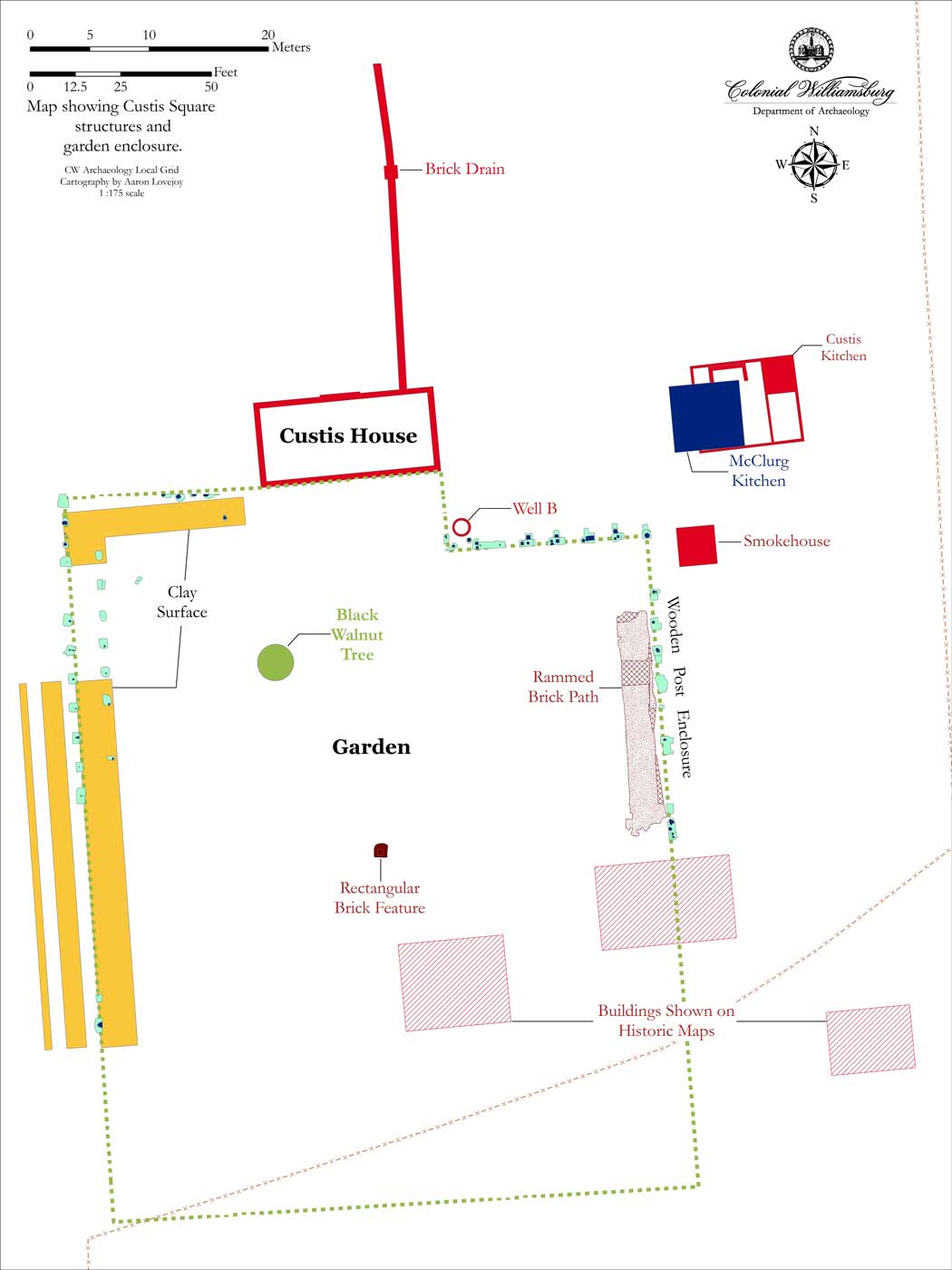

Throughout 2021, we focused our excavation efforts on understanding a series of very large postholes that extend out from Custis’ house. The more we dug, the more these 3ft x 3ft square holes appeared. As we connected the dots, a pattern emerged, showing us that these holes represented what must have been an enormous wooden fence enclosing a portion of the garden (Fig 1). In fact, there was still intact wood in some of the postholes after 300 years in the ground. We identified the wood as eastern red cedar, an incredibly durable wood, but not one normally used for fences. The fence connects the garden to John Custis’ house and stretches south for 200 feet. This enclosure was 160 feet wide with the house centered on its northern edge, creating almost 32,000 square feet of garden space. Looking north from the front step of the house Custis would have had a view directly to Bruton Parish and, to the south, his house opened directly into the garden. While we have few details to tell us what the house looked like, documentary clues tell us that it had a central entrance and hallway passage. This means that the main access into the garden would have been through the central hall, making it an exclusive space where he might have spent time privately or with his close friends.

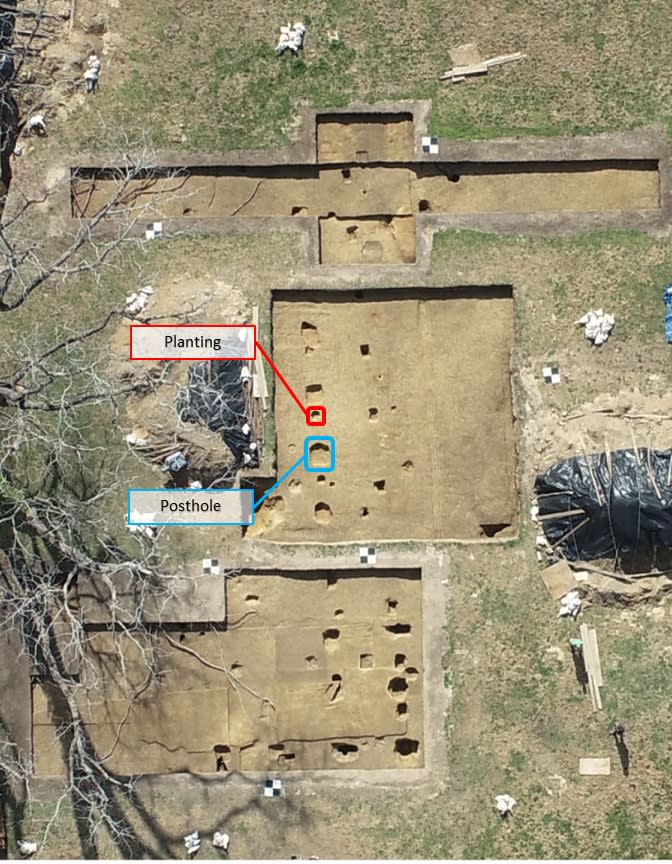

Since discovering the “bones” of the central garden, we have shifted our efforts, looking inside the enclosure to try and find patterns of plantings and garden features that will allow us to reconstruct this space. At the end of 2021, we opened up two large excavation areas to see what more we could find, and we were not disappointed. Exactly 100 feet south of the house and directly in the center of the garden, a rectangular feature was found. It is still unclear what this feature was, but it is tantalizing to think that it may be related to one of the three leaden statues of Apollo, Bacchus, and Venus that were said to have adorned the landscape. Small irregular stains in the soil, which we believe to be remains of garden plants, also began to show up on regular 8- and 12-foot intervals around this central feature. Now that we’re beginning to see patterns among the plantings and other ornamental features, our next steps will be to expand on these two large excavation areas and look for a broader understanding of the landscape design within the garden’s wall.

The garden discoveries didn’t stop there. We also discovered a regular series of planting holes paralleling the garden fence (Fig 2). Just beyond that – a series of shallow fence posts with planting holes in between. The configuration of these features strongly suggest the presence of espaliered plants. This is a process of training a plant’s limbs to grow horizontally along lines usually attached to garden walls or in between fence posts.

Also, while we were tracing the large postholes that turned out to be the boundary for John Custis’ enclosed garden, we ran into an unexpected discovery at the enclosure’s southwest corner. Where we expected to find the southern fence line, we instead ran across a deep pile of underfired bricks layered with dense clay (Fig 3). This is almost certainly associated with the brick kiln where the bricks for Custis’ house were made, perhaps as early as 1714 or 1715. The bricks are likely the demolished remains of the kiln itself and the layers of clay are the left-over raw material from the manufacturing process. Very little architectural evidence for the house remains, so it was amazing to find that evidence of its construction was still intact and just under our feet.

Last November, the site was closed for the winter, allowing us to open the two large excavation areas that have given so much information over the last few months. If you spent the winter peeking through the fence, trying to get a better look at what we’re finding at Custis Square, the wait is finally over--we’ve thrown our gates open and are excited to welcome visitor back to the site for exploration and guided tours and there’s a lot to see. So, next time you’re in the area, stop by, say hi, and see what’s new!

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.