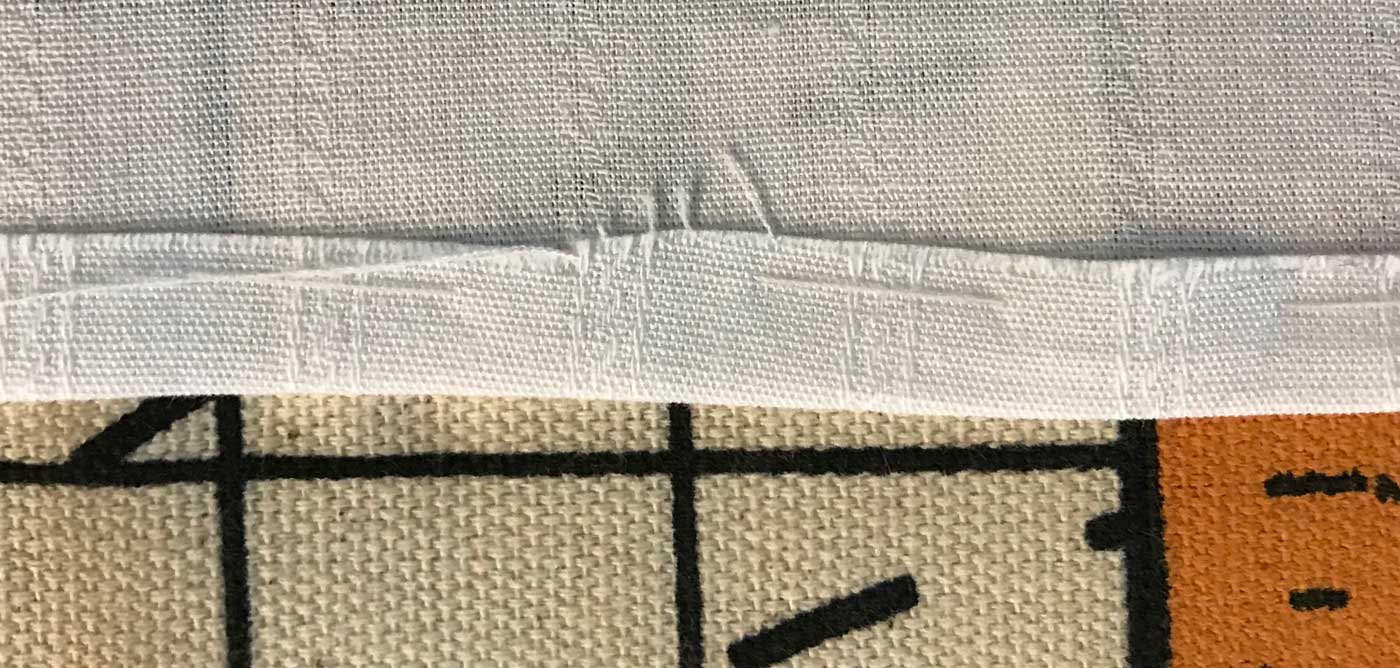

Hemming the bottom hem of the dress.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s collections include garments for men, women, and children dating mainly from ca. 1725 to 1840. Costumes in the Art Museums are typically displayed with appropriate undergarments, wigs, and accessories to provide guests as much historical context as possible. When an ensemble cannot be completed with original objects from the Colonial Williamsburg collections, reproductions are made.

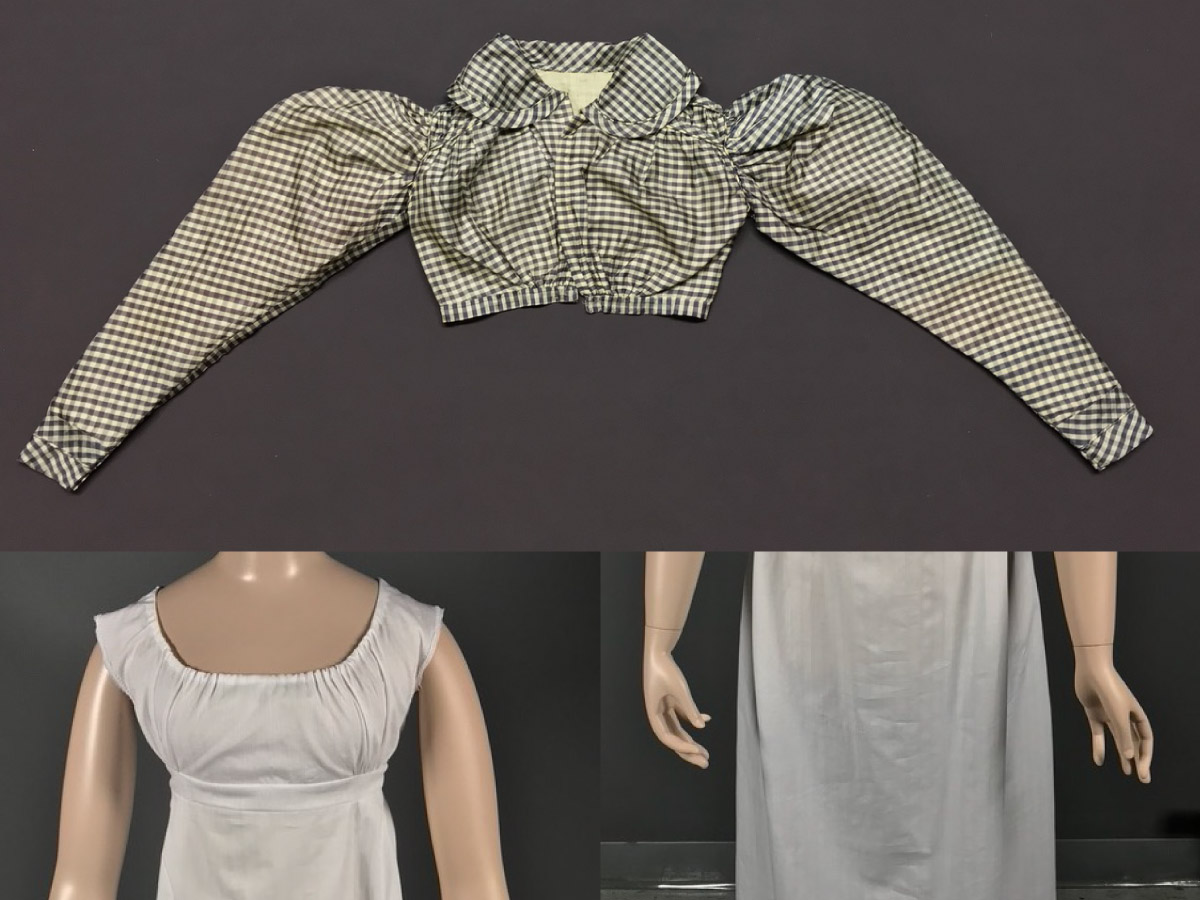

As a graduate intern in the textile conservation lab this year, I had the opportunity to fabricate a dress to be displayed with a ca. 1825 purple and cream checked silk spencer jacket. The jacket is part of a collection owned and generously loaned to Colonial Williamsburg by Mary D. Doering, a costume historian, curator, lecturer, and collector.

Popular in the Regency period (ca. 1810–1825), spencers were short jackets, ending somewhere between the under bust to the waist, depending on the style. They were worn over empire, or neoclassical, style gowns which had fitted bodices ending under the bust and long, loosely fitting skirts which skimmed the body.

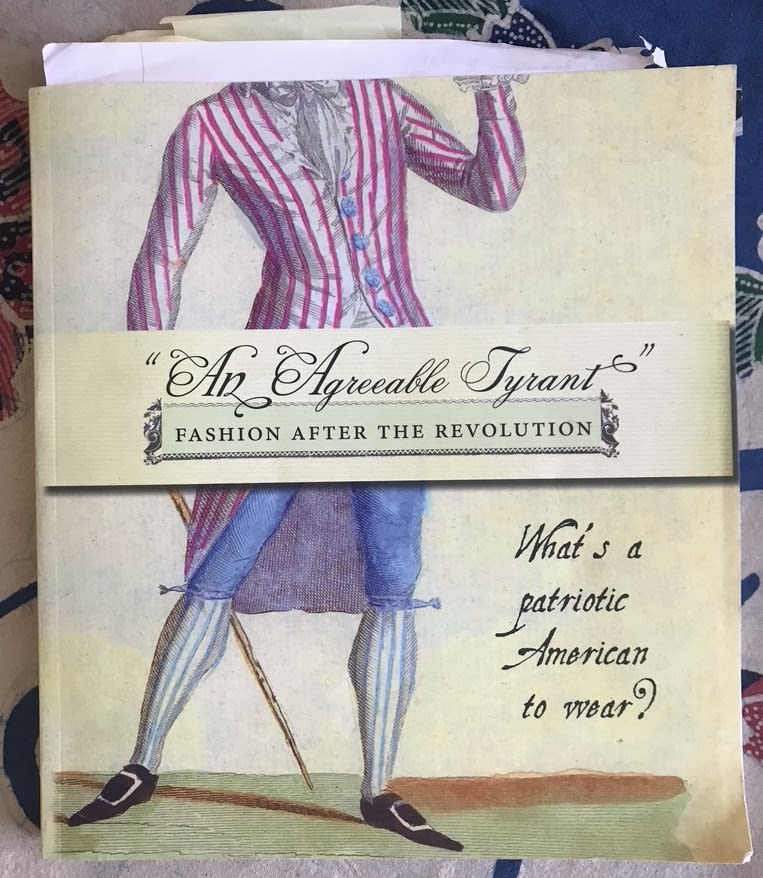

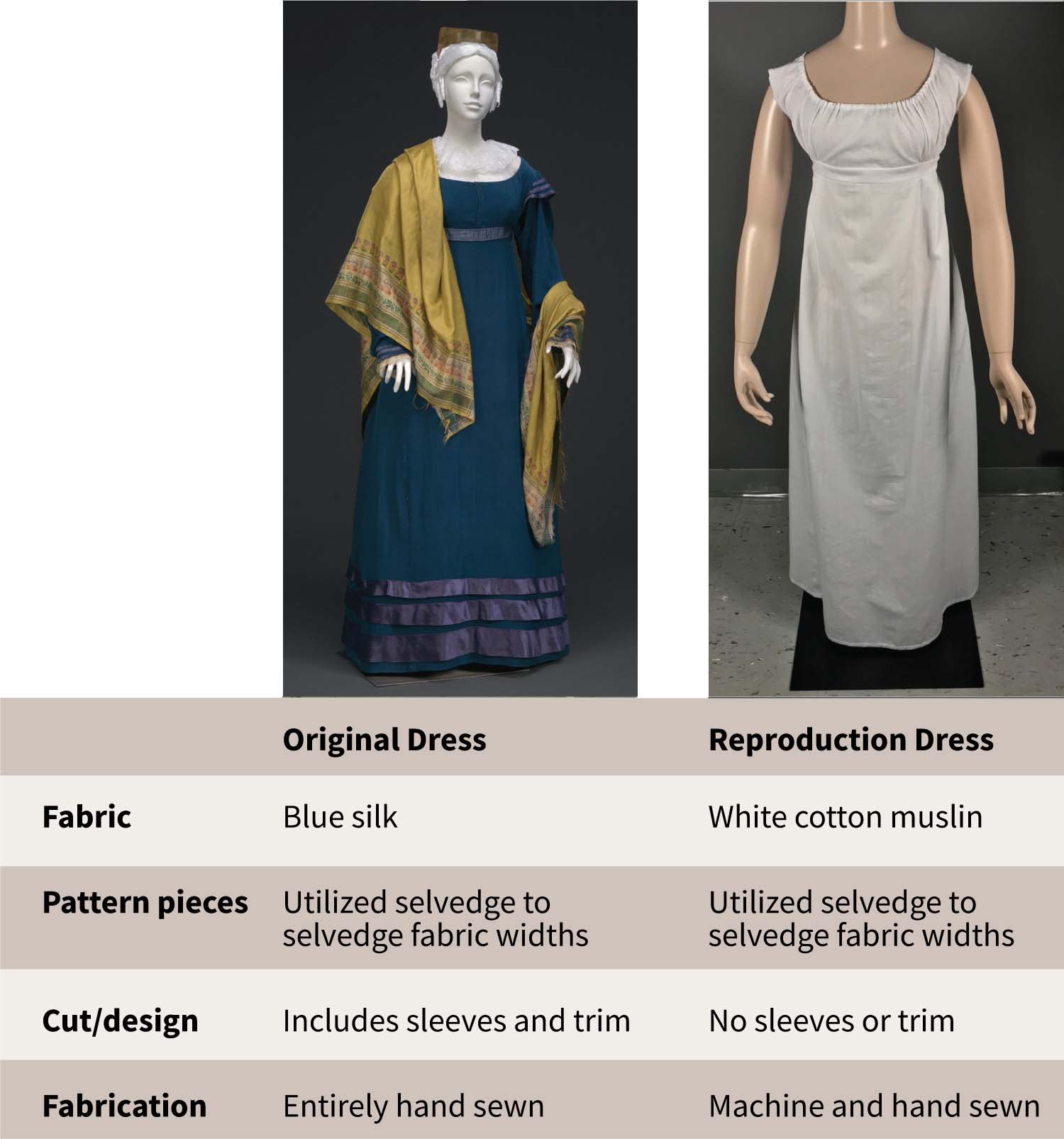

Neal Hurst, Colonial Williamsburg’s Associate Curator of Costume and Textiles, selected a ca. 1815–1820 dress pattern from the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum exhibition catalogue “An Agreeable Tyrant”: Fashion After the Revolution. For the reproduction dress, Neal chose a white cotton muslin with subtle white vertical striping, which is period appropriate but won’t draw focus away from the spencer jacket as a colorful patterned fabric might.

Using the ca. 1820 dress pattern to cut out the white cotton muslin pattern pieces.

The extant garment from which the pattern was drafted has four pieces making up the skirt (front, back, two side gores), three pieces for the bodice (front, two back), and one piece for the waistband. The pattern pieces from the catalogue were scaled up, drafted onto tracing paper, and cut out to serve as the templates to mark and cut the muslin fabric. As the top portion of the dress will be covered by the spencer jacket, it was decided to not take the time to fabricate the dress sleeves, though these can be made and added later if needed for another exhibition. Whereas the original garments from this period would have been hand sewn, reproductions in the lab are made using a combination of machine and hand sewing. Seams which don’t show visible stitching when on display, such as side seams, are typically machine sewn for the sake of time. Areas that are visible or potentially visible, as along the bottom hem, are hand sewn so they have a period correct appearance.

After the fabric pattern pieces were cut out, the raw edges were secured. As part of the seam allowance, the edges won’t be seen, so they were secured using a machine-made zigzag stitch to prevent fraying. This important step makes it possible to use the final reproduction dress in multiple future displays and to wash it if needed.

The reproduction dress was then assembled. The four skirt pieces were joined first, followed by seaming together the bodice pieces, one front and two back. The top of the skirt and the bottom of the bodice were gathered using running stitches. Next, the skirt and bodice were joined to the waistband using hand stitching, with each individual gather picked up and secured using a felling, or whip, stitch. This gives the skirt gathers a lot of shape and volume.

The neckline is finished by folding over the edge twice, inserting two drawstring and tie closures, one at the front and one at the back, and securing the casing with running stitches.

Hemming the bottom hem of the dress.

The skirt was hemmed by first running a basting stitch approximately 1/4" from the bottom edge and then folding the edge up 3/8" and pressing it well with an iron. The bottom edge is then folded once more and felled into place. The final edge, as can be seen from the front in the lower image below, is then pressed well again.

The following is a quick comparison between the original dress and its reproduction:

Without distracting from the original object, the reproduction dress provides physical support for the spencer jacket and allows visitors to understand how it was worn during the early 1800s. It should be noted that the dress and spencer jacket in the images above were mounted to confirm their fit to each other, but the accompanying undergarments typical of the period, such as a corded petticoat, and the carefully contoured padding that will be added to the mannequin to support the garment when on display, are not present. Making these undergarments is the next step in the process of preparing the checked spencer jacket for exhibition.

Come see the spencer jacket displayed with the reproduction dress in the upcoming exhibition Elegance, Taste, and Style: The Mary D. Doering Fashion Collection in the new Mary and Clint Gilliland Costume Gallery in 2022. Textiles funded by Ellan and Charles Spring.

Heather Hodge was a third-year graduate fellow in the Garman Art Conservation Department at SUNY Buffalo State where she specialized in textile conservation. Heather recently finished a yearlong internship in the Textile Conservation Lab.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.