For much of the civil rights era in America — through Supreme Court decisions, acts of civil disobedience and landmark legislation — Williamsburg's First Baptist Church bell tower has been silent. The bell at the home of one of the nation's oldest black churches hasn't rung at times when such a symbol of freedom might punctuate a celebration of equality — and hope.

"The bell has remained silent since the 1950s. We feel like maybe if we could ring that bell…" said the church's pastor, the Rev. Reginald F. Davis, his voice trailing away, leaving the rest of the sentence unfinished.

It is that sense of the unfinished that drives a desire to start a dialogue on race in America and to put the church's bell directly in the center of the endeavor.

That effort — to make the bell ring during the entire month of February — has become something of a mission for a congregation that is celebrating its 240th birthday in 2016. "Let Freedom Ring — A Call to Heal a Nation" is an invitation to all Americans to ring First Baptist Church's bell at a time when racial division is a prevalent part of our national conversation.

Davis sees it as a chance to begin to find common ground in a time when long-simmering misunderstandings have sometimes led to violent confrontation. The congregation was moved to hold a memorial service last June after nine people were shot to death during a prayer service in a black church in Charleston, S.C., allegedly by a 21-year-old white man who now faces federal hate-crime charges.

"We needed to say something," Davis said. "It happened in a church. When one community hurts, we all hurt."

Now First Baptist hopes to capture the nation's attention by ringing a bell whose peals were silenced by 20th-century structural problems. With the help of consultants and conservationists from The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the church's bell was cleaned and stabilized so that it can be used again.

"We ring the bell to commemorate, to remember, to announce," said Jody Allen, a visiting assistant professor of history at the College of William & Mary who has helped to plan the bell-ringing project. "It's a key symbol."

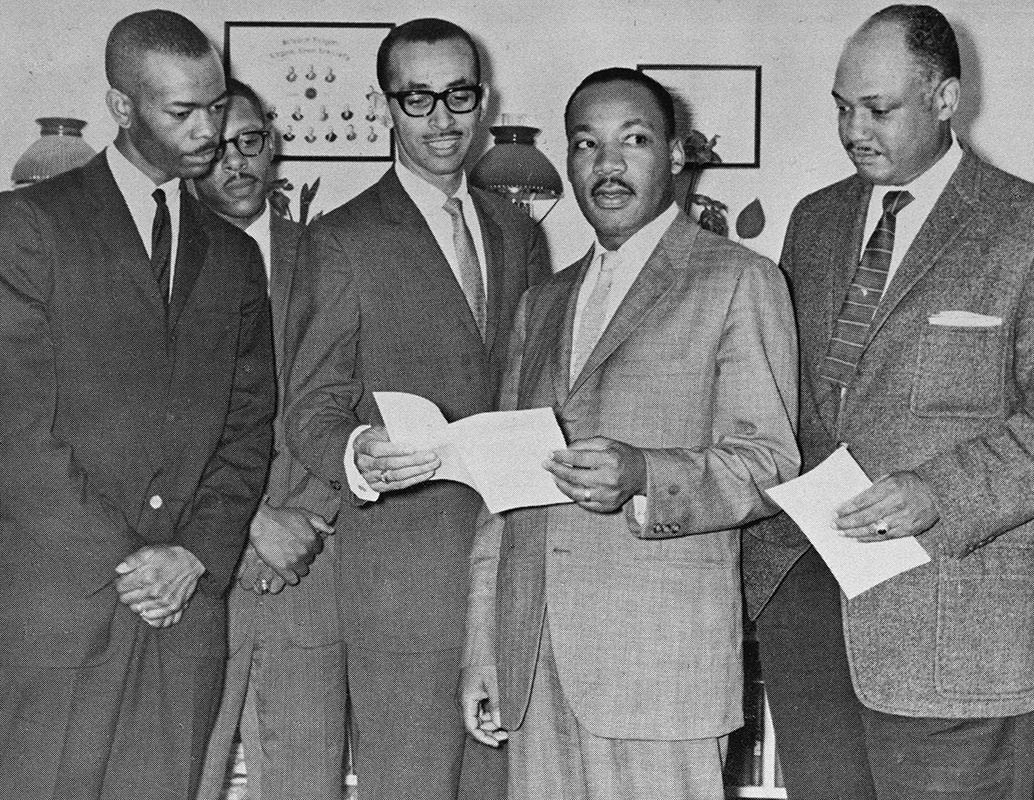

"Bells call people to faith. They send folks forth to do good work in the world," Davis said. "But Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who prayed in our church, also said that freedom rings. A silent bell represents unfinished work of freedom and equality."

Formed in 1776, First Baptist was organized by black preachers for black worshippers. Gathering in secret at first — sheltered by a brush arbor — the group began to worship in a donated carriage house in Williamsburg in the early 19th century. In 1865, the congregation moved into the Nassau Street brick structure that was its home for a century. First Baptist moved to its current location on Scotland Street in 1956.

In fact, American independence is only one moment in which there's an intersection between America's story and that of First Baptist Church.

In the 1880s, the Women's Auxiliary at the church raised the money for several items at the brick church on Nassau Street, including the bell. Its installation came in a small wedge of time between the hope of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the 1865 ratification of the 14th Amendment, and the reality of Supreme Court's 1896 ruling that that declared separate but equal as the law of the land.

And as the fight for equality entered the 20th century in the era of civil rights protests and the Voting Rights Act, the bell was largely silent.

"By the 1880s, African Americans in Virginia and elsewhere faced an increasingly hostile society that sought to undo the political and legal gains of Reconstruction," said Ted Maris-Wolf, Colonial Williamsburg's vice president of Research and Historical Interpretation. "This bell is there — and you can imagine it being rung. They're claiming their freedom and citizenship at a moment when both were rapidly eroding."

There are other pivotal moments you can imagine the bell ringing, Maris-Wolf noted. The end of World War I and World War II, for example. The bell likely did not ring at other significant times for the church, either. The Brown vs. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954 that declared segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional. The publication of King's letter from the Birmingham jail or the March on Washington, culminating with the "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963. Or the signing a year later of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin.

"The meaning of this bell is a dream deferred," Maris-Wolf said.

An important part of the church's story — and one that the bell can help tell — is of resilience and perseverance, said Stephen Seals, the program development manager for African American programming at Colonial Williamsburg.

"The names changed and the buildings changed, but what didn't change was the drive," said Seals, a leading member of the bell-project committee.

That effort can include the sometimes difficult conversation about the role of slavery in that story. Dennis Gardner, a member of First Baptist Church who grew up in Williamsburg during the 1950s, called it a wonderful opportunity to talk about the church, which was birthed by people who believed in their right to practice religion at a time when freedom of all kinds was denied to them.

"We want people to understand the significance of the bell to freedom and what this symbolizes, the church's longevity. The knowledge of what they were up against," said Allen, a co-chair of the Lemon Project, which encourages study and re-examination of the 300-year relationship between African Americans and William & Mary. "They persevered and the story has come down through the generations. We want people to understand and revere the people who came before them.

"So often you don't have that kind of memory. People want to forget for whatever reason. This is a unique opportunity, especially in the African American community. They come and do this and start to think about their own family history and their own church history," she said.

We should place a higher value on perseverance, Allen said. "These were really tough people, strong people who had a vision that was passed down through the years."

There are intensely personal reasons for ringing the bell. To signal hope. To call for open and frank conversations about what divides us as a nation. To come to a reckoning for misunderstandings and even ignorance. To heal.

"I'm happy to see it return," Gardner said. His childhood memories include standing in the Nassau Street church's vestibule, pulling the rope to ring the bell. Children considered it a privilege, he said.

First Baptist Church members hope that embracing the responsibility that goes with that privilege will be part of what could become a movement for a change of heart.

"It's got to start somewhere," said Nat Brown, who is directing external communications for First Baptist. "What better place than a church?"