When visiting Colonial Williamsburg, we hope that guests feel they have taken a step back in time. One way to accomplish this is visually, by dressing our interpreters in historical clothing. It is one of many tools our interpreters use to convey the impression of time travel. The garments seen around the Historic Area are well researched by our Costume Design Center (CDC).

As researchers we study surviving clothing, written documentation such as shipping logs, runaway ads, ads for shops, and portraiture in order to replicate these garments. Hopefully, there is more than one example to study so that we are able to study multiple sources to re-create a garment as accurately as possible. Sometimes we make changes when re-creating garments based on originals. Scarcity of accurate material, the changing shape of the body, production time, and comfort all factor in the re-creation of functional period-correct garments. This blog aims to provide a few examples of the changes we’ve made in clothing closures in our garment adaptations.

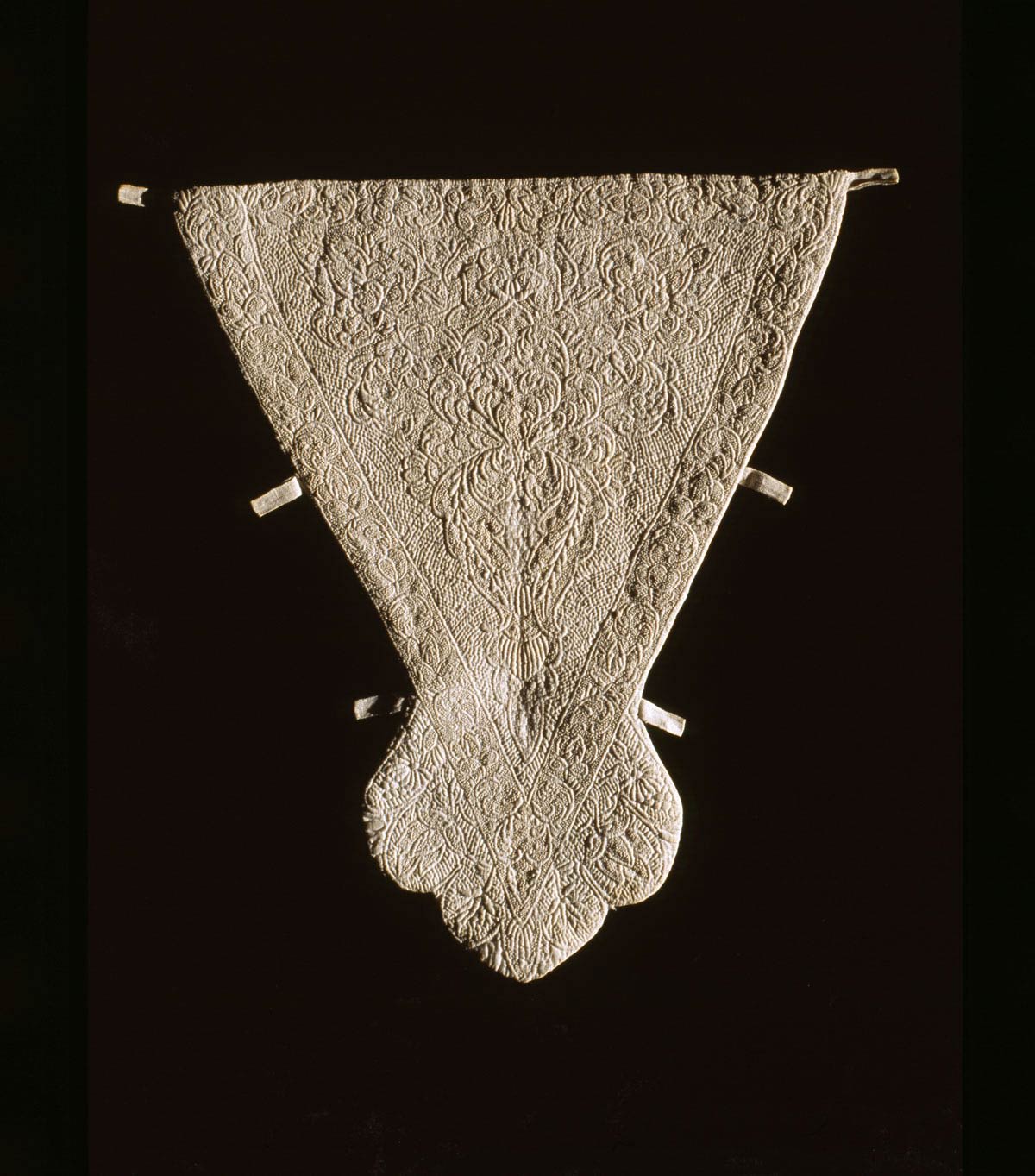

Stays are a foundation garment closed by a spiral lacing and a series of offset eyelets. They mold the body into the preferred fashionable shape of a smooth, inverted cone. (Baumgarten, Watson, & Carr, 1999) Originally stiffened with whalebone, reed, steel, or in some cases pasteboard, our modern adaptation is stiffened with spring steel boning and imitation whalebone. Manufactured in Germany, imitation whale boning is a plastic alternative to actual baleen and it exhibits similar characteristics. Surviving examples of stays from this period are predominately back lacing. (Baumgarten, Watson, & Carr, 1999)

Our modern adaptation is to make stays that are both front and back lacing. Although it is not impossible to lace yourself into back lacing stays, it is difficult without assistance. The idea is that the back lacing can be left in and the wearer can easily lace themselves with the front lacing. Although there is evidence of front lacing stays made in the 18th century, there are few surviving examples. At the CDC we use front and back lacings in a quantity that was probably not seen during the period. (Rosseau, 2020)

Another example of a deviation from an original design is a gown with a stomacher. In the period, straight pins, similar to those we use today for sewing, were used to hold the stomacher in place. Stomachers were decorative panels on the front of some gowns and were usually pinned in place directly to the stays by fabric tabs, then the gown was pinned to the stomacher under a part of the gown’s front opening called the robings. (Waugh, 1968). Evidence of pinholes is seen in both gowns and stomachers on extant garments.

Pins used in the 18th century were usually made using two pieces of brass wire, one piece to act as the shank and the other wound into a coil to act as the pinhead. (Beaudry, 2006) Pin manufacturing was used as an example of division of labor in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. (Smith, 1776) Smith theorized that a shop consisting of ten workers could manufacture 48,000 pins in one day. Because pins were mass-produced, they were plentiful and relatively inexpensive. The CDC’s adaptation for the gown is to permanently sew one side of the stomacher to the gown front and use a row of modern steel hooks and thread eyes on the other to close the gown. These adaptations were made for ease of dressing oneself. Using straight pins in one’s garments is foreign to contemporary experience and the potential for harming oneself with a pin tip can be unnerving. The added expense of providing period-correct pins is not cost-effective. Modern mass-produced pins are structurally and visually different from their 18th-century counterparts. Sourcing a functional, cost-effective, period-correct pin has proven difficult. Finally, the adaptation of hooks and thread eyes extends the life of the garment. As seen on the original stomacher, pins can mar the fabric, multiple pin holes over a small area over time can damage the garment.

The last example I would like to point out today is the adaptation made to our caraco jackets. These are garments require few changes to the closures. The caraco in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection has a false, or sewn-in, stomacher fastened at center-front with metal hooks and eyes. (Caraco Jacket, 2020) As with pins, metal hooks were manufactured in the period and were readily available. (Beaudry, 2006) The CDC reproduction uses modern steel hooks and thread eyes.

The CDC works diligently to create accurate reproductions of historical clothing. In all cases, we want to preserve the original look of a garment as much as possible. When we do make alterations from the original, we strive to keep changes to a minimum and use the most historically accurate methods and materials that are available. With continuing study, new information is always being generated, and we always endeavor to keep current with research. Dressing all our interpreters from head-to-toe in all seasons is quite the task, but one we are committed to so that we can present as accurate a representation as possible of the people who lived here.

Aileen Krotz is a Tailor A at the Costume Design Center. She has worked in the museum field for over ten years. She enjoys making historical clothing for herself and others, attending reenactments, and making socks on a circular sock knitting machine. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in history from The College of Staten Island.

Resources

Baumgarten, L., Watson, J., & Carr, F. (1999). Costume Close-Up. Williamsburg, Virginia: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Beaudry, M. C. (2006). findings: the material culture of needlework and sewing. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Caraco Jacket. (2020, December 16). Retrieved from Colonial Williamsburg: https://emuseum.history.org/objects/9849/jacket-caraco?ctx=90e40acc613b7fcd5f5be2718bac497a36d961d1&idx=0

Rosseau, B. (2020, December 4). Costume Design Manager. (A. Krotz, Interviewer)

Smith, A. (1776). The Wealth of Nations.

Waugh, N. (1968). The Cut of Women's Clothes 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.