Over the last few months, the archaeology crew has been hard at work at Custis Square, finding cool artifacts researching the unusual sources of the medical remedies that John Custis recorded in his commonplace book, and mapping where Custis’ household goods ended up after his death. One of our most intriguing finds, though, was not at Custis Square. Instead, it was right across the street!

Last fall, we began initial archaeological excavations at the site where the First Baptist Church stood in the 19th century. While working on that project, we came across a pit in the ground filled with wine bottles, ceramic sherds, and animal bones in the early 18th century — almost 100 years before the construction of the church, when the property was owned by John Custis IV.

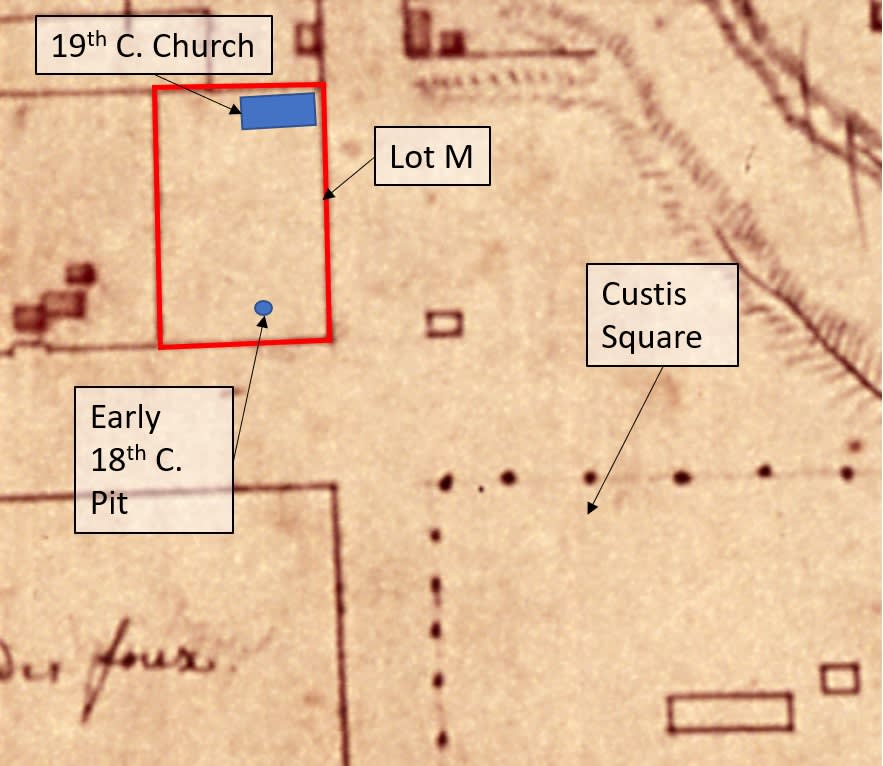

The pit is located along the southern edge of the half-acre lot known historically as Lot M. It was first identified when archaeologists from Jamestown Rediscovery completed a ground-penetrating radar survey of the area hoping to identify buried foundations. The radar images showed a large, fuzzy blob, indicating that, at some point in the past, the natural soil layers in this area were disturbed, most likely by someone who dug a large hole that was later filled in again. In October, we excavated a small test excavation in the area and confirmed that it was indeed a large pit, but we were surprised to find that it was filled with early 18th-century artifacts. Since the purpose of the survey was to investigate the 19th-century church, we did not explore the feature any further at that time. In November and December, there was a short gap between the first and second phases of the First Baptist Church excavation. We took advantage of the time to excavate the pit feature to see if we could get an idea of what its purpose was and, hopefully, a better understanding of what was happening on Lot M in the early 1700s.

When Custis decided to move to Williamsburg around 1715, he bought a whole block of eight half-acre lots to build his estate on (known today as Custis Square), along with several of the surrounding lots as well. He purchased Lot M, the property just NW of Custis Square, in either 1717 or 1718 from William Blaikey. We know, based on the surviving record of this sale, that Blaikey had purchased Lot M, and a house that stood on it the previous year from a man named John Tullitt, a local brickmaker. However, we don’t have any documents that tell us what Custis did with the property after he purchased it. This pit and the artifacts it contains are the only clues that we have to tell us what happened on Lot M during John Custis’ lifetime.

As we dug into the pit, we found over a dozen wine bottles which had broken when they were thrown into the pit. All the wine bottles have a squat, bulbous shape which was common in the early 18th century. Additionally, we found a single wine bottle seal, marked “John Custis” that had had broken off the wine bottle it was originally attached to. Bottles with the same seal were found in the bottom of a well at Custis Square during the 1960s excavations. While wine bottles were very common in early 18th century Williamsburg, the Custis seal found in the Lot M pit proves that there was some connection between this pit and the activities and people at Custis Square. The animal bones we found in the pit are large and appear to mostly be from pigs and cows — probably scraps left from the butchering of animals for food. We also found several large pieces of “colonoware” bowls. These types of ceramic vessels were made by local potters in the early 18th century and were both cheap and easily available. Although colonoware bowls were used by many of Williamsburg’s 18th-century residents, this type of ceramic is most often associated with enslaved Africans and African Americans. Could these bowls have been used by the enslaved families at Custis Square? As we wash, process, and analyze the artifacts that we found during this excavation, we can begin to answer this question and more. Stay tuned as we learn more about the Lot M pit feature and what it can tell us about the people living at Custis Square!

Eric Schweickart is a Staff Archaeologist with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Eric has an MA in Historical Archaeology from the University of Leicester and a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His research focuses on consumerism and household economics in the North Atlantic in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Eric has excavated archaeological sites across the southeastern U.S. over the last decade, including Sapelo Island, Georgia, the Montpelier Plantation in the Virginia Piedmont, and the Coan Hall site on the Northern Neck of Virginia.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.