Exploring a Carpenter’s trade through the Revolutionary Chesapeake

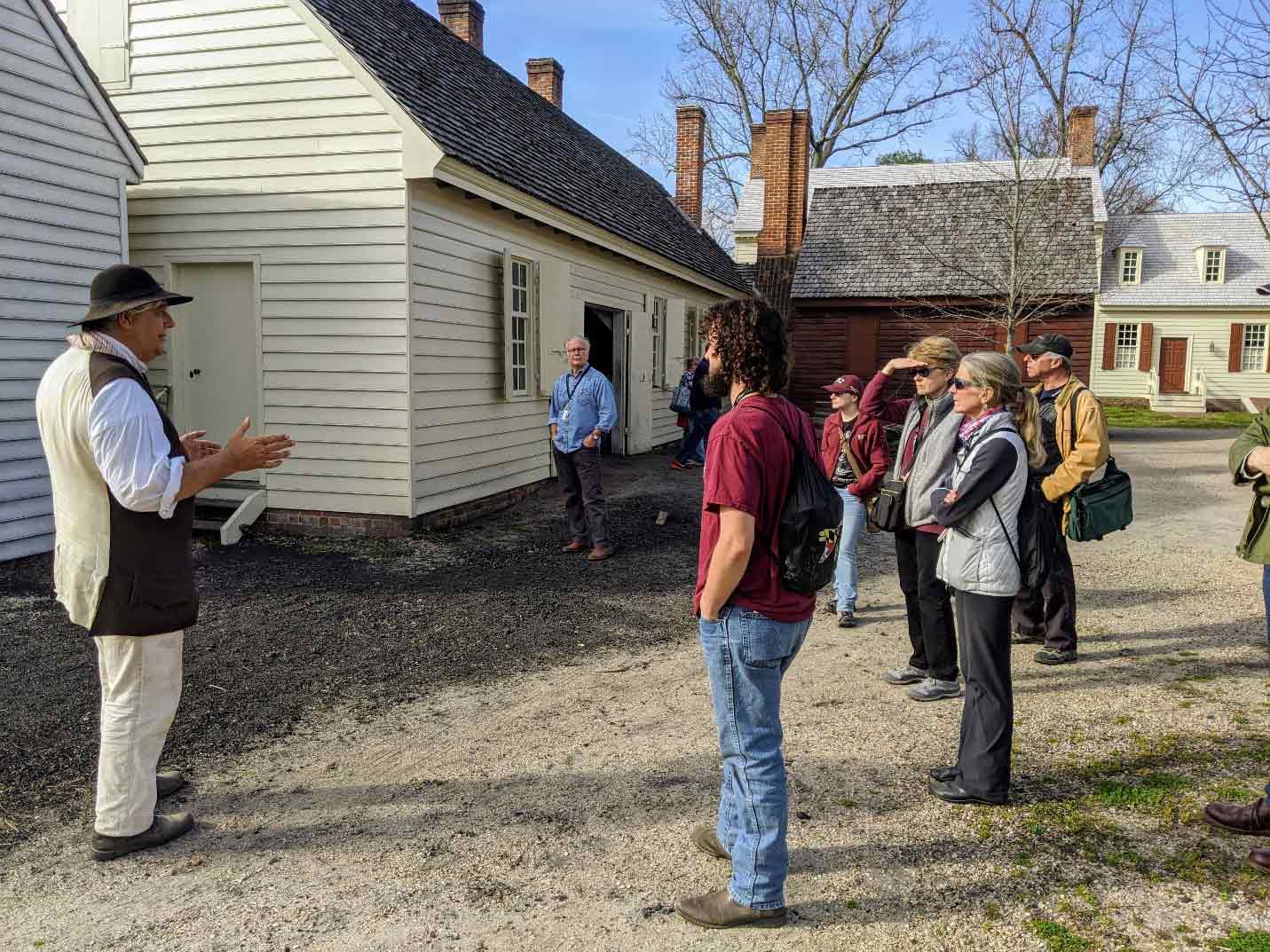

Carpentry was one of the many highlighted historic trades in Washington College’s recent Revolutionary Chesapeake program, offering participants the opportunity to engage with Colonial Williamsburg’s historic carpenters in discussions surrounding the theory and practice of their trade. Participants also received hands-on instruction in some of the many skills required of the trade while exploring the Carpentry’s significant role in the American Revolution.

Carpenters in Williamsburg and throughout the Chesapeake Bay region provided essential services to the Revolutionary cause through the construction and repair of public buildings such as hospitals, barracks, stables, storehouses, and workshops. Skilled tradespeople, either free, enslaved, or coerced, capable of swinging an axe, leveraging a froe, wielding a drawknife, or operating the numerous varieties of saws, helped to underpin America’s Independence movement.

Some of these skills were attempted by the Revolutionary Chesapeake participants, helping them to gain empathy and insight into the complex lives of those Revolutionary carpenters while contemplating the impact of their work.

Splitting and Riving

The group attempted splitting and riving oak logs for clapboard, riving and shaving Juniper for shingles, and pit-sawing pine for lumber.

Clapboard was used historically as a cheap siding and roofing material, and can be seen on several of the reconstructed buildings at the James Anderson Publick Armoury in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Shingles

Pitsawing

A pitsaw allows two carpenters to saw through squared-off logs from top and bottom, following lines “chalked” with charcoal dust, to create board lumber of various dimensions. One carpenter stands on top of the log, while the other stands in a pit dug into the ground. Alternatively, historic carpenters could also use trestles, instead of a dug pit, a method favored by French carpenters during the 18th century. Several sawpits from the 18th century have been found archaeologically in Williamsburg.

Water-powered sawmills were also producing an incredible amount of lumber during the time of the American Revolution, taking advantage of natural fast-flowing water sources to provide for an expanding market for sawn lumber.

One of the most conspicuous aspects of the Carpenter’s trade is their connection with the regional ecology and available materials of a certain time and area. Several different species of Oak, Cypress, and Pine constitute just some of the historical building materials that were exploited for their unique properties and availability in the Chesapeake region. The variability of tree species and growth, available methods for processing those materials, as well as the aesthetic design choices combined to create unique functional and regional structures, what modern architectural historians define as “vernacular architecture.” This architectural language can be explored in-depth throughout the original and reconstructed buildings at Colonial Williamsburg. The Revolutionary Chesapeake program specifically explored these details at the James Anderson Publick Armoury with Master Carpenter Garland Wood and in discussions with Master Blacksmith, Ken Schwarz.

Architectural design, building materials, and construction techniques all feature in the study, preservation, and reconstruction of historic buildings at Colonial Williamsburg and help to form a more comprehensive history of Chesapeake society during the American Revolution.

If you are hungry for more information on the architectural history of the Chesapeake Bay region, check out Colonial Williamsburg’s Architectural Preservation and Research Department online and, The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg, edited by Cary Carson and Carl R. Lounsbury.

For more information on this course and the collaboration between Washington College and Colonial Williamsburg, visit Washington College’s Center for Environment and Society or you can contact:

- Dr. John Seidel who serves as Director of the Center for Environment & Society and is Lammot du Pont Copeland Associate Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies at Washington College.

- Chuck Fithian, who is a Lecturer in Anthropology at Washington College.

- Joel Anderson, Journeyman Tinsmith, or Rob Welch, Apprentice Shoemaker, who coordinate Washington College’s Colonial Williamsburg experience, and can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively.

Joel Anderson is Journeyman Tinsmith at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, serving within the James Anderson Public Armoury. Joel has been with the foundation since 2013, having recently completed Colonial Williamsburg’s inaugural apprenticeship in historic tinsmithing. Originally from Spartanburg, South Carolina, Joel’s interest in American history started at an early age, and eventually lead him to a career in museums. An avid equestrian and craftsperson, Joel has a deep commitment to horsemanship, historical tailoring and leatherwork.