It’s undeniably the question we get asked more often than any other in the millinery shop: how much clothing did the “average” woman have in the 18th century? On the surface, it seems like it should be an easy inquiry to answer, but its complexities might surprise you.

One of the documents we love to share with visitors is an inventory of the property of a woman named Mary Cooley, which you can view transcribed here as part of Colonial Williamsburg’s free digital library collections. Cooley was a nurse-midwife from York County who passed away in February of 1778; her status as a widowed woman and mother to a minor child necessitated a probate inventory be taken to value her estate. At the time of her death, her wardrobe included 10 gowns, 6 petticoats, 13 aprons, 15 caps, and 9 shifts, among other items. Not bad for a working woman and single mom. But a closer look at the descriptions and values of the garments listed quickly reveals a problem with this data. Clearly, Mrs. Cooley was not delivering babies in damask, crimson satin, or Persian silk, so where are her work clothes? Because inventories represented the official record of a deceased person’s estate, they only included items of sufficient worth to be resold. Pieces with no perceived resale value – like well-worn everyday clothing – went unenumerated and were simply thrown away, leaving us with an incomplete picture of precisely what an individual’s wardrobe looked like. There was always, in short, more than what we’re left with on paper.

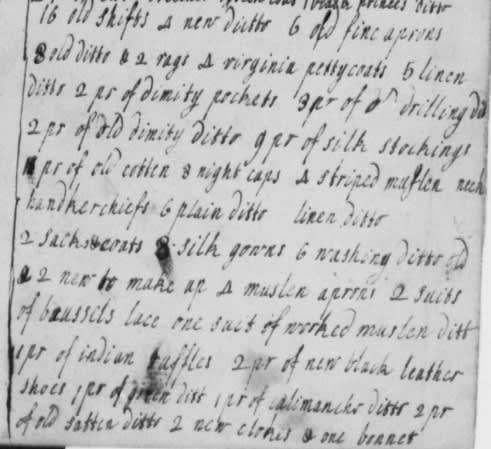

Consider, for example, an inventory by Martha Jefferson, wife of Thomas Jefferson, written several months prior to Mary Cooley’s in September 1777. Taking stock of her own wardrobe, Martha lists 16 gowns (18 if you count the 2 “to be made up”), 9 petticoats, 18 aprons, and 20 shifts. Assuming this personal account is complete (note the number of times she distinguishes “old’ items), the numbers are actually quite comparable to what we might imagine Cooley’s to have been, despite the discrepancy in socio-economic status between the two women.

Header image by Wayne Reynolds

Even these self-reported numbers are problematic, though, when it comes to answering the “how much clothing” question. While we’re fortunate enough to have a document like this, what we lack is its contemporary historical context. What motivated Martha Jefferson to take an inventory like this in the first place? Should it be understood as, “Thomas, I only have 16 gowns! I simply must go shopping before the season begins!” Or is it, “I have 16 gowns. Let’s lay off on the spending for a bit, dear”? Was 16 considered a large number? Was Martha Jefferson representative of women of her socio-economic position, or simply representative of all fashionable women who liked to shop, regardless of class?

But didn’t people have to make all their own clothes?

Most people knew how to sew in the 18th century. As a basic life skill, sewing was taught to boys and girls from all levels of society as part of their practical education. But knowing how to sew didn’t mean that everyone knew how to make clothing. As we like to say in our shop, knowing how to hammer in a nail doesn’t mean you can build a house. Cutting out the shapes for garments and fitting them to a unique body was something an individual had to be trained to do through a formal apprenticeship. Before patterns, instruction books, and the internet democratized that knowledge by making it easily accessible, only professionals had the full range and depth of skill necessary to produce clothing. While sewing did happen at home, it was the kind of sewing that mended and maintained a wardrobe, rather than the sewing that manufactured it from start to finish.

But most people didn’t have a lot of money back then, so how could they afford custom-made clothing? Wasn’t that prohibitively expensive?

While it is true that access to currency in the form of cash in the colonies was limited, that didn’t stop people from spending! Think about how the economy works today: most of us don’t carry cash, either. Instead, we rely heavily on credit, a stand-in for money that represents the promise of future repayment. The same has been true for 300 years. Eighteenth-century Virginia was an agrarian economy, meaning that most people had cash in hand once a year when their crops were harvested and sold. To keep the economy going in the meantime, merchants and shops maintained credit account books that permitted customers to spend freely — whether they had the funds to back that spending or not. Some things never change!

Keep in mind, too, that just because a person may not have a considerable budget to spend on clothing, it doesn’t necessarily follow that he or she has to have a small wardrobe. Just like today, clothing was available at a wide range of price points. Because it was the cost of materials — and not the price of labor — that dictated the value of most goods, consumers simply chose less expensive fabrics to get more affordable garments. The season’s most fashionable style could be cut just as easily in a workaday worsted wool as in a luxury silk brocade. Given the choice, would you rather spend $150 on one name-brand pair of shoes, or the same amount on three $50 pairs of shoes without the designer label? For some people, “fashion” is in the status of the brand, while for others, variety of ensembles is more important. The way a person chooses to dress — both in the 18th century and today — tells us much more about his or her priorities and interests as an individual than it does about his or her social status or income level.

But I know for a fact that closets were quite small and houses in the past didn’t have many of them, if they had them at all. Doesn’t that imply that people couldn’t have had as much clothing?

True! The lack of closet space is a frequent and accurate observation made by visitors to our historic houses here at CW. But closets in the 18th century were used for very different things than we tend to use them for today. An 18th-century closet could be locked, making it the ideal place to store valuable portable property, like the family’s silver. Clothing was stored instead in furniture pieces like chests of drawers and clothes presses, or in portable storage like trunks, making it easy to set aside off-season or occasional pieces until they were needed again. When actively being worn and circulated within the wardrobe, clothing could be kept readily accessible on pegs to air out and to help prevent wrinkles.

But that brings us full circle! How much can you really fit in just a chest of drawers? It can’t be much at all…

We wondered about that, too! Being the experimental and experiential historians that we are, we in the millinery shop decided to put this quandary to the test using Mary Cooley’s inventory. This year’s woodworker’s symposium back in January focused on — you guessed it! — a chest of drawers, so we seized the serendipitous opportunity to put together a program for some of the attendees that put the chest’s true volume to test.

To our own and our attendees’ surprise, what we discovered was that a four-drawer chest could comfortably accommodate not only the entirety of Mary Cooley’s inventory as recorded, but a number of additional pieces as well. In the interest of representing a working woman’s wardrobe as accurately as possible, we added to the pile two flannel waistcoats, three underpetticoats (two linen and one wool flannel), two bedgowns (semi-fitted jackets for working wear), and two extra “washing” linen gowns appropriate to her profession as a nurse-midwife. The entire wardrobe fit beautifully! We like to think that the “chest” that’s also listed on the inventory was once used in very much the same way, helping to keep a working woman’s everyday wardrobe neat and organized and ready to wear.

Apprentice milliner and mantua-maker Rebecca Starkins joined the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 2016. Her research interests include puzzling out the intricacies of outerwear styles and examining representations of working women in 18th- and 19th- century literature by female writers.