It’s a known fact that our interpreters have many different skills. We, at any one time, may need to not only be an historian but also a writer, director, researcher, host (or hostess), costumer, psychologist, psychoanalyst… and that’s just on a Tuesday. Another area that our interpreters also dive into in order to fully immerse themselves in the 18th century is understanding and learning the various skills and pastimes that the people we portray enjoyed. Along those lines, several of us have found a true love of both teaching and researching hobbies that our Founders participated in. Robert Weathers and I have been involved in one such pursuit for the better part of a decade. Not only do we work together during the day, bringing to life George Wythe and Martha Washington in the Nation Builder unit, but we also work together at night as the Creative Leads of the Evening Dance Ensemble.

Our ensemble performs for school groups and the general public all over the Historic Area teaching guests and students alike about the various forms of dancing that were popular during the 18th century. One of the main interpretive points we try and make in each program is that dancing was a social event but primarily learned at home. Since many of us are at home right now, Robert and I thought to give a little virtual dance lesson so that you might have the chance to learn a new pastime from the comfort of your living room!

First things first…the history part…there were several different styles of dancing that were popular during the time that we study and interpret. The most popular styles being the minuet, country dances, and cotillions. Let’s discuss those three briefly.

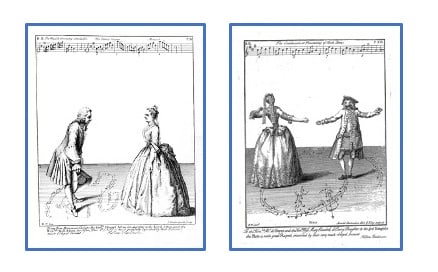

The Minuet was developed at the court of Louis XIV of France in the late 17th-century and was considered a “dance of ceremony". By the mid-18th century, it was being stepped at the beginning of balls and assemblies in England and in America as a way to highlight your dance ability and skills (read: to show off). It was stepped from the highest-ranking couple in the room to the lowest ranking, in a distinct step that required skill and balance. It was danced in silence, which meant that the man led the dance by signaling his partner with arm movements and the management of his hat. This created an intense concentration and eye contact between the dancers that sometimes had the minuet being described as “tracing the figures of love.”

The minuet was not one particular dance, but a dance form. While most minuets were made up spontaneously on the dance floor by following some basic conventions, the common minuet, or menuet ordinaire, was a standard routine that any two dancers could safely perform without previous practice together. There was also the menuet figure, or an ornamented form, where two dancers could really display their skills. The minuet stayed popular at English assemblies well into the mid-1760s and American balls through the American Revolution.

After the minuets were stepped for the evening, the real fun could begin. Country Dances were the bread and butter of dancing in 18th century England and America. The figures for over 25,000 dances were published with their music in English books between 1700 and 1830. The first, and most noteworthy, publication of these country dances came from John Playford’s work The English Dancing Master, first published in 1651. Typically danced for “as many couples as will,” or as many couples as could fit on the floor, these dances were noted for their up-tempo music, accessibility, and social nature.

In fact, many of our Fife and Drum tunes are country dances as they were considered “popular music” for the soldiers to listen and march to. The basic format of a country dance is for couples to create long lines down the dance floor with the men on one side and the ladies on the other. Danced with two or three couples at a time, the couples then progress to a new set of couples with each turn of the dance, moving all the way down the line and back up, essentially dancing with every couple on the floor, twice. Speaking from experience, these dances are a lot of fun and we’ve yet to meet a guest who can’t step a country dance after learning the basic figures. These are not meant to be difficult, and we often say to our guests who join us, “If you can walk, you can dance!”

The last form of dance that we will discuss here is the Cotillion. My personal favorite style of dance, the Cotillion came to America in the 1770s by way of France. Rather than being danced in long lines with men on one side, ladies on the other for as many couples as will (say that 3 times fast), Cotillions are stepped in a square with four couples at a time…yes, this is the great-grandfather of the modern square dance. The Cotillion also has a different format than the country dances, in that it there are teo distinct portions of the dance, the “figure” and the “change.” It works much like a song: the figure is a set of movements that repeat over and over throughout the dance, much like the chorus of a song while the changes punctuate between them and act like the verses. So, the format goes: change, figure, change, figure, change, figure…with a different change each time. This dance is beautiful to watch and really encourages the dancers to work together.

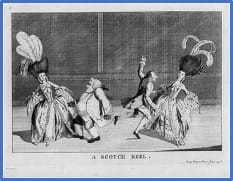

There are more dance styles including Hornpipes, Jigs, Reels, Allemandes, Rigadoons, and Gavottes, but for this post, we’ll just focus on those main three. Although we couldn’t pass up showing you this image of a Scotch Reel below…

Where did a student typically begin? Well, we are going to take you, dear reader, through the same paces that an 18th-century dancing student would. The first lesson is to learn your proper honors … stay tuned for our next installment!

Come dance with us when we re-open!

Dancing at the Governor’s Palace is offered every Monday evening at 7:30pm. Join our dance ensemble for a lively family-friendly evening of dance and music in the Palace Ballroom. We’ll demonstrate various dances of the 18th century and then invite guests of all ages to join in on the fun.

About the Authors

Katharine Pittman is a Nation Builder for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation researching and portraying Martha Washington. Her love of history started young as her parents brought her and her brother to CW with frequency as children, grew while getting her degree from Wake Forest University in history and theatre, and cemented in her almost 9 years with the Foundation. Outside of the 18th century, Katharine enjoys spending time with her family, watching Outlander with her girlfriends and drinking massive quantities of coffee.

Robert Weathers has been working as a first-person interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg since January 2008 and portrays Nation Builder George Wythe. When he is not in breeches, he can often be found wearing shorts no matter the weather, and riding roller coasters with his wife Kaitlyn.

**Special thanks to Colonial Williamsburg historian, Cathy Hellier, for her generosity and assistance with this blog.

Resources

Keller, George Washington: A Biography in Social Dance