The title of this blog alludes to the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky’s influential novel Crime and Punishment published in 1866. Even then, Dostoevsky grappled with issues of guilt, horror, and the consequences of one’s actions. It is not coincidental that this post appears today, December 10th, a day that commemorates the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. Through this blog, like Dostoevsky, we aim to examine the horrors of the past, this time in Williamsburg, and the consequences of those actions today. The discussion is an opportunity to reflect on changes in the museum’s thinking, and how these changes impact the way we tell the stories of 18th-century people and their human rights.

You may have noticed that the stocks, pillories, and whipping post in front of the Courthouse of 1770 on Market Square have been inaccessible for some time. Initially, this was due to constraints that COVID-19 placed upon us for over a year, but also that the structures were coming to the end of their safe, usable life. Additionally, these past few years have provided Colonial Williamsburg, along with many others in our society, opportunities to reconsider how we tell stories of the past. Thus, with an eye to the future, Colonial Williamsburg is reviewing how we can more deeply consider how we interpret this important site.

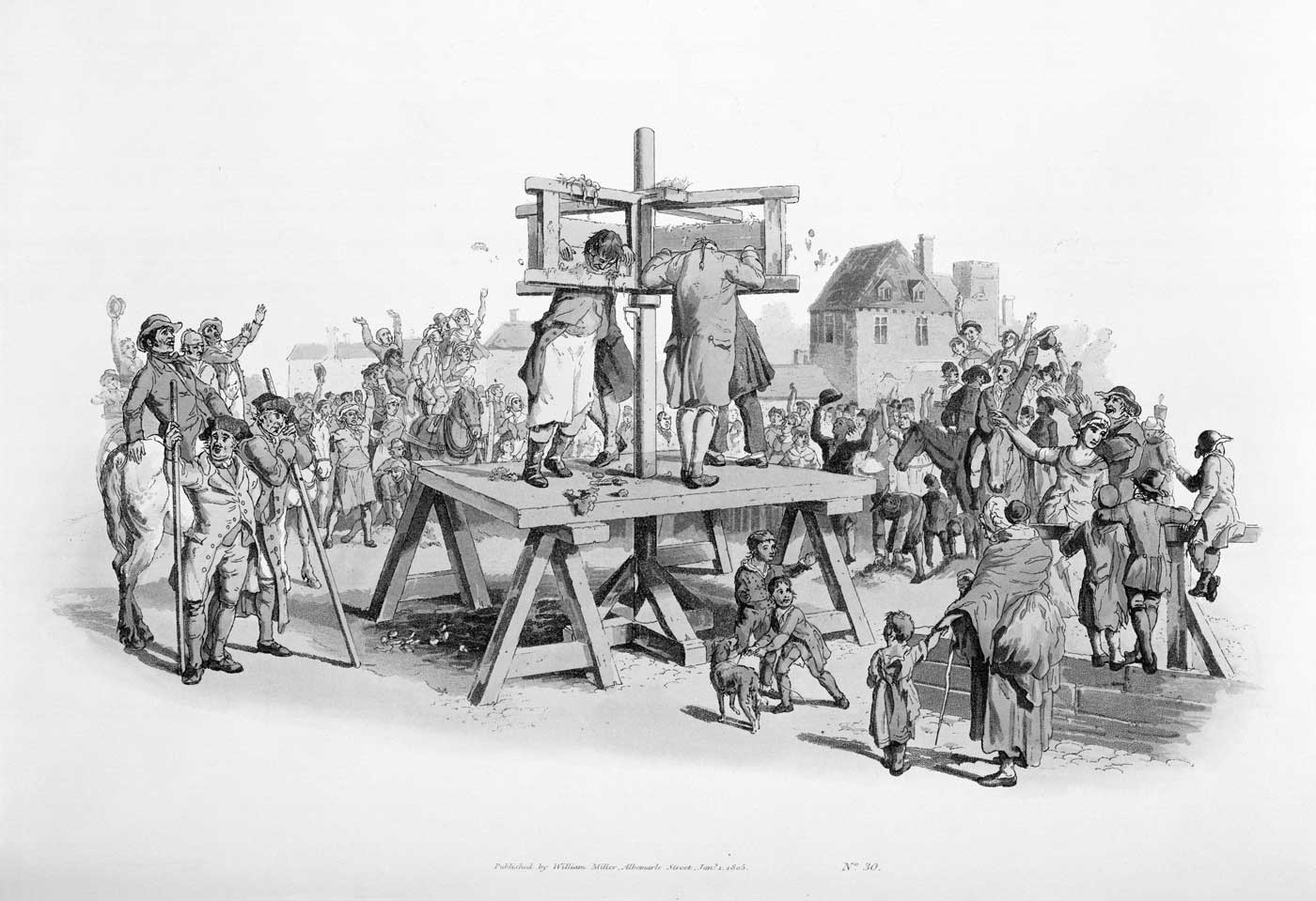

To this end, a broad group of Colonial Williamsburg staff is working together to examine an appropriate way to interpret these devices and seeking to reassess how we tell the story of the location’s 18th-century function as a place of humiliation and, by modern standards, torture.

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that:

“No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

It is inconceivable that nailing people’s ears to the pillory or whipping someone on a post in the center of town would not contravene Article 5 today. These actions are now prohibited by law in America, although we know there are countries who have not signed the Declaration, and still others who continue to use practices such as these. It is from this different way of looking at the site, as a place where individuals were severely punished, that we are rethinking its interpretation.

In 2022, we will embark on a reconsideration of the site and presentation of its history. The story begins with the medieval English origins of these structures, and how they were developed as part of a linked approach to punishment, through physical torture and public humiliation. This practice was codified into law and transferred to the English colonies with the first English settlers arrival in Virginia. While each person was technically equal under law, their experiences were actually very much different, with outcomes being based largely upon social hierarchy and race. This law was also changing. The law had been developed in the context of Great Britain, but the unique circumstances of the American colonies meant the creation of a new legal system to deal with these new conditions. This is most clear in the example of enslavement, where two sets of laws were set in place, the codified “legal” set of rules and punishments, and the “extralegal” set of behaviors that fell outside the regulation of the law. We anticipate that this journey into the experience of crime and punishment in 18th-century Virginia will be enlightening, but it will also be troubling and traumatic.

Along with the historic research currently being undertaken, our Architectural preservation and research team is working to develop plans for building a new set of punishment equipment. These ubiquitous forms of punishment were to be found all over the old and new worlds in the 18th century, but today almost all have rotted into non-existence. Surviving records do provide a source for the location, maintenance, and sometimes even appearance of Virginia examples. These prove very different from the ones originally designed for Colonial Williamsburg’s historic area.

The equipment we have today was designed in the 1930’s and originally set up as an interactive fixture at the Gaol. It is unclear if there ever were stocks and pillories at the Gaol, but we now know that there would have been examples at the Capitol and at the Courthouse. The design team is going back to first principles and completely redesigning the equipment to be as historically accurate as possible. This commitment to accuracy also means that the equipment will not be usable by the public – they were designed as tools of torture, after all. But this does not mean you won’t be able to see them. We will reassess the site and how we interpret it, but with a renewed compassion and honesty partnered with the more accurate reconstructions of the stocks, pillories and whipping post as they would have appeared in the 18th century. The result will not only be an examination of our shared past, but also an exploration of the site’s relevance to today’s America.

As Colonial Williamsburg approaches its 100th anniversary in 2026, we look forward to the future of the museum for the next 100 years. In the recent past, visitors were encouraged to use the stocks and pillories as a photo opportunity. Today, we have suggestions for more appropriate places in the Historic Area to take photos. The site of the reconstructed stocks, pillories and whipping post will thus do better justice to the people who were punished there. It will provide a more accurate and nuanced story of what these pieces of equipment were used for, the trauma they inflicted both physically and socially, and their relevance to understanding of America today. With renewed focus on context, authenticity, and the whole story – this equipment will truly tell a more complete story.

“The man who has a conscience suffers whilst acknowledging his sin. That is his punishment.”

― Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

Dr. Peter Inker is the Director of the Historical Research and Digital History Department. He is passionate about the past and living history museums. Originally from Wales, UK, he now lives permanently in Virginia.

Further Reading

Dostoyevsky Fyodor, 1911. Ernest Rhys (ed) Crime and Punishment. London, New York: Everyman Library

Friedman, Lawrence. Crime And Punishment in American History. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.