The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

In the Summer of 1793, the United States would suffer its first epidemic as a fledgling nation. Certainly, in years previous, there had been occasions of Small Pox and other illnesses including a 1762 outbreak of Yellow Fever, but this would be the first test of the newly formed government’s ability to respond to health emergencies.

That summer in Philadelphia had been unusually hot and humid. The local waterways in America’s largest city had diminished to very low levels. Perfect breeding grounds for mosquitos though their part in this was not yet understood at the time. Several period accounts refer to the huge numbers of flies and mosquitos in the city.

Blamed at the time, and by many historians, thereafter, was the presence of several newly arrived refugees from San Dominique (Haiti). An estimated 2,000 immigrants, mostly white Frenchmen had arrived in the port escaping the slave revolt. Yellow Fever, however, while far more common in the Wes Indies, was not unknown in America. After the 1793 epidemic, Dr. Benjamin Rush would come to the opinion that a handful of earlier epidemics of what had been thought seasonal flus, were, in fact, this dreaded disease.

Today it is understood that the disease is carried by mosquitos, most commonly the Aedes aegypti, a mosquito particularly well adapted to living in urban areas. Philadelphia at the time was the largest city in America with an estimated population of 50,000 people. The illness begins with fevers, chills, loss of appetite, and is easily misdiagnosed as a more benign illness. Often the symptoms will dissipate temporarily, giving the illusion that the patient has recovered, only to return with its harsher attacks upon the liver, kidney, and stomach. Patients become jaundiced and near the end, begin vomiting black.

Beginning with the first identified deaths of an Englishmen and an Irish woman in early August 1793, and by the 25th of that month a full panic had begun. This disease originally ran rampant through the overcrowded and dirty parts of the city around Water Street, but the illness became a great leveler. Mosquitos attack the poor and the rich alike. Even Samuel Powell, a personal friend of George Washington and former mayor of the city lost his life to the disease. Forty percent of Philadelphia’s population would leave, including Secretary Thomas Jefferson and even President Washington.

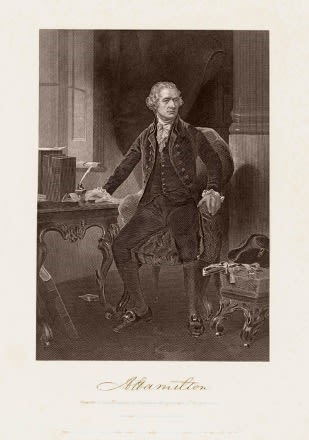

Washington’s trip home had already been scheduled before the rise of the fever. Congress had ended its session and was not expected to reconvene until fall. This allowed for a convenient time for relaxation and rest back at Mount Vernon. The President was also expected to lay the new cornerstone for the Capitol building being constructed in the District of Columbia. By September the fever began to raise its head close to home. Washington’s neighbor, Dr. Wistar, had contracted the disease. On the 6th he learned that his own Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and his wife had contracted the disease.

On the 25th, Washington wrote to his personal secretary, Tobias Lear, who would lose his own wife to the epidemic,

“We remained in Philadelphia until the 10th. instr. It was my wish to have continued there longer; but as Mrs. Washington was unwilling to leave me surrounded by the malignant fever wch. prevailed, I could not think of hazarding her and the Children any longer by my continuance in the City the house in which we lived being, in a manner blocaded, by the disorder and was becoming every day more and more fatal; I therefore came off with them on the above day and arrived at this place the 14th. without encountering the least accident on the Road.”

By November, the epidemic has subsided, probably by the disease having run its course and the cooling weather. The Federal Government began to return, though first to nearby Germantown. The Yellow Fever epidemic would alter Philadelphia forever. Modern estimations put the death toll at 6 to 10 percent of Philadelphia’s population. But the city would survive and take action to reduce the chances of future outbreaks or epidemics. Hospitals were built. Ordinances were passed to clean the city. A modern water system was designed to provide healthy drinking water.

The difficult circumstances of 1793 challenged our new government and the American people, but ultimately both persevered. Philadelphia and our young Federal Government suffered, survived, and was strengthened by its experience, just as we shall our present one.

Ron Carnegie has worked for Colonial Williamsburg for almost 25 years. He has been involved in many different aspects of Colonial Williamsburg’s various activities, most recently portraying George Washington.

Resources

Arnebeck, Bob. “A Short History of Yellow fever in the US.” Benjamin Rush, Yellow fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine. 2008. 20 May 2010 < http://bobarnebeck.com/history.html>

Murphy, Jim. An American Plague: The True and Terrifying Story of the Yellow fever Epidemic of 1793. New York: Clarion Books, 2003.

Powell, J. H. Bring Out Your Dead; the Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793. Special edition, Time Reading program. New York: Time inc., 1965.

Founders Online (Primary Source Letters)

Washington to Hamilton September 6th 1793 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-14-02-0028

Washington to Knox September 9th 1793 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-14-02-0066

Washington to Lear September 25th 1793 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-14-02-0095