The story of Mary Edwards, an 18th-century woman who worked for decades as a human computer

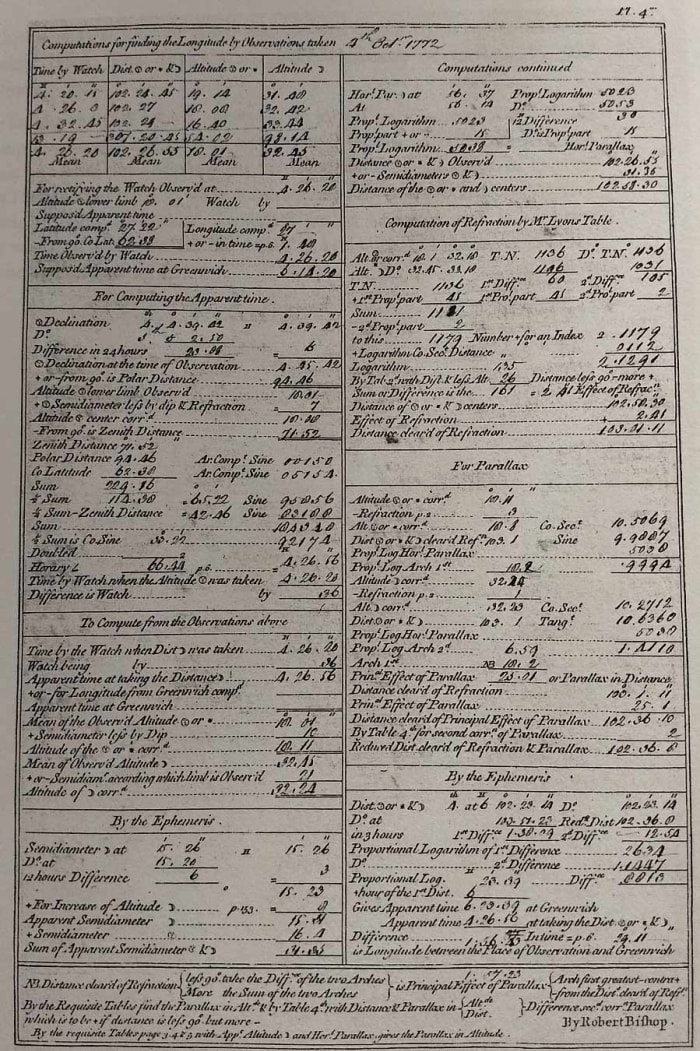

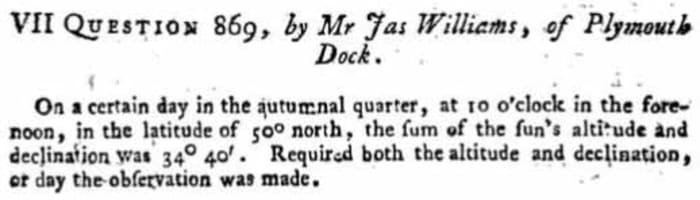

Finding a practical yet reliable method for determining longitude at sea was one of the major scientific quandaries of the 18th century. In 1759, John Harrison debuted his H4 chronometer which ran reliably enough to make the longitude calculation a simple multiplication problem. Unfortunately, devices like Harrison’s “longitude watch” remained prohibitively expensive for decades afterward. Another likely solution was the “lunar-distance method,” where the navigator measured the angular distance between the moon and the sun or the moon and a fixed star, then interpolated the difference between apparent time at Greenwich and their own location to determine longitude.

While this method worked reasonably well, the many complex calculations were time consuming. Using a reference like the British Mariner’s Guide, the calculations required corrections for refraction and parallax, computing the positions of celestial bodies and their distance from one another, their angular distance from Greenwich at a specific time, and more. The operation took upwards of four hours to complete.

Then in the 1760s, Nevil Maskelyne, the British Astronomer Royal (often unfairly vilified in the Harrison story), supervised the compilation and publication of the Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Published annually (and occasionally sold in Williamsburg by the 1770s), the Nautical Almanac contained sets of precomputed tables and corrections that dramatically reduced the time needed to compute longitude from four hours to a much more practical 30 minutes.

Computing tables for the Nautical Almanac was no easy feat. Maskelyne hired two “computers” to prepare the tables for the first six months of a given year, two more for the second six months, and a “comparer” to check the computers’ work and correct mistakes. In 1773, a preacher and amateur astronomer named John Edwards was hired as a computer, earning six pounds and five shillings for each month’s worth of completed tables. He also experimented with various metals to improve the quality of telescope mirrors. One day in 1784 while working on a new mirror, John Edwards died after inhaling arsenic fumes. His widow, Mary, now had to find a way to provide for herself and her two daughters.

Fortunately, Mary Edwards had to look no further than the Nautical Almanac. As it turns out, Mary had been doing nearly all her husband’s computer work since Maskelyne had first hired him. In 1784, she applied to Maskelyne directly and asked to continue computing for the almanac in her own name. Surprisingly, Maskelyne and the Board of Longitude agreed, and began paying Mary for her work with no apparent break in her income. It isn’t known how Mary acquired the mathematical education necessary to work as a computer (she could have learned from John, or perhaps her father or brother), but she was very good at it. Not long after her husband’s death, Mary was regularly trusted with computing a full year’s worth of tables, effectively carrying half of the almanac’s computing load on her own.

The Nautical Almanac had to be published each year because its astronomical data changed steadily over time; the tables for 1773 would not be accurate in 1774, for example. In addition, Maskelyne wanted to have the almanac published several years in advance so sailors on long voyages (such as Captain Cook’s 1768-1771 circumnavigation of the world) could take several editions to sea. Unfortunately, Mary Edwards and her colleagues had grown so efficient at computing their tables that by 1793, the almanac was being printed ten years in advance. As a result, the Board of Longitude suspended computing work for more than four years. Totally dependent on the Nautical Almanac for financial support, Mary joined her fellow computers in appealing to the Board of Longitude for lost wages. Mary was awarded £34 as a “loss of time payment,” and Maskelyne was able to secure her other computing work in the meantime. When work on the Nautical Almanac resumed in 1797, she returned to preparing a full year’s worth of tables.

As time progressed, Mary’s daughters (Eliza Edwards in particular) began to help with the computing work. With the death of comparer Malachy Hitchins in 1809, Mary began comparing six months of tables while still computing six months for each almanac, with a significant pay increase, until a permanent replacement for Hitchins was hired later that year. In response to skyrocketing inflation brought on by the Napoleonic Wars, the Board of Longitude increased a computer’s pay to £225 and a comparer’s to £250 per almanac. (A computer’s pay for the original 1767 Nautical Almanac was a mere £70.) For each full almanac Mary Edwards computed, she was making nearly £24 more than a newly posted captain in the Royal Navy earned in a year.

Nevil Maskelyne’s death in 1811 brought more difficult times for Mary. Her computing assignment was reduced to eight months of tables per almanac, and while petitions to the Board of Longitude and House of Commons netted Mary being paid 12 months’ worth of wages for eight months of tables, she never resumed the more lucrative comparing work. Upon Mary’s death in 1815, Eliza Edwards continued her mother’s tradition of computing for the Nautical Almanac until the work was centralized in London as a branch of civil service and thereby closed to women.

Between 1765 and 1811, some 35 computers were hired to prepare tables for the Nautical Almanac, but Mary Edwards was the only woman. Unlike women working in other cottage industries in England who could come together for mutual support, Mary and her daughters worked in near-isolation. While some women of leisure solved mathematical problems included in the Ladies’ Diary as an intellectual exercise, Mary worked as a computer specifically to support her family. Her contributions to the Nautical Almanac (and those of other women in scientific occupations at the time) went unnoticed by the public for many years, but countless numbers of ocean-going navigators made it safely to their destinations using Mary Edwards’s work as their guide.

Michael Romero is a Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter working in both Orientation and Public Sites. Since 2016, he has been working to bring 18th- century naval history to life. Michael has published work in Naval History magazine and NAI’s Legacy, and recently began work towards a master’s Degree in Military History.

For further Reading

- Croarken, Mary. “Mary Edwards: Computing for a Living in 18th Century England.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 25, no. 4 (Oct.-Dec. 2003): 9-15.

- Great Britain, Privy Council. Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea. London, 1808.

- Howse, Derek. Nevil Maskelyne: The Seaman’s Astronomer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Pain, Stephanie. “Lady of Longitude.” New Scientist no. 2438 (13 March 2004).

Learn More

Related Events

-

Presentation: Finding Jane Vobe

A sneak peek behind the scenes into the research behind Colonial Williamsburg's newest Nation Builder Jane Vobe.

CW Admission

-

Performance: Visit with Ann Wager

Step into the past with Ann Wager, Educator of free and enslaved children. Through stories and questions, explore the hopes, choices, and challenges she faced.

CW Admission

-

Tour: Women in Trades

Join us for a walking tour discussing the often-surprising realities of women’s labor, skills, and rights in 18th-century Williamsburg and the Colonial Atlantic World.

CW Admission