[Note: this page discusses the separation of enslaved families and reproduces eighteenth-century sources that use racially outdated language.]

When Bernard Moore heard about the sudden death of his brother-in-law John Robinson, he must have felt everything come crashing down. He would be ruined. Robinson was one the towering figures of Virginia politics. He was the longtime Speaker of the House of Burgesses. And soon after his death, the entire colony learned that he had been corrupt. As the colony’s treasurer, Robinson had illegally loaned government funds to cash-strapped friends and family, including Moore.

Moore was a wealthy enslaver with a vast plantation in King William County, Virginia. Like many of the colony’s leading landowners, he was also deeply in debt. With the tobacco boom fading, Moore had borrowed money from Robinson to invest in a new iron forge. But Robinson had died before the investment could pay off.

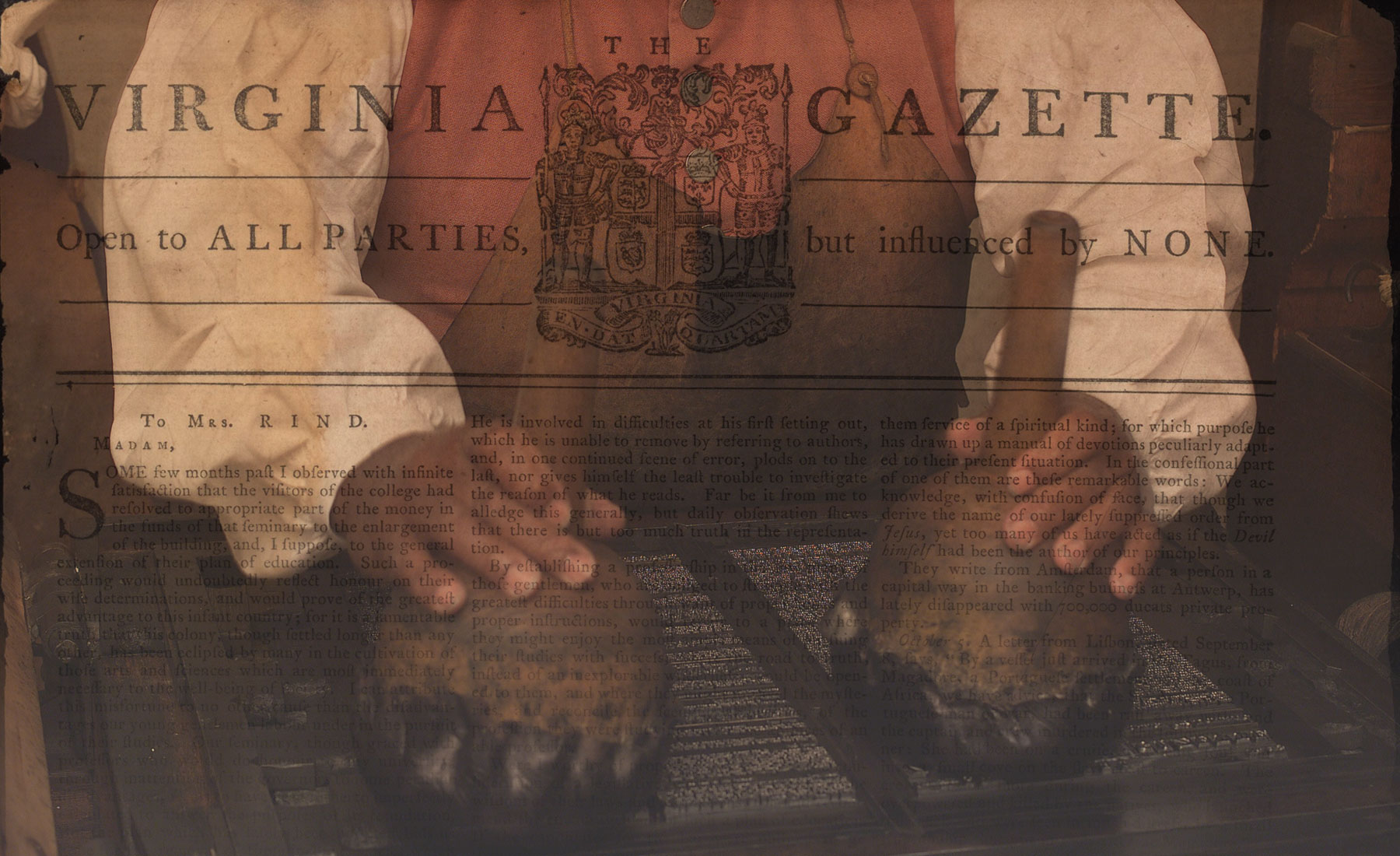

As Robinson’s fraudulent scheme unraveled, his estate demanded that Moore and others repay their loans so that the money could be returned to the colony’s coffers. Knowing that no single individual could purchase his entire estate, Moore divided up most of his property into 124 prizes and created a lottery. In a half-page advertisement in the Virginia Gazette, he announced that he would sell 1,840 lottery tickets at ten pounds apiece. Among the lottery’s possible prizes were some large tracts of land, several herds of cattle, a team of horses, and dozens of enslaved human beings. 1

Family Separation and Slavery

Some enslavers in early America believed that it was cruel to separate enslaved families. George Washington, among others, once wrote that it was “much against my own inclination” to “hurt the feelings of those unhappy people by a separation of man and wife, or of families.”2

But in the face of mounting debts, some set aside these moral objections.3 In response to estate troubles in 1757, for example, Peter Randolph advised William Byrd III to “sell the young Negroes, for it will by no means answer to sell the workers. The only objection to this scheme is, that it will be cruel to part them from their parents, but what can be done.”4 Sales and year-long hires of enslaved people frequently separated enslaved people from their families.5 Moore’s lottery left some enslaved families intact. But it also placed some family members into separate lots.

The advertisement for his lottery identified some of the family relationships between the enslaved people being offered as lottery prizes. Most of the married couples that were identified, such as Billy and Lucy, were placed in the same lot.

But Dorah was included in the lottery, while her husband Jemmy, a carpenter, was not.

Some parents were kept with their children. Enslavers usually kept smaller children with their mother, but were more willing to separate older children.6 While an enslaved woman named Pat would keep four children, her fourteen-year-old son Phill was placed in a separate lot.7

Kate would be separated from her daughter Aggy and her son Nat.

Two young women named Sukey and Betty would be separated from their parents Robin and Bella.

Even if they were owned by the same person, enslaved families did not necessarily live under the same roof. Some of these families may have already been spread across Bernard Moore’s vast land holdings. Despite such challenges, though, family relationships had endured for enslaved people like Sukey, Betty, Aggy, Nat, Phill, and Dorah. The lottery cut these ties.

We have no evidence indicating how these enslaved people reacted to the lottery. But the anguish of enslaved people in these circumstances is well-documented. Several years after Moore’s lottery, an enslaved boy named Charles Ball was sold away from his family in Maryland. He described the scene decades later: “my poor mother, when she saw me leaving her for the last time, ran after me, took me down from the horse, clasped me in her arms, and wept loudly and bitterly over me.” When she asked Charles’s new enslaver to purchase the entire family, she was beaten and he was carried away: “as we advanced, the cries of my poor parent became more and more indistinct—at length they died away in the distance, and I never again heard the voice of my poor mother. Young as I was, the horrors of that day sank deeply into my heart.”8

The Lottery

Lotteries were very popular in colonial America. They were widely used to support community projects, to raise government funds, and to help desperate men pay their debts. Indeed, there might have been no Virginia without a lottery. In its early days, the Virginia Company had partly financed its colonization of the Chesapeake by conducting lotteries in London.9

Moore’s lottery was not the only time that enslaved people were included in a lottery. In 1767, Williamsburg milliner Sarah Pitt proposed a lottery with a top prize of an enslaved sixteen-year-old woman named Doll and her eleven-month-old son Jonathan.10

Moore’s lottery received considerable attention. That was partly because some of Virginia’s most prominent citizens had signed on as managers. George Washington, John Randolph, Archibald Cary, Richard Henry Lee, Edmund Pendleton, and others helped to sell tickets and promote interest in the lottery. Pendleton was the executor of Robinson’s estate. Moore also owed money to Washington’s wife Martha.11 These creditors hoped to ensure that Moore’s lottery succeeded so that they could collect what they were owed.

According to Washington’s diary, he spent the evening of December 8, 1769 “engagd. At Charlton’s abt. Colo. Moore’s Lotty.” As one of the managers, he was probably involved in planning the drawing. It was held over three evenings, at Wetherburn’s Tavern in Williamsburg.12 Someone who purchased a ticket would draw a lottery ball, which contained either a “blank” or a paper listing a prize.13

Despite widespread interest, Moore’s lottery failed to sell enough tickets to discharge his debts. Having apparently purchased some of his own tickets, he tried to sell two enslaved people, named Ralph and Toby, who he had won.14 In late 1770, Moore announced in the newspaper that he had handed over the rest of his property to his creditors.15 A few months later, they were advertising the land that Moore lived on.16 A couple of years before he died, Moore managed to convince Washington to loan him a hundred pounds to purchase more enslaved people to work some of his remaining land. 17

In his advertisement for the lottery, Moore had listed an “outlandish Fellow” named Tom as a prize. The term “outlandish” meant that he was born in Africa and probably did not speak fluent English.18 Perhaps for that reason, the lottery advertisement listed Tom as one of the less valuable enslaved men.

A few months after the lottery concluded, another advertisement in the Virginia Gazette announced that Tom, who “formerly belonged to Col. Bernard Moore,” had been imprisoned as a runaway in Caroline County. Apparently one of the many members of Virginia’s Randolph family had won Tom in the lottery. But while Tom knew he was now enslaved by “one of the Randolphs, on James river,” he “cannot tell which.”19 Disoriented by the sudden changes created by the lottery, Tom was uncertain as to which member of the Virginia gentry now enslaved him.

Moore’s lottery of enslaved people was an unusual event. But across the slave societies of the early modern world, the separation of enslaved families was not. While most enslaved people did not have their fate sealed within a lottery ball, their relationships were just as vulnerable to enslavers’ whims.

Learn More

Sources

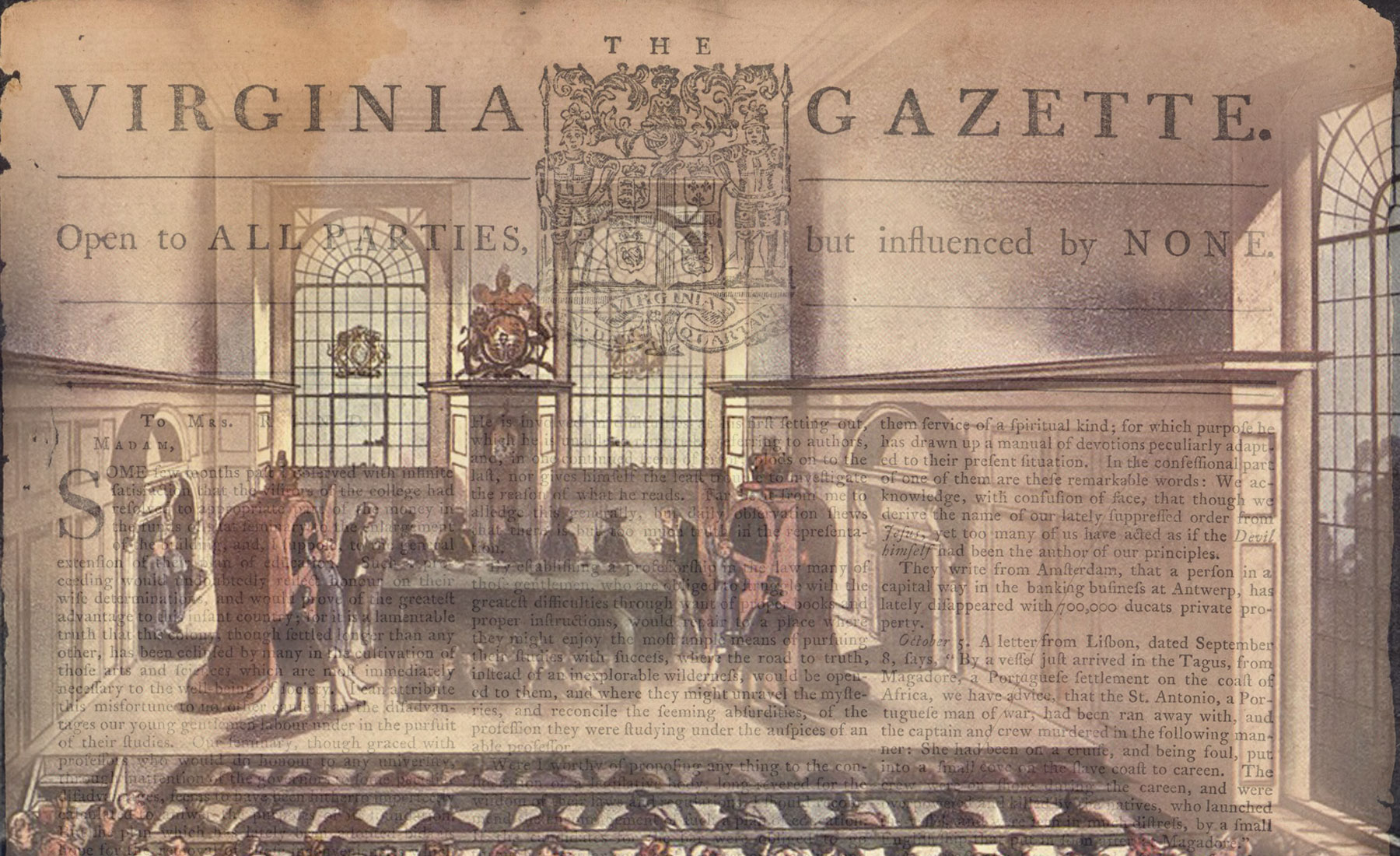

Cover image: An 1809 illustration of a London lottery drawing. Source: W. H. Pyne, et al., Microcosm of London; or, London in miniature, vol. 2 (London: Methuen & Co., 1904).

- Basic biographical information about Moore is available at “The Gorsuch and Lovelace Families (Continued),” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 25, no. 4 (Oct. 1917): 435–36. On the Robinson scandal, see Jack P. Greene, “‘Virtus et Libertas’: Political Culture, Social Change, and the Origins of the American Revolution in Virginia, 1763–1766,” in The Southern Experience in the American Revolution, ed. Jeffrey J. Crow and Larry E. Tise (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 86–100. See also Jon Kukla, Speakers and clerks of the Virginia House of Burgesses, 1643-1776 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1981), 24, 126, 128; Jon Kukla, Mr. Jefferson’s Women (New York: Knopf, 2007), 46–47.

- “From George Washington to John Francis Mercer, 24 November 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0353.

- Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 512–3.

- The Correspondence of the three William Byrds of Westover, Virginia, 1684–1776 (Charlottesville: Virginia Historical Society, 1977), 2:628.

- Brenda Stevenson, Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 161; Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves, 358–64; John J. Zaborney, Slaves for Hire: Renting Enslaved Laborers in Antebellum Virginia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 2012), 11–12.

- Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1986), 359; Morgan, Slave Counterpoint, 514.

- It is not certain that these families were separated. However, given that 1,840 tickets were being sold, the odds of a single person “winning” family members in separate lots were very small.

- Charles Ball, Fifty Years in Chains, or The Life of an American Slave (New York: Indianapolis, 1859), 10–11. See also Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

- Neal E. Millikan, Lotteries in Colonial America (New York: Routledge, 2011), 5–11, 22–25.

- Millikan, Lotteries in Colonial America, 28–29.

- On Moore’s debt to the Custis estate, see “To George Washington from Bernard Moore, 21 October 1766,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-07-02-0318; Douglass Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1951), 3:111; Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 179.

- Washington’s diary notes that the lottery was held at “Southalls.” The editors of the Washington Papers note that James Southall was operating the Wetherburn Tavern between 1767 and 1771. See “[December 1769],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-02-02-0004-0032.

- Millikan, Lotteries in Colonial America, 9.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), April 5, 1770, p. 3. He additionally tried to sell land from his own lottery. See also Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Dec. 21, 1769, p. 1.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Nov. 8, 1770, p. 2.

- Virginia Gazette (Rind), Jan. 10, 1771, p. 3.

- See Ledger B, 1773 – 1793, p. 45, George Washington Financial Papers Project, http://financial.gwpapers.org/?q=content/ledger-b-1772-1793-pg46.

- Gerald W. Mullin, Flight and rebellion: slave resistance in eighteenth-century Virginia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 13.

- Virginia Gazette (Rind), July 26, 1770, page 2.