“In France and England, great care is taken to preserve the teeth of children; and hence it is you rarely see a French or an English person, especially a lady, who has not an excellent set of teeth; and it is generally agreed that no one feature of the face contributes so much to its beauty, as clean sound teeth.”

Whether based in vanity, health considerations, or both, a desire to have beautiful teeth connects contemporary people with eighteenth-century Virginians. In fact, our ancestors used implements to clean their teeth long before Williamsburg became Virginia’s capital. Modern sources attribute the first use of such implements to the Babylonians circa 3500 BC. At Babylonian burial sites archaeologists found so-called “chew sticks,” which were twigs that mechanically cleansed the teeth when chewed. The modern toothbrush form consisting of a handle with bristles oriented at right angles first appeared in China during the Tang Dynasty (619-907 AD). The Chinese typically utilized bone or bamboo for the handle, and boar hair for the bristles.

The earliest reference to a toothbrush I find in an English language publication is the inclusion of a “Turkish tooth-brush” in John Tradescant’s 1656 Collection of Rarities. A 1698 surgical text recommended “after eating always wash the Teeth with fair Water and a Brush, to keep them clean.”

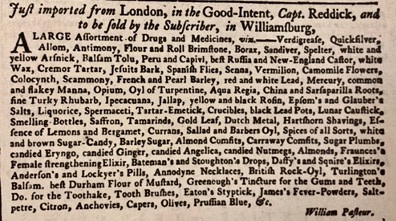

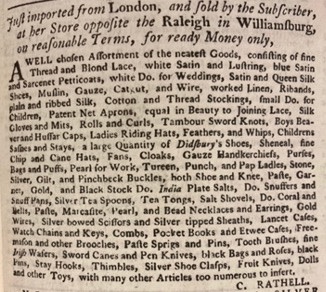

Toothbrushes were widely available to purchase in Virginia’s colonial capital. Apothecary William Pasteur placed the following advertisement in the November 30, 1759, edition of the Virginia Gazette. Note the second-to-last line.

Many other apothecaries placed similar advertisements. However, it was not only medical practitioners selling toothbrushes as one could purchase them from other tradespeople. Catherine Rathell operated a millinery shop in Williamsburg between 1769 and 1775 and placed the following advertisement in the Virginia Gazette on May 5, 1774. “Tooth Brushes” are seen on the fourth line above her name.

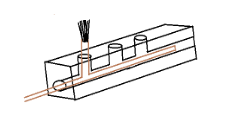

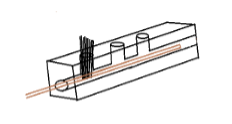

In a privy on the Grissell Hay property (Grissell Hay was the wife of apothecary Peter Hay), Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists discovered the toothbrush seen below. It representative of the brushes commonly available in the 18th and 19th centuries . Carved from bone, the brush has a slight convexity to it. Note that the holes are not precisely standardized to size or location. This is because they were drilled individually freehand. There are five parallel rows of holes. Going from top to bottom, the top row has twenty-four holes, the next also has twenty-four, the middle row has twenty-five, the next twenty-three, and the bottom row consists of twenty-four holes. The brush possesses no extant bristles, but they were likely made of horse or boar hair.

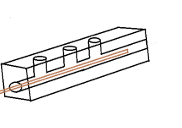

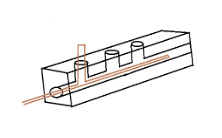

The brush has five holes drilled horizontally into its base, perpendicular to, and connecting with, each of the vertically drilled holes seen above. Copper wire inserted through these holes secured the bristles to the brush. This manner of brush construction is called “trepanning.”

Trepanning a brush consists of the following steps. A loop of copper wire is inserted into one of the horizontal holes.

The wire is pulled up through a vertical hole.

A tuft of bristles is looped under the wire.

The bristles are then secured by pulling the wire taut. Once the bristles are all in place, the horizontal hole is plugged.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has in its collections a toothbrush circa 1793-94. More elegant than a bone toothbrush, this brush’s handle is made of sterling silver. It is notable not only for its refinement, but also for its petiteness, measuring just 4 ¾” long and 1/8” wide at its narrowest point.

Silver was a precious commodity in the eighteenth century. The owner of a silver brush surely expected to use it for a considerable period of time. Although the natural hair bristles of this brush are fixed in its handle, the bristles of some silver-handled toothbrushes may have been contained in a removable insert, permitting their replacement when worn down. Today we can simply replace our electric toothbrush head, while retaining the rechargeable handle.

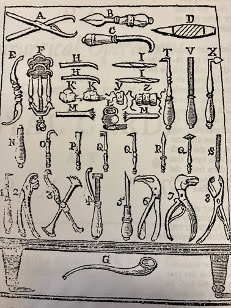

Given that the ancients used twigs as the original toothbrush, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that in the 1700s a similar implement that substituted roots for twigs was used to clean the teeth. The following illustration is from Pierre Dionis’s 1710 A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris. The brushes labeled “M” are marshmallow roots, bristled at one end. Dionis writes that they were used to apply toothpaste to the teeth.

Period texts identify specific roots as proper for making into toothbrushes.

“[T]he roots of some particular plants, especially fibrous and woody ones, are best formed into little brushes for cleaning the teeth, and probably have been substituted in the room of common tooth-brushes, on account of their being softer to the gums, and more conveniently used.”

Lucerne and licorice roots were preferred; marshmallow roots were acceptable. Dentistry and cosmetic books conveyed the recipe for crafting the roots into toothbrushes.

Please be on the lookout for part 2 of this blog, in which I craft a toothbrush from a licorice root.

Mark works at Colonial Williamsburg’s Pasteur and Galt Apothecary Shop, where he is an apprentice. When not working he enjoys spending time with his family.

Resources

Dionis, Pierre. A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris. London: for Jacob Tonson, 1710.

Fauchard, Pierre. The Surgeon Dentist, or Treatise on the Teeth […]. Translated by Lilian Lindsay. London: Butterworth & Co, 1946.

Snow, Michael R. Brushmaking: craft and industry. Headington, Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic Press, 1984.

Zhou, Zhong-Rong, Hai-Yang Yu, Jing Zheng, Lin-Mao Qian, and Yu Yan. Dental Biotribology. New York: Springer Science and Business Media, 2013.

Thank you to Amanda Keller, Tina Gessler, Erin Lopater, and Jason Copes for their assistance with the sterling silver toothbrush, and to Sean Devlin for his help with the bone-handled brush.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.