In Part 1 of this blog, I presented a general discussion of the toothbrushes used in colonial Virginia. One such implement was a brush fabricated from a licorice root. Since dentistry falls within the purview of my apothecary trade, I felt compelled to make a licorice root toothbrush according to eighteenth-century instructions. Live the experience with me as I turn a root into a beautiful work of dental art!

The first step is to procure a root of proper proportions. The desired size is a root the thickness of one’s little finger and about six inches in length. Here are the roots I selected.

The roots are boiled in water several times and drained. Using a penknife, each end of the root is slit into the form of a brush and allowed to dry

thoroughly.

Next, a dye is made using the following recipe.

Brazil wood 4 ounces

Cochineal, bruised 3 drams

Rock alum ½ ounce

Water 4 pints

Boil until the liquid is reduced by half, then strain through a linen cloth.

The roots are soaked in the dye for 24 hours.

They are then removed and allowed to dry slowly.

Two to three coats of gum tragacanth are applied, allowing the gum to dry between coats. Finally, the root is repeatedly coated with Turlington’s Balsam.

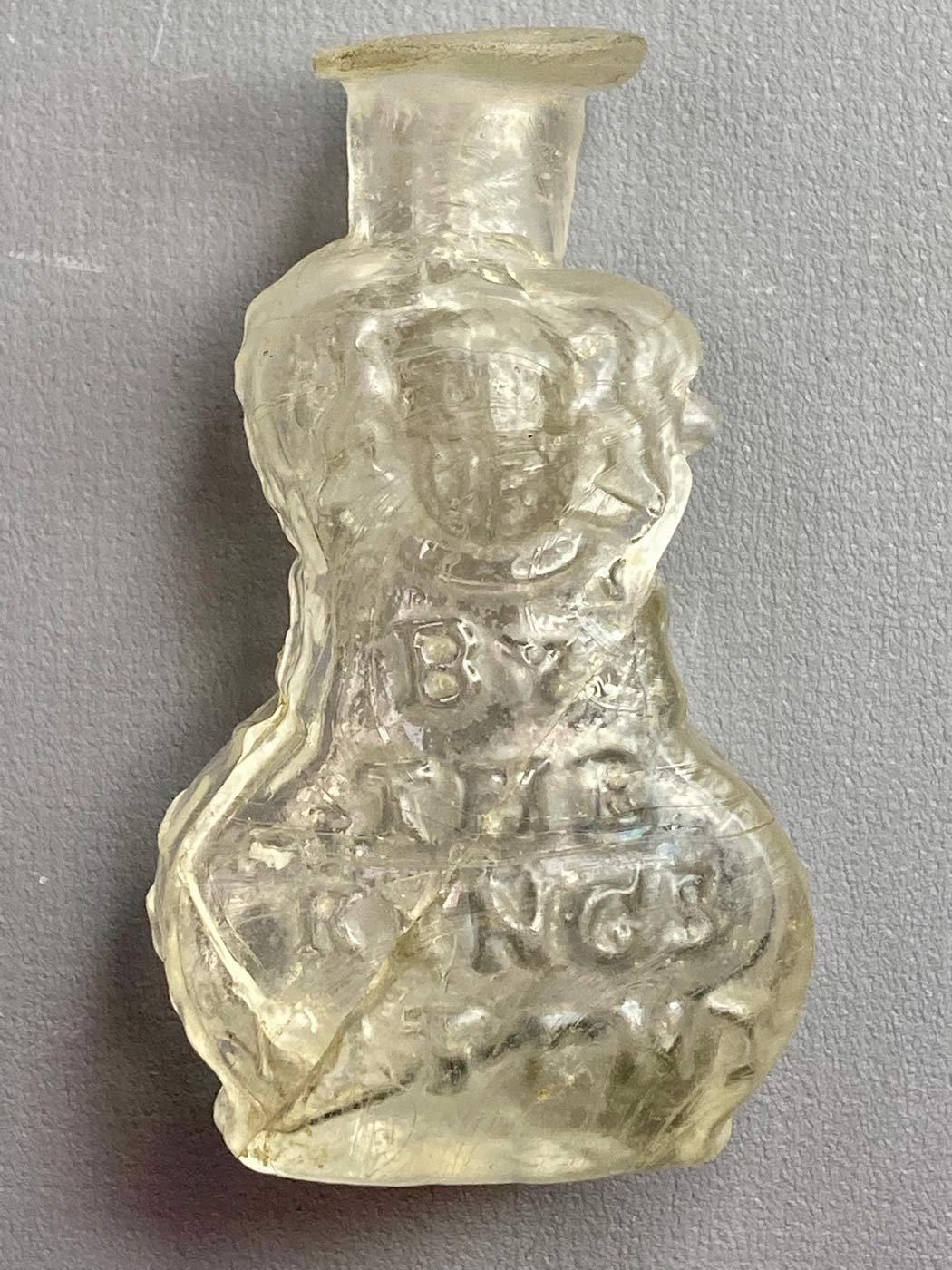

Turlington’s Balsam of Life was a medicine patented by Robert Turlington in 1744 and marketed as a cure for urinary tract stones, colic, and “inward weakness.” It contained upwards of 28 ingredients, including spirits, gums, and aloe. Sold in distinctive glass bottles, it was available in colonial Williamsburg as evidenced by Virginia Gazette merchant advertisements. Appearing January 24, 1771, the following ad listing items available at the Williamsburg Post Office included Turlington’s Original Balsam of Life.

Additional proof of the availability of Turlington’s Balsam in Williamsburg is the Turlington’s Balsam of Life bottle Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists excavated on the grounds of Wetherburn’s Tavern.

Recall from Part 1 of this blog that a root toothbrush was said to be softer to the gums than a bristle toothbrush. When I began this project, I had my doubts as to the veracity of this assertion. To my surprise, after the root is varnished with Turlington’s Balsam its tips are quite smooth. I now believe that it would be softer to the gums than bristles.

Convenience of use was the other reason a root toothbrush was recommended in the eighteenth century. Brush crafting instructions directed the use of a root the size of one’s little finger. The brush’s breadth makes it difficult, if not impossible, to physically apply it to any of the lingual (inner) or the rear buccal (outer) surfaces of the teeth. A modern-style toothbrush consisting of a handle with bristles is easier, and therefore more convenient, to use.

Convenience could also refer to accessibility. For someone living any great distance from a shop selling a modern-style toothbrush, a brush made from a root perhaps could be more conveniently obtained.

However, if convenience meant effortless, I must disagree. Making this brush required boiling the root many times to remove all its juice. Drying was necessary after boiling, after dyeing, and after each coat of gum tragacanth and Turlington’s Balsam was applied. What I am getting at is that crafting a licorice root toothbrush requires a significant investment of time. For me, it took about two weeks to complete.

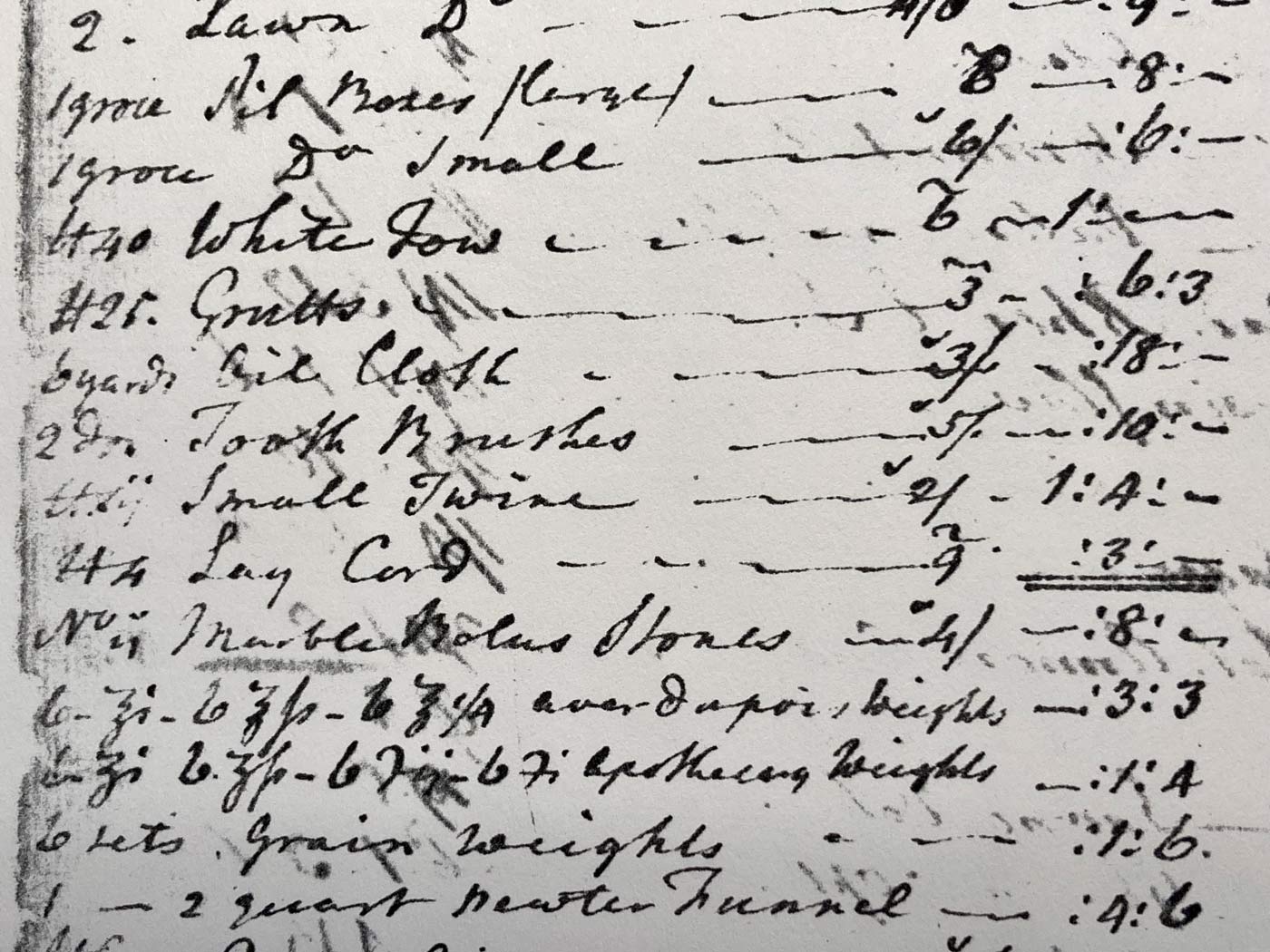

Additionally, making this brush would incur significant costs. One needed to possess a book which contained the recipe. Being imported to Virginia, dye ingredients and gum tragacanth were likely expensive. Conversely, a modern-style toothbrush was relatively inexpensive. We see from apothecary James Carter’s invoice book that in 1767 he purchased toothbrushes for 5 pence apiece, whereas one year later he paid 1 shilling 6 pence (18 pence) for a small bottle of Turlington’s Balsam.

Crafting this licorice root toothbrush was an experience I enjoyed immensely. The brush is not only a beautiful object, but functional as well. Come by the Pasteur & Galt Apothecary Shop to see the brush and to talk more about eighteenth-century dentistry. I’ll leave you with my favorite 1700s quote pertaining to dentistry. Referring to dentists, "‘Tis customary for these Gentlemen to make a present of a Root, and a small Pot of the Opiate, to those who are so Civil as to pay them well."

Mark works at Colonial Williamsburg’s Pasteur and Galt Apothecary Shop, where he is an apprentice. When not working he enjoys spending time with his family.

RESOURCES

Dionis, Pierre. A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Demonstrated in the Royal Garden at Paris. London: for Jacob Tonson, 1710.

Fauchard, Pierre. The Surgeon Dentist, or Treatise on the Teeth […]. Translated by Lilian Lindsay. London: Butterworth & Co, 1946.

Snow, Michael R. Brushmaking: craft and industry. Headington, Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic Press, 1984.

Zhou, Zhong-Rong, Hai-Yang Yu, Jing Zheng, Lin-Mao Qian, and Yu Yan. Dental Biotribology. New York: Springer Science and Business Media, 2013.

Thank you to Sean Devlin, Colonial Williamsburg Archaeology, for his assistance with the Turlington’s Balsam of Life bottle.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.