Teaching birds to sing was part of a much larger culture that was born out of travel to the New World. The 18th century saw a great increase in international travel and commerce. New World explorers discovered wondrous new species of plants and animals, and this sparked many natural history interests and commercial industries that continue today. New species of birds were discovered, and new vocations and artwork sprang up relating to birds and bird catching. Pet birds were taught to sing.

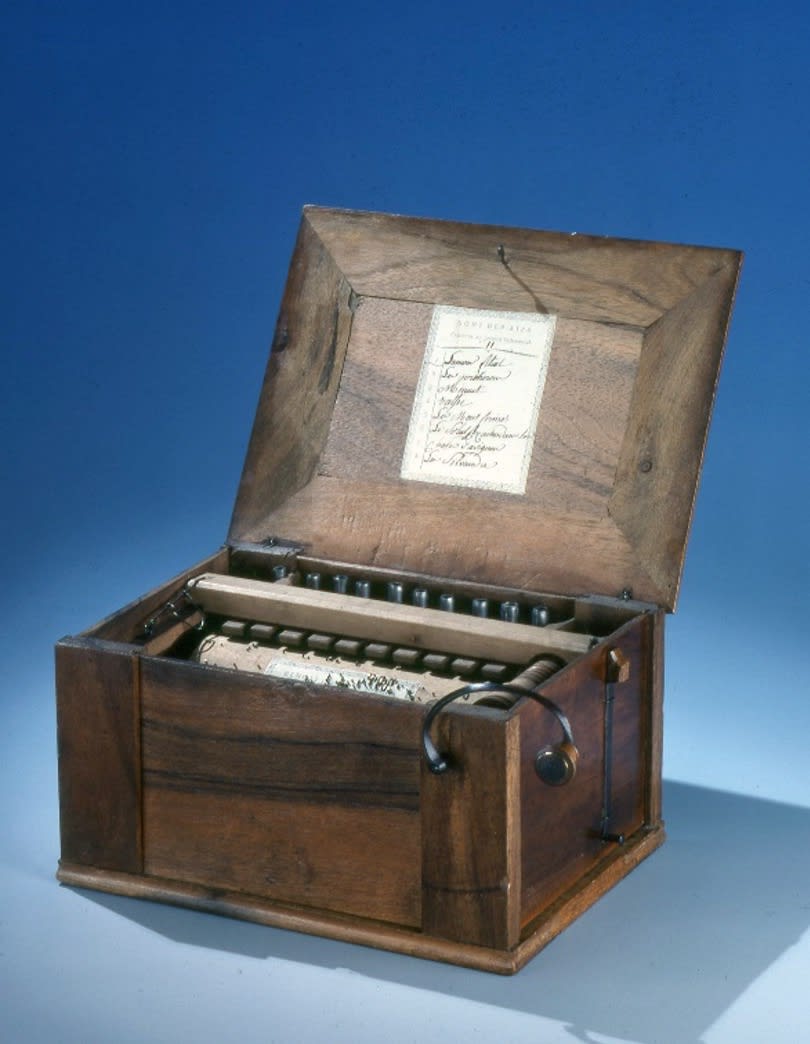

This could be done using a bird organ, or serinette.

Royal governors even joined this trend of owning birds and serinettes. We know that Lord Botetourt owned up bird cages and a serinette was listed in Lord Dunmore’s reparations inventory.

The popularity of using a serinette is evidenced by artwork of the time. Hogarth’s painting, The Graham Children (1742), depicted a gentry family, including a young boy using a serinette to train his pet bird.

The more musically inclined could play a Flageolet or Recorder, using tunes from “The Bird Fanciers Delight.” In 1717, John Meare and John Walsh published separate books by this title. Tunes from the “Beggar’s Opera” and Playford’s “Dancing Master” appeared in both publications. Some tunes were composed to imitate the song patterns of certain species, including bullfinches, canaries, linnets, woodlarks, skylarks, starlings, parrots, nightingales, sparrows, the East India Nightingale, and throstles.

The player placed the bird in a darkened room to play pieces repeatedly, always using the same pipe. The higher the pitch of the instrument, the better, so the bird could hear the tune in its own range. For this purpose, the bird flute, or sopranino recorder, was the favored instrument.

Birds were also available pre-taught to sing their songs. Germans taught bullfinches in small classes. There were several stages of development for their avian students. The first stage was called “chirping,” when the bird began to repeat just small snippets of the tune. The second stage was “calling,” and this meant that the bird could sing back sections of the tune. The third stage was called “recording.” (Perhaps these birds were our first “recording artists!) It could take birds 10 or 11 months to get through this stage where they began to sing most of the tune back. The birds graduated when they could sing the entire song through without any mistakes. At this point, the birds were said to be “singing their Song Round.”

Don’t believe this was possible? Haydn had a parrot who could sing a one-octave scale and the beginning to “Austrian Hymn.” Still don’t believe me? Go to YouTube and search “birds imitating sounds” and hear a lyrebird perfectly imitating the sounds of cameras, car alarms, and chainsaws. If these birds can recreate these sounds today, it is not so hard to imagine that bullfinches could sing the march from Handel’s “Rinaldo” in the 18th century.

Many composers imitated bird song in their sonatas and other instrumental works. Here’s Jenny Edenborn to give you an example:

Telemann is another composer who was inspired by birds, as evidenced by this “Soave” movement from “Six Canonic Sonatas.”

Rameau wrote several selections in his Pièces de Clavecin, 1724 that evoked images of birds in the listener’s mind. Danny Corneliussen highlights two of them in these next two videos. The first is called Le Rappel des Oiseaux, describing a flock of birds flying around.

The second piece is called Le Lardon, describing the sounds made by hot grease popping out of a frying pan while frying chicken.

This madrigal, by Thomas Morley (English Renaissance composer who died in 1602) entitled, “When Lo by Break of Morning,” talks about the birds enamored.

From the madrigal grew a somewhat simpler form of part song called “glees” and this is where we got the term “glee club.” Catches or rounds were also very popular. You have probably sung a catch before, such as Frère Jacques or Row Row Row Your Boat.) This one is entitled “As I Me Walked” from Thomas Ravenscroft’s “Pamelia Musicks Miscellanie” of 1609.

Putting this blog together allowed me to combine my love of birdsong with my love of music and learn more about instruments in the flute family, 18th-century commerce, and the rise of interest in the natural sciences. The next time you come to visit us, please take time while walking through the Historic Area to listen to the birds around you and think about the how birds and composers actually influenced each other in colonial times and how that is still happening today.

Plus, join us for a limited run of the Bird Fancyer’s Delight in the Hennage Auditorium this season.

Dr. Amy Miller began her career at Colonial Williamsburg in 1996, performing for Palace Concerts, Palace Green Echos of Music walking tours, and Dance Our Dearest Diversion programs. In 1998, she became the first female member of the Fifes and Drums of Colonial Williamsburg. In August of 2015, she moved to the Performing Arts department as Site Supervisor of Music in charge of the Governor’s Musick ensemble. Amy performs the role of Mrs. Barnes in Cry Witch and tells ghost stories for Shadows of the Past. She and her husband, Sam, like to spend time with their pets, travel, and watch movies. Amy paints ceramics, sews, knits, and weaves baskets.