The Talented Chef Who Put Travis House on the Map

Today the Travis House contains offices and sits in its original location at the corner of Francis and Henry. But once upon a time, it was a Colonial Williamsburg restaurant at the foot of Palace Green, and it was where a talented chef with an entrepreneurial knack built a national reputation for her take on Southern cuisine.

Travis House first opened its doors on July 3, 1930, serving tasty meals of Brunswick stew, Old Virginia ham, crab meat canapes, spoon bread, candied sweet potatoes, and duck hash on waffles.

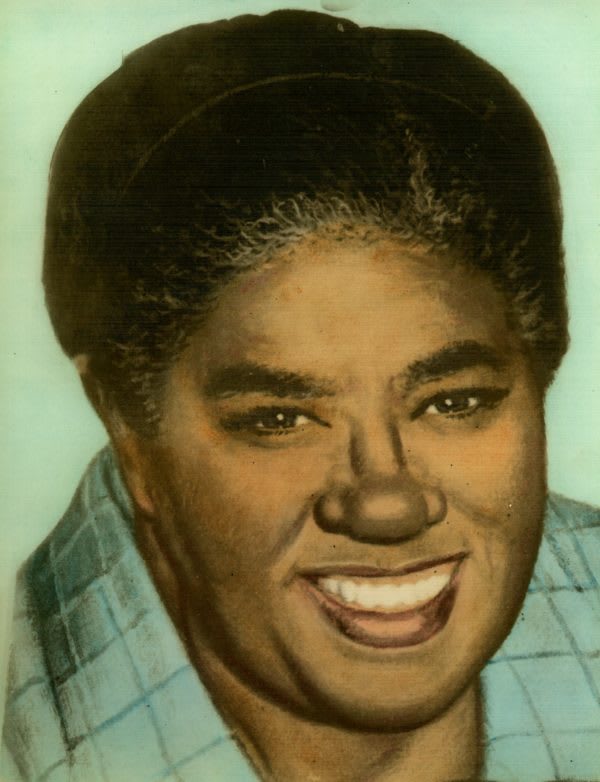

Wartime gasoline rationing and employee shortages forced Travis House to close in June 1942, but management regrouped and was able to reopen January 19, 1943 with a new chef at the helm who was most unusual for her time: Lena Richard.

Born in 1892 in New Roads, Louisiana, Lena Paul Richard got her professional start assisting family members who worked as domestics for socialite Alice Vairin. Vairin saw potential in Richard and sent her to cooking school, first locally in New Orleans and later to Fannie Farmer’s celebrated cooking school in Boston.

“When I got way up there,” she recalled later in a newspaper interview, “I found out in a hurry they can’t teach me much more than I know. I learned things about new desserts and salads. But when it comes to cooking meats, stews, soups, sauces and such dishes we Southern cooks have Northern cooks beat by a mile. That’s not big talk; that’s honest truth.”

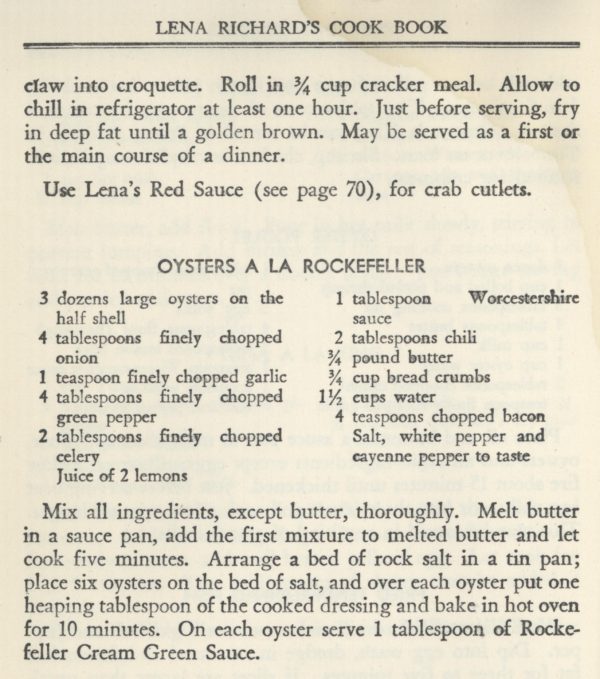

The positive reaction Richard received from her Fannie Farmer colleagues inspired her to write a cookbook, which she published privately in 1939. Boosted by famous food writers Clementine Paddleford and James Beard, Richard earned a contract from Houghton Mifflin to publish her New Orleans Cook Book in 1940. In her preface, Richard called the art of food preparation her “life’s work.”

Richard also suggested a more democratic purpose in making her recipes available. She wrote that she had opened her cooking school so that her students “would become capable of preparing and serving food for any occasion and also that they might be in a position to demand higher wages.” Now, she was promising to reveal the “secrets of Creole cooking” to “ordinary homemakers.” The mysteries of dishes like Court Bouillon and Gillade a la Creole “are no longer dishes prepared in secrecy by French chefs, to be eaten by the rich.”

Made up of both traditional and Richard’s own recipes, it was hailed as the best Creole cook book of its time and soon became a bestseller. Modern food writers point out that Richard’s cookbook was unique in that it openly credited the African American cooks who had influenced both her and New Orleans cuisine in general.

Richard cooked in various places when she returned to New Orleans: Mrs. Vairin’s home, a catering business, a lunch room, and a white women’s club. She and her daughter Marie Richard Rhodes began to give private cooking lessons.

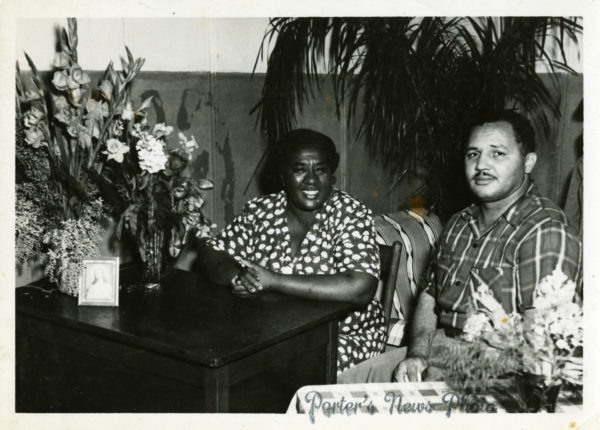

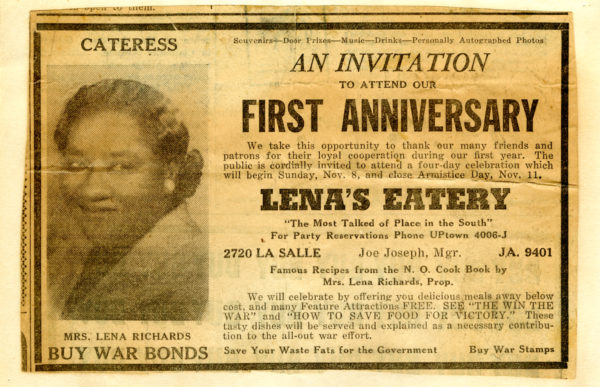

She was briefly lured to New York to be head chef for the Bird and Bottle Inn, then returned to New Orleans and opened Lena’s Eatery in 1941 before coming to Travis House in 1943.

Elizabeth Reynolds, hired to manage the reopened Travis House in 1943, had previously managed a restaurant in New York, where she may have met or become familiar with Richard and her cooking. The New Orleans Cook Book was a popular cookbook, so Reynolds may also have made the connection that way. However it happened, Reynolds hired Richard as head chef for the Travis House, where she remained for about two years.

Richard cooked at the Travis House during wartime when Williamsburg was filled with military personnel from nearby Camp Peary and Fort Eustis. Colonial Williamsburg’s hotels and restaurants were bustling with soldiers and their families looking for respite from war. Richard also cooked for many special guests, including the Foundation’s president, Kenneth Chorley, the British High Command, and Winston Churchill’s wife and daughter.

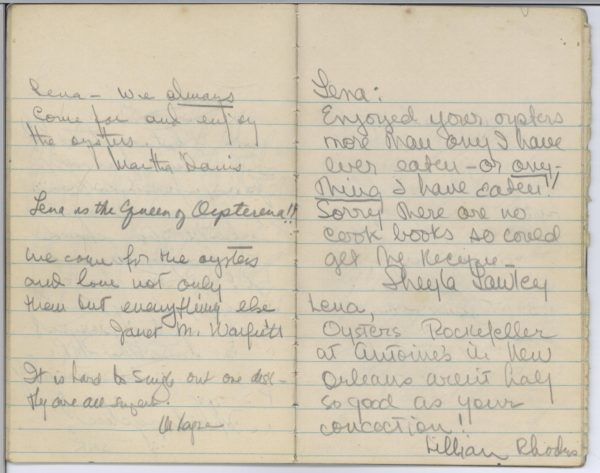

Colonial Williamsburg’s Corporate Archives collection holds two small notebooks of diners’ reviews of Travis House and Richard’s cooking, in particular her Scalloped Oysters, a variation on Oysters Rockefeller. Quotes from the reviews run the rapturous gamut from “Your oysters have character” and “To be scalloped by Lena—the oyster’s prayer” to “Lena is the Queen of Oysterena” and “Your gifted fingers have given the oyster a soul.”

Many declared her oysters the best they’d ever eaten, better even than restaurants in Paris or the famous Oysters Rockefeller at Antoine’s in New Orleans.

John Green, then head of the Williamsburg Inn and Lodge, recalled her other signature dish. “Our specialty, if we could be said to have had one, was Chicken Lena. That was delicious. Many of the Seabees who went out to the Pacific remembered Williamsburg for its Chicken Lena.”

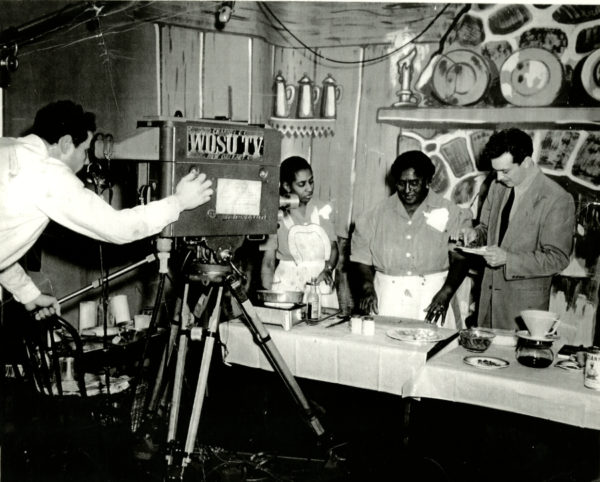

After leaving Williamsburg, Richard returned to New Orleans and restarted her catering business with her daughter. In the late 1940s, she made history as the first African American woman to host a televised cooking show, appearing on the New Orleans station WDSU. She opened another restaurant called Gumbo House and started a frozen foods business that sold her cuisine nationally. She was known around town as “Mama Lena” and people from all walks of life came to eat her delicious food

Richard died unexpectedly of a heart attack in New Orleans in 1950. Her family carried on with Gumbo House until 1958 when it was closed.

Lena Richard was a woman who began as a domestic cook and ended up a nationally known chef with a frozen foods line, a cookbook, a television show, and diners willing to cross the segregation line to eat at her establishments. She was a pioneer who achieved an astonishing amount and though she brought her culinary magic to Colonial Williamsburg for but a brief time, all Travis House diners departed dreaming of her Creole cooking.

Sarah Nerney is an associate archivist in the Corporate Archives and Records department of the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. Her favorite things about the Foundation – which she joined in 2015 – are the oxen, the landscape crew (who can always answer a plant question), stalking the lambs in the spring, and the American Indian interpreters. In her spare time, Sarah likes to lovingly kill houseplants, read mysteries, hang out with her cats, and watch movies in which people with accents wear a selection of amazing hats.