[Note: this page reproduces eighteenth-century sources describing violence against enslaved people and containing racist language.]

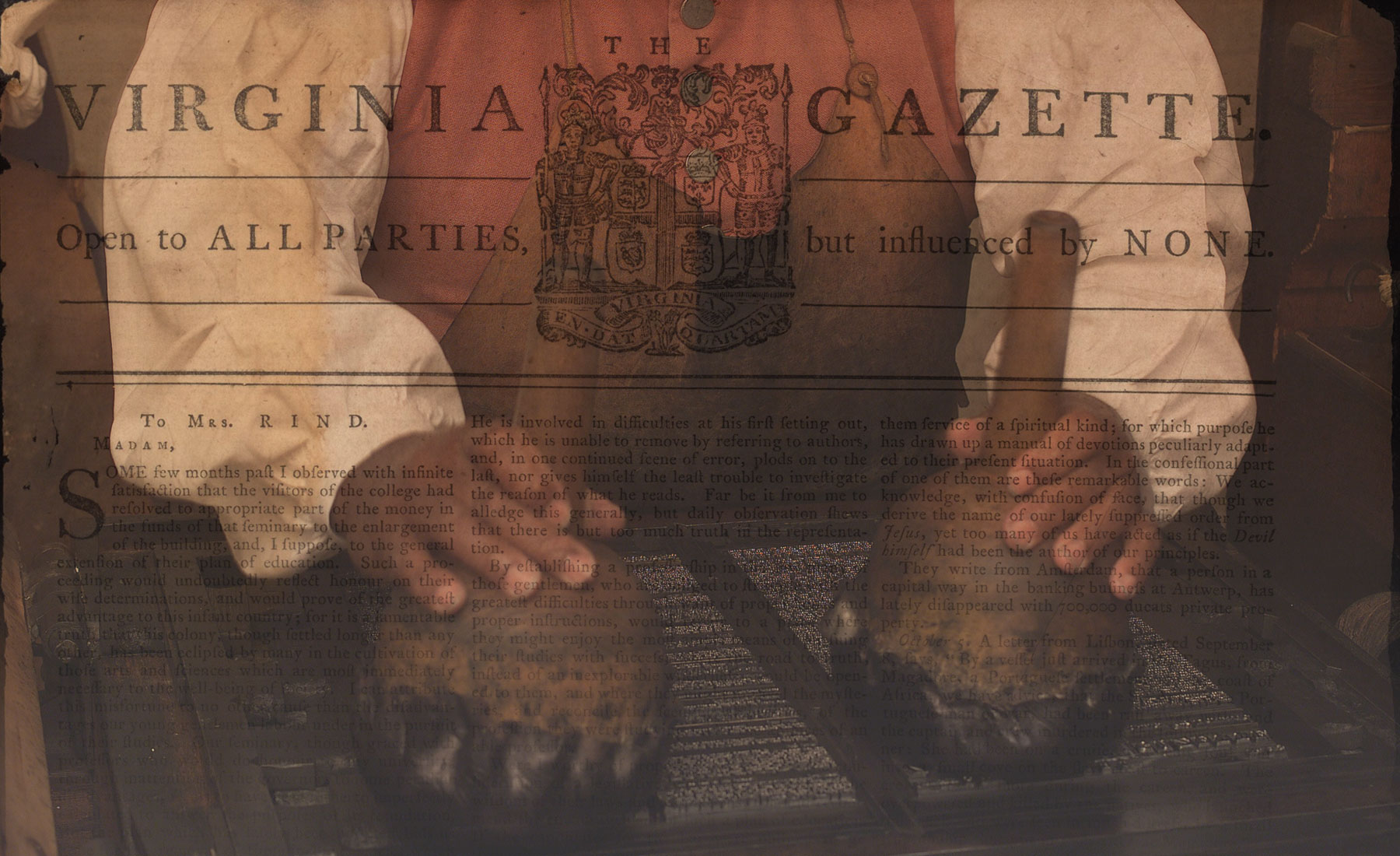

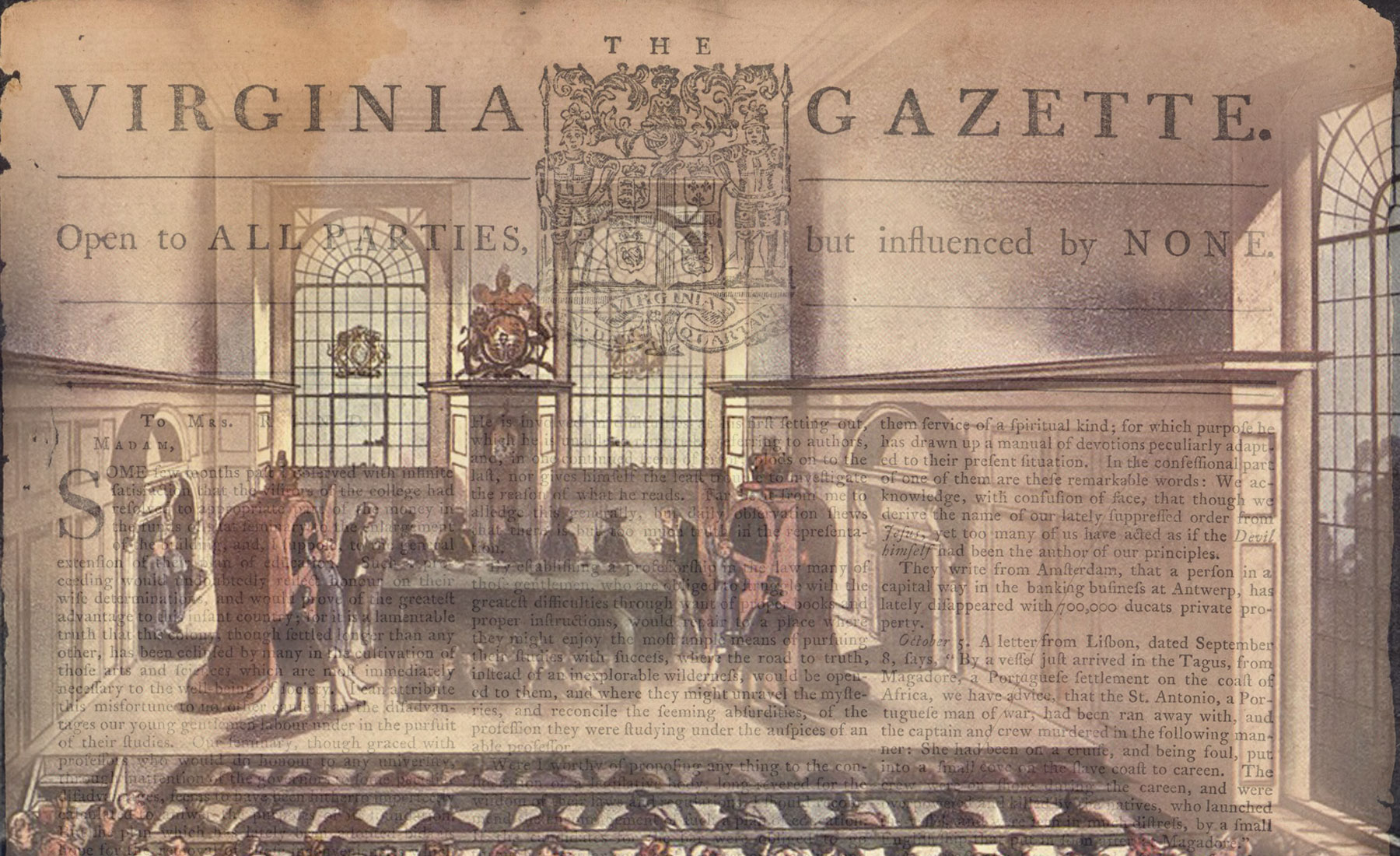

The Virginia Gazettes are one of our best windows onto slavery in early Virginia. Their “runaway” notices document the resistance of enslaved people fleeing bondage. Their pages also brim with advertisements seeking to buy, sell, or hire enslaved people. Read carefully, the Gazettes offer some important clues for understanding eighteenth-century Virginia slavery.

Though we sometimes refer to the Virginia Gazette as if it were a single entity, there were several separate newspapers published in Williamsburg as the Virginia Gazette between 1736 and 1780. Another, unrelated, Virginia Gazette is published in Williamsburg today.

Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library provides free access to its collection of eighteenth-century Virginia Gazette issues. Learn more below about how we can use the pages of the Gazette to better understand the history of slavery in Virginia, and then explore the library’s digitized copies.

Publishing the Virginia Gazette

Enslaved labor helped to produce the Virginia Gazette. Thanks to probate inventories, which record the property of a deceased person, we know that many of the Gazette’s publishers were enslavers. The inventory for William Parks, who published the Gazette from 1736 until 1750, lists enslaved people named Stanton, George, Nan, John, Phillis, Worcester, Ned, Peter, “Lucy and her child,” “Sarah & her Child,” and Ludlow.2 After Parks’s death, his successor William Hunter hired an enslaved man from Parks’s estate.3

After Hunter, the printer Joseph Royle published the Gazette until he died in 1765. An inventory of Royle’s property includes one unnamed enslaved woman, two unnamed enslaved girls, and “two Negro Men named Matt, and Aberdeen.”4 Royle was succeeded by Alexander Purdie, who printed the Gazette from 1765 until his death in 1779. A probate record listed thirteen individuals belonging to Purdie: Jordan, John, Sally, Harry, Jenny, Sukey, Arthur, Esther, Judy, Jack Booker, Alice, Billy, and Betty. According to this assessment, these enslaved people made up the bulk of Purdie’s fortune.5 The probate record for William Rind, whose Virginia Gazette began in 1766, also includes an enslaved man named Dick.6

Some of the enslaved people listed in these probate records may not have worked in the print shop. But most of them probably did. It was not unusual for enslaved people to work on the production and distribution of newspapers in eighteenth-century North America.7 At least some of the people enslaved by the Virginia Gazette’s publishers likely worked in its production and distribution. For example, one expense report that Purdie created listed the labor of “Two Negroes, at £50 each, for Pressmen.”8

Self-emancipation in the Virginia Gazette

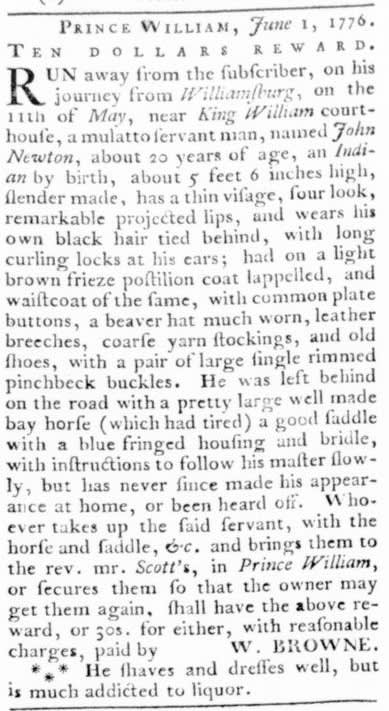

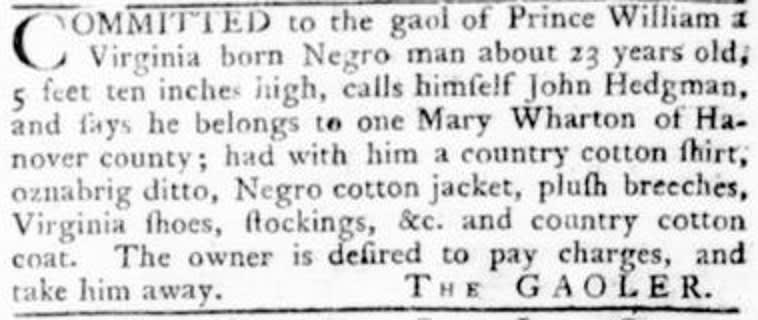

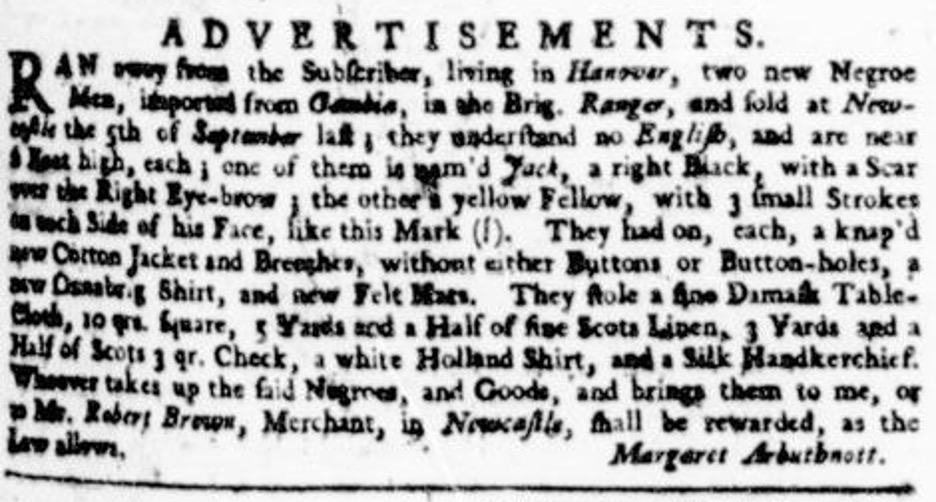

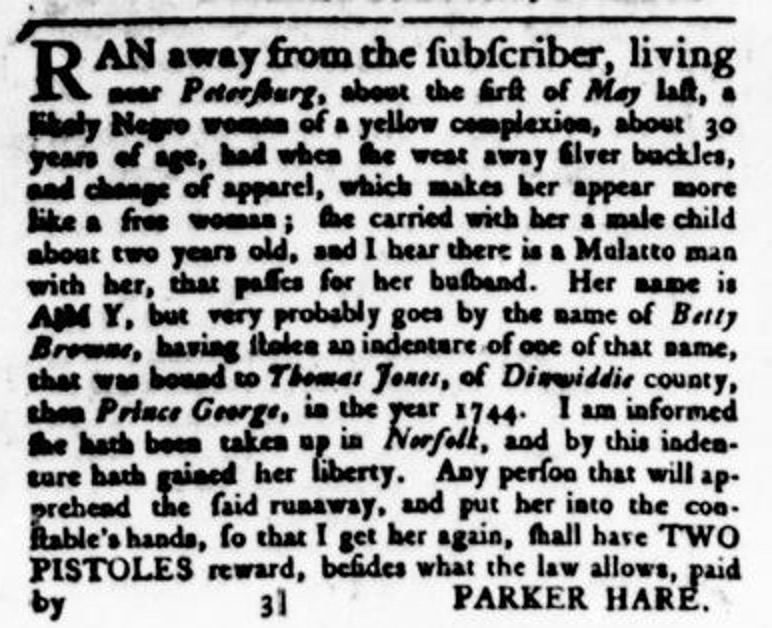

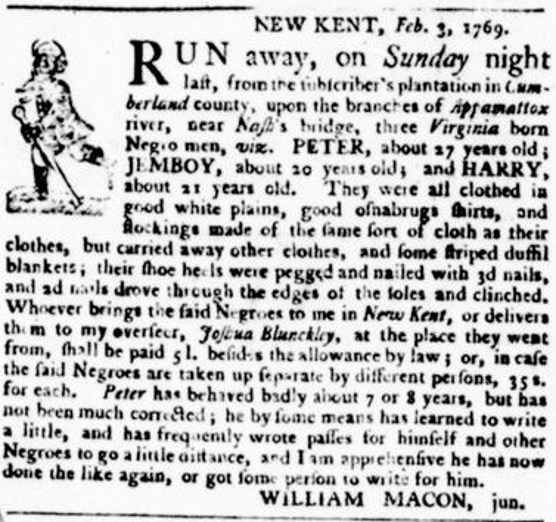

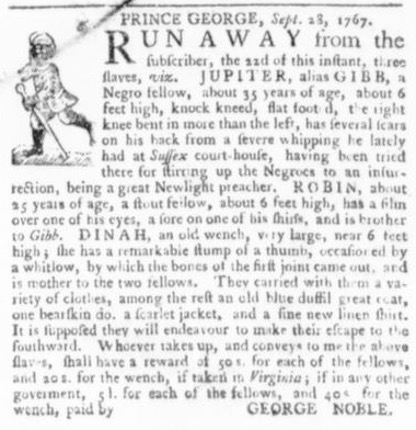

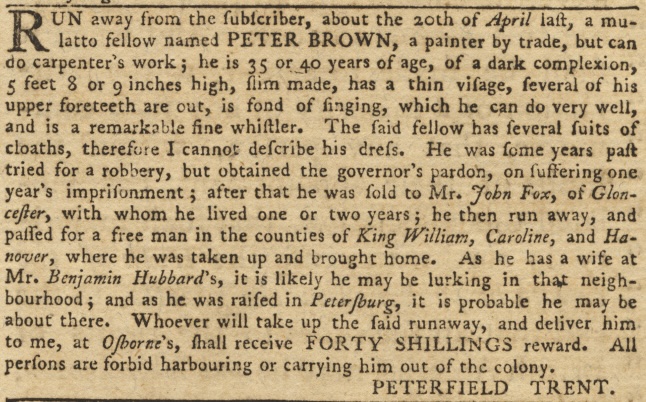

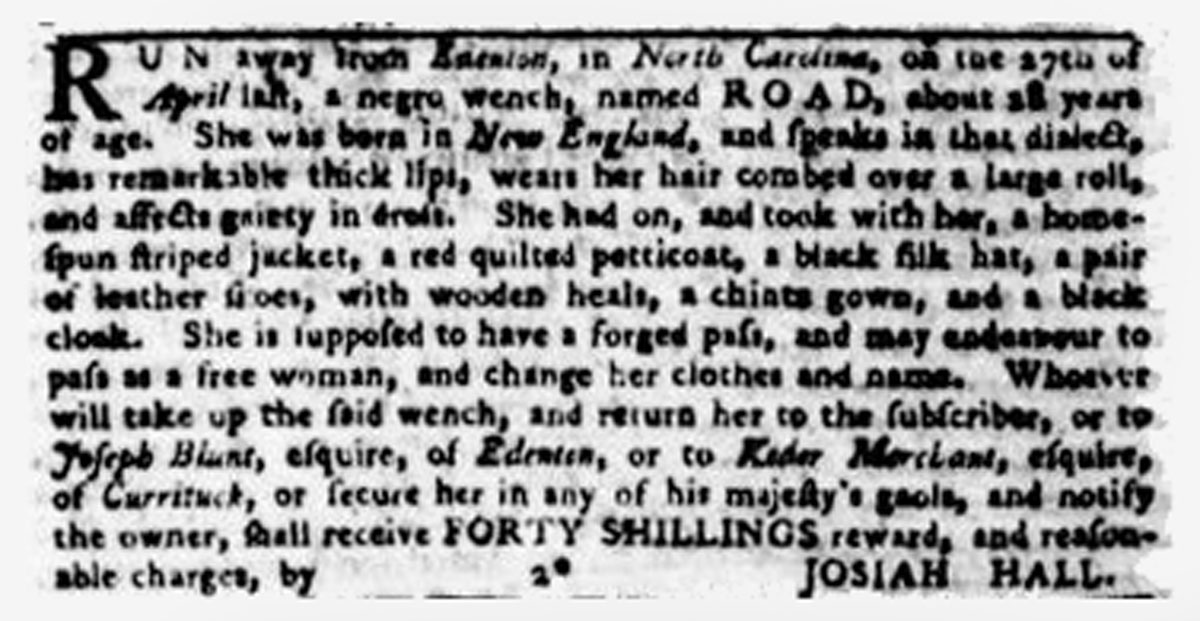

Enslaved people often emancipated themselves by running away from their enslavers. When this happened, many enslavers placed “runaway” advertisements in nearby newspapers to alert others. Aiming to recover the escaped enslaved person, they made every effort to accurately describe their physical appearance. Advertisements for self-emancipated people often noted the escaped person’s complexion, their clothes, and their apparent heritage.

Go deeper : Five advertisements for an enslaved man named Aaron Griffin published in the Virginia Gazette document his prolonged struggle for freedom from Henry Randolph.

Enslaved people used all their skills and knowledge when they escaped. Because certain skills were distinctive, enslavers often described the escaped person’s abilities in print.

Among the most important of these skills was literacy. In the eighteenth century, a small but significant number of enslaved people in Virginia could read and write. The Williamsburg Bray School, for example, taught hundreds of free and enslaved Black students from 1760 to 1774. Its white supporters hoped that schooling would teach enslaved people to be “faithful & honest in their Masters Service.”10 But some white Virginians viewed the literacy of enslaved people as dangerous. In the early nineteenth century, the Virginia government outlawed the education of enslaved people. 11

Go deeper: What did enslaved women look like? What did they wear? What did their hair look like? What complexion were they? Advertisements for self-emancipated people in the Virginia Gazette can help us to answer those questions.

Enslavers often revealed the personal histories of formerly enslaved people in the advertisements seeking them. Some enslavers provided enough biographical detail that it’s possible to imagine what freedom might have looked like to the self-emancipated person. What were their tactics? What were their intentions? What were their hopes?

Go deeper. Explore and search Virginia and Maryland runaway advertisements at The Geography of Slavery website.

The Virginia Gazette and the Slave Trade

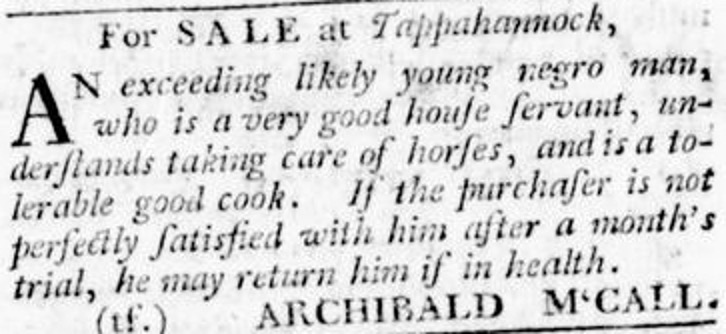

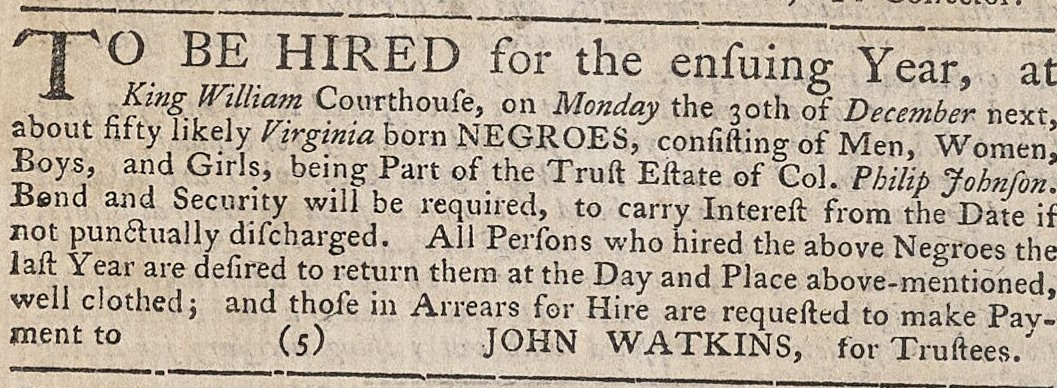

The Virginia Gazette was an important tool for promoting the internal slave trade of eighteenth-century Virginia. The newspaper connected buyers with sellers, and owners with those looking to hire enslaved people. Compared to advertisements for self-emancipated people, notices about buying or selling enslaved people usually contained less detail about the enslaved people in question. They rarely mention their names. Yet these advertisements can help us to better understand how the internal slave trade operated in the eighteenth century.

Learn more: In 1768, a Virginia planter named Bernard Moore organized a lottery to settle his debts. More than fifty enslaved people were included as prizes. Go deeper.

Conclusion

Human bondage touched every aspect of life in eighteenth-century Virginia. The Virginia Gazettes were a product of this slave society. Many of their pages were produced by the labor of enslaved people. They were partly funded by advertisements seeking to recover and re-enslave self-emancipated people as well as those seeking to trade enslaved people. By aiding the recovery and sale of enslaved people, the Gazettes actively supported slavery. Despite this, the Virginia Gazettes remain some of our most important sources for understanding eighteenth-century Virginia, including its enslaved inhabitants.

Learn More

Listen to Ben Franklin's World Podcast

Episode 322: Karen Cook-Bell, Running From Bondage in Revolutionary America

Karen Cook-Bell, an Associate Professor of History at Bowie State University, joins us to investigate the experiences of enslaved women who fled their bondage for the British Army’s promise of freedom.

Episode 137: Erica Dunbar, The Washingtons’ Runaway Slave, Ona Judge

Erica Dunbar, a Professor of Black American Studies and History at the University of Delaware and author of Never Caught: The Washington’s Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave Ona Judge, leads us through the early American life of Ona Judge.

Further Reading

Sources

- David Waldstreicher, “Reading the Runaways: Self-Fashioning, Print Culture, and Confidence in Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic,” William and Mary Quarterly 56, no. 2 (April 1999): 249–51.

- “Appraisement of William Parks’ Personal Estate in Hanover County,” in Mary Goodwin, “Printing Office and Post Office Historical (LL) Report, Block 18 Building 12B Lot 48,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series – 1420, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, xi.

- Goodwin, “Printing Office and Post Office Historical (LL) Report,” 12.

- Goodwin, “Printing Office and Post Office Historical (LL) Report,” xl.

- “Appraisement of the Estate of Alexander Purdie deceased April 28th. 1779,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library.

- “Inventory of the Estate of William Rind,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 17, no. 1 (Jan. 1937): 55.

- See, for example, Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America, vol. 1 (Worcester: Isaiah Thomas, 1810), 334; David Waldstreicher, Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution (New York: Hill & Wang, 2004); Jonathan Senchyne, “Under Pressure: Reading Material Textuality in the Recovery of Early African American Print Work,” Arizona Quarterly 75 (Fall 2019): 109–32; Joseph Adelman, Revolutionary Networks (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019), 222; Justin Pope, “A Slave at the Press: Peter Fleet and Reports of Slave Unrest in the Boston Evening-Post, 1735–1758,” Slavery & Abolition 42, no. 4 (2021): 691–709.

- Earl G. Swem, “A Bibliography of Virginia: Part II,” Bulletin of the Virginia State Library 10, no. 1–4 (1917): 1064, 1064. See Jordan Wingate, “Enslaved Pressmen in the Southern Press,” American Periodicals 32 (no. 1, 2022): 49n5

- Thomas D. Morris, Southern slavery and the law, 1619–1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 343. William Waller Hening, ed., Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, From the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (Richmond: Franklin Press, 1819), 6:364

- John Waring to Benjamin Franklin, Jan. 24, 1757, in John C. Van Horne, ed., Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery: The American Correspondence of the Associates of Dr. Bray, 1717–1777 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 122.

- Heather Andrea Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 15–16, 208–9.

- See, for example, advertisements in the Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), March 28–April 4, 1766; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Apr. 4-18, 1766.

- Frank Lambert, “‘I Saw the Book Talk’: Slave Readings of the First Great Awakening,” Journal of African American History 87 (Winter 2002): 14, 17, 20–21; Charles F. Irons, Origins of Proslavery Christianity: White and Black Evangelicals in Colonial and Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 36–38, 41.

- For other examples, see Virginia Gazette (Rind), Oct. 26, 1769, page 3. Jordan E. Taylor, “Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade, 1704–1807,” Early American Studies 18, no. 3 (Summer 2020): 287–323.

- John J. Zaborney, Slaves for Hire: Renting Enslaved Laborers in Antebellum Virginia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 2012), 11–12.