While dressing Colonial Williamsburg’s interpretive staff is both exciting and rewarding, it also comes with a great deal of responsibility. Along with daily tasks of constructing and maintaining period-appropriate clothing, there is the obligation to ensure that the clothing presented is correct not only in fit, but accurately represents the dress of the 18th-century Williamsburg population.

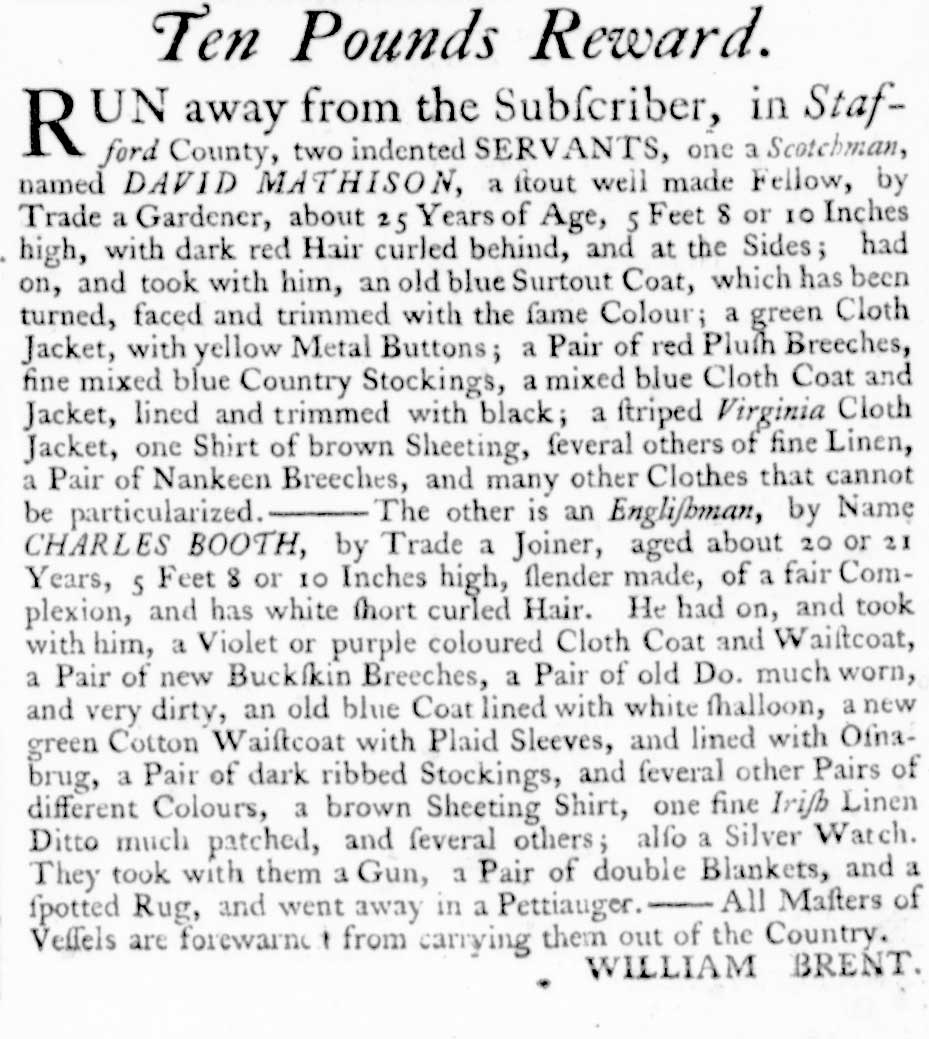

While most of the clothing seen on our museum’s streets is modeled after English fashions prevalent in this colony, it is important to illustrate the diverse population of colonial Virginia. Take Scottish dress and textiles, for example. Merchant’s ledger books, newspaper, and runaway advertisements show elements of Scottish or Highland dress such as tartan, plaid, and bonnets were worn with regularity in the colonies (see Virginia Gazette image below). The historic record also highlights that Scottish material culture was not only used by Scottish immigrants, but also by a diverse society in 18th-century British North America.

So what is the evidence of Scottish dress and textiles found in the American colonies? The answer to that question can only be found with an understanding of what is meant by Highland dress. Throughout the century, several travel narratives were written describing the inhabitants of Scotland, but one of the most vivid was written by Edmond Burt.

In one of his letters, Burt states that “Highland dress consists of a bonnet made of thrum without a brim, a short coat, waistcoat, longer by five or six inches, short stockings, and brogues or pumps without heels.” Burt continues, “over this habit they wear a plaid, which is three yeards long and two breadths wide, and the whole garb is made of chequered tartan, or plaiding.” This description dates to the 1730s and despite the fact that highland dress was outlawed for almost 40 years within the boundaries of Scotland, elements of the dress continued to be worn in Scotland and were prevalent in other parts of the British Empire for the rest of the century and beyond.

Tartan/Plaid

By far the most significant evidence of Scottish manufacture found in the American colonies were the yard goods, tartan and plaid. These textiles were most often made of woolen or worsted fibers but were also made of silk or a combination. They were very often twill woven and, in many cases, featured a crisscross pattern of lines that are woven into the textile to create patterns of a varying intricacy as Burt penned, “chequered tartan, or plaiding.” In Scotland, lengths of plaid were used by both men and women in the form of what is commonly called a man’s breacan or a woman’s arisaid. Both garments were lengths of material roughly three yards long and 54 inches wide, the former being an early version of the kilt and the latter being a combination shawl/cloak/veil (seen below).

While these garments are considered iconic Scottish dress, there is little evidence that they were used in America outside of the Highland regiments. Instead, tartan and plaid were used in the construction of a variety of garments found throughout the colonies. Because plaid and tartan were made in a variety of qualities, they could quite literally be found in anyone’s clothing inventory. There are abundant Virginia probate inventories listing either a banyan or wrapping gown made from these textiles. Those garments would have been similar to one housed in the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg collections, seen below.

Tartan and plaid were also used to make women’s gowns, jackets, and petticoats as well as men’s jackets, waistcoats, and breeches. Coarser variety of plaid and tartan were used to make clothing for the indentured and enslaved, though it is difficult to assess the clothing worn by these members of society since few examples still exist today.

Because of this scarcity, researchers must use a variety of methods to shine light on the clothing of the “lower sorts,” as they were termed in the 18th century. Visual records such as paintings, watercolors, and sketches are one way to not only see the clothes, but also how they were worn. The images that focus on depicting the enslaved and working class are rare, but that makes them even more worthy of consideration. The clothing seen in Dance and Music in Beaufort County (below) could be an example of the type of plaid that used in clothing the enslaved.

Runaway advertisements posted in colonial American newspapers help illuminate the material world of enslaved and indentured laborers. Beyond providing a physical description of the runaway, the advertisements generally describe the clothing that runaways were wearing and took with them. These sobering documents give researchers a much better understanding of the variety of the dress used in colonial America. Without them, history may have forgotten Stephen, an enslaved man, who in 1774 fled his captivity wearing “white plaid breeches [and a] blue plaid jacket.” Or that years earlier in 1746, a teenaged Highland servant boy, named John Ross ran away wearing a “Tartan Waistcoat without Sleeves, lin’d with green Shalloon.” Paul Sandby’s watercolor A Gillee Wet Feit (below) gives the viewer a sense of how John Ross’s waistcoat might have looked.

Bonnets

Sandby’s work also illustrates another element of Highland dress that was used well beyond the Scottish diaspora: the bonnet. Edmond Burt wrote that a highland bonnet was “made of thrum without a brim.” Using the term thrumbed, this quote indicates that that bonnets were knit and then heavily fulled making it almost watertight. Along with weather proofing, the fulling process would also make a bonnet very warm. Bonnets of this type were typically worn by men and boys in the 18th century and were seemingly referred to interchangeably as blue bonnets, Scot’s or Scotch bonnets, or Kilmarnock bonnets, the latter because Kilmarnock, a city in southwestern Scotland, is known for its knitting industry and bonnet production.

Along with having various descriptive names, these bonnets were produced in a variety of styles. Sandby’s A Gillee Wet Feit, illustrates a style of bonnet popular throughout the first three quarters of the 18th century, but was still being worn into the early 19th century. Another style that grew in popularity in the last half of the century and was worn by both civilians and the Highland regiments was commonly called a diced bonnet. It can be seen in the portrait of Major Patrick Campbell (below). Bonnets were sold in stores throughout the colonies and were used by a variety of people, both free and enslaved. Again, the runaway advertisements will provide evidence for the diverse use of this garment. For example, David, an enslaved man, in 1751 fled captivity wearing a “new Scotch Bonnet”.

Stockings

A common article of Scottish dress that is worn in the colonies in both military and civilian contexts were plaid stockings. These were cut out of a woolen plaid textile and sewn together to create the stockings, as opposed to knit stockings, which were the preferred style of stockings throughout most of the 18th century. It is probable that plaid was woven in the 18th century in both plain and patterned varieties and that stockings were created from both styles. The mid-century portrait of John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore (below) illustrates the style of plaid stockings used in the Highland regiments.

Some civilians also wore these, but the largest consumer of plaid stocking in 18th-century British North America were the enslaved. Plantation owners would annually order dozens of pairs of plaid stocking directly from merchants in Scotland, who would deliver them to private docks connected to the plantations. Additionally, merchants selling goods in the colonies would import them to be sold in their stores. One such merchant, John Glassford, owned several stores near Alexandria, Virginia. Between 1758 and 1765 Alexander Henderson, the manager of Glassford’s stores who was also a Scot, ordered 936 pairs to be sold out of stores he ran in northern Virginia.

In conclusion, research shows that Highland material culture was used throughout colonial society and in a variety of ways. In fact, this applies to every culture represented in colonial America.

While few guests have the opportunity to visit the Costume Design Center at Colonial Williamsburg, we are able to connect with them through the shared experience of clothing. Each day, people around the world put on clothes, just as they did during the 18th century. The Costume Design Center continues the important work of researching and representing the diversity of 18th-century Virginia dress for our guests.

Michael Ramsey is an Accessories Craftsperson in Colonial Williamsburg’s Costume Design Center. He has worked with the Foundation in several capacities starting in 2013. Along with his work at the Costume Design Center, Ramsey enjoys studying the history of American dress and textiles per-1840. He earned a bachelor’s degree in History from Austin Peay State University.

Further Reading

- Baumgarten, Linda, ‘Clothes for the People,’ Slave Clothing in Early Virginia’, Journal of Early Southern Decorative Art, vol. XIV, 1988, pp.27-70.

- Baumgarten, Linda, ‘Plains, Plaid and Cotton: Woolens for Slave Clothing’, Ars Textrina, vol. 15, 1991, 203-222.

- Burt, Edmund. Burt's Letters: From the North of Scotland. United Kingdom: Birlinn, 2017.

- Faiers, Jonathan, Tartan, Berg, Oxford, New York, 2008.

- Hamrick, Charles and Virginia, Virginia Merchants: Alexander Henderson, Factor for John Glassford at his Colchester Store, Fairfax County, Virginia, His Letter Book of 1758-1765, Iberian Publishing Company, Athens, Georgia, 1999.

- Ramsey, Michael, “Plaiding the People: Party-coloured Plaid and Its use in the Eighteenth-Century North American Colonies”, The Journal of Dress History, Volume 3, Issue 3, Fall 2019.

- Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Williamsburg, 14 November 1751, The Geography of Slavery in Virginia, University of Virginia, http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/gos/.

- Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), Williamsburg, 7 January 1775, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/.