My name is Emily Zimmerman and I’m a laboratory technician with Colonial Williamsburg’s Department of Archaeology. Part of my job has been to transcribe and interpret entries in the commonplace book, or CPB, of John Custis IV (1678-1749). In it, he recorded more than 180 medicinal remedies. Recently, I came across one remedy attributed to a “Doctor Pawpaw” in the CPB. A simple search for this doctor’s identity showed me bits and pieces of his story…but often using different variations of his name. I found that he was variously referred to as Taupan, Pagan, Pawpaw, Papaw, and Panpan. Let’s explore the life of the man Custis called Doctor PawPaw, and how he came to be associated with a disease known as Yaws. In this post, we’ll start by taking a look at the disease his remedy was said to cure.

A factsheet published by the World Health Organizations describes the conditions in which bacteria that cause yaws still thrives—and they sound eerily similar to the living conditions that many enslaved people were forced to endure: “it thrives in overcrowded communities, with limited access to basic amenities, such as water and sanitation, as well as health care.” The horrendous journey across the Atlantic left hundreds of slaves crammed into the damp lower decks of ships for anywhere from 21 to 90 days. They were denied access to the basic necessities for good sanitation, which made ideal breeding grounds for the disease. Although the climate of the colonial American south was milder than either Jamaica or Africa, the conditions were similar enough to the tropical regions where yaws is thought to have originated for the disease to proliferate.

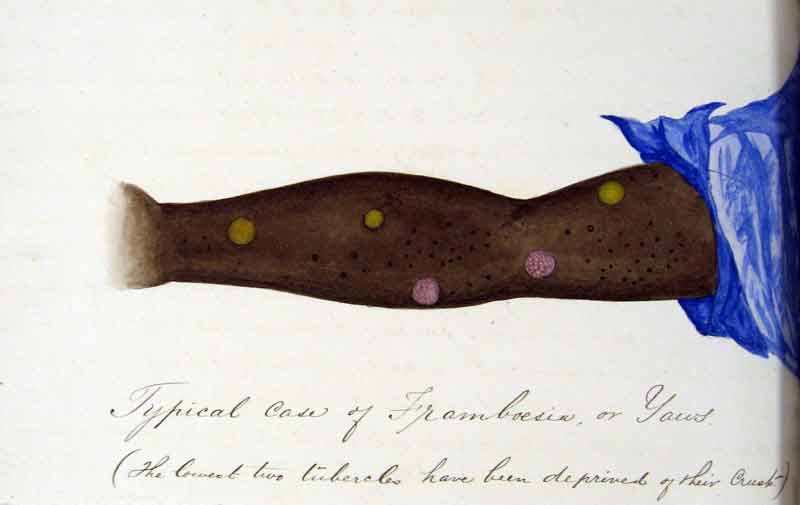

Yaws is transmitted through skin-to-skin contact and continues to proliferate in rural, tropical areas where sanitation facilities are difficult to access. A similar disease, syphilis, is caused by a closely related bacterium. Two types of syphilis, venereal syphilis and endemic syphilis, were likely present in the colonial American south long before yaws appeared in the colonies and exhibited lesions similar to those seen associated with yaws, making treatment and cures a confusing matter (Fig. 1). In fact, it was thought that any doctor basing his treatment on the physical appearance of the sufferer was apt to confuse any one of the diseases with the other two—and possibly administer improper treatment accordingly.

Two of the remedies in Custis’ CPB were meant to treat yaws, the first was attributed to Doctor Pawpaw. In the 18th century, many medical authorities are thought to have confused yaws with “the pox” or syphilis, and Custis may have been one of these people. Today, we know that both diseases are caused by similar bacteria, a cure for one might alleviate some symptoms of the others without offering an effective, permanent cure.

So far, the earliest mention I’ve found of yaws, comes from a 1679 text A Discourse of the State of Health in the Island of Jamaica, where it’s described as Jamaica’s “native disease.” Later, it was discovered that yaws also existed in west and central Africa, the primary export regions where Africans were captured and, eventually, enslaved in the Americas and the Caribbean.

While yaws primarily affected enslaved people, other members of American colonial society also appeared to have contracted the disease. In fact, John Custis IV is believed to have had yaws himself. In a 1742 letter, he reveals that he is suffering from an unknown disease he thinks he got while “endeavoring to cure” his slaves. He goes on to describe his observations of the disease, its symptoms, and his attempts at cures. He says…

“it kills no one; and wt is strange in perfect health…the first attack is bumps all over the body wch itch prodigiously…then these bumps break and run into soars Sometimes matter & corruption comes out; I have had some of my slaves all over like a galld horse back that they could neither sit ly or stand without a deal of misery, this holds them some a year or 2 some more with grievous pains all over them but more particularly the Joynts…I have tryd all manner of things I could think of for their relief and found mercuriall purges the best.”

The medicinal remedies recorded in Custis’ commonplace book include four that incorporate a mercurial ingredient (any ingredient with a high mercury content) to treat a ‘venereal disease.’ In two, quicksilver and mercurius dulcis are used in treating “y Itch” (scabies) and “A Gonorea or Clap.” Quicksilver is also used in “An ointment to cure y Yaws,” and Custis recommends that “mercurial purges ought to be taken” in addition to the ointment. These three instances highlight Custis’ apparent preference for using mercurials to treat venereal and skin diseases.

Custis was not alone in his use of mercurials against venereal disease. In his article, The “Country Distemper” in North Carolina, Thomas C. Parramore describes the use of mercury as an early cure for venereal syphilis along with its mixed success. Two amateur physicians practicing in the 18th century by the names of John Brickell and John Lawson, observed cases of yaws and syphilis in North Carolina. Both Brickell and Lawson tried using mercury as an ingredient in their remedies for the diseases. Lawson declared mercurial remedies to work on all three, while Brickell disagreed, he believed they rarely cured yaws. A third opinion held that the main difference between yaws and syphilis was that mercury worked for syphilis but never worked to cure yaws. This suggests that Custis or his slaves may have been sick with endemic syphilis rather than yaws since he so strongly believed mercurials worked best. Another piece of supporting evidence is that he recorded Dr. Pawpaw’s remedy prior to recording the one containing mercurial. The remedy uses a completely different group of ingredients but was acclaimed to be a great cure for yaws. In fact, the success of Dr. Paw Paw’s remedy would prove a life changer for him!

Stay tuned to learn more about Dr. Pawpaw and his remedy for yaws, coming to the blog soon.

Emily Zimmerman is an archaeology lab technician with the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeology. In addition to her work transcribing and researching the remedies recorded in the Commonplace Book of John Custis IV, Emily works tirelessly cataloguing the many artifacts uncovered at Custis Square.

Resources

- The American Revolution Project (2020) The Business of Freeing a Slave in Virginia. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Breslaw, Elaine G (2014) Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America, NYU Press.

- Brickell, John (1737) The Natural History of North Carolina, Johnson Publishing Company.

- Chappell, Gordon W. Ed. (2000) Southern Plant Lists, Southern Garden History Society, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Edwards-Ingram, Ywone (2005) Medicating Slavery: Motherhood, health care, and cultural practices in the African diaspora. College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences.

- McIlwaine, H.R. Ed. (1930) Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia Vol. IV, Virginia State Library, Richmond VA.

- Parish, Susan Scott (2012) American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World. UNC Press Books.

- Parramore, Thomas C. (1971) The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 48, No. 1, The “Country Distemper” In Colonial North Carolina. North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

- Paugh, Katherine (2014) Yaws, Syphilis, Sexuality, and the Circulation of Medical Knowledge in the British Caribbean and the Atlantic World. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 88 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Schiebinger, Londa (2017) Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, Stanford University Press.

- Taylor, Lyda Averill (1940) Plants Used as Curatives by Certain Southeastern Tribes, Botanical Museum of Harvard University, Cambridge MA

- World Health Organization (2019) Fact Sheet: Yaws, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Zuppan, Josephine Little Ed. (2005) The Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717-1742. Rowman & Littlefield.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital, plus, explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers to plan your visit.