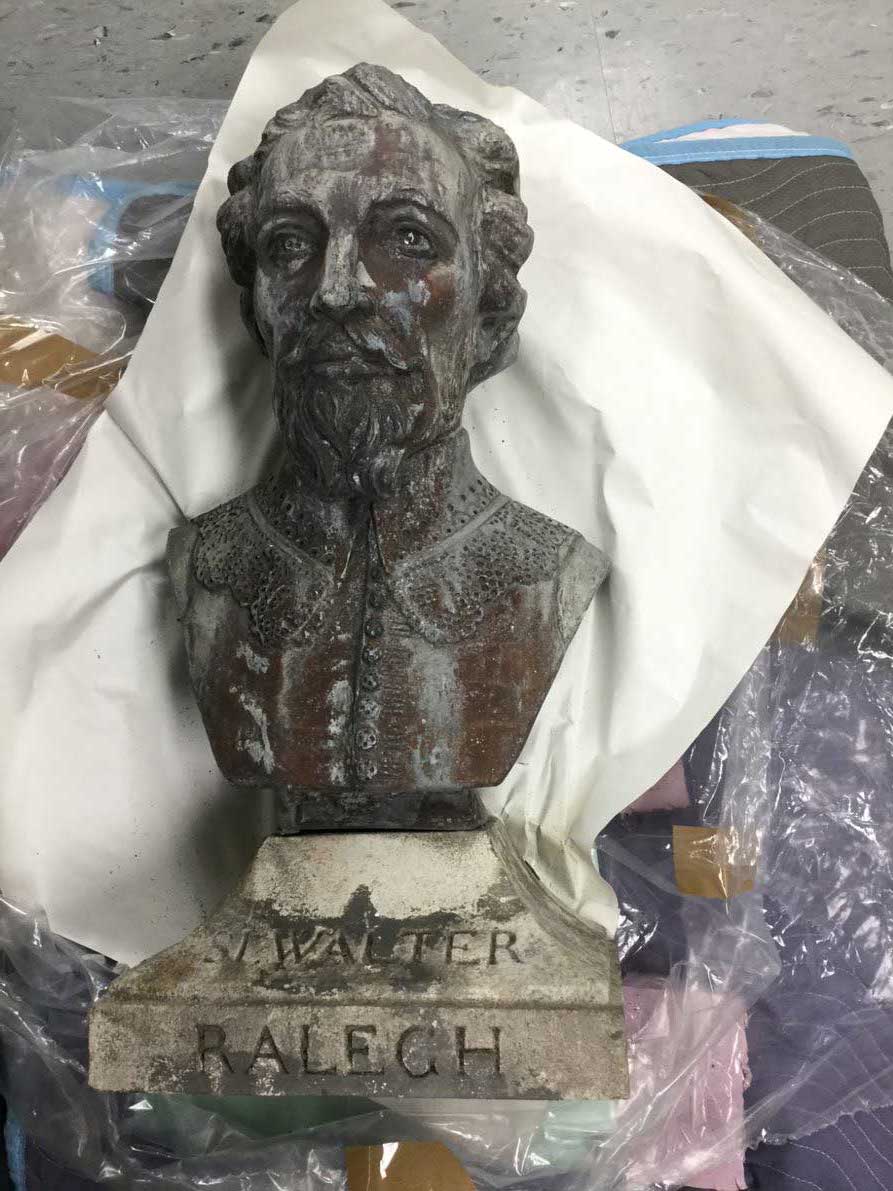

In 2017, a lead bust of Sir Walter Raleigh (Figure 1) was removed from the pediment above the front door of the Raleigh Tavern in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area prior to the addition of a porch. This gave conservators the opportunity to address the sculpture’s corrosion and structural damage issues.

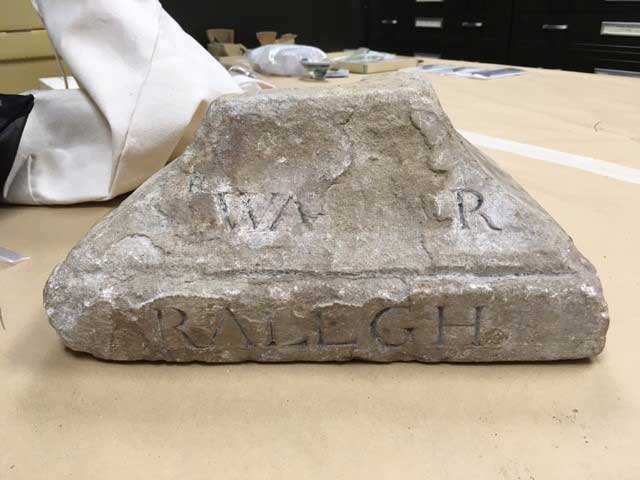

Though the Raleigh Tavern burned in 1859 and the fate of the original sculpture is unknown, historians believe that a similar metal bust of Raleigh was in place on the Raleigh Tavern pediment in the 18th century. The original ca. 1740 limestone base survives and is stored with Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeological collections (Figure 2).

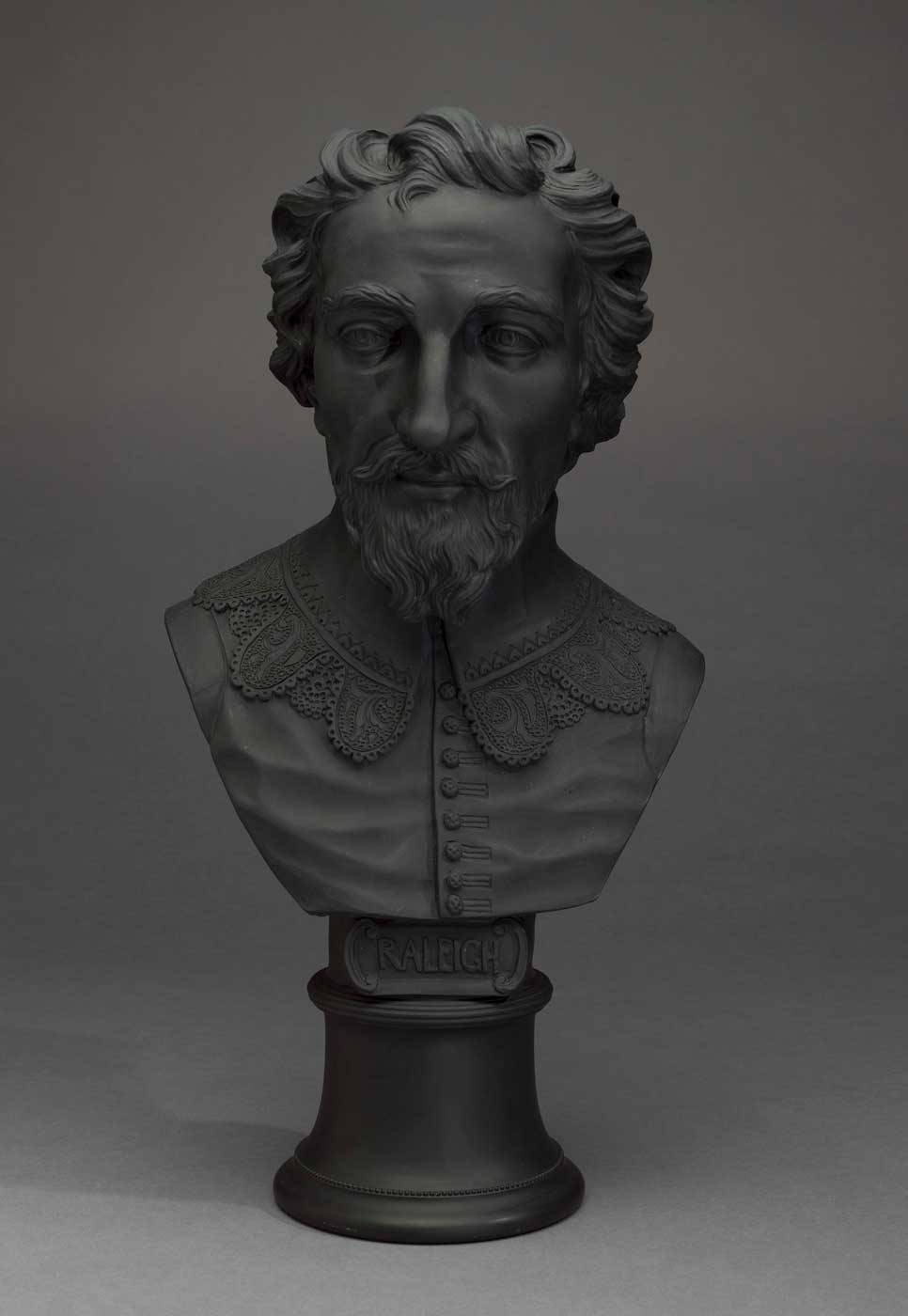

Colonial Williamsburg commissioned the lead reproduction sculpture in 1931 from Boston’s North Bennet Street Industrial School and modeled it on a black unglazed stoneware version in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection made by Harry Barnard of Wedgwood. To make the reproduction, Barnard repaired a damaged plaster mold originally made in the 18th century by Josiah Wedgwood to create the stoneware bust requested by Colonial Williamsburg in 1930 (Figure 3). The lead casting of the bust was enlarged by one third from the Wedgwood model to appropriately fit in the pediment of the Raleigh Tavern.

After the reproduction lead bust of Sir Walter Raleigh was removed from the Raleigh Tavern in 2017, it was taken for a condition examination to Colonial Williamsburg’s Objects Conservation Lab where Conservator of Objects Tina Gessler noted significant loss of material on the top of the bust. While corrosion can be an expected consequence of all metal sculptures displayed outdoors, this kind of structural damage evidenced is unique to lead sculpture. Rodents, such as squirrels, like the sweet taste of lead and often gnaw on outdoor sculpture. The loss of material on the Raleigh bust was significant with roughly 4 centimeters missing from the top of the sculpture (Figure 4).

The damage was deep enough to open a V-shaped casting seam on the top of the sculpture, which left the bust vulnerable to water ingress and at risk of accelerated corrosion from pooling of water on the interior of the sculpture. Several preservation-based options were considered to address the bust’s condition problems.

The first option was to use a 3-D scan of the stoneware bust to generate a reproduction metal bust. Dr. Bernard Means from Virginia Commonwealth University’s Virtual Curation Lab made a 3-D scan of the stoneware bust using Scan Studio Pro (Figure 5). However, it was determined that obtaining a full-sized metal 3-D print was not possible due to technology, size, and funding constraints.

The second option was to put the lead bust back on the building’s pediment after repairing the open seam on the head, cleaning the surface to address corrosion, and coating it with wax laced with cayenne pepper to deter further gnawing by rodents. Given that the object was heavy and posed safety concerns and that the cayenne pepper coating would need to be reapplied annually, this option was also rejected.

The third option was to take the lead bust to a foundry for reproduction, casting it in aluminum. Aluminum is much lighter than lead, does not have toxicity concerns, and weathers to look like lead. This option was selected and supported by donor funding.

After removing the 1931 lead bust from its base, it was transported to the B.A. Sunderlin Bellfoundry in Ruther Glen, Virginia, for reproduction in aluminum. At the foundry, the rodent damage loss was replaced using the 3-D scan as a model (Figure 6). Then, a two-piece silicone mold was made, followed by a lost-wax cast in aluminum casting alloy (Figure 7). The aluminum cast was then sand-blasted and patinated to resemble lead (Figure 8).

Sculptor Ray Cannetti created and carved a limestone base to match the dimensions and font of both the 18th century and 1930’s versions. The patina of the reproduction bust was further adjusted in the Objects Lab after the aluminum sculpture was delivered by the foundry (Figure 9). As the patination wears off, oxidation of the aluminum will create a weathered surface. After the new front porch was added to the Raleigh Tavern, the reproduction sculpture and base were installed on the pediment (Figure 10).

Do you want to see Sir Walter Raleigh? The aluminum bust is on continuous display on the pediment of the Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street. Check it out anytime you visit Colonial Williamsburg! The 18th century stone base, lead bust, and Wedgwood stoneware bust will be featured in the forthcoming architecture exhibition, Restoring Williamsburg, opening April 30 at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.