Eighteenth-century theories about the causes of disease, transmission, and prevention were based on the science of the time. Doctors were influenced by the Enlightenment and used observation, experience, and logical analysis to create methods to deal with disease and prevention.

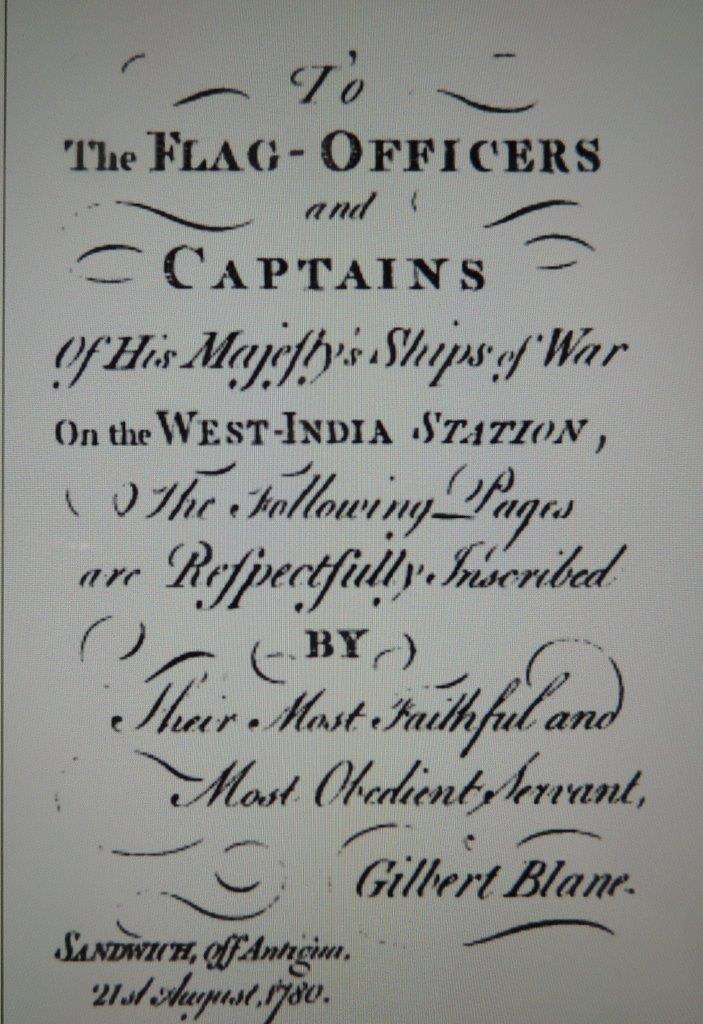

Dr. Gilbert Blane [1749-1834], wrote a series of books advising ship’s captains and officers about preventing disease and maintaining the health of those onboard ship. He is known for his efforts to reform British naval medicine and was employed as a physician to George IV.

This blog is dedicated to all our modern military, both active duty and retired. Some issues of shipboard life are timeless, such as staying healthy while traveling and living in close quarters, occupational health issues, and careful planning before leaving home port.

The next section features part of a packing list based on Blane’s advice when traveling to the Caribbean. The last section features pictures of Antiqua where Dr. Blane wrote his first book. In the 18th century, this Caribbean island was important to the British as a military base and had a dockyard for ship repair. The natural harbors surrounded by highlands created a refuge during hurricanes.

Packing List

Why do you think these items were considered important provisions for a successful deployment?

- Rosin and pitch

- Alum and cream of tartar

- A Tea kettle, boiler, gun barrel, and a barrel or mop

- Vinegar and camphor

- Tincture of Peruvian bark

- Preserved juice of lemons and oranges

- Soap

- Changes of clothing

- Shoes

Before one can appreciate the 18th-century efforts to fight disease, one needs to consider what was thought to cause it. In 1775, a medical dictionary defined contagion as: “The communicating or transferring a Disease from one Body to another, by certain Steams or Effluvia transmitted from the Body of a sick Person…sometimes a Distemper is conveyed by infected Cloathes [sic]…[there are some cases when] the Air is even said to be contagious, that is, full of contagious Particles.”

Blane observed that there were always some people that escaped disease when it was prevalent. He believed that people had different constitutions and the effects of disease depended on “peculiarities of constitution too obscure to be explained.” He also wrote that disease could be, “inhaled by the breath” or even absorbed by the skin.

Rationale for the above items:

- Rosin and pitch - One method of fumigating a ship to fight contagion was to create smoke and carry it about in a pot. The smoke should be created by sprinkling rosin or pitch on burning wood.

- Alum and cream of tartar were used to correct the bad taste of water.

- If one packed a tea kettle, boiler, gun barrel, and a barrel of water or a wet mop it was possible to make a still to make distilled water. Bad water was thought to cause disease.

- Vinegar and camphor- Vinegar was used to wash the sick berth. Caregivers in close proximity to patients were advised to smell camphor and vinegar. In general, the crew was advised to avoid close contact with the sick.

- Tincture of Peruvian bark- There are a variety of formulas for making this. In general, it contained cinchona bark also referred to as Peruvian bark and an alcohol base such as French brandy with a few other ingredients. Crews were encouraged to drink a half a wine glass of this before going ashore to prevent the intermittent fever. Intermittent fever was a good description for malaria. This South American tree bark was later discovered to contain quinine.

- Preserved juice of lemons and oranges- Blane recommends this to cure scurvy and mentions that he does not know how it works. Scurvy is a vitamin C deficiency. Vitamin C was discovered in the 1930s. There is additional advice on diet that this short blog precludes from featuring.

- Soap for washing clothes should be supplied and deducted from the crew’s wages.

- Changes of clothing- “The greatest evil connected with clothing is the infection generated by wearing it too long without shifting [changing]…. this case we have attributed to jail, hospital, or ship fever.” It was believed in the 18th century that another variable causing these illnesses was being confined in close quarters without access to fresh air. Today these conditions were most probably one type of typhus that is transmitted by lice.

- Shoes- Blane believed that next to scurvy and acute diseases, the ulcers from scratches on both the feet and legs were the most detrimental issue to a crew’s health, particularly for those working in the West Indies. He strongly urged that the crew should have shoes and be made to wear them, even when they protested and wanted to go barefoot in warm climates.

Additional advice by Blane for Captains and his officers:

- Provide a sick berth for contagious complaints.

- Keep the sick separated from the healthy, to prevent the spread of disease.

- Conditions are easier to treat at their onset. Someone should inspect the crew daily or at least every other day and to look for people that do not report for duty or appear to “droop or look ill.”

- Surgeons should be more respected.

- If you have to send any crew to a hospital, send their clothes and bedding with them, to get rid of all “seeds of infection.”

- If any crew member dies of a fever or flux [usually dysentery] dispose of their clothing by throwing it overboard.

- If a crew member recovers from the conditions, his clothing and bedding should be smoked and scrubbed.

Note the details on the bottom left of the page. The first version of this was only 27 pages long.

This is a modern picture of Antiqua featuring English Harbour in the foreground and Falmouth Harbour in the background. This is the Caribbean island Blane visited when writing his first book.

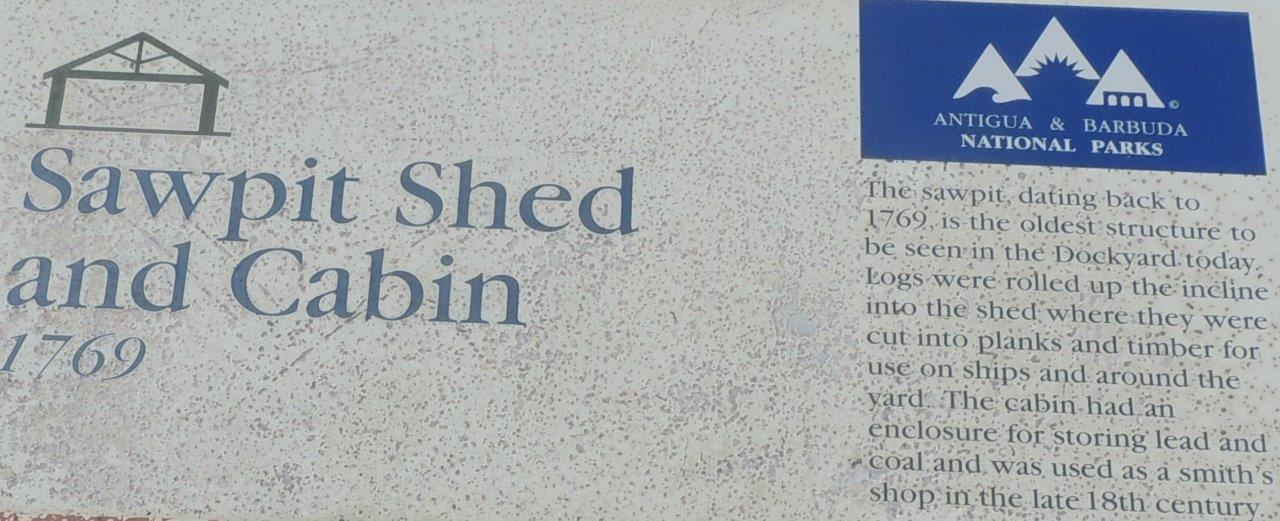

Today, the 18th-century dockyard, located at English Harbour, has been preserved as a museum. The oldest surviving structure dates to 1769 and is on the left. It was originally used as a sawpit. Logs were rolled up the stone ramp and cut to make timbers for use on ships and around the dockyard.

Details on the sawpit.

Notice the black and white capstans in the middle of the picture. Ropes were attached to the capstans and the ship. The capstans were used as winches to careen ships [pull a ship on its side] at the dockyard. The objective was to maneuver the ship on its side so that at low tide it was possible to perform maintenance and repair on the hull that was below the water line.

Robin Kipps is the supervisor of the Pasteur & Galt Apothecary. She has been studying and interpreting medical history for 37 years and has been working for the Foundation since 1981. Her interest in museums started at an early age. She grew up in a military family that traveled through 49 States and most of Canada. A fair amount of time was spent visiting historic sites, museums, and national parks. Some favorite aspects of her job include connecting the special interest of guests with some feature about medical history that could be personally relevant for them. She also enjoys working with 4th year pharmacy students. Two years ago, she and her team started teaching a 5-6-week course for colleges. Her hobbies include restoring and camping with her husband in their vintage travel trailer as well as embroidering and sewing. And yes, the sewing machine goes camping too!

Resources

Quincy, John. Lexicon Physico-Medicum 9th ed. (London: Printed for T. Longman, 1775), 99.

Blane, Gilbert. Observations On The Diseases of Seamen 2nd ed. (London: Printed by Joseph Cooper,1789), 293-4.

Blane, Gilbert. A Short Account Of The Most Effectual Means of Preserving The Health of Seamen. [London? 1780?], 19.