The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are home to a breathtaking range of folk and decorative art. Uncover the history behind beautiful objects in masterfully curated exhibitions in our series “Amazing Stories. Beautifully Told.”

Today we’re taking a close look at another painting on view in the Blagojevich Gallery. It’s part of an exhibition entitled “I made this…”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans, which was made possible through the generosity of The Americana Foundation.

What is it?

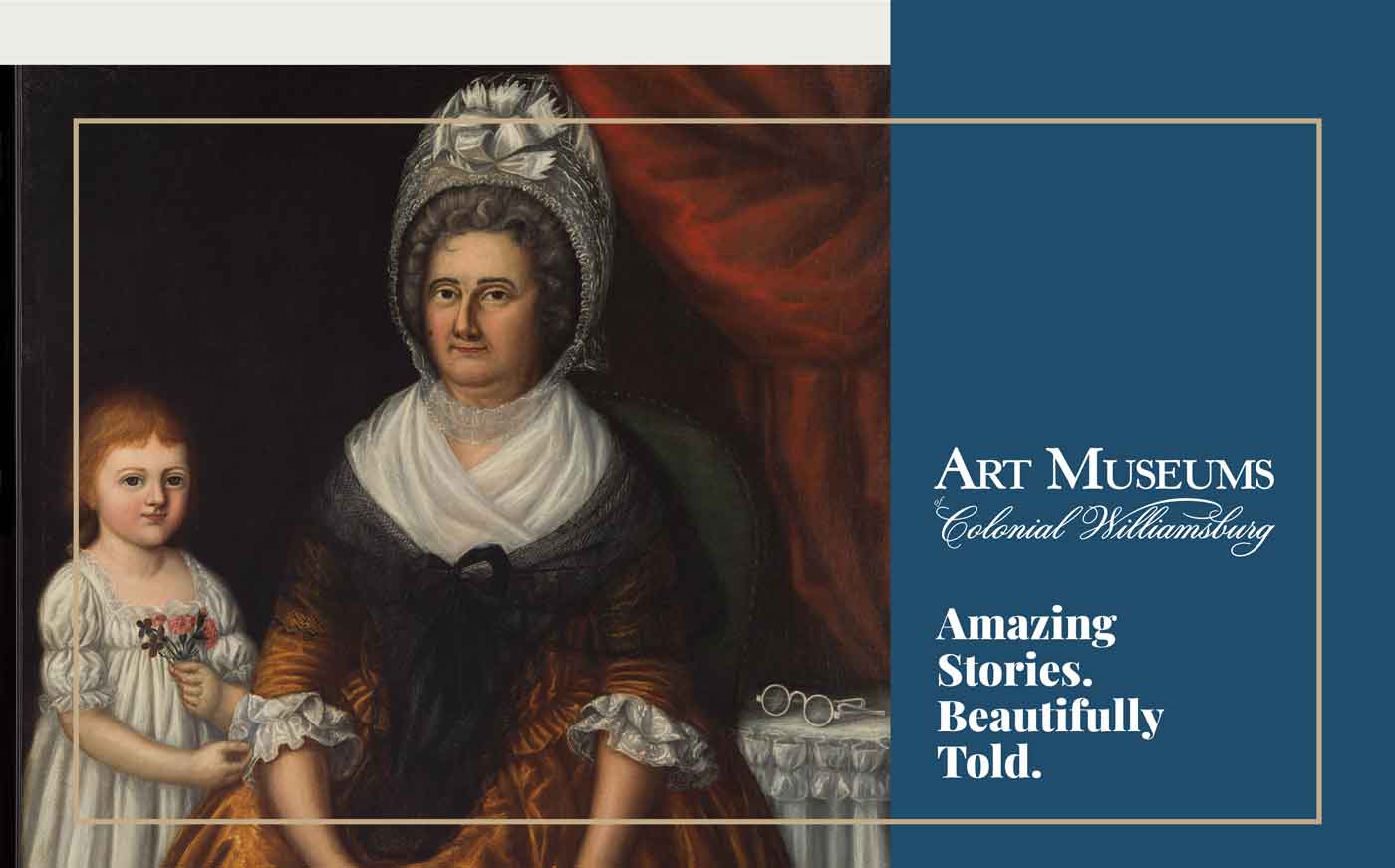

This remarkable ca. 1798 Portrait of Ellin North Moale (Mrs. John Moale) (1740-1825) and Her Granddaughter, Ellin North Moale (1794-1803) (Figure 1) is one of three paintings attributed to artist Joshua Johnson in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections. Johnson is one of the earliest professional free Black painters in America. His engaging composition of Ellin Moale and her granddaughter is believed to be among the artist’s earliest works. In addition, it is a somewhat larger, more complex composition, and more colorful than many of his other works. Most of Johnson’s commissions came from his Baltimore neighborhood. In addition to the neighborhood connection, he had another tie to the Moale family, which likely led to the commission of this double portrait. Officiating as Justice of the Peace, Mrs. Moale’s husband, John, presided over Johnson’s manumission from slavery in 1782. It is possible this meaningful connection elicited production of this complex and colorful double portrait relatively early in the artist’s career.

What’s the story?

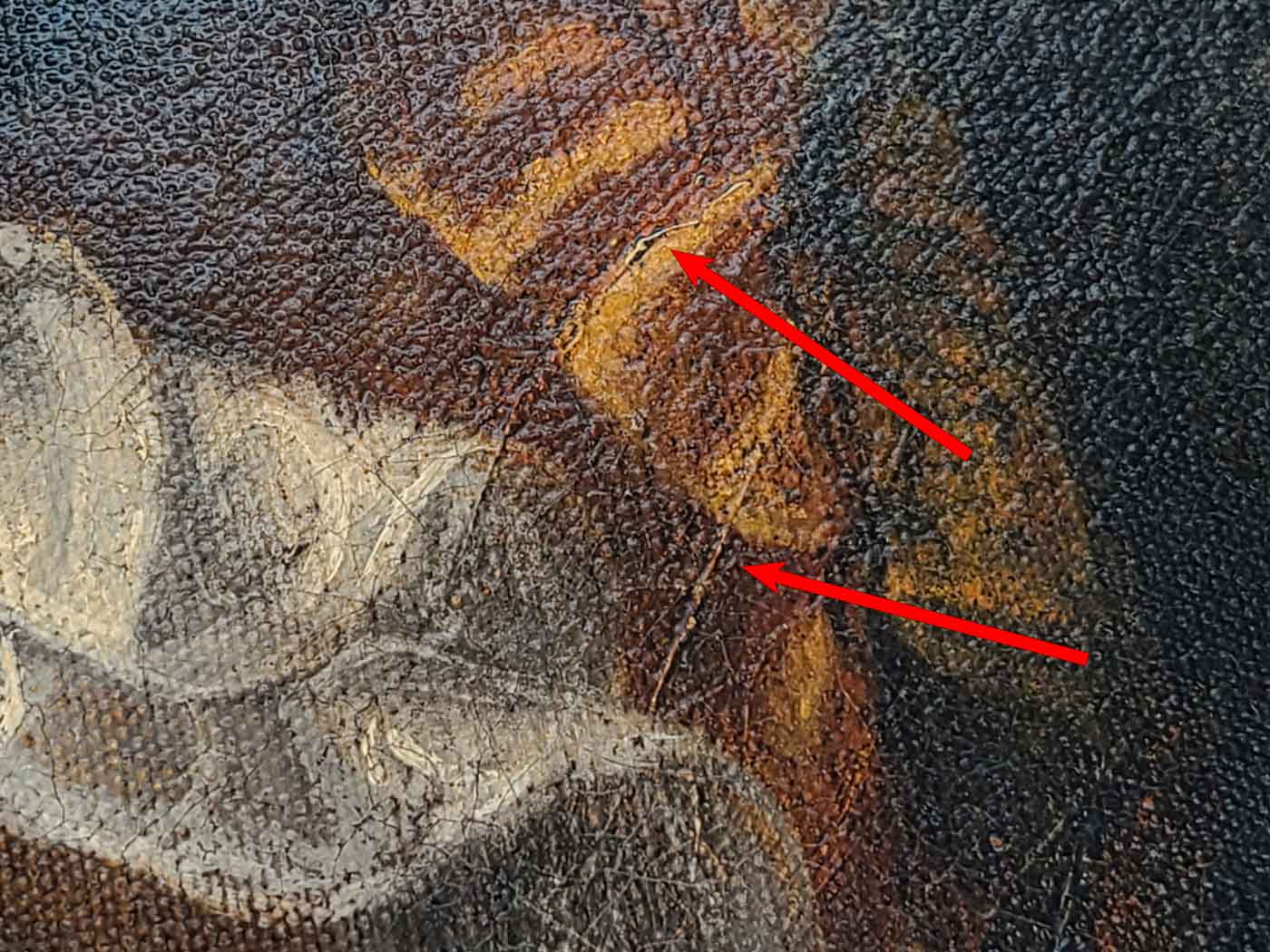

Preparing the artist’s paintings for exhibition provided an exciting opportunity to examine his work in the conservation lab and reveal the little-known materials and painting techniques of this artist (Figure 2). Taking a closer look invites a comparison with findings from the recent technical examination of the artist’s ca. 1805 Portrait of Mrs. Susanna McCausland and Child. Unlike the McCausland portrait, examination of the Moale portrait revealed no evidence of traditional underdrawing. To assist Johnson in his placement of the figures on the canvas, it is possible that he applied thick slashes of white impasto paint at key locations as a guide (Figure 3). This is a convention seen in some 18th-century American portraits.

X-ray images confirm the presence of these paint slashes. They also reveal a similarity in the artist’s working methods for the two double portraits. In both paintings he actively developed and refined his compositions on the canvas supports, shifting and adjusting edges and details as the paintings evolved. The more significant changes in the Moale portrait include modifications of the grandmother’s curls, the bonnet’s ribbon loops, the white kerchief (Figure 4), and the petticoat. In the boldly painted petticoat, major changes to the composition are easily visible in the x-rays.

While this new evidence shows that the artist created both compositions in an evolving manner on his canvases, the way he handled his paint varies between the two. While he rendered faces in the McCausland Portrait with opaque paints wet-on-wet blended, the face, arms, and hands of the grandmother in the Moale portrait have been largely modelled from transparent glazes. This is fairly unusual and is also seen in the copper-hued petticoat (Figure 5). It is possible Johnson observed this technique from one of the numerous artists working in Baltimore, though the artist described himself as self-taught.

Why it matters?

With so little known about Johnson, taking another close look at how he painted provides greater insight into his working methods and materials. The basic pigments found in the McCausland portrait are also found in the Moale portrait--lead white, charcoal black, vermillion, and red lakes--along with the addition of orpiment, a brilliant yellow hue. Mixtures with orpiment create both the copper hues of the jacket and petticoat along with the rich green of the chair upholstery. This new information adds to what we learned from the first portrait examined, further enriching our knowledge of painting materials available to the artist at that time. How did Johnson use these materials to paint? He began his composition by first working on a gray preparation layer, then sketchily placed some of the key elements of the composition using thick impasto strokes of white paint. Johnson then developed the sitters with his paint mixtures, sometime using rich glazing. And, as in the McCausland portrait, he dynamically changed and refined elements on his canvases as he painted. These clues provide us with a window into his skillful problem-solving abilities that turned his two-dimensional, blank canvas into a colorful three-dimensional space filled with beautifully rendered furnishings in addition to these sitters that touched his life in the period and can still touch our lives today.

See for yourself

For more information on this portrait painting as well as tens of thousands of objects in our collections online, visit: Portrait of Ellin North Moale (Mrs. John Moale) (1740-1825) and Her Granddaughter, Ellin North Moale (1794-1803). We also invite you to see this remarkable object in person at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg and discover more amazing stories, beautifully told.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.