As she boarded the Danger, a ship bound for Nova Scotia in November 1783, a fifty-three-year-old Black Loyalist woman paused to answer questions. A group of British and U.S. commissioners waited to question her, along with the other Black refugees boarding those ships.

Her name? Judith Jackson.

When did she escape slavery? 1779.

What was the name of her former enslaver? John Clain of Norfolk, Virginia.

What military department had she served? The Royal Artillery.1

The commissioners drafted Jackson’s response into a ledger known as The Book of Negroes, a voluminous document with the names and individual biographies of three thousand Black Loyalists who sought freedom behind British lines during the Revolutionary War. Judith Jackson’s entry is one of many in The Book of Negroes, but unlike some other Black Loyalists recorded there, we can trace many of the events that brought her name into the ledger. Her story of resistance and sacrifice illuminates the harrowing path that many Black Loyalists faced in seeking freedom during the American Revolution.

Judith Jackson Serves the British Military

Judith Jackson and her six-year-old child escaped their Norfolk enslaver in mid-May 1779. When Virginia’s last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, offered freedom to Black Virginians in late 1775, Norfolk had been in turmoil.2 Jackson and her child did not flee in the war’s opening moments. But four years later, when a British force raided Tidewater Virginia in May 1779, she took advantage of the opportunity and escaped.3

Before the war, enslaved women usually fled in larger groups, and accounted for less than fifteen percent of all runaways.4 Wartime raids provided Black women like Jackson the chance to escape their plantations and reach nearby British lines. As a result, the proportion of women running away from slavery doubled during the Revolutionary War.5 Jackson used the chaos created by the wartime raid to find refuge behind British lines along with over five hundred other Black loyalist refugee women, men, and children.6 British forces benefited from these escapes. They used Jackson and other Black Loyalist refugees to support the daily operations of British forces throughout the war.

After escaping Virginia, British officers put the new refugees to work when they arrived in British-occupied New York City. Military leaders assigned Jackson and the other Black Loyalists to work for wages, food, and accommodations for the rest of the war. Judith Jackson would serve the Royal Artillery Department. Over the next four years, Jackson was a personal servant in the Royal Artillery Department to multiple British officers and dignitaries, including Lord Dunmore. She served Dunmore in the Lowcountry South Carolina in late 1782 before returning with him to New York City.7

Refugee women like Jackson cooked meals and assisted the wives of officers. In a war where disease killed more people than bullets, laundresses like Jackson made a vital contribution by keeping military camps clean.8 In exchange for her labor, Jackson received money and clothes. She also developed a critical patronage relationship with Dunmore.

Though their army would have struggled without their work, the British did not always welcome Virginia’s Black women. A year after Jackson and her cohort of refugees reached New York City, the nearby British commander John Graves Simcoe ordered that only male runaways could “be protected by King George” as long as they arrived “without their wives and children,” who could not be “protected at present.”9 British General James Pattison complained about “not only the Male but Female Negroes with Children” escaping “into the City (which if they are suffered to do) they must become a burden to the Town.” 10

As a Virginian, Judith Jackson may have also encountered resentment. As one Black refugee recorded, the Loyalist mayor of New York David Mathews angrily exclaimed: “it was a Pity that all we Black folk that Came from Virginia was Not Sent home to Our Masters.”11 Jackson labored in an environment hostile to her identities. Although Black loyalist women like Jackson found refuge and wage labor with the British, they confronted additional burdens to sanctuary. Some white leaders believed that women and children were draining precious resources and contributing less meaningfully to the war effort than Black Loyalist men.

British Peace and Black Anxiety

While serving Dunmore in the Lowcountry, Jackson would have learned about the Crown’s disastrous defeat at the Battle of Yorktown, which signaled the war's end. What did a British defeat mean?

An answer came when she returned with Dunmore to New York City in late 1782. For Black Loyalists, the Treaty of Paris ending the war contained one especially important clause on the fate of fugitive slaves. As they discovered in the Spring of 1783, article seven of the treaty stated that the British would depart “with all convenient Speed, and without causing any Destruction, or carrying away any Negroes.”12 Would the British renege on their previous offers of refuge and freedom? Black Loyalist Virginians had experience with British officials renouncing earlier pledges of refuge. In 1778, Captain Benjamin Caldwell of the Royal Navy had turned away approximately four hundred runaways seeking refuge aboard Caldwell’s ships off the coast of the Rappahannock River.13 With peace looming over the New York garrison, Black Loyalist refugees pondered if the British would again turn their backs on them.

It soon became clear that the British military would only protect refugees who could prove they had lived behind British lines for a year or more. Sir Guy Carleton, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, directed the army to help enslavers who claimed to own a fugitive slave within the garrison. British and American commissioners would monitor ships bound for Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, Germany, England, and Jamaica.14

Enslavers wasted little time rushing into the city in response to Carleton’s invitation. Hessian Commander Carl Leopold Baurmeister observed, “almost five thousand persons . . . come into this city to take possession again of their property.”15 Boston King, a Black refugee from South Carolina, heard rumors of “masters coming from Virginia, North-Carolina, and other parts, and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New-York, or even dragging them out of their beds.”16 The provisional Treaty of Paris remade New York City into the central site for slaveholders to express their grievances. In the process, the treaty also transformed Black Loyalists’ most consistent site of sanctuary during the war into a site of re-enslavement and terror.

In early August 1783, Judith Jackson experienced this terror firsthand. Jonathan Eilbeck, a white Loyalist Virginian, forced Jackson and her child off their ship, which awaited departure for Nova Scotia. Per Carleton’s directive, Eilbeck claimed that he now owned Jackson and her ten-year-old after he purchased them from her former enslaver, and his brother-in-law, John MacLean in London.17 A Board of Inquiry, made up of British and American commissioners, reviewed Jackson’s case and nine others like it from May to August in Manhattan’s Fraunces Tavern.18

Black women like Jackson confronted the possibilities of capture and re-enslavement more than any other group, despite accounting for only a third of all Black Loyalists. Police took eight women and girls off their docked ships, most of whom left one or more child behind in their boat. Four of the women confronted in these cases by white claimants hailed from Virginia.19 Black women and children searching for refuge and freedom not only encountered greater hostility to their presence in the garrison but also confronted greater scrutiny than Black men in Board of Inquiry tribunals.

Eilbeck endangered the freedom Jackson earned through four years working for the British army, washing and ironing for Lord Dunmore. She disputed Eilbeck’s claim by detailing when she escaped, who she served, and where Jackson’s labor for the British took her. Jackson also shared another piece of important information with the commissioners. Two months earlier, she had received a passport certificate to leave New York from General Samuel Birch, commandant of the city. Commandant Birch provided passes to Black loyalists whom he deemed worthy of protection and passage to Nova Scotia. Ultimately, the Board of Inquiry decided not to adjudicate Eilbeck’s case because, as a Loyalist, his claim needed to move further up the chain of command to the commandant and commander-in-chief.

Unfortunately for Jackson, taking extra time to adjudicate Eilbeck’s claim proved disastrous. While awaiting the decision, Jackson petitioned Carleton on September 18, 1783. Since her last court appearance, Jackson informed Carleton, Eilbeck had gone rogue and attempted to abduct her and return her to Virginia before the British forces decided her fate. Jackson told Eilbeck, “I would not go with him.” Although Eilbeck did not abduct Jackson, he “stole my child and Sent it to Virginia,” removed “all my cloaths which his Majesty gave me,” stole the money she earned within British lines, and promised to hang a British officer for giving Jackson a passport certificate.20 Judith Jackson earned money, clothes, and shelter in exchange for her service, but Eilbeck wanted to deprive Jackson of her child and her belongings. Jackson believed her service to the Crown should have protected her family from marauding slave traffickers like Eilbeck. Carleton disagreed. Two days later, he decided that Eilbeck was Jackson’s rightful owner.

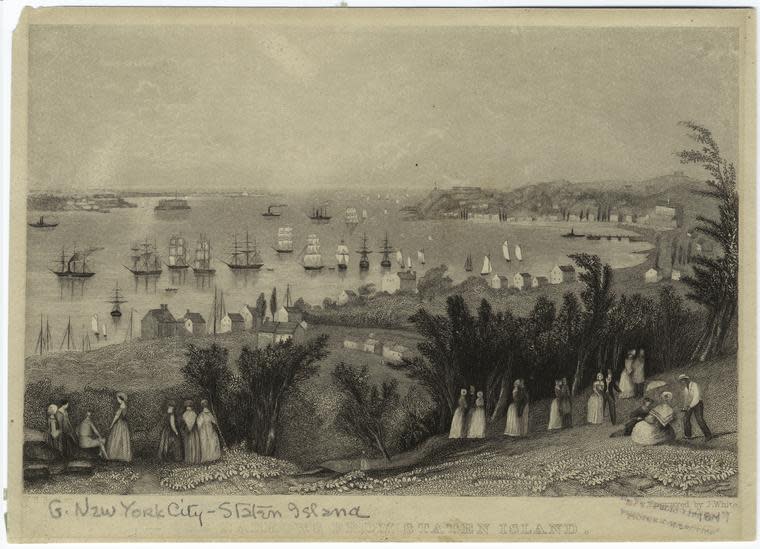

The court’s judgment should have ended Jackson's search for freedom. But instead, at some point after the formal conclusion of her case, Judith Jackson's fortunes changed. We don’t know exactly what happened. But according to the Book of Negroes, Jackson set off aboard the final set of ships departing Manhattan on November 30, 1783. She left aboard the ship Danger, bound for Nova Scotia, without her child. Jackson's freedom came at a high cost. We cannot know or understand what she felt as she took her seat aboard the Danger without her child, as the ship finally set sail off the coast of Staten Island into the Atlantic Ocean. She had attained freedom for herself but had lost her child. We know that a year later Jackson headed a household in Birchtown, Nova Scotia, but we know little about what happened to her next.21 We do know that Nova Scotia proved challenging for many Black Loyalists. How did Jackson feel as she reflected on her own road to freedom? She had endangered herself and labored for years for the comfort of British officers. Yet when she most needed the British army to provide security and protection, they were unable or unwilling to do so.

Author Bio: Adam Xavier McNeil is a Ph.D. Candidate in Early African American Women’s History at Rutgers University. McNeil is currently a Consortium Fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, where he is completing his dissertation, “Contested Liberty: Black Women & the Shadow of Re-Enslavement and Displacement in Revolutionary Virginia.”

Sources

Cover image of “Book of Negroes,” Courtesy of Nova Scotia Archives.

- Graham Russell Hodges, ed., The Book of Negroes: African Americans in Exile After the American Revolution (New York: Fordham University Press, 2021), 197.

- “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation,” Museum of the American Revolution.

- Sylvia Frey, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 149-151.

- Karen Cook Bell, Running from Bondage: Enslaved Women and Their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 9.

- Hodges, ed., Book of Negroes, L.

- “Return of persons whom came off from Virginia with General Mathew in the Fleet the 24th May 1779,” British Headquarters Papers, Public Records Office (PRO) 30/55/95, ff 10235.

- “Judith Jackson’s Petition to Sir Guy Carleton,” PRO 30/55/95, folio 9158.

- Elizabeth A. Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 4–6.

- General Orders December 2, 1780, John Graves Simcoe Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

- James Pattison to Abraham Cuyler, May 25, 1780 (New York: New York Historical Society Collections, 1875), 8:397. Link.

- Judea Moore to General Sir Henry Clinton, February 10, 1779, 52:25, Henry Clinton Papers, William L. Clements Library.

- Provisional Articles, Signed at Paris, the 30th of November, 1782, by the Commissioner of His Britannic Majesty, and the Commissioners of the United States of America (United Kingdom: T. Harrison and S. Brooke, 1783).

- Captain Benjamin Caldwell, R.N. to Governor Patrick Henry, January 13, 1778, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 11, p. 110-111.

- Royal Gazette (Rivington), April 18, 1783.

- Carl Leopold Baurmeister, Revolution in America - Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, ed. Bernhard A. Uhlendorf (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1957), 556.

- Boston King, “Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, A Black Preacher. Written by Himself, during his Residence at Kingswood School,”The Methodist Magazine (March-June 1798), 157.

- Norfolk County (Va.), Chancery Causes, 1718-1938, Heirs of Thomas Talbot vs. Executors of Thomas Talbot, 1778, 002, Local Government Records Collection, Norfolk County Court Records, The Library of Virginia (Richmond, Virginia). This case reveals meaningful familial connections between Jackson's enslaver, John MacLean, and Jonathan Eilbeck. Two of Thomas Talbot’s daughters, Suckie (Talbot) Maclean and Mary (Talbot) Eilbeck, married John MacLean and Jonathan Eilbeck.

- Minutes of the Board of Commissioners for Superintending Embarkations, May 30 to August 7, 1783, PRO 30/55/100 f. 10427, p. 3–15.

- Black Virginian women’s proportion of refugees claimed by enslavers nearly matches the percentage of Black women in the Book of Negroes.

- “Judith Jackson’s Petition to Sir Guy Carleton,” September 18, 1783, PRO 30/55/81/95 ff. 9158, DLAR-APS.

- Judith Jackson’s Entry, Muster Book of Free Blacks in the Settlement of Birchtown, Library and Archives of Canada.