The Story of Elizabeth Hayes

If you’re inclined to buy the old adage that “behind every great man is a great woman,” then you should know the name Elizabeth Hayes. For 18 years she was the personal secretary to Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, the “father of Colonial Williamsburg”—and like so many other women who toiled out of the limelight, her contributions to making the dream of Colonial Williamsburg a reality deserve more attention. And we have the records to prove it.

Elizabeth Hayes was born in 1898 and raised in Canandaigua, New York. She met Dr. Goodwin in 1921 when he was rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Rochester, New York. She had graduated the prior year from the Rochester Business Institute and was hired on for general secretarial duties and to assist Dr. Goodwin with a history he was writing of the Virginia Theological Seminary. “If I had known at the time the importance of the years that lay ahead,” she later said, “I would have commenced a diary at the very first meeting.”

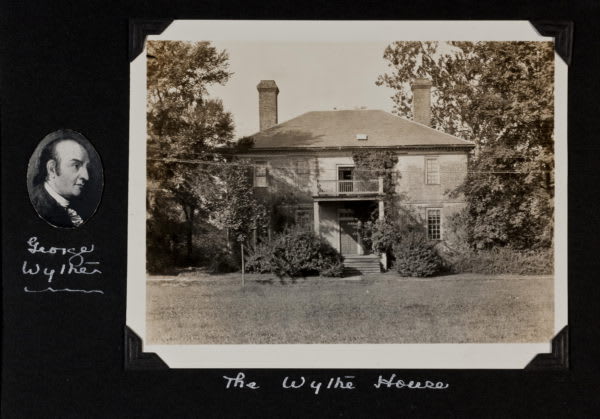

When Goodwin accepted a job directing the College of William & Mary’s endowment campaign in 1923, Hayes moved south with him. In addition to running his office and handling his correspondence, schedule, and seminary history, Hayes assisted with college fundraising, classes Goodwin taught at William & Mary, Goodwin’s restoration of the Wythe House in 1926-1927 after he again became rector of Bruton Parish, and any number of special projects. “The very moment Dr. Goodwin completed one absorbing undertaking, he had several more in mind on which to commence work at once—the same day! That is one reason why my work continued to hold interest and never grew tiresome.”

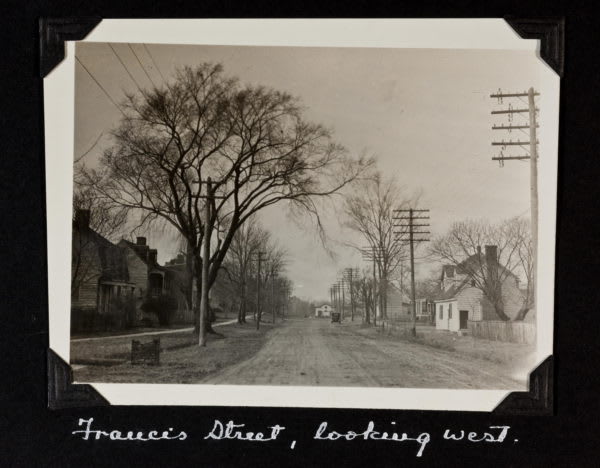

This was Goodwin’s second stint in Williamsburg. His tenure as the young rector of Bruton Parish Church had ended in 1909. To his distress, he found that during the intervening fourteen years, modern times had arrived in Williamsburg in the form of telegraph poles and gasoline stations. As they walked Duke of Gloucester Street together, Hayes described Goodwin having “visions, I believe, of another day and he talked only of the colonial past.” When Goodwin hatched his scheme to approach wealthy philanthropists to fund his goal of restoring Williamsburg to its colonial appearance, Hayes was by his side, working to help him realize his dream.

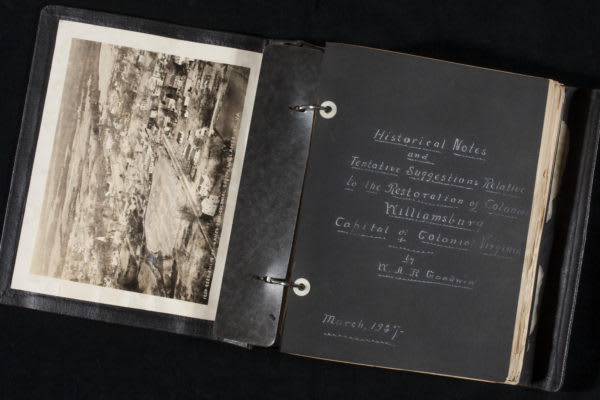

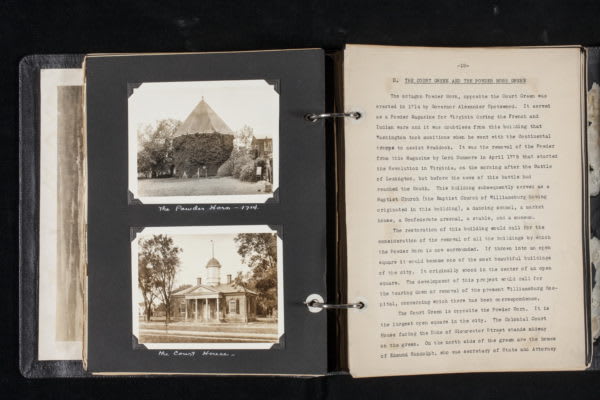

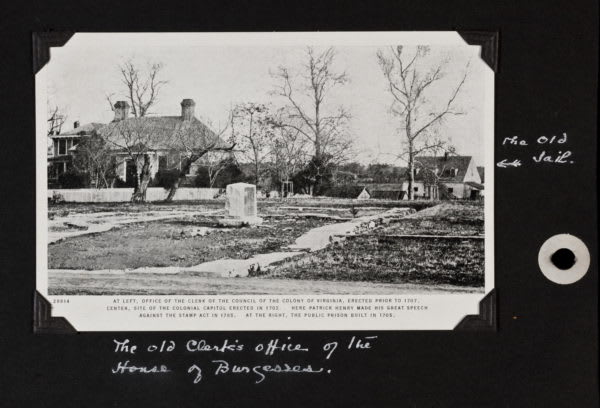

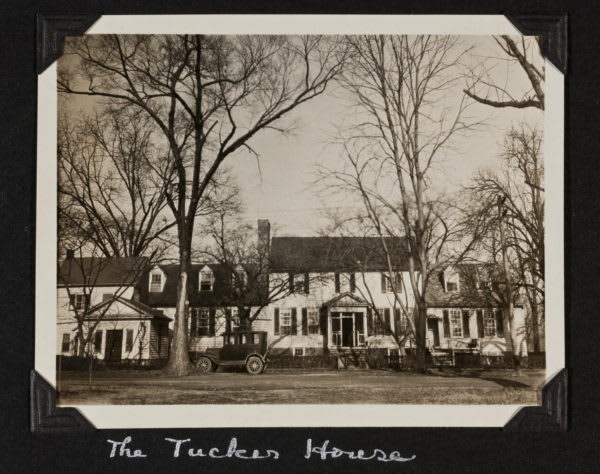

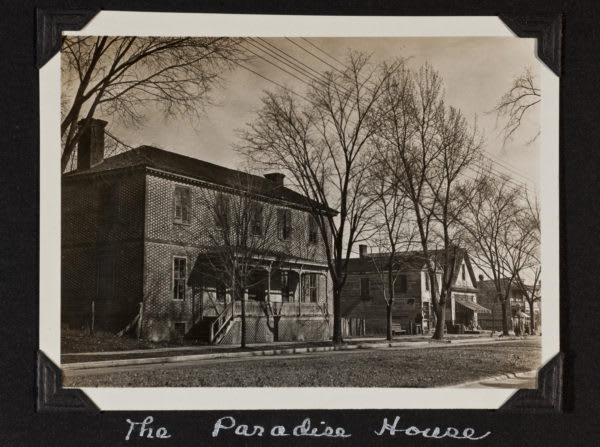

The most important pre-Restoration project that Hayes undertook was to create a notebook documenting the history of Williamsburg and its historic houses. She took the photographs and did much of the research herself, spending part of her 1926 Christmas vacation poring over old Virginia Gazettes. The Hayes Notebook, as it is known today, was a centerpiece of Goodwin’s May 1927 bid to convince John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to fund the Restoration.

Rockefeller took the notebook with him back to New York after the meeting to further ponder Goodwin’s proposal. He later wrote to Hayes saying it was “not only a most interesting volume, but one of the utmost helpfulness and importance in the consideration of the problems which are under review. The amount of time, thought, and painstaking effort which has been put into this book is enormous. It represents not only much patience, but profound interest in the subject under consideration.”

Goodwin’s (and Hayes’s) painstaking plans and presentation were a success—Mr. Rockefeller was on board

Hayes was one of the few in on the secret before Rockefeller’s role as the plan’s financial backer was made public in June 1928. She continued to do research and submit reports necessary for Restoration planning. Until 1928, she single-handedly kept the Restoration’s books as properties were acquired and plans formulated. She conducted tours of Williamsburg, wrote articles about the Restoration, helped fundraise for the Bruton Parish church restoration, and organized Goodwin’s professional and personal life.

Hayes and Goodwin stayed with the Restoration until 1935. In a speech made to the citizens of Williamsburg on the occasion of his retirement, Goodwin devoted two pages of description to the crushing workload of the early Restoration, thanking Hayes for her “devoted and invaluable service.” As Colonial Williamsburg President Kenneth Chorley wrote to Hayes in a June 1960 letter, “you of all people shared more closely than anyone else with Dr. Goodwin his hopes and aspirations for the restoration.”

In addition to the notebook made to help persuade Mr. Rockefeller, Hayes was responsible for two more of the most important documents in the Foundation’s archives. The first is the typescript with the amazing title The Background and Beginnings of the Restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia Compiled from Dr. Goodwin’s Files and from her Contemporaneous diary notes; by Elizabeth Hayes, Secretary to Dr. Goodwin.

Written in 1933, it is still the authoritative account of the earliest years of the Restoration, covering the years 1927-1928. Hayes had always recognized the importance of documenting the Restoration and had carefully taken notes and preserved correspondence. At 250 pages, the document gathers into one place a narrative and copies of correspondence that vividly recount the enormity of the undertaking. She had tried to explain, as she stated in a letter to Mr. Rockefeller, the spirit in which the Restoration was undertaken and the true facts related to its beginning.

The second document is the oral history she completed in 1957 titled A Memory Sketch of Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin in which she chronicled their early years together, information about his family life, and her pre-Restoration time in Williamsburg with observations about the college, the town, Bruton Parish Church, and the people that she knew there. Hayes’s history paints a delightful portrait of a people and a town in transition. Goodwin’s niece wrote to Hayes after reading the sketch, “Frankly, Elizabeth, I don’t know when I have enjoyed anything so much as reading your recollections….It was beautifully written and made Uncle Will so alive that I could almost smell the pipe smoke.”

Hayes remained employed by Goodwin until his death in 1939. Hayes then worked for several years as the social secretary for socialite and philanthropist Minnie Astor.

In 1943, Hayes married U.S. Air Force Colonel George W. Goddard. The next year they welcomed a daughter, Diane. She followed her husband and his work from Ohio to France, finally settling in Maryland after Goddard retired in 1953. The couple moved to Florida in 1970 and Hayes died in 1984. She is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

As you stroll through Colonial Williamsburg today, take a moment to think of Elizabeth Hayes and how her work touched every aspect of the Restoration’s early years. She was Dr. Goodwin’s sole employee during the formation of the idea of Colonial Williamsburg and worked hard to ensure its early success. Her professional skills were so valued that the Restoration paid her salary from 1927 to 1935, although she was technically Goodwin’s private secretary. All of her work for the Restoration was done in addition to work performed in support of Dr. Goodwin’s other personal and professional interests.

She may not have been the dreamer of big dreams or the philanthropist who could fund those dreams, and she may have been just a secretary, but she was an unfailing support and a tireless worker who was genuinely interested in her work. Without her,the Restoration would certainly have looked very different.

Thanks to the generous donation of John Elmore, the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library Corporate Archives Collection will be able to provide much needed conservation work to the Hayes notebook that helped convince Mr. Rockefeller to fund the Restoration. We thank Mr. Elmore for his assistance in preserving this archival treasure.

Sarah Nerney is an associate archivist in the Corporate Archives and Records department of the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. Her favorite things about the Foundation – which she joined in 2015 – are the oxen, the landscape crew (who can always answer a plant question), stalking the lambs in the spring, and the American Indian interpreters. In her spare time, Sarah likes to lovingly kill houseplants, read mysteries, hang out with her cats, and watch movies in which people with accents wear a selection of amazing hats.