The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are home to a breathtaking range of folk and decorative art. Uncover the history behind beautiful objects in masterfully curated exhibitions in our series “Amazing Stories. Beautifully Told.”

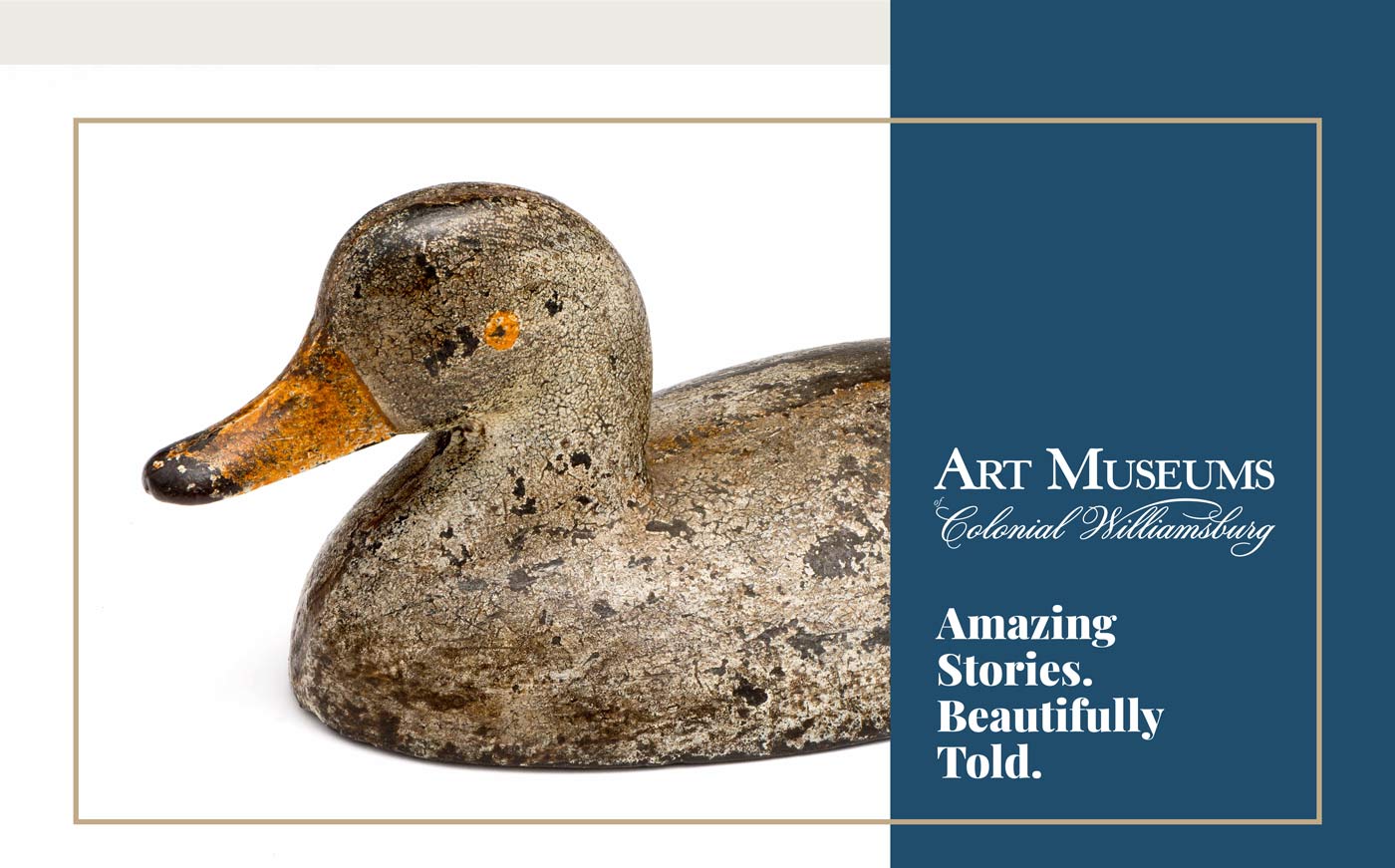

Today we’re looking at a highly unusual and rare duck decoy on view in the Clark Gallery. It’s part of an exhibition entitled “From Forge and Furnace: A Celebration of Early American Iron,” made possible through major support from Bonnie and Ken Shockey (the Paul K. and Anna E. Shockey Family Foundation). Additional support was provided by Virginia J. Repas in memory of her husband, Paul Repas.

What is it?

A life-size, cast-iron version of the top part of a duck, painted white and yellow to resemble an American Pekin duck, 1880-1910.

What’s the story?

Last I checked, iron does not float, so initially I was amused to see a duck decoy cast in this very heavy metal. The purpose of water-fowling decoys is to mimic real birds and fool them into flying within the hunter’s range, so I wondered how an iron duck could be successful. In fact, it was too successful!

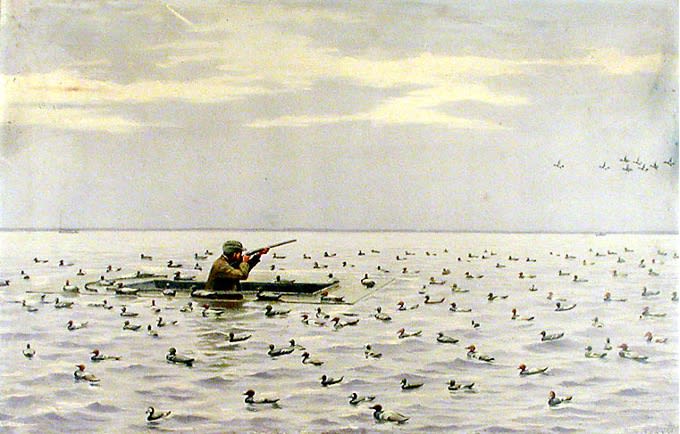

Until outlawed in the vast majority of the United States in 1918, iron decoys were used for "sink box" hunting. This method required the hunter to be hidden in a watertight box sunk to its top and set some distance offshore. Projections called "wings" were attached to the top of the box on all sides and were weighted down with enough painted iron decoys to sink it to the waterline, making the box and its occupant invisible to the intended quarry.

This highly effective method allowed for dozens, if not hundreds, of birds to be shot at a time, making it a perfect strategy for those supplying duck meat to the food market. Recognizing the great threat sink box hunting posed to hunted species of waterfowl like ducks and geese, Federal and local governments put a decisive end to it. Today, sink box hunting is legal by permit only in the North Carolina’s Dare and Hyde Counties.

While this decoy started out as a weight for sink box hunting, its paint scheme suggests otherwise. A white body and a yellow beak identify it as an American Pekin, a common domestic duck known to bond with humans. Whether raised for meat and eggs or kept as a pet, these ducks weren't wild, and wouldn't have been the target of a hunter's lure. After sink box hunting was declared illegal, perhaps it was transformed into a useful household fixture, much like the affable duck it mimics.

Colonial Williamsburg’s iron duck was collected by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and given to the Foundation in 1931. It was purportedly found in Ephrata, Pennsylvania.

See for yourself

For more information on this decoy as well as tens of thousands of objects in our collections online, click here. We also invite you to see this remarkable object in person at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg and discover more amazing stories, beautifully told.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.