An exploration into the 18th-century belief in extraterrestrial life

Standing amidst the swirling wind and beaming light of an alien spaceship, onlookers watch in awe as a space alien places his finger on Thomas Jefferson’s forehead and utters words that have become immortalized in history: “I’ll be right here.” It’s the tried and true conclusion of a classic story about a red-haired boy and his, um, intergalactic best friend who gets stranded on Earth, catches the eye of the US Government, and makes a dazzling escape through a slew of FBI agents aggressively holding walkie-talkies. The 18th-century was crazy, y’all.

Ahem.

Okay, fine. There were no walkie-talkies in the 18th-century. Nor was there an FBI, or CGI, for that matter. And I may have liberally borrowed (stolen) the above sequence from Steven Spielberg’s 1982 blockbuster, “E.T.” That said, this classic scene, as a whole, would not be as foreign to the 18th-century mind as we might think. Oftentimes, we consider Science Fiction — specifically, the belief in extraterrestrial life — as a thoroughly modern concept, but, on this National Alien Day, I submit to you, that 18th-century people widely believed in space aliens, or as they referred to them, “Inhabitants,” and, even further, used science, reason, and religion to defend their existence.

Take the below quip from Bernard Le Bovier, M. de Fontenelle’s 1686 book, Conversations On The Plurality Of Worlds, for example:

“For my part… I believe that since a prodigious company of men who have been, and still are, such fools to adore the moon, there certainly are people on the moon who worship the earth, and we really are upon our knees the one to the other… do you think we are the only fools of the universe?”

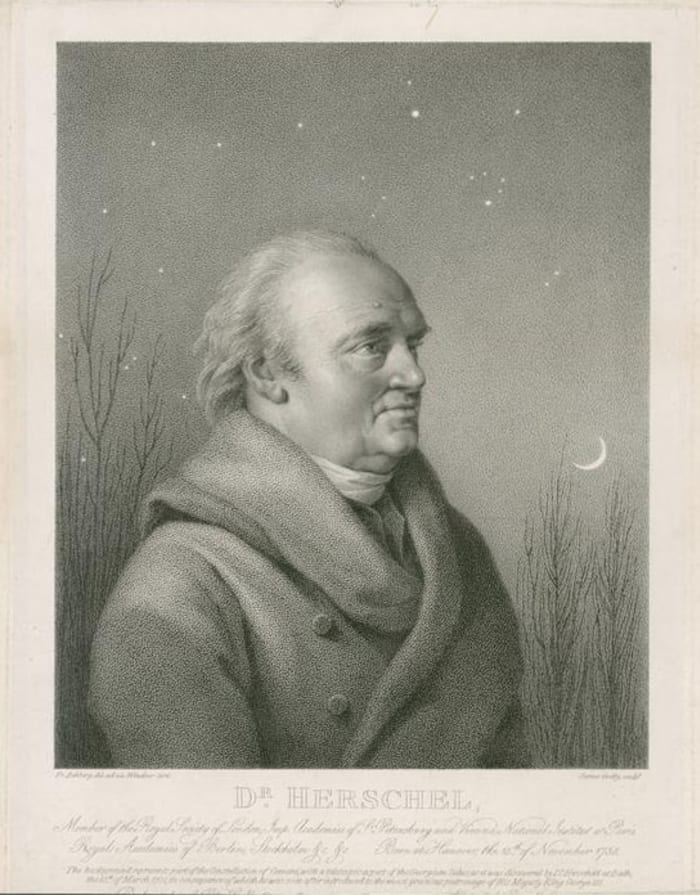

While it could be misconstrued as a flight of fancy out of context, the speaker is posing an earnest question to the reader. Plurality Of Worlds was written as a philosophical text, and is considered by some to be the first book of the Age of Enlightenment, a period of human inquiry that would change the course of Western history. Newton, Rousseau, and Locke are products of this time period, as are the American and French Revolutions. This particular inquiry is discussed commonly, and by some notable natural philosophers (scientists), including the famous astronomer William Herschel, discoverer of the planet Uranus (though, thankfully, he didn’t name it):

“...we find, even upon our globe, that there is the most striking difference in the situation of the creatures that live upon it… man walks upon the ground, the birds fly in the air, and fishes swim in water… if those that are to inhabit [the Moon’s] regions are fitted to their conditions as well as we on this globe to ours… I believe the analogies that have been mentioned fully sufficient to establish the high probability of the moon’s being inhabited like earth.”

Herschel is so certain that there are inhabitants beyond Earth, he makes the case for every surface in the Universe to host beings. He states that, “...the sun is richly stored with inhabitants,” and in addition, “the stars are suns, and suns are inhabitable…” concluding, “we may have an idea of numberless globes that serve for the inhabitation of living creatures.” A contemporary of Dr. Herschel, who writes anonymously, takes it a step further in a treatise concerning Jupiter and Saturn. “...we have every reason to believe the planets are inhabited, both from philosophy and religion… the psalmist says, ‘WHO HUNG THE WORLDS UPON NOTHING,’” and James Ferguson, author of the famed Ferguson’s Astronomy (which can be found in Richard Charlton’s library at The Coffeehouse on Duke of Gloucester Street), questions, “...to what purpose could the sun shine upon lifeless lumps of matter, if there were no rational creatures upon them to enjoy the benefit of his light and heat… I could never believe that the Almighty does anything in vain.” John Adams of London goes so far as to speak condescendingly of anyone who might disagree with this notion in 1793’s The Elements Of Knowledge...:

“Whoever imagines that so many glorious suns were created only to give a faint glimmering light to the inhabitants of this globe, must have a very superficial knowledge of astronomy, and a mean opinion of the divine Wisdom… Dare we, who, in comparison with the universe, are mere insects, creeping over that little spot called earth, prescribe bounds to all Nature!... Even those minds, which are the least tinctured with philosophy, begin to familiarize with this idea of millions of worlds…”

Millions of worlds filled with all kinds of fantastical creatures. In the 21-century, our perception of extraterrestrial life is usually some variant of “Little Green Men,” thanks to the Hopkinsville, Kentucky Alien Encounter of 1955. Our Enlightenment stargazers, however, had their own interpretation of these creatures. In general, though, the agreement is that inhabitants of different worlds could not appear in the image of mankind. The Sun and Mercury are too hot, while Jupiter and Saturn, too cold. Of course, all of this is speculation on the part of the various authors, but some common themes seem to arise. In 1790, Dr. Ferguson writes in An Easy Introduction To Astronomy...

“...if the pupils of their eyes who live on the planet Mercury are seven times as small as ours are, the light will appear no stronger to them than it doth to us here. And if the pupils of their eyes who live in Saturn are ninety times as large as ours (which they will be, if they are nine times and a half as large in diameter as ours…) the light there will be of the same strength as it is to our eyes here.”

Other descriptions, however, are... less scientific in nature:

“Father Kircher,” writes our friend Dr. Adams, “transported himself in idea to all the planets… Saturn, he says, is people with melancholy old men, who have pale visages and stern looks, and who, cloathed [sic] in dismel distress, march along with a slow pace, bearing in their hands flaming torches. In Venus, he observed young people, of the finest figure and most exquisite beauty, some of whom danced to the sound of harps and cymbals, whilst others feattered, in great profusion, odours and perfumes.”

While descriptions of the inhabitants of various planets in our solar system differ with almost every author, one point seems to be, dare I say, universally understood: We really have no idea what these creatures might look like. Plurality Of Worlds remarks upon this in a beautifully self-reflective passage:

“...put the case that we ourselves inhabited the moon, and were not men, but rational creatures, could we imagine, do you think, such fantastical people upon the earth as mankind is? Is it possible we should have an idea of so strange a composition; a creature of such foolish passions, and such wise reflections; allotted so small a span of life, and yet pursuing views of such extent? so learned in trifles, and so stupidly ignorant in matters of greatest importance? so much concerned for liberty, and yet such great inclination to servitude? so desirous of happiness, and yet so very incapable of attaining it?”

The old phrase goes, “The sky’s the limit.” For centuries, though, humanity has gazed beyond the bounds of Earth in wonder. Just as today, the universe of the 18th century was expanding, and as humanity’s knowledge increased, more questions arose. How big is all this? What does it all mean? Are we alone? Thanks to modern instruments, we now know the cosmos expands well beyond even our own Milky Way, whereby the thousands of stars visible to us in the night sky give way to an unfathomable expanse of other galaxies, each with billions or trillions of its own suns, making it seem almost inevitable that somehow, somewhere life must exist. As philosophers and common people alike considered the question of “inhabitants” elsewhere 300 years ago, this same, overwhelming feeling is expressed by one Dr. Young, as noted in 1782 by S. Harrington:

“One sun by day — by night ten thousand.”

*Some of the Principal Inhabitants of ye Moon, William Hogarth, London, 1724, engraving on laid paper, Museum Purchase, 1972-409,13

Robert Weathers has been working as a first-person interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg since January 2008. Over the past several years, he has studied the astronomical revolution of the mid- to late-18th-century, and will premiere as a Nation Builder in the fall, portraying George Wythe. When he is not in breeches, he can often be found wearing shorts no matter the weather, and riding roller coasters with his wife Kaitlyn.