What these iconic prints tell us about John Custis IV when we use art to inform archaeology

John Custis IV (1678-1749)(1) not only had one of Williamsburg’s most important gardens, but he also had one of the largest art collections in the city. His interests came together in 1730 when a Kensington nurseryman named Robert Furber (c. 1674 – 1756) published twelve engravings of flowers that served as both decorative prints and seed catalogue. Each print features flowering plants in bloom for each month of the year, tastefully arranged in decorative urns. They were at the height of fashion and a must-have for anybody-who-was-anybody interested in gardening at the time John Custis ordered them from London.

Furber’s Twelve Months of Flowers might be familiar to long-time fans of Colonial Williamsburg through reproductions sold in our gift shops. Just as they were both decorative, yet functional when they were originally published, contemporary scholars and historians refer to these prints to understand the types of flowers, shrubs, and trees that excited the botanical community in eighteenth-century England and overseas. As Colonial Williamsburg’s team of archaeologists continue to make discoveries at the site of John Custis’ Home And Famous Garden, let’s take a look at the story behind these prints and what Custis’ purchase tells us about his role as arbiter of taste and a master gardener.

In 1734, Custis wrote to his London merchant John Cary to express his pleasure at receiving “the flower pieces you sent me.” By “pieces”, in this instance, Custis was referring to engravings, specifically the Twelve Months of Flowers published by Robert Furber. The twelve sheets of paper survived the perilous overseas journey that often destroyed cargo and arrived safely in his home in Williamsburg. Custis, who could find fault with just about anything, was still not satisfied. Something was missing. His letter continued,(2)

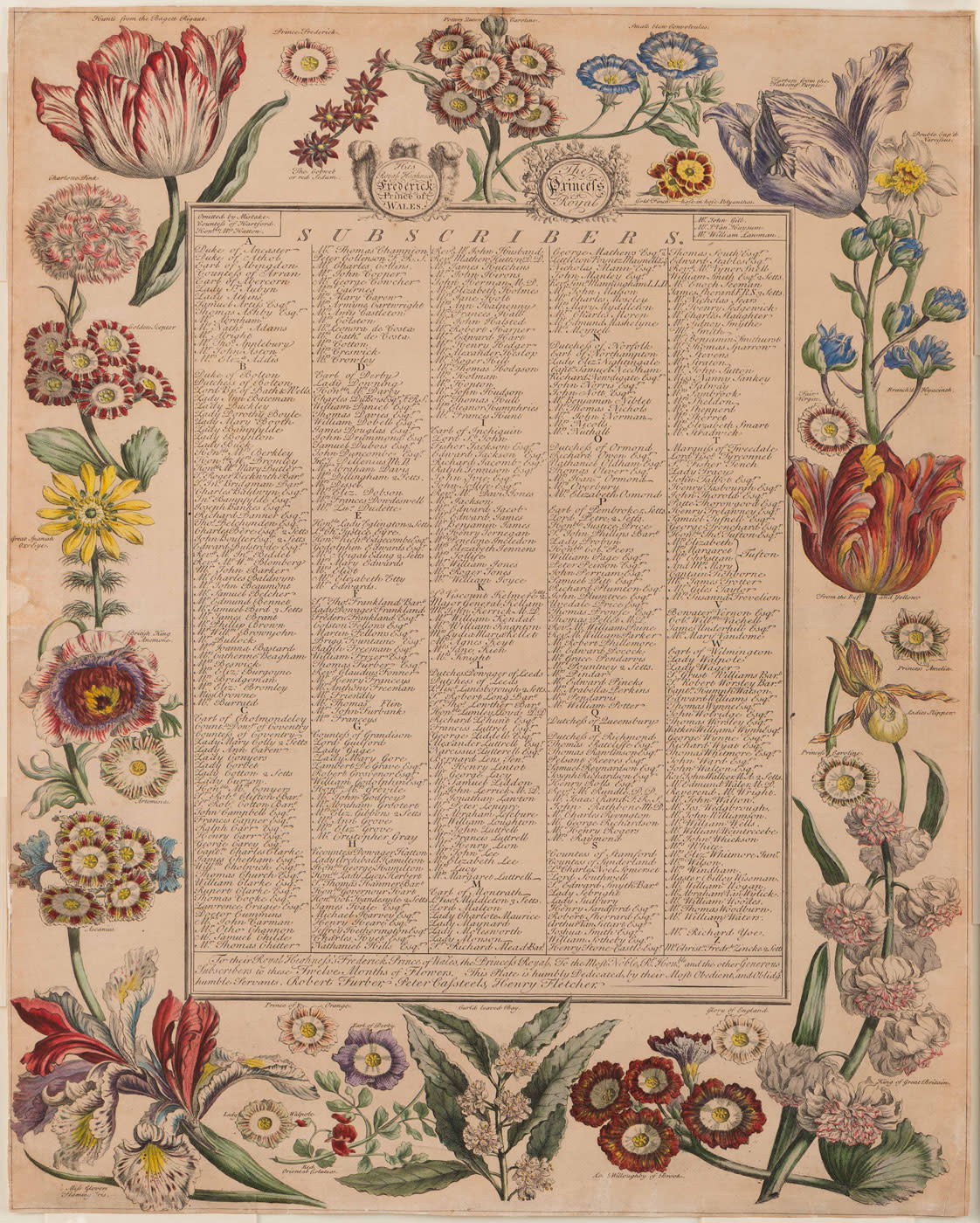

“…the man [Furber] has not done me justice – in not sending the thirteenth print with[sic] the subscribers names w:ch I find he has sent to other Gentleman, Coll Lee for one. He continued to Cary, “I hope you will order him to send it me still; I believe I have got him severall Customers…”

The “thirteenth print”, Custis referred to was the subscription sheet, which listed the names of individuals that had funded the initial publication in advance. Though Custis was not an original subscriber, he would have been keenly interested in learning the names of other enthusiasts of botany from across the pond. The subscription sheet also included some additional flowers not depicted on the other prints including a tulip similar to the one that Custis was famously depicted with in his portrait by Charles Bridges.

Custis saw himself as the one who had secured “severall” Virginia customers for Furber, having informed fellow members of the Virginia gentry about the fashionable prints. At least one such lucky individual received the subscription sheet, according to the letter — Custis’ friend, Thomas Lee of Stratford Hall in Westmorland County, Virginia, whose probate inventory at the time of his death listed: “19 Flower pieces & old picturs” in the “Green Room.”(3) Custis was offended that some of his friends had received the thirteenth sheet, while he had not.

Custis’ complaint tells us that he saw himself as an arbiter of taste and reveals his active involvement with the world of horticulture, even if most of that conversation was going on the other side of the ocean. In fact, Furber’s Twelve Months of Flowers were more than pretty pictures to hang on the walls; they were an ingenious marketing tool conjured up by England’s most fashionable nurseryman. These prints were the first illustrated seed catalogue published in England.

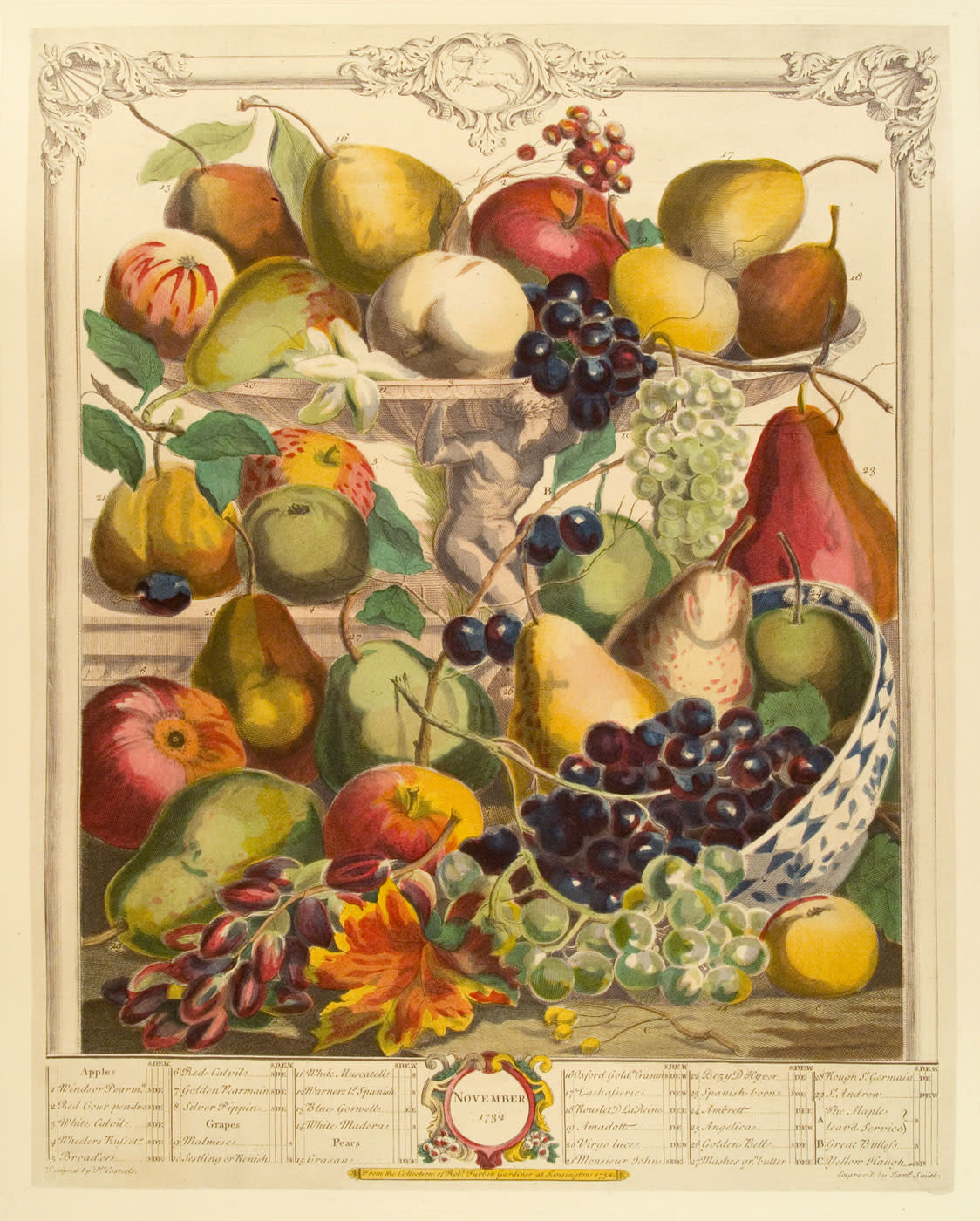

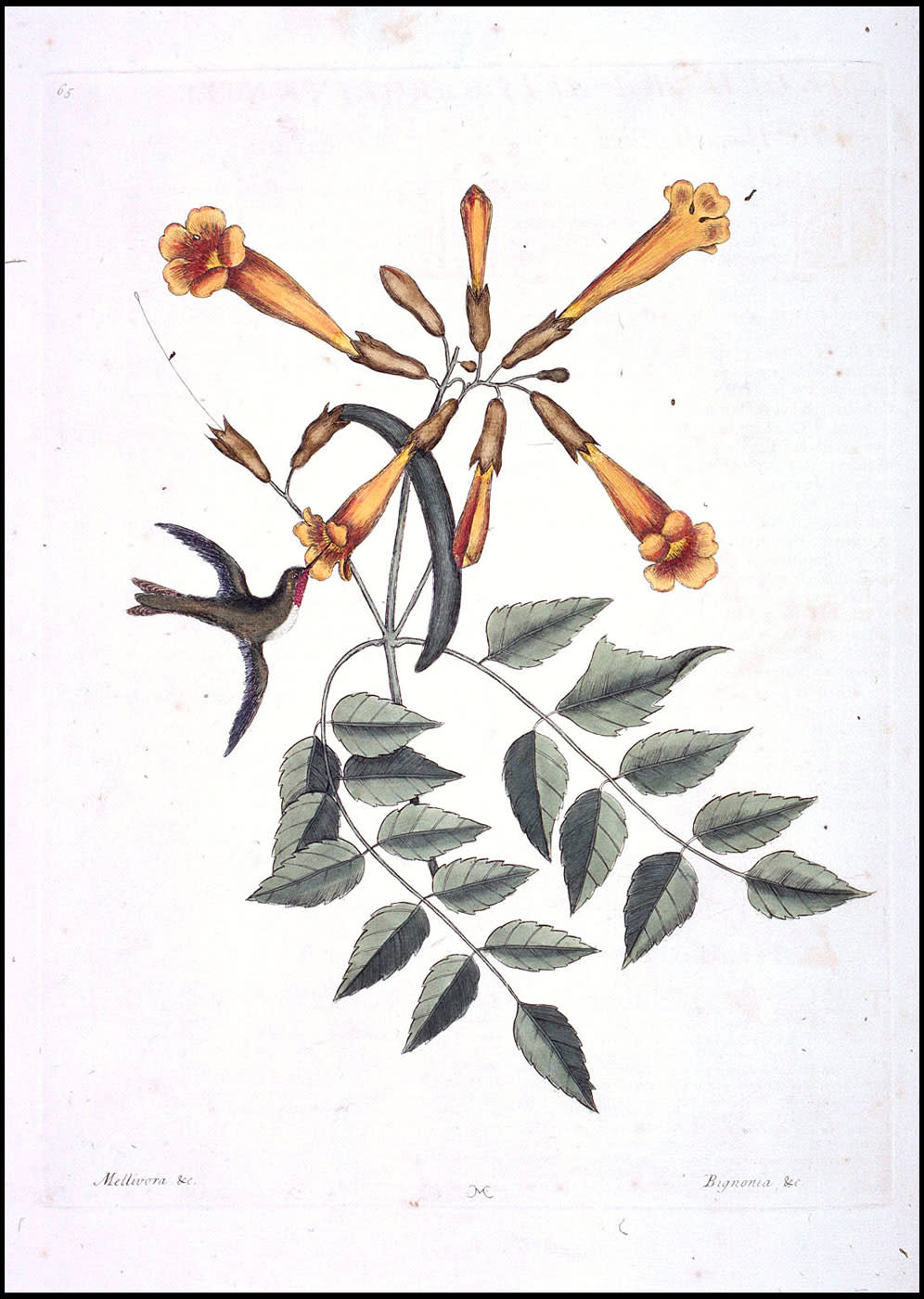

In 1730, a London nurseryman named Robert Furber advertised that he intended to publish a set of twelve prints, one for each month of the year depicting the flowers that were in bloom for that particular month. The prints were based on paintings by the Flemish artist Pieter Casteels III and engraved by Henry Fletcher. Though beautiful, these prints were not purely decorative, but a cleverly devised marketing scheme to promote Furber’s nursery in Kensington. Furber promised that there would be upwards of 30 different kinds of flowers per print, with each flower labeled with a number and identified at the bottom of the print. And they were all available for purchase from his nursery. Ultimately, the twelve prints represented nearly 400 different flowering species.

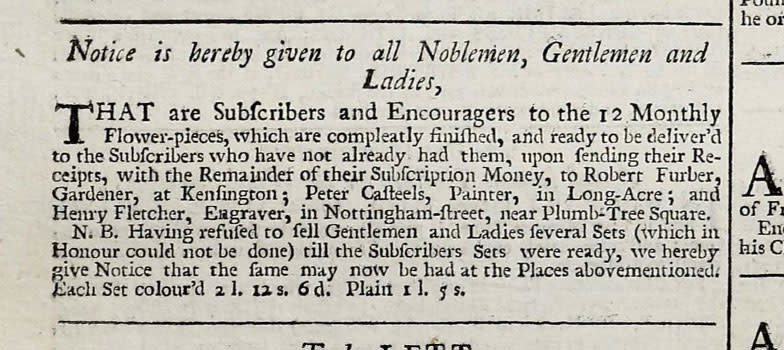

The prospectus issued to gather financial support for the project listed a hand-colored set, including a sheet listing the subscriber’s names (for a limited time only) cost 2 guineas for subscribers and 2 and a half for non-subscribers. If you could not spring for a hand-colored set, in which every flower was painted individually to reflect their characteristics, you could purchase an uncolored set for 25 shillings. In April 1731, Furber announced in the London papers that the twelfth print was nearly complete and the whole collection would soon be delivered “very speedily.” As an added bonus he noted:(4)

“And also that in Token of Gratitude, we intend to add a 13th Plate with the Subscribers Names in a Border of such Flowers as are not in the other Plates; to be deliver’d only to those who shall please to subscribe before the 25th of this instant April.”

This was the subscription list that Custis coveted so much. The subscription listreveals the fashionable status of Furber’s clientele, many of whom were upper class members of English society. Among the names are members of the nobility including the Prince of Wales and the Princess Royal and ten Dukes and Duchesses.(5) The list is also notable for the high percentage of female subscribers, 126 out of the total 457. In his marketing efforts, Furber tried to enhance the appeal of the series, suggesting that they were not only useful for gardeners and botanical enthusiasts, but they could also serve as design sources for “Painters, Carvers, Japaners &c Also for the Ladies as Patterns for working and Painting in Water-Colours; or Furniture for the Closet." (6) Riding high on the success of the botanical prints, he announced the publication of Twelve Months of Fruit, which would garner 561 subscribers, 171 being members of the print trade, indicating just how popular the genre he created had become.(7)

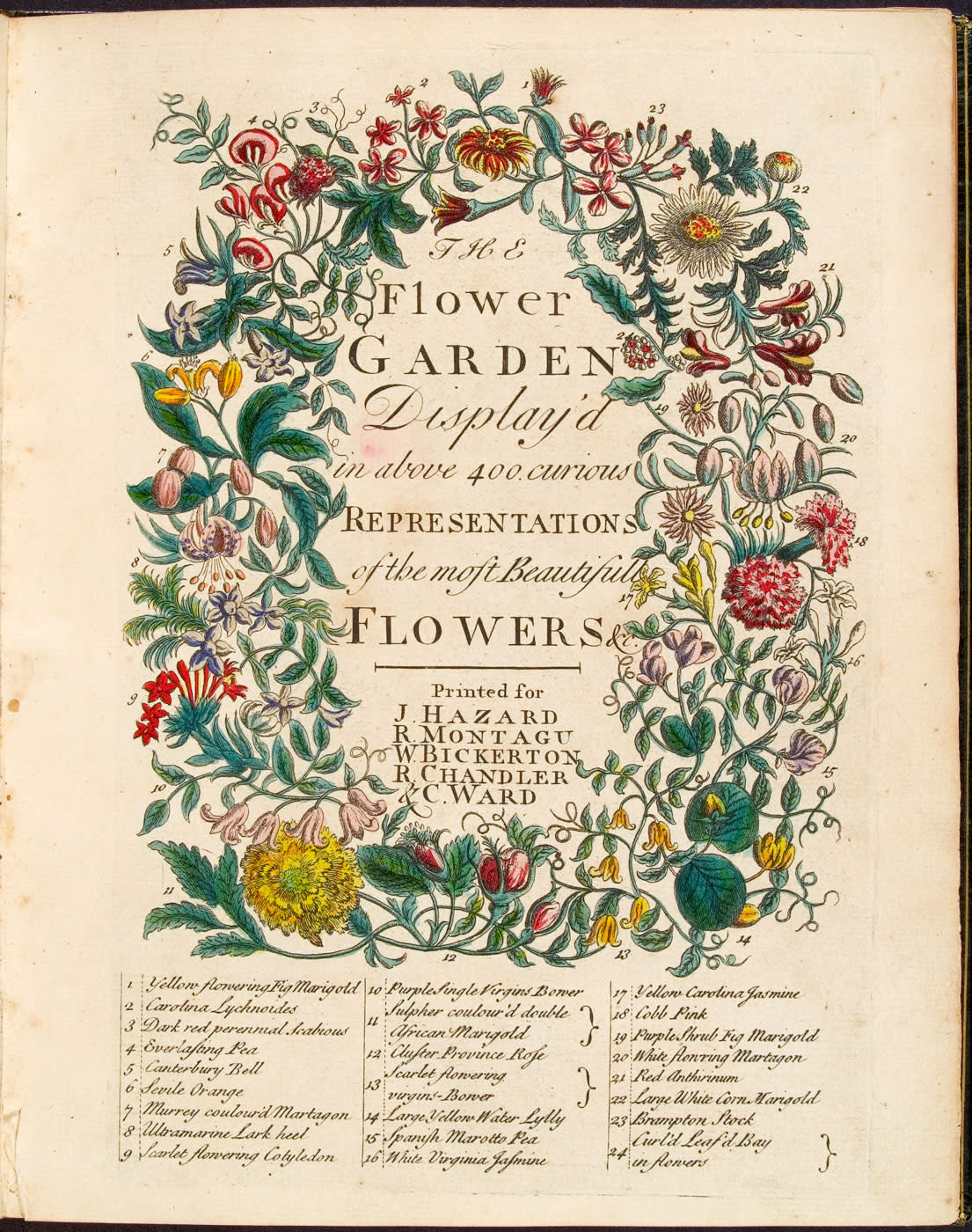

The flower prints were an immediate success and, accordingly, knock-offs quickly followed suit. For example, print seller John Bowles announced a set of Twelve Months of Flowers the same year Furber’s prints were released. They were almost identical, except for their size (14 ¼” x 10 ½”) and the fact that the image was reversed.(8) In 1732, a small anonymous book entitled The Flower-garden Display’d was published by a group of booksellers in London containing “the Designs of Mr Furber and others.” (9) The quarto-sized (10 1/2” x 8 1/3”), more affordable book contained reduced copies of Furber and Casteels designs with text later attributed to Richard Bradley, professor of botany at Cambridge between 1724-1732.(10) Furber was swift to condemn the book as a copy, stating in March 1732 that, “…those Prints are only Copies, and that we are not any ways concern’d in ‘em, but the Originals, which are only sold by us…”(11) He also published another notice in the London papers to “prevent the Publick being imposed on by spurious Copies sold about town” with the exact dimensions of his print’s plate marks (for size), authorized retailers, and identifying marks.(12) Despite these efforts, the imitations continued. The library of Custis’ brother-in-law, William Byrd II of Westover, lists a copy of The Flower-garden Display’d.(13)

At the time Furber published the prints, there was a craze in Britain for exotic or rare botanical specimens recently introduced to England from Asia, Africa, South and North America.(14) Furber’s prints contained a number of American specimens, including at least two-dozen that were introduced to England from America by the naturalist Mark Catesby. In 1712, Catesby traveled with his sister to Williamsburg, where her husband was a well-connected doctor who introduced the young naturalist to a group of wealthy men who were interested in natural history. This group included John Custis. Catesby, who authored one of the earliest and most important natural histories of the American south, Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and The Bahama Islands, stayed in touch with Custis after leaving America.

Catesby and Custis were members of a transatlantic network of like-minded “curious” gentleman botanists, naturalists, and artists who exchanged their knowledge, plants, seeds, and wisdom. In 1734, the same year he wrote to Cary about Furber’s prints, Custis began what would be lengthy correspondence with well-known horticulturalist Peter Collinson, a subscriber of Furber’s prints. Their letters are one of the best sources on gardening in eighteenth-century America.(15) Though the two men never met in person, Collinson and Custis exchanged plant specimens for years, adding to each other's collections and sharing their rich experiential botanical knowledge. Closer to home, he exchanged advice and specimens with naturalist John Bartram of Philadelphia (who visited Custis’s garden in 1738), John Clayton of Gloucester Virginia, and his brother-in-law William Byrd II. It was within this vast network, in which Custis found himself a contributor and avid participant.

Custis’s garden was surpassed by few in the eighteenth century.(16) The garden comprised nearly four acres, with walkways, statuary, topiary, orchards and vegetable plots. Though Custis was heavily involved in the management, design, and supervision of the garden, it was maintained by an enslaved workforce. The majority of their stories remain untold, but through archaeological excavation of the site, we hope to learn more about the lives, contributions, and influences of these enslaved gardeners on the landscape.

During previous archaeological excavations, fragments of earthenware urns have also been found on the Custis site in the style of the urns depicted in Furber’s prints. In 1736, Custis ordered “6 flower pots painted green to stand in a chimney to put flowers in the summer time wth[sic] 2 handles to each pot…”(17) The fragments of urns found archeologically are red rather than green, perhaps another indication that Custis’ English merchants didn’t always provide him with exactly what he desired.

Custis’s ownership of Furber’s flower prints is but one additional piece of evidence that he kept up-to-date on English advancements in natural history and gardening from Williamsburg. In addition to his collection of plants, Custis was an avid collector of prints, paintings, and sculpture. At the time of his death, his inventory listed over 140 art objects, an incredible collection for this period in America. Hanging in the first floor Hall or parlor were “a Sett of Fruit pieces” and “a sett of Flower pieces” valued at 5 pounds per set.(18) The inventory indicates that the Hall was adjacent to a space known as “the Closet next to the Garden.”(19) Presumably, from this space, Custis could study his coveted prints of flowers and fruit while looking out upon his beloved garden at some of the specimens they contained including tuberose (October no.1), hollyhocks (August no. 17, October no. 30, November no. 36), pilewort (February no. 35), jasmine (see June, July, August), crocus (see February), and more.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Katie McKinney

Assistant Curator of Maps and Prints, Katie McKinney has worked for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for three years. She holds a master’s degree from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware and a BA in art history and history from James Madison University. A native of Williamsburg, she started her "career" at the age of nine in Colonial Williamsburg's Junior Interpreter program and has never looked back.

McKinney wishes to thank Director of Archaeology Jack Gary for the invitation to write on this topic. She would also like to thank Margaret Pritchard, Adam Erby, Jason Copes, Pam Young, Angelika Kuettner, Laura Pass Barry, Marianne Martin, Doug Mayo, and Tracey Gulden.

Resources

1.For more information on the life of John Custis see Aaron Lovejoy and A production of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Department of Archaeology, The Custis Family Migration; Josephine Little Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg, 1678-1749,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 90, No. 2 (April 1982), pp. 177-197; and Custis and Zuppan, The letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717-1742 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

2.Custis and Zuppan, The Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717-1742 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), pp. 140-141.

3.Thomas Lee, Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia, Westmoreland County Records 4 1756-1767 p. 76-79, Taken: August 17, 1758, Recorded August 29, 1758. An Inventory and appraisement of the Estate of the Late President the Honorable Colo. Thomas Lee of Stratford in Virginia the Estate in Westmoreland County August 17th, 1758, p, 2.

4.“Advertisement,” Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal, London England, Saturday April 3, 1731, Issue CXXX.

5.For a detailed breakdown of the subscribers see Timothy Clayton, The English Print, 1688-1802 (New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 1997) 132-134.

6."Multiple Advertisements," Universal Spectator, and Weekly Journal, 28 Oct. 1732. 17th and 18th Century Nichols Newspapers Collection, HTTP://TINYURL.GALEGROUP.COM/TINYURL/99GE60. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

7.Clayton, The English Print, 134.

8.For other copyists see Clayton, English Prints, 130-131.

9.This language was used both in newspaper advertisements to refer to the book as well as on the frontispiece of the book.

10.Catalogue of Botanical Books in the Collection of Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt, Printed Books 1701-1800, Allan Stevenson (compiler), vol.1, pt. 2 (Pittsburgh: The Hunt Botanical Library, 1961), xxii; Ibid, vol. 2, pt. 2, Hunt 487, Hunt 493.

11."Multiple Advertisements." Fog's Weekly Journal, 18 Mar. 1732. 17th and 18th Century Nichols Newspapers Collection, HTTP://TINYURL.GALEGROUP.COM.PROXY1.LIBRARY.JHU.EDU/TINYURL/BUDZW1. Accessed 7 Aug. 2019.

12. “Advertisement,” Fog's Weekly Journal, London, England, Saturday, March 25, 1732; issue 177. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers.

13.Kevin J. Hayes, The Library of William Byrd of Westover (Madison, WI: Madison House Publishers Inc./ in cooperation with The Library Company of Philadelphia), Case A, Second Shelf, Folio, 1846, p. 458.

14.For more on the English’s interest in foreign plants, particularly from America see Mark Laird, “Retailing Favours and Taking up Cudgels: Coffee House to Commerce in the Art of Mark Catesby and Jacobus van Huysum,” in A Natural History of English Gardening, 1650-1800 (New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press), pp. 126-165.

15.To read their correspondence see Earl Gregg Swem, Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia, 1734-1746 (Barre, MA: Barre Gazette, 1957).

16.To learn more about Custis’ garden see: Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991).

17.Zuppan, Letterbook, p. 171.

18. “III-A-1. Combined County Inventory of Slaves and Personal Property in the Estate, 1757–58,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, HTTPS://FOUNDERS.ARCHIVES.GOV/DOCUMENTS/WASHINGTON/02-06-02-0164-0006. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 6, 4 September 1758 – 26 December 1760, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 220–232.]

19. Ibid.