The beginning of Modern Aviation

Many a visitor to Williamsburg, while driving on Richmond Road past the College of William and Mary have no doubt seen the Virginia Historical Marker W-40, which reads,

“On May 7, 1801, J.S. Watson, a student at William and Mary, wrote a letter detailing attempts of flying hot air balloons on the Court House Green. The third balloon, decorated with sixteen stars, one for each of the existing states, and fueled with spirits of wine, was successful. Watson wrote, ‘I never saw so great and so universal delight as it gave to the spectators.’ This is the earliest recorded evidence of aeronautics in the commonwealth.”

I wonder how many have given it anymore thought than that? Or how these early adventurers opened the door to the modern world.

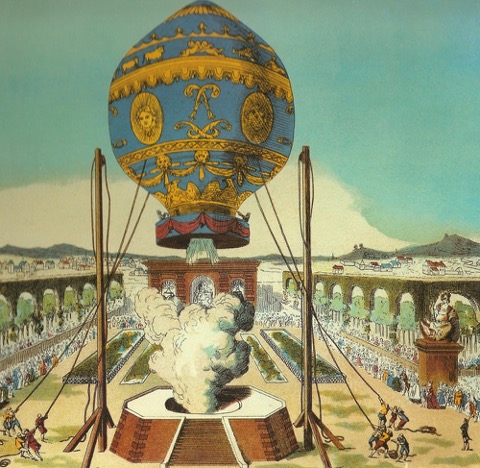

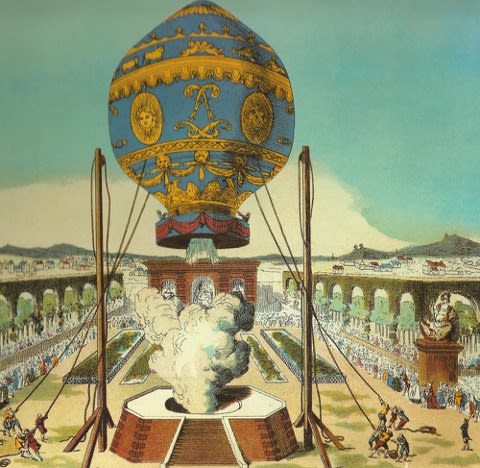

As any fans of our Jug Broke Theatre Company will know, the Montgolfier brothers in France had been experimenting with balloons in 1782 and in the following year, they flew the first living creatures, a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. Just as our early space flights flew dogs and chimpanzees, these animals flew first to determine if it was safe to ascend at all. The following month, the first manned tethered balloon flight was made and then a month later, the first un-tethered flight. Among the audience at those first ascensions in France were three representatives of our young country: Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay. Stories began to appear in the papers and a balloon mania spread throughout the world. Soon balloons motifs appeared in jewelry, clothing and furniture, and several other aeronauts began to take to the skies including the first gas (hydrogen) balloon in December of 1783. Benjamin Franklin wrote,

“Among all our circle of friends, at all our meals, in the Antechambers of our lovely women, as in the academic schools, all one hears is talks of experiments, atmospheric air, inflammable gas, flying cars, journeys in the sky.”

George Washington was not immune to this excitement. In April he wrote to his former Chief Engineer Louis Le Bèque du Portail,

“I have only newspaper accts. of Air Balloons, to which I do not know what credence to give. The tales related of them are marvelous and lead us to expect that our friends at Paris, in a little time, will come flying thro’ the air, instead of ploughing the ocean to get to America.”

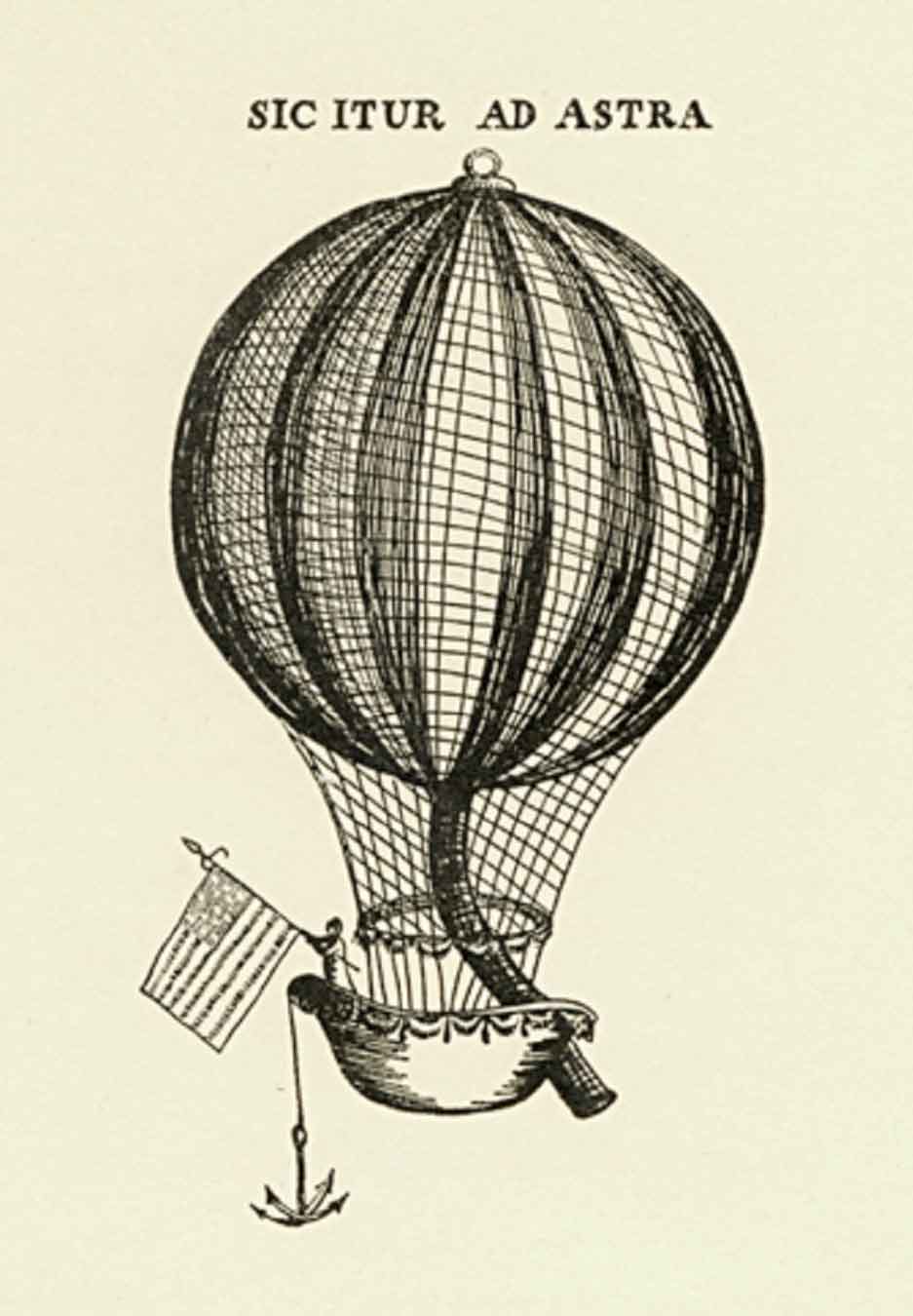

Eventually he would have his chance to verify these claims himself. On January 19th, Jean-Pierre-François Blanchard, now one of the most successful and famed balloon pilots made an assent from the yard of the Walnut Street Prison. President Washington was there and provided Blanchard with the following letter,

“George Washington, President of the United States of America, to all to whom these presents shall come. The bearer hereof, Mr. Blanchard a citizen of France, proposing to ascend in a balloon from the city of Philadelphia, at 10 o'clock, A. M. this day, to pass in such direction and to descend in such place as circumstances may render most convenient— These are therefore to recommend to all citizens of the United States, and others, that in his passage, descent, return or journeying elsewhere, they oppose no hindrance or molestation to the said Mr. Blanchard; And, that on the contrary, they receive and aid him with that humanity and good will which may render honor to their country, and justice to an individual so distinguished by his efforts to establish and advance an art, in order to make it useful to mankind in general.”

I often see this referred to as the first airmail, I would suggest instead, that it is the first aviator’s license.

But what of William and Mary?

A balloon club formed, organized by the Reverend James Madison, cousin to the future President. By 1786, they were building their own hot air balloons. Joseph Shelton Watson was a student at William and Mary between 1798 and 1801. In April of 1801 he would write to his brother “I have been engaged in for several evenings in the construction of an Air-balloon. I’ll let you know in my next whether it succeeds.” The following month, powered by the Spirits of Wine (Ethanol Alcohol), it did.

It would be easy to simply write these adventures off as a simple folly. Certainly, these balloons were beautiful, and the sense of adventure captured the people’s attention, but more importantly, they marked a change. A radical alteration in our understanding of physics and chemistry. They also showed the public, quite literally, that a deeper understanding of nature could create miracles, and that even gravity need not restrain the human spirit. In time, these experiments would lead to Washington’s vision of “Flying thro’ the air rather than ploughing the ocean,” and with that, all of our modern aviation.

Ron Carnegie has worked for Colonial Williamsburg for almost 25 years. He has been involved in many different aspects of Colonial Williamsburg’s various activities, most recently portraying George Washington.