There are 1,320 words in the Declaration of Independence; 1,337 if you include its title. If you add all of the signers’ names, then the Declaration of Independence contains 1,458 words.1 If Americans cannot agree on something as simple as the number of words in our nation’s founding document, how can we possibly expect all Americans to agree on what the words in the declaration mean and how the Founding Generation meant them?

As this year’s July Fourth episode of the Ben Franklin's World podcast reminds us, our plurality of perspectives is not a bad thing. In fact, the freedom to share one’s voice without fear of consequence comprises a central part of living in a free society. The ability to question, critique, celebrate, and support differing opinions was foundational to the creation of the United States and it remains a core component of American culture today.

When researching eighteenth-century life, historians are always thinking about perspectives and how they can collect more of them. It is only by studying moments in the past from a variety of viewpoints and with a range of historical sources that we gain the fullest, most complete picture of how a past event shaped the society that British colonists lived in.

If we want to understand the world the people of the new United States lived in, we must seek out multiple perspectives on moments like the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The sources the Founders and other leading voices of the early United States left behind tell us what they thought and felt about the declaration. We know that the fifty-six white men who put their names to the parchment benefited from the United States’ monumental break from Great Britain.2 And as the official leaders of this new country, they offered (mostly) white, property-owning men the opportunity to have a voice, a vote, and to contribute to something revolutionary.

But what about the rest of those living in the new United States? If we add more perspectives to those of the Founders, our understanding of the implications of the Declaration of Independence expands and grows more complete.

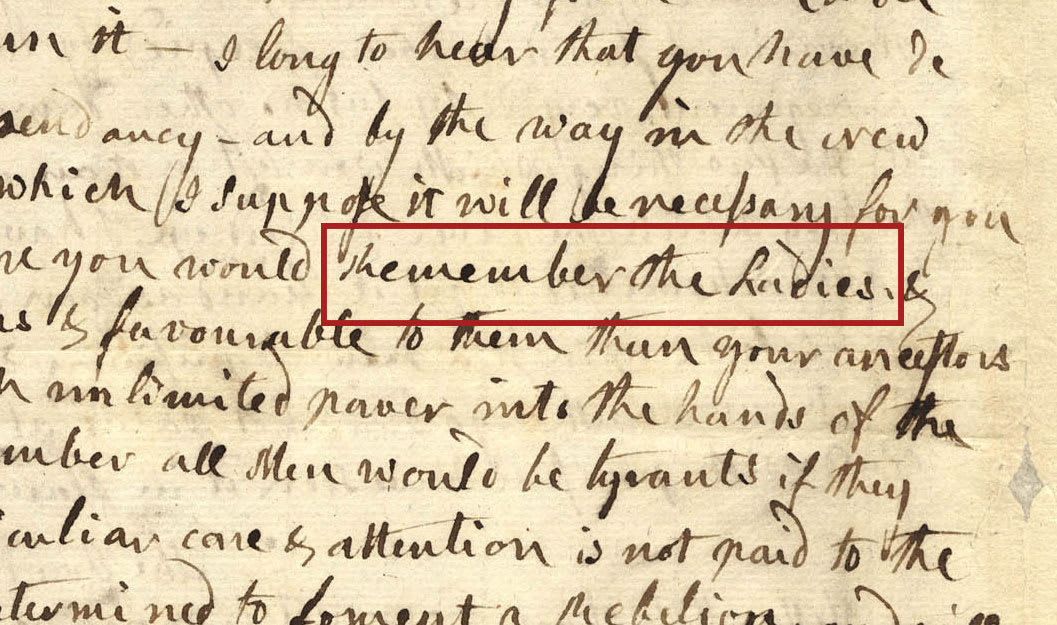

Women also left behind sources that reveal their perspectives on the Declaration of Independence. In March 1776, Abigail Adams’s letter to her husband, John, reminded him to “Remember the Ladies…,” knowing that members of the Second Continental Congress were beginning to think of independence.3 Revolutionary women, like Abigail, were undoubtedly disappointed when their rights were left out.

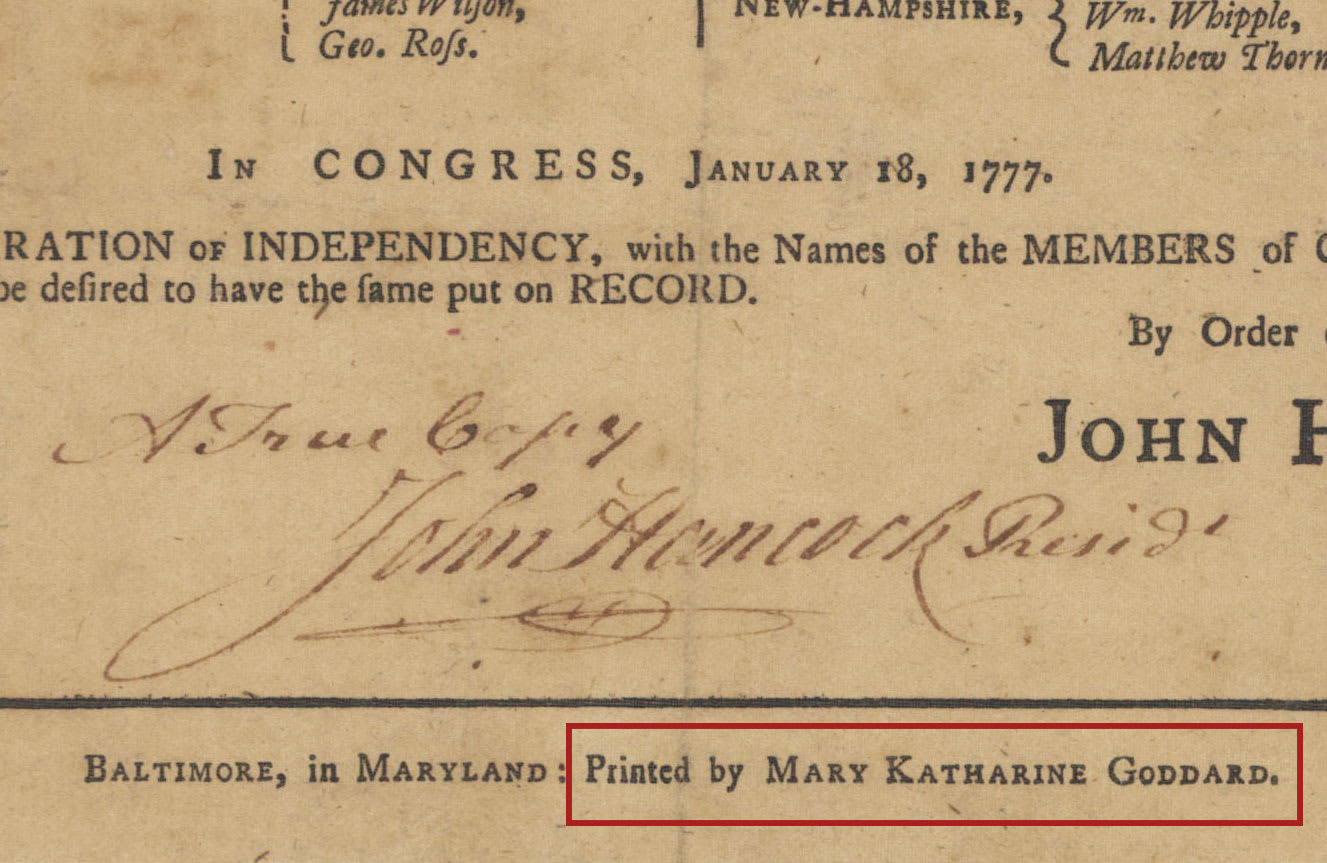

In December 1776, Baltimore printer Mary Katharine Goddard was commissioned by the new United States government to produce a second printing of the declaration, the first to include all of the signers’ names. Goddard’s name also appeared on the January 1777 broadside, which has been interpreted as her signing alongside the Founders. Consequently, Goddard is credited as the only woman whose name appears on the Declaration of Independence.4

Printings of the Declaration of Independence were critical to the spread of its ideas, but so too were the events in which the declaration was read aloud. Nine-year-old James Forten heard a reading of the declaration at the Philadelphia State House on July 8, 1776.5 The Declaration of Independence’s words fundamentally impacted Forten, a free Black child who worked among the enslaved on a daily basis. Hearing the words of the declaration inspired him to support the revolutionary cause as a privateer at the age of fourteen. Once the war ended, Forten dedicated the rest of his life to uplifting his fellow Black Americans. His goal was that all Americans could enjoy the rights bestowed by the Declaration of Independence, regardless of color.

And yet, the Declaration of Independence did not inspire everyone. William Howe, the commander in chief of the British forces in North America and his older brother, Vice Admiral Richard Howe, issued the first official British response to the declaration in September 1776. The Howes described the Declaration of Independence as an "extravagant and inadmissible claim."6 A month later, in his opening speech to Parliament, King George III refused to recognize the declaration and labeled American “leaders” as “daring and desperate.”7

Those who were enslaved would have likely found the words of the Declaration of Independence ironic, if they ever heard them. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s famous 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” questioned why the freedoms promised in the Declaration of Independence had not yet been extended to Black Americans seventy-six years after its signing.8

For Native Americans, who the Declaration described as “merciless Indian Savages,” Americans declaring independence likely proved concerning.9 The Proclamation Line of 1763 and the British soldiers who enforced it deterred colonists from expanding further west into American Indian land.10 The Cherokee and the Shawnee, for example, believed that the Declaration of Independence would lead to the further loss of land and destruction of their communities and cultures.11

Finally, it is important to remember that even among the men who stood to immediately benefit from this country’s creation some did not see the Declaration of Independence as a step in the right direction. The prominent and politically connected Allen family of Philadelphia initially supported the revolutionary cause. William Allen, the youngest son, even commanded a battalion of Pennsylvania Continentals. However, once Allen heard news of the Declaration of Independence, he immediately resigned his position and aligned himself fully with the British.12 For Allen, American rights were a worthy cause, but a full break from Great Britain was too much to consider.

By placing these stories in conversation with one another today, we can expand our understanding of the Declaration of Independence. The declaration was a document that inspired hope, promised freedom, launched a country, but it also caused frustrations and evoked fear.

Histories need to include as many voices as possible because their inclusion helps us better understand and make meaning of our shared past. It is only when we look at events from multiple perspectives that we can gain a fuller, more complete picture of what it was like to live and work in early America and how so many different people contributed to the formation and evolution of the United States.

Endnotes

- “What Is the Word Count of the Declaration of Independence,” Declaration Resources Project, Harvard University, https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/faq/what-word-count-declaration-independence.

- For a complete list of signers of the Declaration of Independence, see “Who Signed the Declaration of Independence,” Declaration Resources Project, Harvard University, https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/faq/who-signed-declaration-independence.

- Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March–5 April, 1776, Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17760331aa.

- For more on Mary Katharine Goddard, see Erick Trickey, “Mary Katharine Goddard, the Woman who Signed the Declaration of Independence,” Smithsonian, November 14, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/mary-katharine-goddard-woman-who-signed-declaration-independence-180970816/; “Mary Katharine Goddard Takes a Stance,” National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/independence-goddard.htm.

- “Big Idea 1: Young James Forten’s World”, Museum of the American Revolution, https://www.amrevmuseum.org/big-idea-1-young-james-forten-s-world.

- Richard Howe and William Howe, “By Richard Viscount Howe of the kingdom of Ireland, and William Howe, Esq; general of his majesty’s forces in America: the King’s Commissioners for Restoring Peace to His Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations in North America, &c., &c., &c. Proclamation,” 1776, Rider Broadsides, Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library, https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:380209. For more, see “August Highlight: A Tale of Two Declaration,” Declaration Resources Project, Harvard University, https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/august-howe.

- See also “September Highlight: Extravagant and Inadmissible Claim of Independency,” Declaration Resources Project, Harvard University, https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/september-kings-speech.

- “A Nation’s Story: ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,’” National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

- Full line: “He [King George III] has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

- For a brief explanation of the Proclamation Line of 1763, see “Proclamation Line of 1763,” Geogre Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/proclamation-line-of-1763/.

- On the Cherokee, see Nadia Dean, “A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776,” American Indian, Winter 2013, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/demand-blood-cherokee-war-1776; William L. Anderson, and Ruth Y. Wetmore, “Cherokee,” in NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/cherokee/revolutionarywar; Jordan Baker, “The Cherokee-American War from Cherokee Perspective,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 29, 2021, https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/07/the-cherokee-american-war-from-the-cherokee-perspective/.

- For more on William Allen and his family’s shift from Revolutionaries to Loyalists, see Robert N. Fanelli, “William Allen and His Family: Tories or Patriots?,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 2, 2020, https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/12/william-allen-and-his-family-tories-or-patriots/; Todd W. Braisted, “British Thoughts on American Independence,” American Battlefield Trudst,https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/british-thoughts-american-independence.