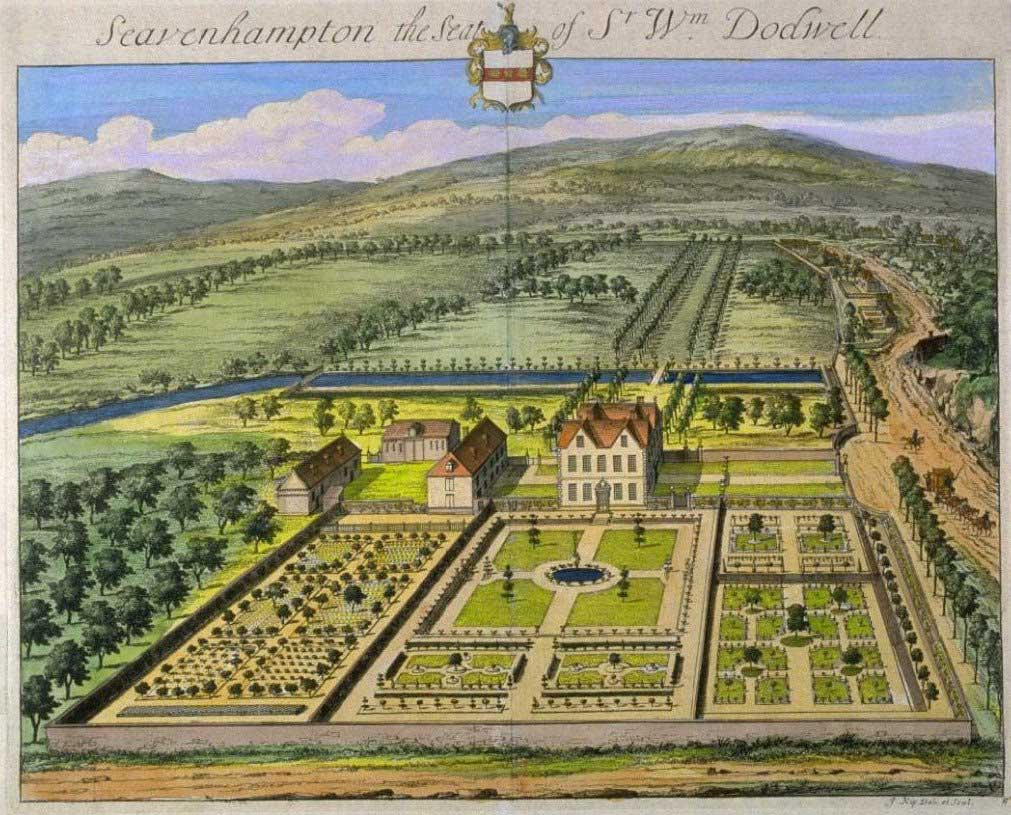

This winter, while battling the ice and snow at the Custis Square archaeological site, we made some incredible discoveries that have helped us reconstruct the layout of John Custis IV’s early 18th-century garden. When Custis first began laying out his garden in the 1710s or early 1720s, large geometric pleasure gardens were just starting to become fashionable amongst members of the British gentry. For the movers and shakers of early 18th century English society, laying out ornamental gardens with carefully manicured planting beds and symmetrically aligned shrubs at their country estates was almost as important as collecting artwork to hang in their manor houses (Fig. 1). Proper gardening was a way of showing off one’s wealth and taste. Numerous tomes were published describing the correct geometric angles and ratios, often derived from classical Roman and Greek architecture, for gentlemen gardeners to use when designing their gardens. While some of these gardeners wrote extensively about their garden layouts, Custis’ surviving letters rarely mention the subject. The main focus of Custis’ letters is the plants themselves and the appropriate way of growing them, not how they should be placed in his garden. Therefore, one of the questions we set out to answer during the archaeological excavations was how exactly the gardens at Custis Square were laid out.

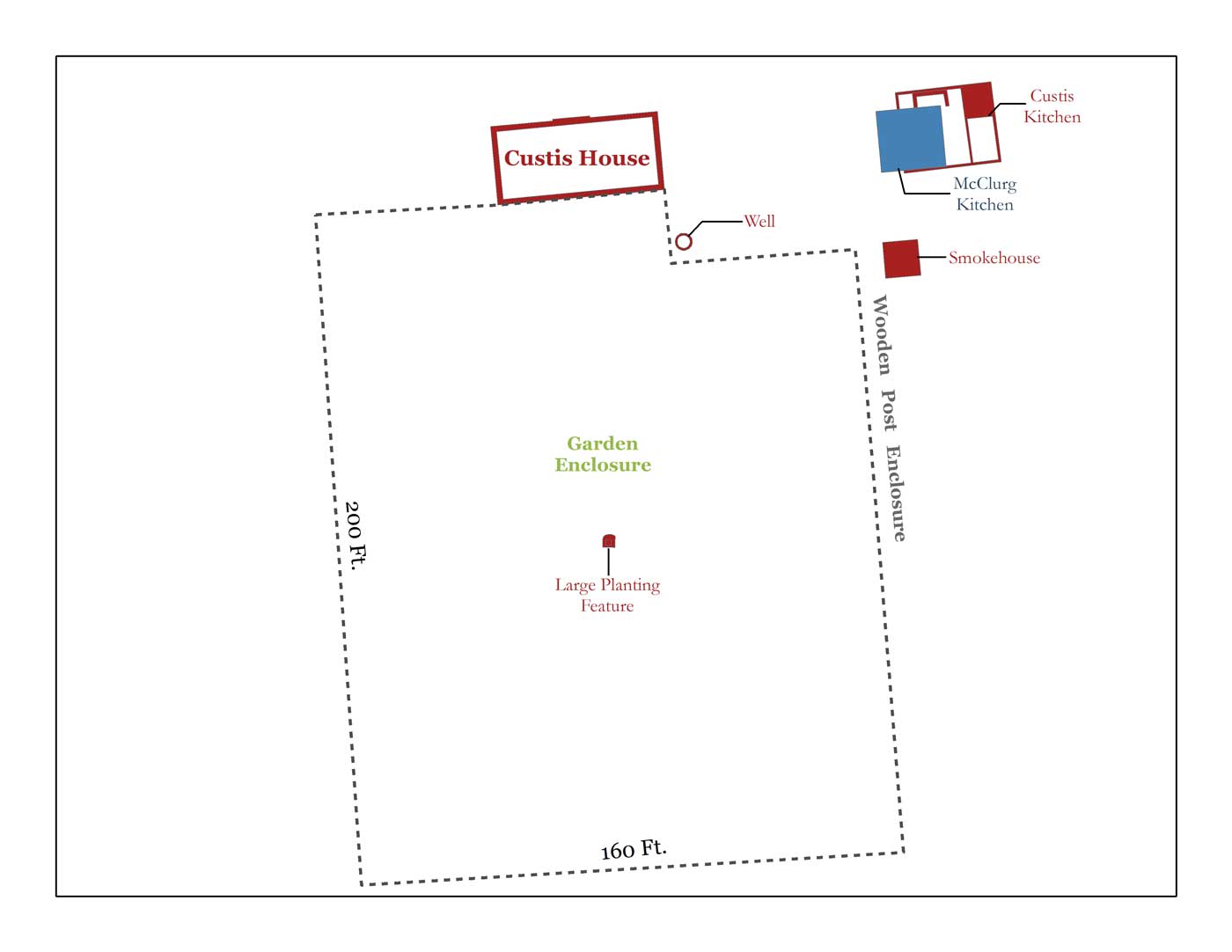

Over the last year, we have been able to determine that, soon after Custis finished building the large brick house at Custis Square circa 1715, he had a large wooden fence constructed around a 160-foot by 200-foot enclosure directly behind the manor. Once we confirmed the dimensions of this garden enclosure, we decided to dig directly in the center to see if there was anything to mark the middle of the garden. Lo and behold, we found a large planting hole! The feature was larger than any other garden planting we have found so far and was placed exactly in the center of the enclosure. The more we excavate, the more certain we are that Custis’ garden was laid out in a fashionable geometric pattern centered around a large tree or shrub located in the center of the garden enclosure (Fig. 2).

While many English aristocrats got the inspiration for their garden layouts from books, it became more and more common over the course of the 18th century to hire a professional gardener when designing an ornamental garden. These men would help landowners design and construct their gardens, procure plants from greenhouses, and coordinate the pruning, watering, and maintenance required to keep the garden in good shape. While we have plenty of documentary evidence that Custis purchased his own plants and ordered his enslaved laborers to maintain his garden, it is quite possible that he hired a gardener to help with the design of his garden. If so, Custis most likely acquired the services of a man named Thomas Crease, his neighbor and the only professional gardener known to have resided in Williamsburg in the early 18th century.

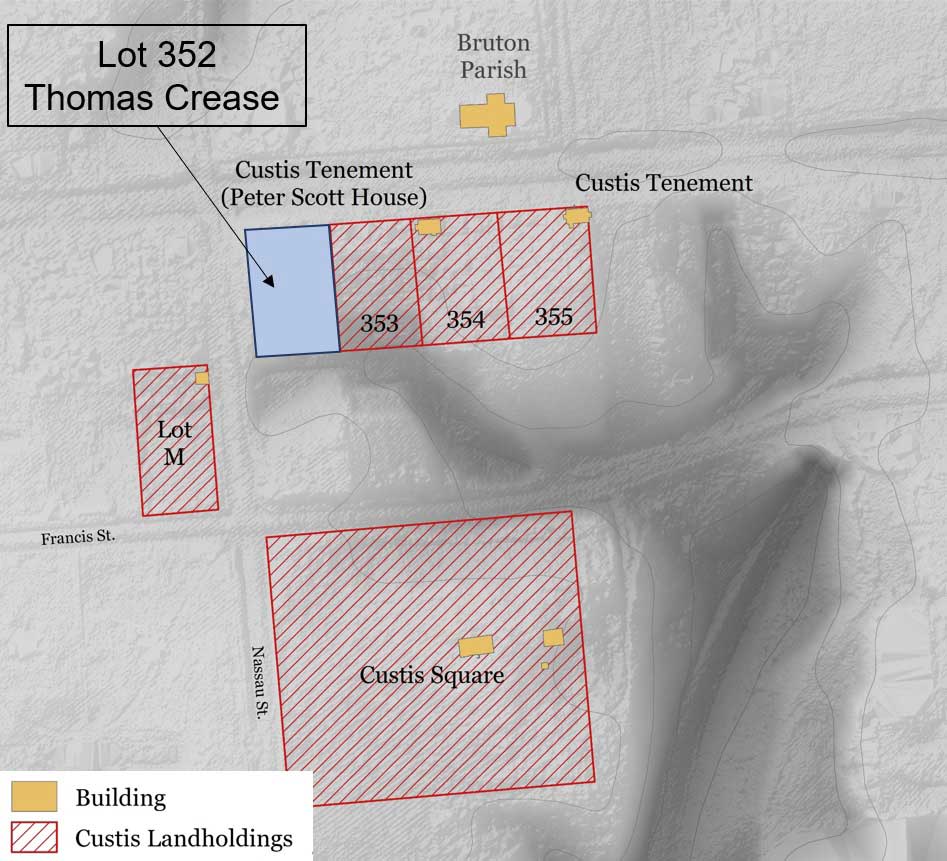

We don’t yet know where Thomas Crease was born or where he received his training, but we do know that he was in Virginia and working as a gardener at William Byrd II’s plantation at Westover by the second decade of the 18th century. By the time William Byrd II returned to Virginia from England in February 1720, Crease had left his service and was living in Williamsburg. However, Crease visited Westover several times to help plan an extension to the garden, and one time he brought a letter with him from Byrd’s brother-in-law, who was...you guessed it… John Custis IV! Thomas Crease lived on Lot 352 in Williamsburg, less than a block from Custis Square, for at least 25 years and must have at least known John Custis socially since he delivered letters for him. Beginning in 1726, Thomas Crease was hired as a gardener at the College of William and Mary, a position he held until about 1738. Moreover, he did extensive work on the gardens at the Governor’s Palace in the 1720s and 30s. In addition to working as a gardener, Crease sold plants out of his home, and by the time of his death in 1756, his estate was valued at more than 166 pounds, putting him comfortably within Williamsburg’s middle-class residents. While no written documents survive which indicate that Custis hired Crease to design his garden, there is a strong possibility that he at least consulted with the gardener, given the connections between the two men. Indeed, if Custis was not particularly interested in the garden layout, as his writings suggest, then the geometric patterns that we are beginning to uncover in the soil may have begun as the brainchild of Thomas Crease. Stay tuned as we continue digging into this and other documentary evidence of the garden at Custis Square!

Eric Schweickart is a Staff Archaeologist with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Eric has an MA in Historical Archaeology from the University of Leicester and a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His research focuses on consumerism and household economics in the North Atlantic in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Eric has excavated archaeological sites across the southeastern U.S. over the last decade, including Sapelo Island, Georgia, the Montpelier Plantation in the Virginia Piedmont, and the Coan Hall site on the Northern Neck of Virginia.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.