A few days later, the House of Burgesses voted for her to continue as the public printer for Virginia. It’s a good thing they didn’t wait. Moments before taking up the matter of the public printer, the House of Burgesses voted to set aside a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer in recognition of the closing of Boston harbor. Two days later, Governor Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in response.7

During this moment of crisis, Rind was responsible for printing one of the most radical texts that Virginia had yet seen. In July 1774, Thomas Jefferson set out for Williamsburg to join an extralegal meeting of delegates at what would become known as the First Virginia Convention. But while traveling, an attack of dysentery sent Jefferson home. Having prepared a set of resolutions for the convention, he sent copies of them ahead to Peyton Randolph and Patrick Henry. As Jefferson later recounted in his Autobiography, Henry didn’t do anything with his copy, either because he disapproved of their sentiments or because “he was too lazy to read it (for he was the laziest man in reading I ever knew).”8 But Randolph shared the resolutions with other delegates. While some appreciated them, others felt that they went too far.

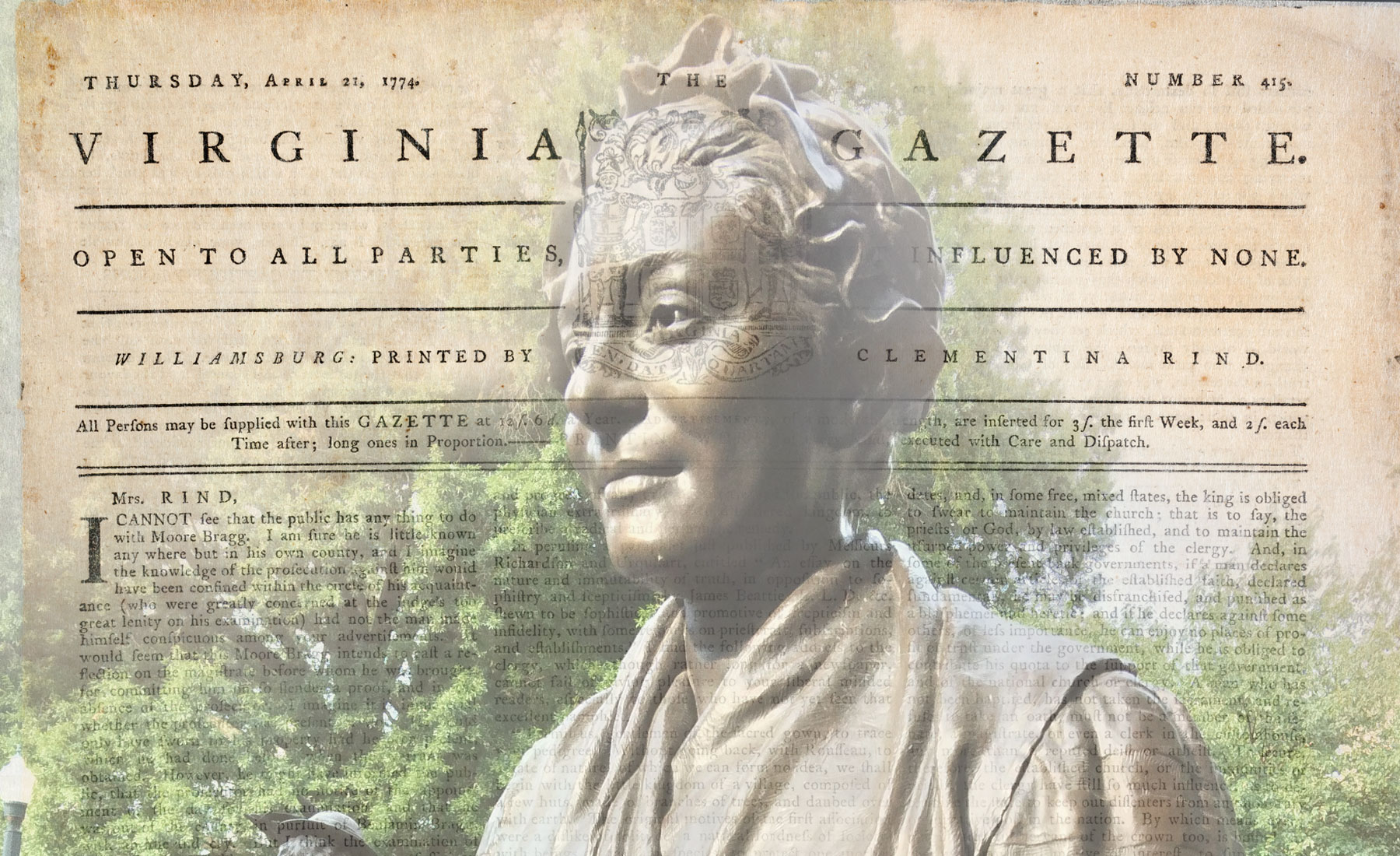

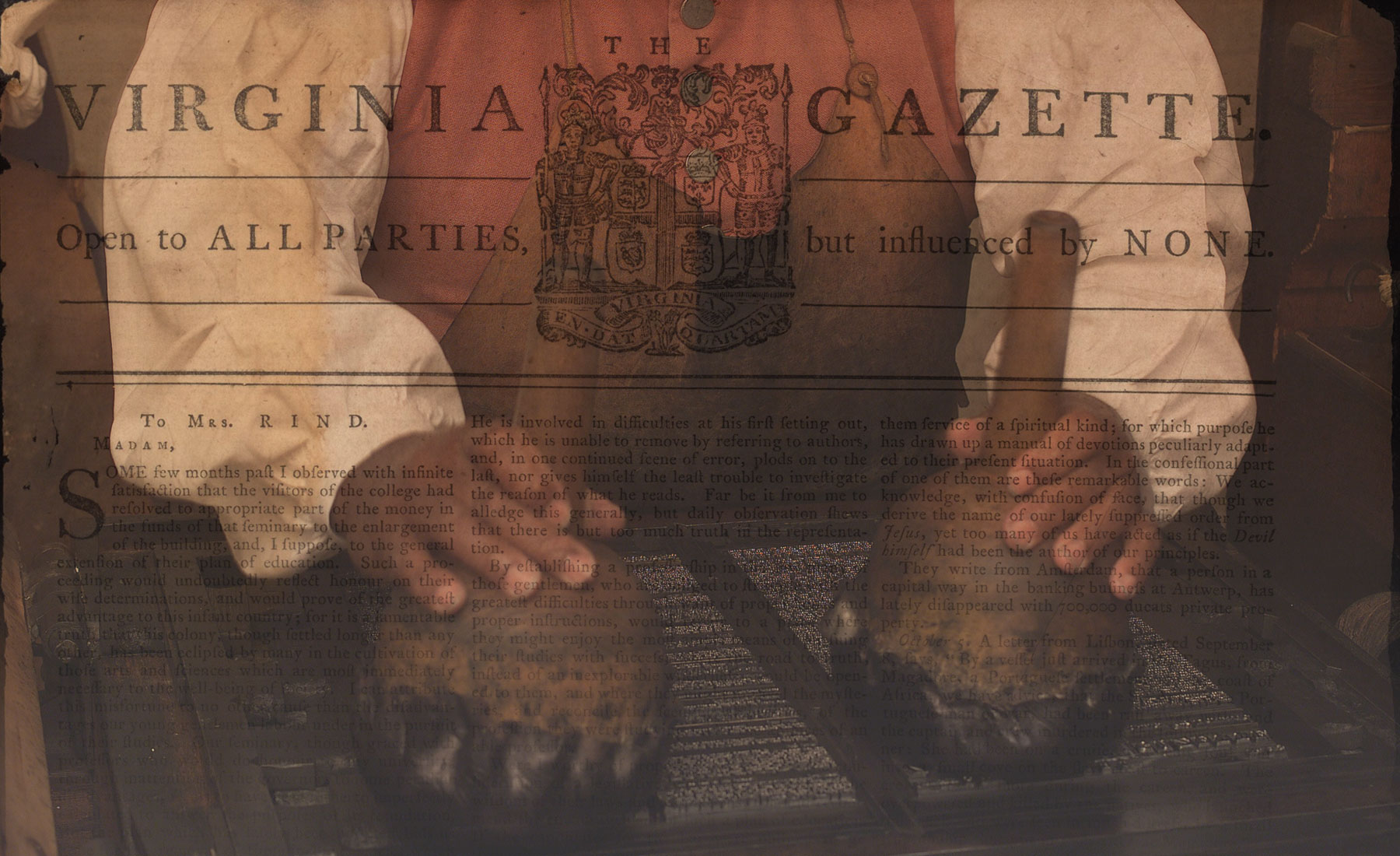

As a result, the more radical delegates took Jefferson’s drafted resolutions to Clementina Rind. On August 8, shortly after the convention closed, Rind published the resolutions as a pamphlet titled A Summary View of the Rights of British America. It rejected Parliament’s authority and insisted that the King was their only legitimate ruler in Britain. Though it was published anonymously, Jefferson believed his authorship of it caused Parliament to consider punishing him.9 If Jefferson was taking a risk by circulating this revolutionary text, Rind took an equal risk in publishing it.