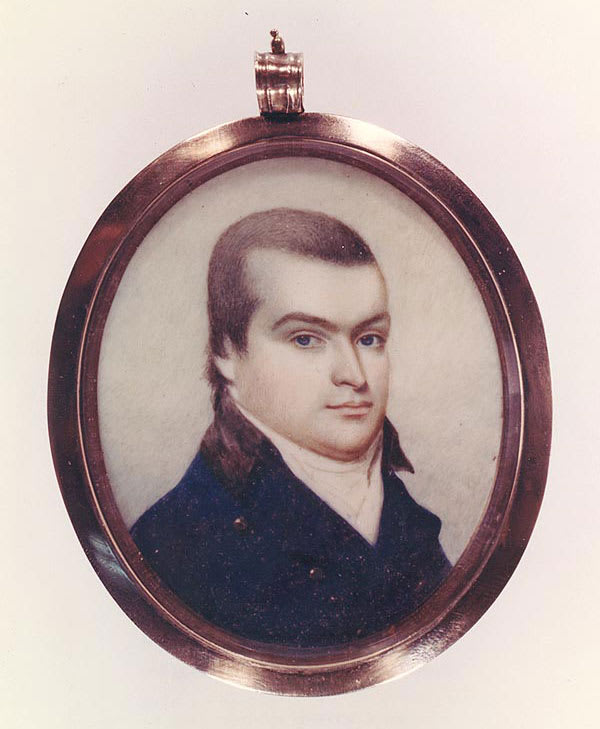

Years before his exploits made him a “Father of the U.S. Navy,” John Barry was a simple merchant captain who passed through Williamsburg on business.

John Barry was born in 1745 to James and Ellen Barry, a poor tenant farming couple in County Wexford, Ireland. After his parents had been evicted from one farm and relocated to Rosslare, nine-year-old John went to sea as a cabin boy for his uncle Nicholas. In the years that followed, John Barry learned the skills necessary to become a merchant captain. By the time he was fifteen years old, Barry made his home in Philadelphia, where he was first hired as a ship captain in 1766. As his reputation as a steady, dependable ship captain grew and his financial prospects improved along with it, Barry soon aspired to owning his own ship.

In August of 1771, Barry partnered with fellow Irishmen John Dugan and Stephen Barden to purchase the vessel Nancy. She was registered as a schooner of 45 tons burden: a schooner designed in Marblehead of similar capacity measured forty-one feet long on deck, 31 feet at her keel, fourteen feet nine inches across at her widest, and a hold just over three feet deep. She was rechristened Industry and left Philadelphia on August 28 under Barry’s command for Virginia’s James River. Industry entered the Chesapeake Bay on the 31st and came to anchor about 9 p.m. in the vicinity of Newport News, after letting a passenger named King ashore. At 1 p.m. on September 1, Industry anchored near Burwell’s Landing, and Barry “Went up to Williamsburg Could Do No Businis.” He had come into town on a Sunday.

Captain Barry had come to Williamsburg to declare Industry and her cargo at the local Custom House and pay the appropriate duties. Despite being some four miles up the Quarterpath Road from Burwell’s Landing, captains of all ships that entered or left the Upper James River District (which extended west from Lyons/Lawnes Creek) were required by law to make the same visit. About 100 vessels cleared the district in 1771, though the vast majority did the bulk of their business beyond Bermuda Hundred, some 55 miles west of Williamsburg. Despite the benefits to consumers in the region and what could likely have been a decrease in local smuggling, Governor Botetourt and the House of Burgesses denied an appeal by merchants near Bermuda Hundred to move the Custom House farther west. As it was, Barry returned to Williamsburg on the September 2, duly entered the Industry at the Custom House (the exact location of which remains unknown), and sailed another 30 miles upriver before anchoring that night.

The following day, Industry anchored abreast of Westover, the plantation of Colonel William Byrd III. Early on the morning of September 4, Industry briefly went aground in the shallows, but eventually passed Bermuda Hundred and anchored again “abreast of Robert Pleasants,” likely the plantation at Curles. On September 5, the schooner arrived at a wharf owned by Thomas Pleasants, Jr. (a merchant who also owned property in Goochland County), where her crew’s efforts to unload their cargo was hampered by rain and foul weather for the next two days.

Sadly, Captain Barry’s cargo manifest has been lost, but a ledger describing the North American coastal trade from 1772 offered some reasonable suggestions. At the time, Philadelphia was exporting these goods that were being received in the Upper James River: common apples, beer and cider, spermaceti candles, coffee, chocolate, wagons, chaises, flax, chairs, iron (in bar, pig, and wrought form), leather, molasses, paper, pasteboard, pimento, cheese, dried and pickled fish, rice, rum (over 88% of which was produced in New England), sugar, salt, shoes, soap, calfskin, wine, staves, pine boards, axes, and scythes. Naturally, Industry could not have carried ALL these goods in a profitable quantity, but Barry could have been advised by his partners in Philadelphia or perhaps through prior correspondence with Thomas Pleasants would have been most likely to sell.

By the end of the day on September 7, Industry’s crew was ready to load the schooner for the trip home. Goods exported from the Upper James River and imported at Philadelphia weren’t nearly as numerous. As one would expect, the district exported tobacco, but also corn, rye, wheat, hemp, lard, pitch, oakum, butter, peas, and dressed deerskin. On September 8, Industry unfurled her sails and got underway, Barry recording the weather as “Cloudy but no Rain.” Unfortunately, the weather did not hold and delayed Industry’s return to Philadelphia until September 21.

John Barry continued as a merchant captain for several more years, sailing ships he had a partial ownership in as well as those owned by prominent Philadelphia businessman Robert Morris. On one such voyage as captain of the Black Prince, John Barry recorded the fastest known day of sailing in the eighteenth century: 237 miles in 24 hours. Barry returned to Virginia in command of the Continental Navy brigantine Lexington, with which he captured HMS Edward on April 7, 1776. John Barry became one of the most celebrated captains in the Continental Navy, best known for his command of the frigate Alliance during the last days of the American Revolution. On June 6, 1794, he accepted his appointment as a captain in the new United States Navy. Along with John Paul Jones and John Adams, John Barry is referred to as a “Father of the United States Navy,” but in 1771, he was just another merchant captain who passed through Williamsburg on business.

Michael Romero is a Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter working in both Orientation and Public Sites. Since 2016, he has been working to bring 18th-century naval history to life. Michael has published work in Naval History magazine and NAI’s Legacy, and is working toward a Master’s Degree in Military History from American Public University.

For Further Reading

- A Complete List of Ships Engaged in American Trade, January 5, 1772-January 6, 1773, With Kind, Tonnage, and Details of Voyages, and a List of Imports and Exports; of the Colonies (With Quantities) for the Same Period. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

- Barry, John. “A Journal of a Voyage from Philadelphia to James River Virginia in the Good Schooner Industry, John Barry, Master.” The John Barry Papers, Library of Congress.

- Frese, Joseph. “The Royal Customs Service in the Chesapeake, 1770: The Reports of John Williams, Inspector General.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 81, no. 3 (July 1973), pp. 280-318.

- McGrath, Tim. John Barry: An American Hero in the Age of Sail. Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2010.