Distant whistles and whoops quieted the crowd. Something was happening outside.

It was a cold December evening. Thousands of Bostonians had assembled in a town meeting to discuss what to do about the tea. Hoping to save the insolvent East India Company, Parliament had passed the Tea Act. This law lowered taxes on tea and sent shiploads to the colonies, including Boston. The Tea Act would also reduce competition by strengthening customs enforcement, limiting the amount of Dutch tea smuggled into the colonies.

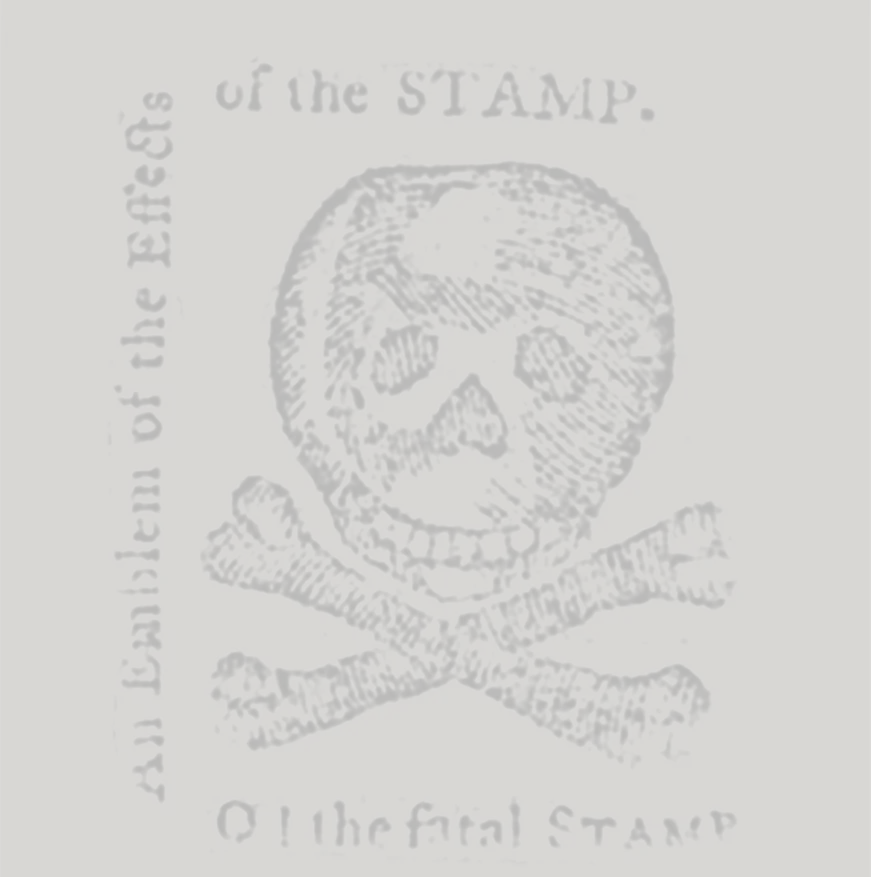

Many Bostonians viewed this as an act of tyranny. They would not allow the tea to land. But during the meeting, word arrived that the governor also refused to allow the tea-bearing ships to leave peacefully and return to Britain. It was a crisis—a standoff.

Minutes later, a group of men wearing costumes meant to resemble Native people stormed the meeting. Thousands of people followed them down to the wharf as the “Mohawks” boarded the tea ships and dumped the tea in the harbor.

Most Americans know the story of the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773. Many love it. But there's one perplexing detail. Why did they dress like Native people?

“to resemble Indians”: What did they look like?

Since everyone made their own costume, appearances varied. Some participants planned their costumes. Others improvised them on a few minutes’ notice. When a young man named Joshua Wyeth described dressing “to resemble Indians,” he added the telling qualification, “as much as possible.”1

Almost all accounts mention that the men painted their faces black, red, or copper. Witnesses and participants recalled faces smeared with paint, lampblack, charcoal, grease, coal dust, burnt cork, and red ochre. They used whatever was on hand, and sometimes whatever they could find in a nearby shop.2 For some participants, this was the extent of their costume. According to one, “none of the party were painted as Indians, nor, that I know of disguised, excepting that some of them stopped at a paint shop on the way and daubed their faces with paint.”3

Some wore clothing and other accessories. One young boy was instructed to “tie a handkerchief round his frock.”4 Witnesses recalled men dressed in blankets, “old frocks, red woollen caps, gowns, and all manner of like devices.”5 Some were armed. A participant named George Robert Twelves Hewes grabbed a hatchet but called it a tomahawk.6

Given these costumes, it is surprising that witnesses identified the men as “Indians.” But many participants portrayed “Indianness” more through sounds than sights. Bystanders reported whooping, whistling, and use of a mock language echoing stereotypes of Native people.7

Costumes or disguises?

Boston was a small town in 1773, the sort of place where you were always running into people you knew. Even on the dark night of December 16, 1773, it was easy to be recognized. When one Tea Party participant boarded a ship, for example, he saw his future brother-in-law, who was that ship’s mate. He quickly changed to another ship.8

Some tea destroyers feared official punishment.9 Others worried more about their neighbors, friends, and employers. Joshua Wyeth recalled that “not a few” of those dressed as Native people in Boston harbor that night were apprentices, like himself, with “tory [pro-government] masters.” They didn’t want their masters to find out that they had been on the wharf that night. For this, a darkened face was useful. Wyeth recalled that after his group painted their faces, “We should not have known each other, except by our voices.” 10

If the use of costumes protected those wearing them, they may have also helped onlookers. The Sons of Liberty staged the night so that the tea destroyers’ costumes separated them from the people attending the town meeting. Everyone saw that leaders like Samuel Adams and John Hancock were dressed in normal clothes, directing the meeting. They weren't in the harbor breaking open tea chests.11 When the “Indians” stamped and whooped through the town meeting, they seemed like mischievous outsiders. Bostonians, not for the first time, blamed mob violence on outside agitators. 12

Why dress as Native people?

The Boston Tea Party took place in mid-December. Since ancient Rome, many European cultures celebrated that time of year with a lively festive season. Some traditional festivals featured acts of “misrule” and carnival inversions, which turned the world upside down. A person of low status could be temporarily elevated to a high status. Someone might have an opportunity to behave in an unusual way. A pauper could pretend to be a king, and a criminal could be a bishop.13 It was like celebrating Christmas with opposite day.

Colonists continued these traditions in North America. And when they looked for opposites, they often looked to Native people.14

In one sense, colonists saw in Native America the opposite of Europe’s worst excesses. Revolutionary leaders had spent years trying to persuade colonists not to buy British goods like tea. Accumulating luxuries, they argued, would corrupt the people.15 Colonists believed that European decadence had not yet corrupted Native people. At the Boston Tea Party, Patriot leaders may have been drawing on the image of austere, “noble” Natives. By donning Native costumes, the destruction of British tea could become a moral critique of consumerism.

But colonists also saw Native “savagery” as the mirror image of European civility. Since they imagined Native people to be so much more violent than themselves, the Boston Tea Party costumes may have carried a threat. The colonists might be orderly and obedient, they seemed to say, but the Mohawks were not. Peter Oliver, a leading Loyalist, claimed that the colonists needed to “make their Agents first look like the Devil, in Order to make them Act like the Devil.”16

Colonists had previously dressed as Native people while protesting unpopular laws.17 This accelerated during the revolution. Britons and Americans used the likeness of Native people to depict the rebellious colonists in scores of cartoons, newspaper essays, prints, newspapers, songs, handbills, and flags.18 The destruction of the tea in Boston was only the most memorable example of this pattern.

Did they dress as Mohawks?

It is not clear that the leaders behind the Boston Tea Party intended for the participants to represent a particular Native group. Some thought that the costumes represented Narragansett people.19 That makes sense, as the Narragansett people lived close to Boston.

But after the event, most colonists and Britons came to describe the protestors as “Mohawks.” The Mohawk people had a reputation as fearsome warriors.2 But they lived several hundred miles from Boston, in New York state. So why did people choose to primarily describe the Boston Tea Party participants as ”Mohawks,” rather than Narragansett people?

New York colonists, who lived closer to the Mohawk people, were already using the identity of Mohawks during the conflict with Britain.21 Some of this roleplay leaked north. Three days before the Tea Party, a Boston newspaper republished a piece from a New York City newspaper signed by “The Mohawks.” It promised that the Mohawks would make “an unwelcome visit” to whoever assisted with the British government’s plan for tea imports.22 This sensational essay may have been on peoples’ minds in the aftermath of the Tea Party.

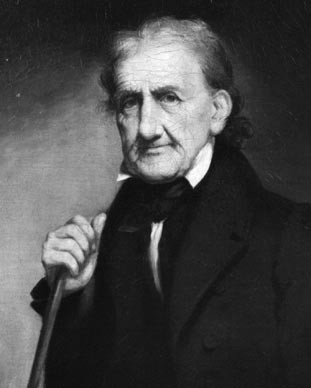

For at least one New England Loyalist, the name “Mohawk” also evoked violent lawlessness. Massachusetts’ Chief Justice Peter Oliver later wrote that at the time of the Tea Party, the Boston town meeting contained a group of “Mohawks & Hawcubites” who worked with Patriot leaders.23 This was a reference to a street gang from decades earlier called the “Mohocks and Hawkubites.” Named for the American tribe, this gang stirred an uproar that long outlasted it. In Oliver’s account, the “Mohawk” label suggested that the Boston Patriots were not colonists nor Natives, but rather a gang of thugs.24

Further reading

SOURCES

Header image: W. D. Cooper, “Boston Tea Party,” engraving (1789). Library of Congress.

- “Revolutionary Reminiscence of Throwing the Tea Overboard in Boston Harbour,” Western Monthly Review, volume 1 (Cincinnati: E. H. Flint, 1828), 148.

- Francis S. Drake, Tea leaves; being a collection of letters and documents relating to the shipment of tea to the American colonies in the year 1773, by the East India Tea Company (Boston: A. O. Crane, 1884), clix, 92–93; Revolutionary Reminiscence,” 148; James Hawkes, A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party, with a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (New York: Bliss: 1834), 38.

- “Ebenezer Stevens: Lieut.-Col. Of Artillery in the Continental Army,” The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries, vol. 1 (New York: A. S. Barnes & Company, 1877), 590. See also account of Benjamin Simpson in George Folsom, History of Saco and Biddeford (Saco: Alex C. Putnam, 1830), 288n.

- “Deaths,” Newburyport Herald, Oct. 18, 1831.

- Winthrop Sargent, ed., “Letters of John Andrews, Esq., of Boston,” in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 8: 1864–1865 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, Wiggin and Lunt, 1865), 326; Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, vol. 4: 1749 to 1774 (London: John Murray, 1828), 436; Benjamin Bussey Thatcher, Traits of the Tea Party: Being a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), 181.

- James Hawkes, A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party, with a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (New York: Bliss: 1834), 38.

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 141–42.

- “Ebenezer Stevens,” 590.

- Benjamin Carp notes that sentries were posted to warn about the approach of authorities. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 128.

- “Revolutionary Reminiscence,” 148.

- Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 122, 125.

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 143, 145–46.

- Natalie Zemon Davis, “The Reasons of Misrule: Youth Groups and Charivaris in Sixteenth-Century France,” Past & Present 50 (Feb. 1971): 41-75; Marc Jacobs, “King for a Day. Games of Inversion, Representation, and Appropriation in Ancient Regime Europe,” in Mystifying the Monarch: Studies on Discourse, Power, and History, ed. Jeroen Deploige and Gita Deneckere (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), 117–38.

- Stephen Nissenbaum, The Battle for Christmas: A Cultural History of America’s Most Cherished Holiday (New York: Vintage, 1996), 5–6; Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 10–12.

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 59–65; T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (Oxford: 2004), ch. 5.

- Peter Oliver, Peter Oliver’s Origin & progress of the American rebellion: a Tory view ed. Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967), 103.

- Deloria, Playing Indian, ch. 1; Alan Leander MacGregor, “Tammany: The Indian as Rhetorical Surrogate,” American Quarterly 35 (Autumn 1983): 396–97.

- Deloria, Playing Indian, 29–32; Lester C. Olson, “The Colonies Are an Indian,” in Emblems of American community in the revolutionary era: a study in rhetorical iconology (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 75–123; Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 157.

- Sargent, ed., “Letters of John Andrews, Esq., of Boston.”

- Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 146–50.

- Deloria, Playing Indian, 12–13; J. L. Bell, “How ‘Mohawk’ Conquered ‘Narragansett’ in Reports of the Boston Tea Party,” Boston 1775, Dec. 19, 2016; J. L. Bell, “The Appearance of the Mohawks,” Boston 1775, Dec. 16, 2016; MacGregor, “Tammany,” 396–97.

- “New York, Dec. 6, 1773,” Boston Post-Boy, Dec. 6, 1773. Quoted in Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 158.

- Oliver, Peter Oliver’s Origin & progress of the American rebellion, 110.

- Roger D. Abrahams, “Mohawks, Mohocks, Hawkubites, Whatever,” Common-place 8 (July 2008).