[Note: this page reproduces eighteenth-century sources describing violence against enslaved people and containing racist language.]

We don’t know much about Aaron Griffin. We know that he was an enslaved man living in Virginia. We know that he escaped slavery at least five times between 1767 and 1770. We also know that in October 1770, he sued his enslaver Henry Randolph for his freedom.

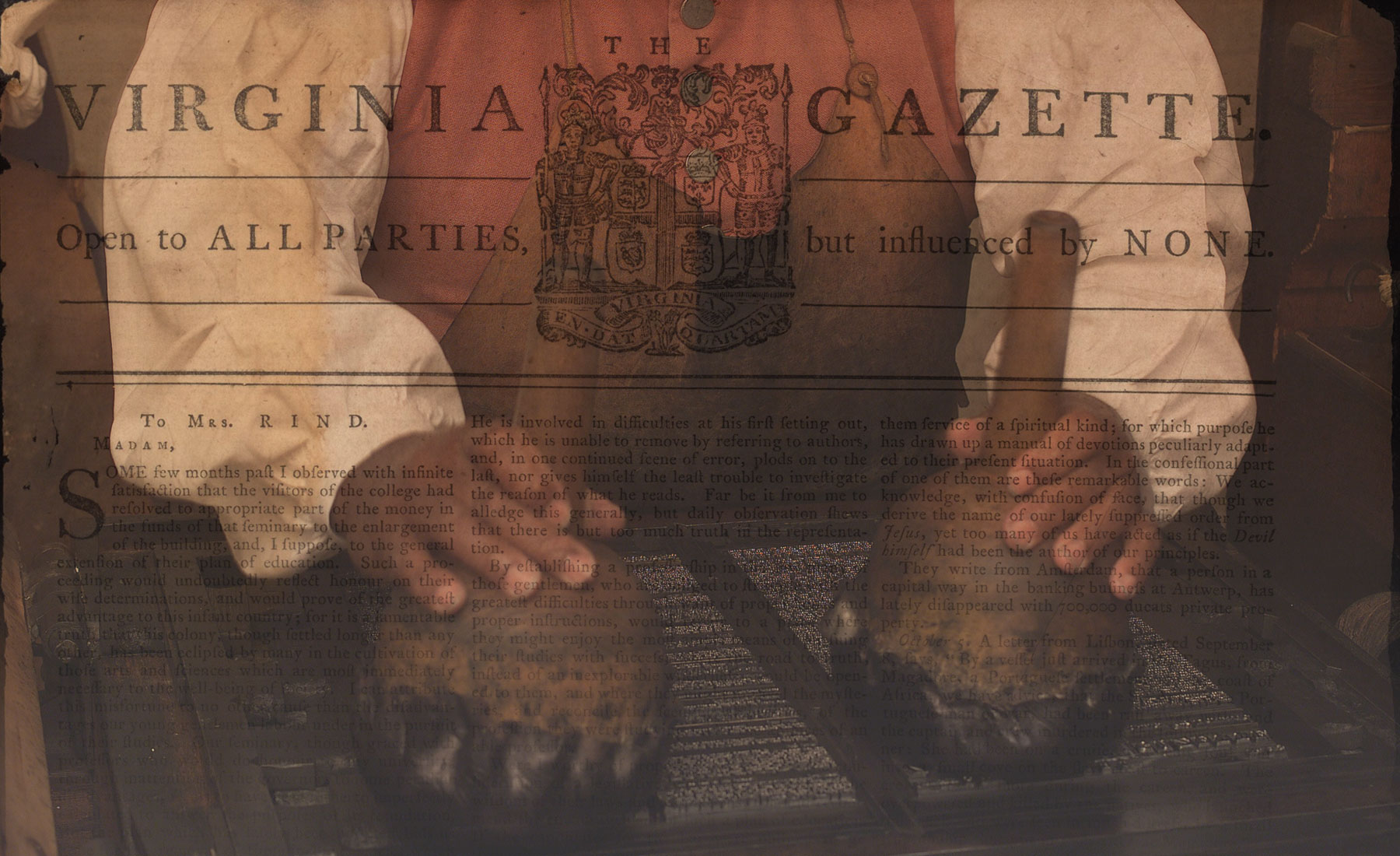

Little as this is, it is more than we know about most enslaved people in eighteenth-century America. The outlines of Griffin’s story are only available to us because Randolph repeatedly described Griffin and his escape attempts in the pages of the Virginia Gazette. In brief “runaway” advertisements, Randolph provided information that would help to recover Griffin. But he also provided a tiny window onto Aaron Griffin’s search for the dim light of freedom in a world of bondage.

Escaping Bondage

Griffin’s first escape from slavery occurred in the months following a violent incident at Randolph’s plantation. On July 27, 1767, according to county court records, Henry Randolph killed an enslaved man named Len. The court heard testimony about this and decided not to prosecute Randolph.1 The record provides no further detail about this incident. But Griffin’s first escape attempt happened sometime in the next few months.

According to an advertisement published in December 1767, Griffin was a teenager when he first attempted to escape slavery. He was nearly six feet tall. The advertisement indicates that Griffin’s cheeks were branded with the letters “IR.” Enslavers sometimes branded the flesh of enslaved people, especially when they committed crimes or resisted their enslavement.2 Over time, Griffin’s scar faded. Later advertisements describe the mark as “not very plain,” then “not plain,” “almost worn out,” and finally “very dull.” As the brand faded, Griffin’s features probably drew less suspicion.

Randolph quickly apprehended Griffin following his first escape. We know this because Randolph later placed a notice indicating that he had escaped again only a few days after the first advertisement had been published.

Sometime between April and October 1768, Randolph again captured Aaron. He ran away again on October 13, 1768. A year later, Henry’s son John placed an advertisement seeking Griffin again. He had escaped with another enslaved man named Sam.

Suing for Freedom

June 30, 1770, Griffin escaped again. The Randolphs had apparently apprehended Griffin after each of his escape attempts. He shifted tactics. Still out of his enslaver’s grasp, Griffin sued Henry Randolph for his freedom in October 1770. He would have pled his case at the General Court in the Williamsburg Capitol. Unfortunately, the records for this case, and many others, were destroyed in a fire. We know only that Griffin lost. 3

Only one detailed account of a freedom suit survives from this era. In 1772, the distinguished lawyer George Mason successfully sued for the freedom of a dozen enslaved plaintiffs who were descendants of a free Native woman. Thomas Jefferson, a young lawyer, took notes. According to Jefferson’s account, Mason pointed out that the colony’s laws stated that if a mother was free, her child should be free. But since Virginia had effectively outlawed the enslavement of Native people, Mason argued, his plaintiffs should be free because they had an indigenous mother.4

Griffin was one of many enslaved Virginians seeking freedom through the court system. The advertisement seeking Griffin after his fifth self-emancipation noted that “many of his Colour got their Freedom” recently in court.5 And Jefferson recorded Mason claiming that “hundreds of the descendants of Indians have obtained their freedom, on actions brought in this court.”6 Griffin might have used a legal argument similar to the one that Mason later made. Randolph’s advertisements had consistently described Griffin as a “Mulatto fellow” or as having a “yellow complexion,” which suggested that he might have had a combination of African with European or Native ancestry. 7

It is unclear why Aaron Griffin’s freedom suit failed while others succeeded. Perhaps he lacked a lawyer as skilled as Mason. Perhaps he was unable to substantiate his parentage. But a couple of months after Henry Randolph won the court case, his son John Randolph placed a final advertisement seeking Griffin.

In his first advertisement for Griffin, Randolph had offered 40 shillings for his capture. The next three ads offered five pounds. The fifth advertisement sought a different outcome. There would be no more escapes. According to Virginia law, if the civil authority “outlawed” an escaped enslaved person, a sheriff would be directed to apprehend them and any white citizen could legally kill them.8 In this advertisement, Randolph indicated that Griffin had been “outlawed,” and offered five pounds for Griffin’s capture or ten pounds for “his Head.”

We don’t know the end of Aaron Griffin’s story. He disappears from the documentary record at this point. He may have found freedom. He may have been captured or killed. It is unlikely that we will ever know much more. While advertisements like these in the Virginia Gazette offer important insights into the lives of enslaved people like Griffin, they will always raise more questions than they answer. In this case, they reveal only enough for us to glimpse Griffin’s resilience and persistence in seeking freedom.

Learn More

SOURCES

- Chesterfield (VA) County Order Book, No. 4: 1767–1771, p. 55, Family Search.

- Marin L. Michael Kay and Lorin Lee Carey, “Slave Runaways in Colonial North Carolina, 1758–1775,” North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 1 (Jan. 1986): 30; Thomas D. Morris, Southern slavery and the law, 1619–1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 3; Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), 67, 94; Albert H. Tillson Jr., Accommodating Revolutions: Virginia’s Northern Neck in an Era of Transformations, 1760–1810 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 102. See also advertisement of Samuel Sherwin, Virginia Gazette (Rind), May 9, 1771, page 4.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon) Jan. 10, 1771, p. 4 (see below).

- Warren M. Billings, “The Cases of Fernando and Elizabeth Key: A Note on the Status of Blacks in Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” William and Mary Quarterly 30 (July 1973): 467–74; Peter Wallenstein, “Indian Foremothers: Race, Sex, Slavery, and Freedom in Early Virginia," in The Devil's Lane: Sex and Race in the Early South, ed. Catherine Clinton and Michele Gillespie (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) 57–73; Michael L. Nicholls, “‘The squint of freedom’: African-American Freedom Suits in Post-Revolutionary Virginia,” Slavery and Abolition 20 (no. 2, 1999): 47–62; Gregory Ablavsky, “Making Indians ‘White’: The Judicial Abolition of Native Slavery in Revolutionary Virginia and Its Racial Legacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 159, no. 5 (April 2011): 1457–1531; Honor Sachs, “‘Freedom By A Judgment’: The Legal History of an Afro-Indian Family,” Law and History Review 30, no. 1 (Feb. 2012): 173–203. The judgment for this case is available at this Library of Virginia digital exhibit.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon) Jan. 10, 1771, p. 4.

- Thomas Jefferson, Reports of Cases Determined in the General Court of Virginia: From 1730, to 1740; and From 1768, to 1772 (Charlottesville: F. Carr, and Co., 1829), 116.

- Anjali DasSarma and Linford D. Fisher, “The Persistence of Indigenous Unfreedom in Early American Newspaper Advertisements, 1704–1804,” Slavery & Abolition 44 (no. 4, 2023): 270; Sharon Block, Colonial Complexions: Race and Bodies in Eighteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 103–8.

- “An act for suppressing outlying Slaves,” in The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, ed. William Waller Hening (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3:86; Thomas D. Morris, Southern slavery and the law, 1619–1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 341.