Thomas Jefferson debuted as a political pamphleteer in the summer of 1774 because of an unfortunate bout of dysentery.

He had been elected to a convention of Virginia’s revolutionary leaders in Williamsburg. They were meeting to plan a response to what many perceived as an act of tyranny by Parliament: the decision to close Boston harbor following the Boston Tea Party. Jefferson liked to be prepared. He knew the Williamsburg convention would be choosing delegates to send to an intercolonial meeting in Philadelphia. He also knew they would write instructions to guide their representatives’ negotiations with other colonies. Before he left for Williamsburg, Jefferson composed some ideas “which I meant to propose” as those instructions.1

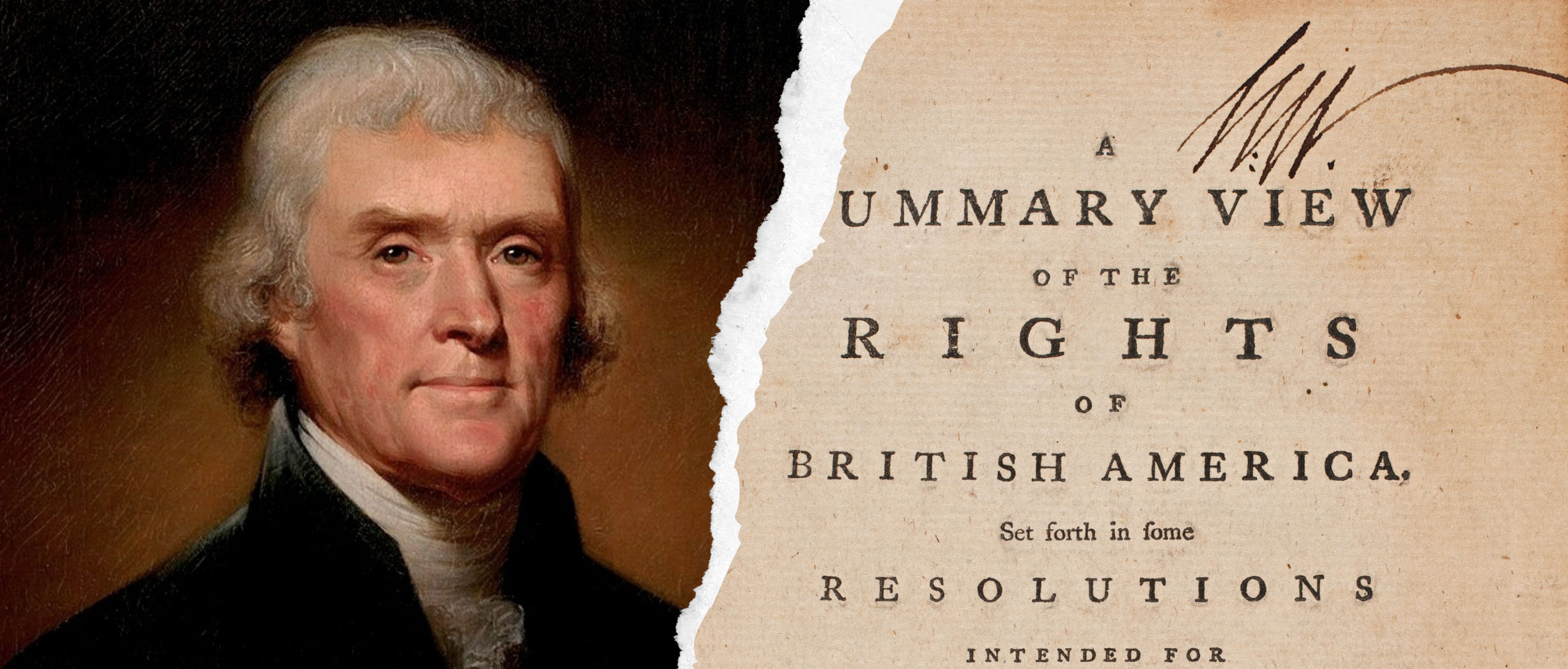

After he fell ill on the road to Williamsburg, he sent his draft ahead in his absence. The convention’s attendees published the draft as an anonymous pamphlet titled A Summary View of the Rights of British America. It laid out several extreme, radical arguments. Indeed, in some of its sentiments and ideas, Jefferson’s A Summary View was a preview of the Declaration of Independence.

The Road to Radicalism

Virginia’s leaders convened amid an escalating ping pong of policies and protests. Parliament had passed the Tea Act in 1773, which restricted how the colonists could import tea. In response, Boston radicals dumped a shipment of tea in their city’s harbor. Parliament answered by punishing Boston and closing their port with the Boston Port Act, the first in a string of laws that the colonists would soon call the Intolerable Acts. When Virginia’s House of Burgesses objected, the colony’s governor dissolved them. And now, lacking a legal body in which to deliberate, the colony’s leaders were meeting on their own authority to plan a response.

Most elite Virginians remained cautious. They objected to the Tea Act and the events that followed. Yet they also admitted that Parliament had the right to regulate their trade. A popular essay series by Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson had argued Parliament could not raise direct taxes but had the right to tax the colonies’ trade. A few radicals to the north had gone further, rejecting Parliamentary authority completely. But in Virginia, few had expressed this opinion. As Jefferson remembered, in the summer of 1774 many of Virginia’s political elites “stopped at the half-way house of John Dickinson.” But Jefferson was ready to renounce Parliament. He wrote that he “had never been able to get any one to agree with me” on this point in Virginia, except for his mentor and law teacher George Wythe.3

Publication

Jefferson committed his radical views about the colony’s relationship with Parliament into writing as proposed instructions to the delegates to the First Continental Congress. But he was unable to propose them at the Williamsburg convention. As he later recalled, he “was taken ill of dysentery on the road,” and turned back. He sent two copies of his drafted resolutions ahead. One copy reached Patrick Henry, “but he communicated it to nobody.” Decades later, Jefferson still didn’t know if Henry had ignored it because he “disapproved the ground taken,” or because he “was too lazy to read it (for he was the laziest man in reading I ever knew).” But Jefferson sent the second copy to Peyton Randolph, who “laid it on the table for perusal” by other members of the convention.4

Many of the delegates at the Williamsburg convention admired Jefferson’s draft. But there was no chance that they could adopt it as their own. Edmund Randolph later wrote of Jefferson’s resolutions, “I distinctly recollect the applause bestowed on the most of them” when they were read. But while “the young” delegates agreed with Jefferson, according to Randolph, the older members “required time for consideration, before they could tread this lofty ground.”5 Jefferson agreed, recalling that his ideas were considered “too bold for the present state of things.”6

Unable to agree to adopt the resolutions, the delegates crowdfunded their publication. George Washington pledged three shillings and nine pence for the publication of what he called “Mr Jefferson’s Bill of Rights.” With a subscription fund ensuring that her expenses would be covered, Clementina Rind published Jefferson’s resolutions, without Jefferson’s knowledge or approval, sometime on or after August 8, 1774, as A Summary View of the Rights of British America.7

A Summary View of A Summary View

The pamphlet begins with the instruction that Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress should prepare “an humble and dutiful address” to King George III. But, he explained, it should not be too humble. It should be “penned in the language of truth,” rather than “expressions of servility,” to convince the king that the colonists sought rights, not favors. King George should expect no more, Jefferson wrote, since he was “no more than the chief officer of the people.”8 It was an uncompromising beginning.

A Summary View made two extraordinary claims. First, it denied that Parliament had any authority over the colonies. When the colonists migrated from Great Britain, Jefferson claimed, they left Parliament behind. It was “individuals,” not “the British public,” who had invaded and conquered North America: “for themselves they fought, for themselves they conquered, and for themselves alone they have right to hold.” While the colonists chose to remain subjects of the British monarchy, Jefferson wrote, Parliament was little more than “a body of men, foreign to our constitutions, and unacknowledged by our laws.”9

Jefferson’s second extraordinary idea was that King George III was partly responsible for the crisis. To this point, colonists had directed their protests against Parliament, rather than the king.10 But Jefferson ended the petition with a detailed list of injustices he charged to the king. The king had vetoed or ignored necessary colonial laws. His representatives had obstructed legislative assemblies. His Proclamation of 1763 had limited colonists’ migration into western lands. And he had sent soldiers to enforce these outrageous decisions.11 The pamphlet concluded with a plea for harmony with the British government, but not compromise: “Let them name their terms, but let them be just.” 12

Impact

While Clementina Rind was preparing Jefferson’s pamphlet for publication, she was also working on the Virginia convention’s official instructions for its delegates to the Continental Congress. Anyone who read both would have noticed the contrasting styles. A Summary View was bold and fiery. As Jefferson wrote, “a free people” should express themselves freely: “Let those flatter, who fear; it is not an American art.”13 The convention’s official instructions were mealy-mouthed and polite, including a lengthy assurance that they “sincerely approve of a constitutional Connexion with Great Britain” and would support “our lawful and rightful Sovereign.”14 Though the official instructions questioned Parliament’s authority and listed many of the same grievances as Jefferson, they avoided outright criticism of King George.

This contrast might have been the point. In a brief preface, the self-appointed “Editors” of A Summary View noted that it had been published to show “the world the moderation of our late convention, who have only touched with tenderness many of the claims insisted on in this pamphlet, though every heart acknowledged their justice.”15 Did Jefferson’s allies publish A Summary View to signal to London that more extreme possibilities awaited? If British leaders ignored the convention’s humble pleas, A Summary View promised more urgent demands.

While many of Jefferson’s political ideas were radical in August 1774, events caught up to them two summers later. In 1776, the Second Continental Congress asked the young Virginian to draft their explanation for why the colonies were leaving the British empire. The document he produced, the Declaration of Independence, shared much with A Summary View. It extended the pamphlet’s focus on the misdeeds of King George III. Each of the grievances about the monarch in A Summary View appeared among the “repeated injuries and usurpations” that Jefferson listed in his draft of the Declaration of Independence. They even appeared in the same order in both documents.16 Moreover, the beliefs Jefferson stated in A Summary View about the colonists’ rights found their fullest expression in the Declaration of Independence’s withdrawal from an imperial relationship. In A Summary View Jefferson helped to lay the intellectual groundwork for the birth of American independence.

Sources

- Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson: 1745–1790, Together with A Summary of the Chief Events in Jefferson’s Life (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1914), 14, link.

- William L. Hedges, “Telling off the King: Jefferson’s ‘Summary View’ as American Fantasy,” Early American Literature 22 (Fall 1987): 166.

- Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 14, link. One Virginian who had earlier rejected Parliament’s authority was Thomson Mason, in his “British American” letters published over the previous two months. See Robert Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 1: Forming Thunderclouds and the First Convention, 1763–1774 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), 169–70.

- Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 14–15, link.

- “Edmund Randolph’s Essay on the Revolutionary History of Virginia 1774–1782,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 43 (July 1935): 216.

- Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, 15, link.

- Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia, 1:242.

- [Thomas Jefferson], A summary view of the rights of British America (Williamsburg: Clementina Rind, 1774), 5. Available at Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/08016823.

- [Jefferson], A summary view, 6, 16.

- Hedges, “Telling off the King,” 168.

- [Jefferson], A summary view, 16–21.

- [Jefferson], A summary view, 23.

- [Jefferson], A summary view, 22.

- Instructions for the deputies appointed to meet in General Congress on the part of this colony (Williamsburg: Clementina Rind, 1774), 1–2.

- [Thomas Jefferson], A summary view of the rights of British America (Williamsburg: Clementina Rind, 1774), [p. 3], Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/08016823.

- Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1997), 112. A Summary View lists the following grievances against King George III: royal vetoes (listed in the Declaration’s first grievance: “He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”), restraining clauses on colonial laws (grievance two: “He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained”), Dunmore’s dissolution of the House of Burgesses (grievance four: “he has dissolved Representative houses repeatedly & continually”), the Proclamation of 1763 (grievance seven: “raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands”), the imposition of British armies in North America (grievance eleven: “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures”), the Administration of Justice Act (grievance thirteen: “He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution”), and preventing Virginia’s efforts to limit the slave trade (in Jefferson’s original draft, the final grievance: “he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere”).