The History and Botany of the Tulip in the Colonial Gardens

Tulip season is a beautiful time in Colonial Williamsburg. But do you know the botany and history behind these spectacular blooms? Here are five things you may not know about tulips from the historic trades colonial gardeners.

1. Tulips can be grown from bulbs or seed

Tulips can be grown from a bulb or a seed, but if you want to plant tulip seeds you will need to be very patient. From the germination of a tulip seed to flowering can be close to seven years, and there is no guarantee how that tulip will look when it flowers. Planting tulips from bulbs is a much surer bet. Each season a tulip plant will form one bulb to replace the one that has just flowered, and, under ideal conditions, it will produce several smaller bulbs called offsets. It might take these small offsets a year or two before they flower, but they are genetically identical to their parent bulb. Offsets are the main way that commercial tulip bulb growers continue to produce more tulips. Growing tulips as perennials in the humid climate of Williamsburg can be a challenge, so in the Colonial Garden we grow our favorite tulips in pots. Once the leaves die back we dig up the finished bulbs and store them safely for replanting in the fall.

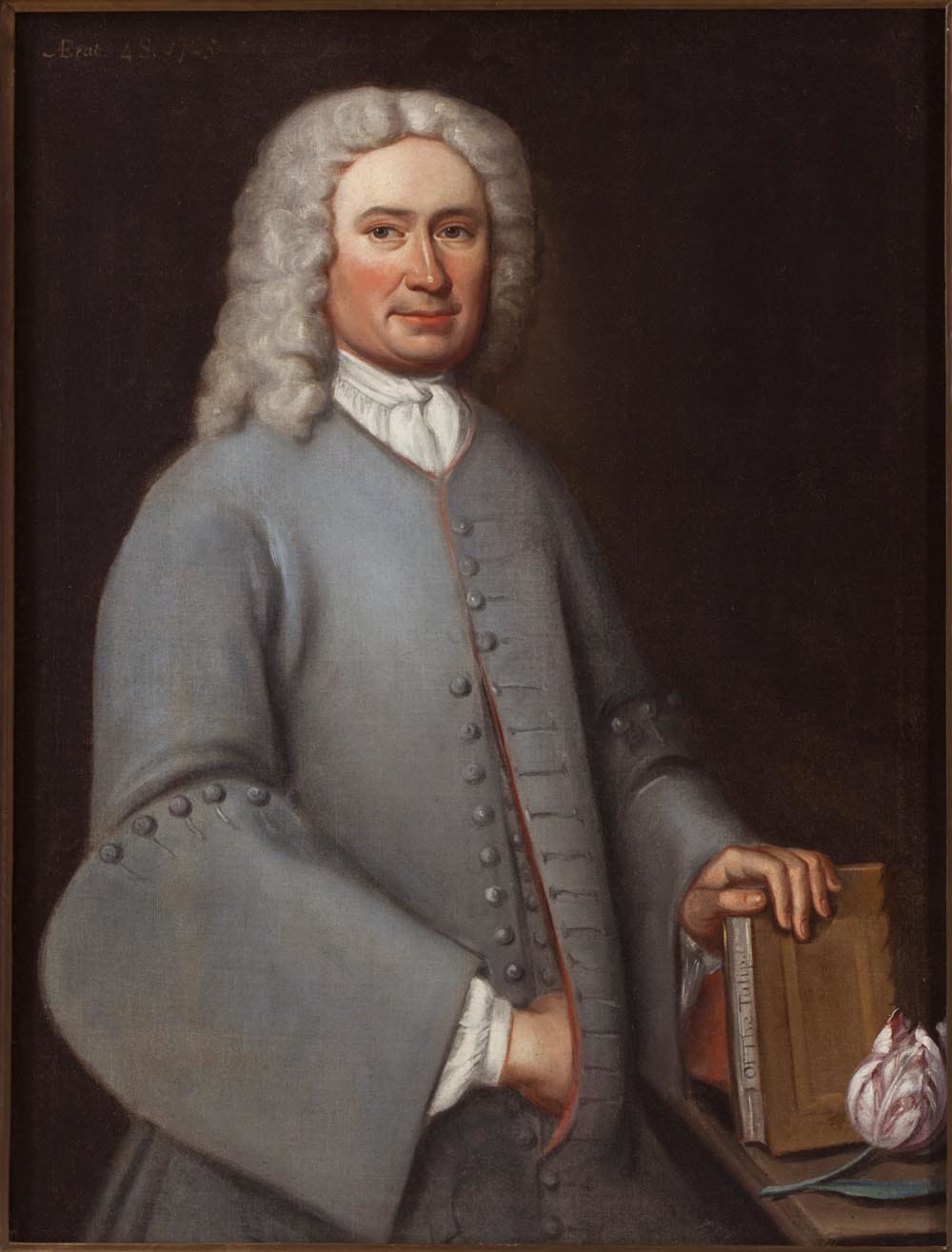

2. John Custis IV loved tulips

John Custis IV purchased property in Williamsburg, Virginia in the first quarter of the 18th century. At his home on the corner of Francis and Nassau streets he established a very fine garden. He grew many flowers, and tulips were surely one of his favorites. In a commissioned portrait of himself, Custis appears holding a book titled On the Tulip, and a red and white striped tulip is sitting before him on a table. From his surviving letters, we know Custis ordered “100 roots of fine double Dutch tulips” from England. To 18th-century gardeners a “double” flower meant one that had more than a single row of petals; these ornate varieties were the height of garden fashion. For many years Custis exchanged letters, seeds, and live plants with the English botanist Peter Collinson. Their letters provide a wealth of information about what plants were grown in early Virginia gardens. In one letter Custis implores Collinson for more tulips, and his obliging friend sends the bulbs. In 1737 Custis writes, “I opened the box immediately; and was very proud to see the tulips fresh and sound.”

3. The beautiful color patterns in tulips are caused by a virus

In the 17th and 18th centuries the most sought-after varieties of tulips were “broken,” with stripes or flames of color on a white or yellow background. Tulip growers at the time had no idea why some formerly solid color tulips would suddenly transform into something rare and beautiful. For a few years in the 1630s, wealthy Dutch merchants became so obsessed with these tulips that they traded them for exorbitant amounts of money. Tulipomania, as it came to be known, didn't last long, but broken tulips remained a prized and sought-after flower. Today we know broken tulips are caused by a virus that infects the plant and is carried to all its successive divisions or offsets. Tulip Breaking Virus causes striking color patterns in the flower, but it also weakens the bulb. Infected bulbs will produce fewer offsets each season and most eventually die. A few varieties have managed to survive despite infection with the virus and can still be purchased. Most striped tulips available today are virus-free, and their color patterns are obtained through very careful breeding. We grow several heirloom broken tulips in pots each season in the Colonial Garden such as Absalon, which has flames of yellow on a burgundy background.

4. Tulips are native to central Asia

The Netherlands may be the largest producer of tulip bulbs today, but central Asia is home to the tulip's wild ancestors. This mountainous region still contains a diversity of wild tulip species in a spectacular array of colors and petal shapes. Tulips were brought to Europe in the sixteenth century from Turkey, where they were already a cherished ornamental flower. Most tulips grown in modern gardens are hybrids of several wild tulip species, but varieties very close to their wild forms are also available. These “botanical” or “species” tulips are often more resilient than modern hybrids and will continue to multiply and return each year. In the colonial garden we grow two botanical tulips: Tulipa clusiana, sometimes called Lady Jane, and Tulipa sylvestris known as the Florentine or woodland tulip.

5. In 18th-century America, tulips were grown in gardens large and small

Since their introduction into gardens, tulips have remained a beloved spring flower. Thomas Jefferson mentioned tulips more than any other flower in his Garden Book, and he ordered bulbs from multiple sources to be planted at Monticello. However, a large estate wasn't required to show off your tulips; William Faris grew tulips in his modest town garden in Annapolis, MD. An Innkeeper, clockmaker and silversmith by trade, Farris had an impressive collection of tulips in his garden. His diary entries survive for 1792-1804, and each year he records how many tulips bloomed. The numbers range from 1,490 to 3,945 bulbs. Faris also sold tulips from his garden. Customers would visit his garden while the flowers were in full bloom and mark a particular tulip they admired with a uniquely notched or painted stick. Once the tulip was finished for the season, he would dig up the bulb to send to its new home.

Teal Brooks is an Apprentice Gardener in the Historic Trades Department at Colonial Williamsburg. She started in her current position in 2017 and began working with the foundation in 2015. She holds a bachelor's degree from The Evergreen State College where she studied sustainable agriculture. When not working in the garden she enjoys cooking, auto repair, and going on adventures with her dog, Rico.

Sources

Botschantzeva, Z. P. Tulips: Taxonomy, Morphology, Cytology, Phytogeography, and Physiology. Translated by H. Q. Varekamp. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema, 1982.

Jefferson, Thomas. Thomas Jefferson's Garden Book, 1766-1824 With Relevant Extracts from His Other Writings, annotated by Edwin Morris Betts. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1944.

Pavord, Anna. Tulip: The Story of a Flower That has Made Men Mad. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

Sarudy, Barbara Wells. “The Gardens and Grounds of an Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Craftsman.” Master's Thesis, University of MD, 1988.

Swem, E.G. Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis of Williamsburg, Virginia 1734-1746. Barre: Barre Gazette, 1957.