On a recent Friday, under a leaden and turbulent sky, our drone made a final pass over the excavation site of the First Baptist Church on Nassau Street, capturing closing images of the archaeological fieldwork. Two and a half years earlier, on a hot September Sunday, First Baptist’s descendants launched the excavation with a prayer vigil. Prayers were offered for the project’s success: that Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeological team would find, beneath an asphalt parking lot, the physical remains of one of the earliest churches in the country established by, and for, an enslaved and free Black congregation. At the risk of spoiling the conclusion, it was an auspicious beginning.

Planned to last one year, the excavation phase of this project was extended several times for all the best reasons. The site was richer than anticipated and presented unexpected discoveries. More significant, a sustained archaeological presence on Nassau Street provoked unusually thoughtful conversations between archaeologists, community descendants, and museum guests. It will be difficult to leave what feels like a perfect situation. But with 92% of the original church site now excavated, we recognize that we have answered the questions that can be answered by digging. Now, as we move into the lab for the project’s next phase, it’s time to summarize what we’ve learned so far.

It is to the credit of the descendant community that the story of the Historic First Baptist Church is increasingly familiar. Worshipping today in a church on Scotland Street, the First Baptist Church congregation traces its roots to open air worship on the outskirts of Williamsburg in 1776. By the early 19th century, preacher Gowan Pamphlet led his congregation to Nassau Street, where they gathered on a sliver of land provided by businessman Jesse Cole. When a tornado destroyed their place of worship in 1834, they rebuilt, this time in brick. And when Colonial Williamsburg’s expansion drove the congregation from its Nassau Street home in the late 1950s, First Baptist Church built a new church several blocks away. Nevertheless, ties to the original site run deep.

The archaeological goal of this project has been to find the early 19th century structure where that congregation got its start, and to explore the surrounding landscape in enough detail to allow accurate physical reconstruction. Of course, the recovery of artifacts was also a focus, for the insights they offer into the lived experience of early worshippers.

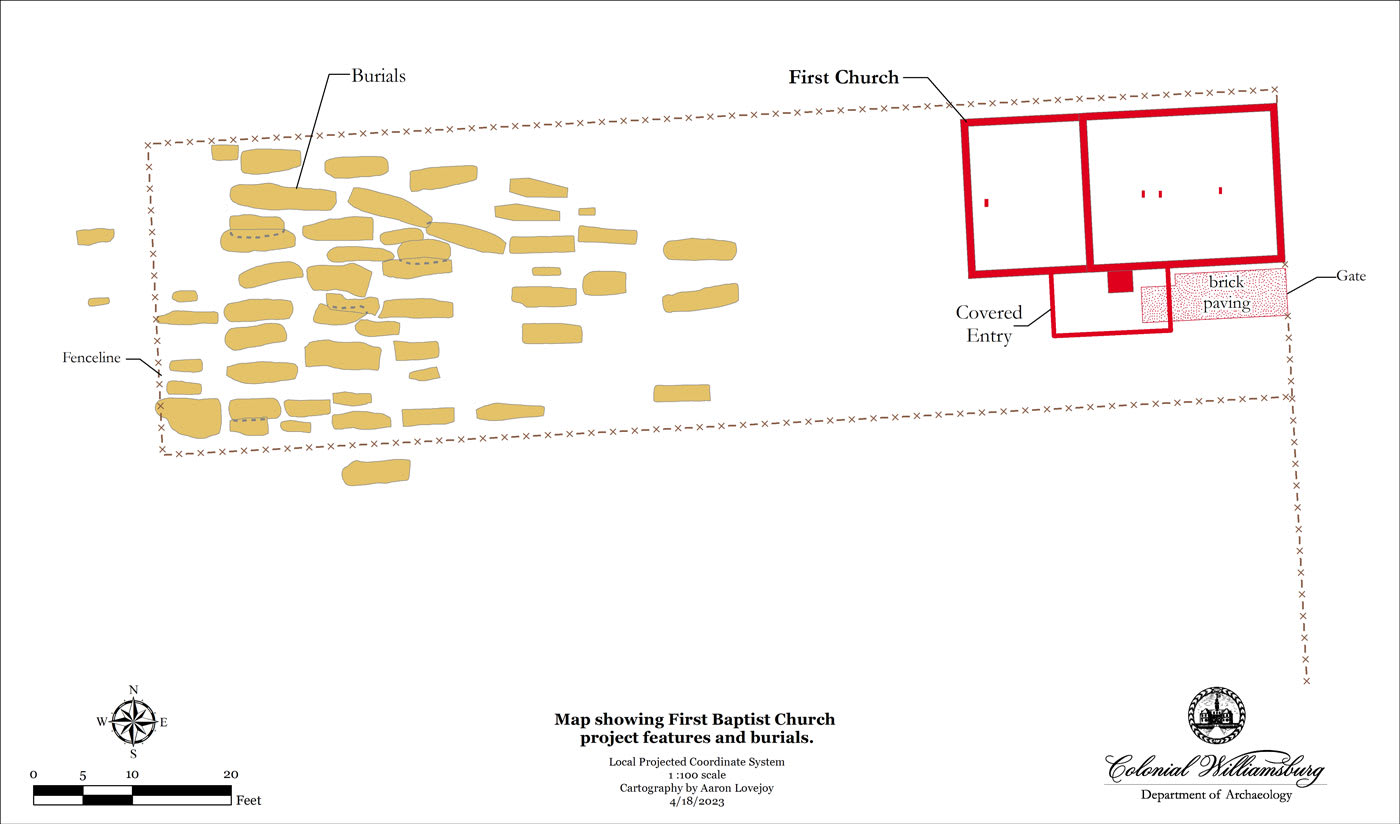

Two years of digging have revealed that the first church was a simple frame structure, resting on a brick foundation. Built around 1805, it was expanded a little more than a decade later. Excavation has yielded some edits to the slim oral history of this building. Once thought to have been given, along with the land, by Jesse Cole, archaeological evidence now suggests that the congregation built its own church.

Worshippers entered the building through a door centered on the long south side. A surviving brick step indicated this door’s location, and a halo scatter of 160 straight pins, swept from the worship space into the surrounding yard, confirmed it. There were steady improvements to the property. Congregants gathering on a hot or rainy Sunday would appreciate the 6’ x 12’ shelter around the door, which extended the worship space and offered protection from the elements. Sometime around 1820, a brick walkway was laid along the south side of the building, leading congregants from Nassau Street to the entrance.

We have learned that the church had a wooden floor. Four bricks running down the center of the foundation at regular intervals once supported floor joists and kept the floor from sagging. Gouges on the surfaces of two of those brick supports reveal the placement of shims to tighten the support.

The surrounding landscape almost certainly posed challenges to early 19th century builders. Relatively flat today, the First Baptist Church lot is intruded by the head of a ravine, still visible on the opposite side of Nassau Street. That ravine began to silt in around 1720, according to the work of geoarchaeologist Howard Cyr, and sometime after 1750 it was choked by sediment from a catastrophic weather event. By the time the congregation received the property early in the 19th century, it was gently sloped, but low-lying, seasonally wet, and unstable.

What did this mean for the members of the church? Worshippers needed to choose their footing carefully as they maneuvered from the street to the church door. More than an embellishment, the brick paving that approached the south entrance was needed to protect Sunday attire. Swampy terrain presented even greater consequences for the building’s caretakers. Built directly on unstable sediments, the church’s south foundation wall tipped visibly toward the ravine, compromising construction.

The discovery of graves on the First Baptist Church site refocused our second years’ work from the church building to its members. Sometime in the first half of the 19th century members of this congregation began to bury their dead on the property. Sixty-three burials have been recorded, identified by their rectangular shape and the deep orange clay they contain. These stains mark the shaft in which a coffin or body was laid.

Even without digging certain observations can be made about this cemetery. All graves are oriented east-west, a practice common to many religious traditions. Individuals were buried in rows, although crowding eventually caused those rows to overlap, making the cemetery appear less orderly. Adults and children were buried here, based on dimensions of the graves; about 20% of those buried were infants or young children. The burials do not appear to be marked or were marked with something impermanent.

Descendants of the First Baptist Church community, our generous and enthusiastic collaborators on this project, have guided all decisions concerning the graves. Lying within the protected Historic Area, the graves need not be disturbed at all. Descendants were consulted about how to proceed: whether to abandon excavation in the burial ground, to uncover the grave stains and commemorate in place, or to excavate some of the burials to evaluate their potential for scientific analysis. At a meeting on May 10, 2022, the community voted for the third option. Three burials were selected for excavation to assess the condition of the remains; to date the burials to assure their association with the church; and to determine whether the interred were of African descent.

That work was conducted in July and August of 2022. The archaeological results were the first to come in. All three individuals were found to be buried in hexagonal (shouldered) coffins. Although the wood was long-decayed, the positions of nails, and an organic stain marked the coffins’ former locations. The nails dated the coffins to the first half of the 19th century. One of the coffins appears to have been moved, long after initial burial.

Two of the interred were buried in clothing identified, in one case, by the presence of four (copper alloy) vest buttons and three trouser buttons, and in the second case by a single bone button. Buttons and the clothing styles confirmed an early 19th century burial. The third individual appears to have been wrapped in a shroud secured by a single pin.

Although preservation varied between burials, their condition was generally poorer than we had hoped. This posed challenges for the project’s next steps, which included extracting a DNA sample, and lifting the remains for osteological analysis. Here the archaeological team leaned on the expertise of three specialists: Dr. Raquel Fleskes, an ancient DNA analyst at the University of Connecticut, and Drs. Michael Blakey and Joseph Jones, who conduct osteological analysis at William & Mary’s Institute for Historical Biology (IHB).

The archaeological team successfully recovered DNA samples from all three burials. Extracted most reliably from the petrous, a bony structure behind the ear, these samples were delivered in early September to Dr. Fleskes at the University of Connecticut’s Ancient DNA Lab. The remaining bones, where preservation allowed, were carefully lifted, and transported to the IHB for analysis.

For months we have waited — sometimes patiently, sometimes not — for the results. And those results were returned in early April. At a recent celebratory gathering at the city’s Stryker Building, descendants and invited guests learned from Drs. Fleskes, Blakey, and Jones what their analysis revealed about the burials. All three, we now know, are male. Two were older individuals (defined as 35-45), while the third was between the ages of 16 and 18. They ranged in height from 5’4” to 5’8”. Work stress left marks on some of the long bones, and tooth enamel recorded nutritional stressors. The most highly anticipated results were delivered by Dr. Fleskes, who confirmed sub-Saharan African descent for the only individual whose DNA survived the enrichment process. “These people are ours,” was the response from descendants.

Work doesn’t stop here. In the months ahead, archaeological focus will shift to different tasks including analysis of what will likely amount to more than 200,000 artifacts, and continued conversation with the descendant community as we work to interpret the evidence. And the excavated human remains will be returned to their graves.

With so many tasks to address, it is important to acknowledge this project’s intangible results. Over the last two years, excavation on the site of the First Baptist Church has opened a space for conversation. Those casual interactions have connected archaeologists and members of the descendant community, archaeologists and Colonial Williamsburg visitors, William & Mary visitors and descendants all across the Greater Williamsburg area. Speaking only for myself, I have learned from each conversation. I see things differently than I did two years ago. I don’t think I’m alone.

Descendants have brought grandchildren to the site to participate in uncovering church history, and Open House events have invited visitors behind the ropes. College classes and museum professionals have toured the site. Not every interaction has been easy, but we continue to talk. Archaeology is slow by nature, and sometimes that works in our favor. We have time.

Meredith Poole has been a Staff Archaeologists at Colonial Williamsburg for 37 years. Her career started with the 1985 excavation at Shields Tavern and has continued through more recent projects at Charlton’s Coffeehouse, the Public Armoury, and the Market House. Meredith has shared her enthusiasm for archaeology in a variety of forms: managing the Reconstruction Blog, leading archaeological walking tours along Duke of Gloucester Street, and overseeing the Kids Dig on Duke of Gloucester Street. She lives in Williamsburg with her husband, Joe. They have two adult children.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.