Since July 2021, the archaeological crew has been diligently making new discoveries at the Powder Magazine (Fig. 1). This is the first time we’ve excavated around the base of the Magazine since the foundation of the brick wall around the building was uncovered in the 1930s, making this a very exciting opportunity for the Archaeological Department!

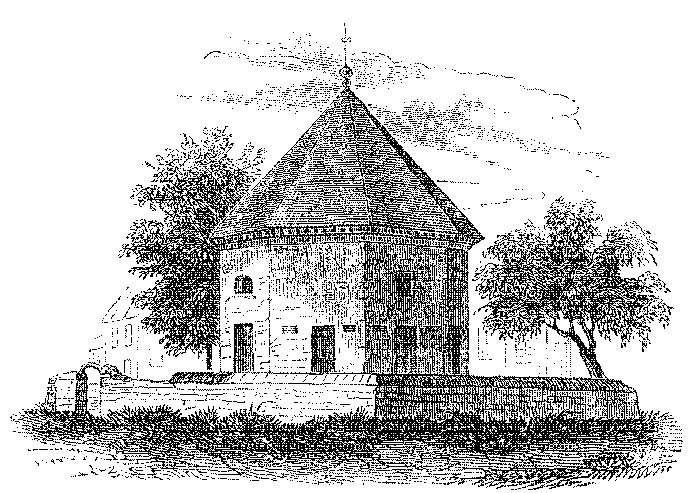

The Powder Magazine, one of the 89 surviving 18th-century structures in Colonial Williamsburg’s historic area, has been a noteworthy Williamsburg landmark since it was built. Its long history and unique octagonal design have captured the attention of visitors and preservationists since the 19th century. The Powder Magazine was commissioned by Governor Spotswood in 1714 as a storehouse for military supplies and equipment. Everything that a soldier would need, from ammunition and guns to mess kits and tents, were stored in the three-story structure.

While initially constructed as a Magazine, the building served a variety of uses through the decades, resulting in significant modifications to the structure. The French and Indian War brought about the heaviest use of the Magazine, prompting the construction of the surrounding brick wall in 1755 (Fig. 2). The most famous historical event to take place at the Powder Magazine was the Gunpowder Incident of 1775, one of the inciting incidents of the American Revolution, when the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, fearing revolt, seized the gunpowder stores from the public powder magazine. After the Revolutionary War, the building ceased to be used as a Magazine and was sold to a private owner. Throughout the 19th century, the building was used as an extension of the market house, a Baptist meeting house, a livery stable, and finally a museum.

After suffering from years of neglect, the eastern and northeastern walls of the Powder Magazine collapsed in early 1888 (Fig. 3). That same year, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia (APVA), known today as Preservation Virginia, began negotiations to purchase and restore the building. While negotiations were underway, the roof caught fire, leaving an unstable and partially ruined structure. In the years that followed, APVA rebuilt significant portions of the Magazine’s brick walls and it was eventually opened to the public. Today, the Magazine has functioned as a museum longer than it was ever used as a military warehouse.

In preparation for the 250th anniversary of the Gunpowder Incident, a project was undertaken in the summer of 2021 to restore the Magazine to its 18th-century appearance. While the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Architectural Preservation has been hard at work closely examining the building for clues, our team has pitched in to look for evidence buried under the ground (Fig 4). As is the case with all archaeological investigations, the first stages of excavation often lead to more questions than answers, but we will learn much more as we move int the next phase and begin analyzing the artifacts we’ve collected. Even in these early stages, though, we’ve already uncovered some very cool information about the Magazine!

Among the most exciting finds have been dozens of pieces of that we’ve found scattered around the site. If you walk up to the Magazine today, you will see the wooden shingles that were placed on the building during the 1930s reconstruction. However, based on these new finds, we believe that the Magazine would have had a clay-tiled roof when it was first constructed. This would likely have been to improve flame resistance—which makes sense considering that gunpowder was once stored here. Considering the higher quality of the roofing tiles found at the Magazine compared to others found around Williamsburg, it’s possible that they were imported from Europe rather than being made in a local kiln.

A lot of the clay roofing tiles have been found dumped into holes left by the removal of large wooden posts (Fig. 5). We’ve found several of these posts approximately 10 feet from the Magazine building. Our question moving into the next couple of months is “will the pattern of posts continue all the way around the building or only in certain sections?” Due to the size of these posts, we believe they were used to support a structure instead of a fence or stockade line. Additionally, we recently uncovered a section of the original 18th-century brick wall surrounding the Magazine. Interestingly, the original wall section that was never removed when the current wall was rebuilt in the 1940s. Instead, it was incorporated into its construction. This discovery has been beneficial for our architectural historians whose goals is to better understand the appearance and height of the original 18th-century wall—which may have been a bit shorter than the reconstructed wall.

Along with the many archaeological features we’ve found surrounding the Powder Magazine, we’ve recovered thousands of artifacts that provide evidence of the military activity that took place at the site as well as the history of the building’s many uses. Colonial military artifacts have included English and French gun flints, a spring that was once part of a flintlock mechanism, musket balls, and two cannonballs. We’ve have also found evidence of Civil War soldiers at the Magazine, several unfired Minié balls and pistol shot from Civil War-era weapons have been recovered as well. A common question the team gets asked is if we’ve found any gold. While we haven’t found any so far (and we rarely do), we have found two Virginia half pennies that date to 1773.

We have a great deal more work ahead of us over the next several months as we continue excavating around the Powder Magazine. The more we uncover, the more we will understand about the 18th-century appearance of the building and how the colonial people of Williamsburg used the Magazine and surrounding courtyard. If you’re planning a visit to Colonial Williamsburg this spring, make sure to stop by the Magazine and check out the new things we’re finding!

Jessie Dick is a Project Archaeologist with the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeology, primarily overseeing the excavations for the Magazine Courtyard project and a variety of smaller projects throughout the historic district. She first got her start with the department working for a summer with the Kids Dig program. When she is not out digging, she spends time with her husband and two dogs, most likely somewhere inside.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.