Although today we typically think of buttons as purely utilitarian objects, they can also be quite decorative, and their appearance can drastically change the overall aesthetic and interpretation of a garment. One officer’s coat in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation collection has had numerous button makeovers throughout its lifetime. This summer, as an intern in the Textile Conservation Lab, I have worked to restore the buttons to what is believed to be their original appearance.

The coat, which dates to ca. 1770, is said to have belonged to Amos King of Massachusetts, a major in the “fifth Regiment of Infantry, in the first Brigade and second Division of the Militia.” It is made of wool that is dyed bright red using cochineal, a pigment derived from the body of the cochineal insect. Along the front of the coat was a row of ten round gilt buttons. While at first glance, these did not appear out of place, the maker’s mark on the back of each button suggests otherwise. It reads “H. Sandland/Superfine” and this information can be used to help date the buttons to the mid 19th century. Fiber analysis of the thread used to the secure the buttons to the coat, further suggests that they are a later addition to the garment.

So what buttons were originally on the coat? Luckily, a likely answer can be found on the back of the garment.

Located on the back pleats of the coat are four thread-wrapped buttons. These buttons are wrapped in a wool/silk blend thread of a darker color than the wool of the coat in a “death head” pattern.

Death head buttons were a common type of thread-wrapped or passementerie button used in the 17th and 18th centuries. The style is characterized by a central X that forms at the junction of the wrapping thread. This X, which is reminiscent of the crossed bones in a skull and crossbones, could be the source of the button’s name. They typically have a wood or bone mold and are wrapped with wool or wool-silk thread. The most common style of death head button was a four-segmented X like that seen on the officer’s coat. However, more complex designs, such as six segments, came in style at the beginning of the 18th century. Death head buttons were commonly found on middle- and upper-class men’s clothing, particularly jackets or waistcoats.

It is believed that the buttons on the front of this coat would have also been death head buttons, so the decision was made to create reproductions. Historically, death head buttons were made in England and the American colonies in both factories and cottage industry. In England, this industry centered in Dorset, where many Huguenot lace-workers had migrated. In general, the thread-wrapping process was considered appropriate work for women and children, and so I joined their ranks! After much trial and error, I mastered the thread-wrapping process — thank heavens for YouTube!

As noted, the color of the original death head buttons on the back is darker than the wool of the coat. This could suggest discoloration of the original material or that the buttons were purchased premade and not dyed to match, which was a common practice. Nevertheless, it was decided that the reproductions should match the style of the original buttons while matching the color of the coat itself. Additionally, the reproduction buttons were made with modern materials that matched the appearance of the originals but made them clearly discernable by future scholars.

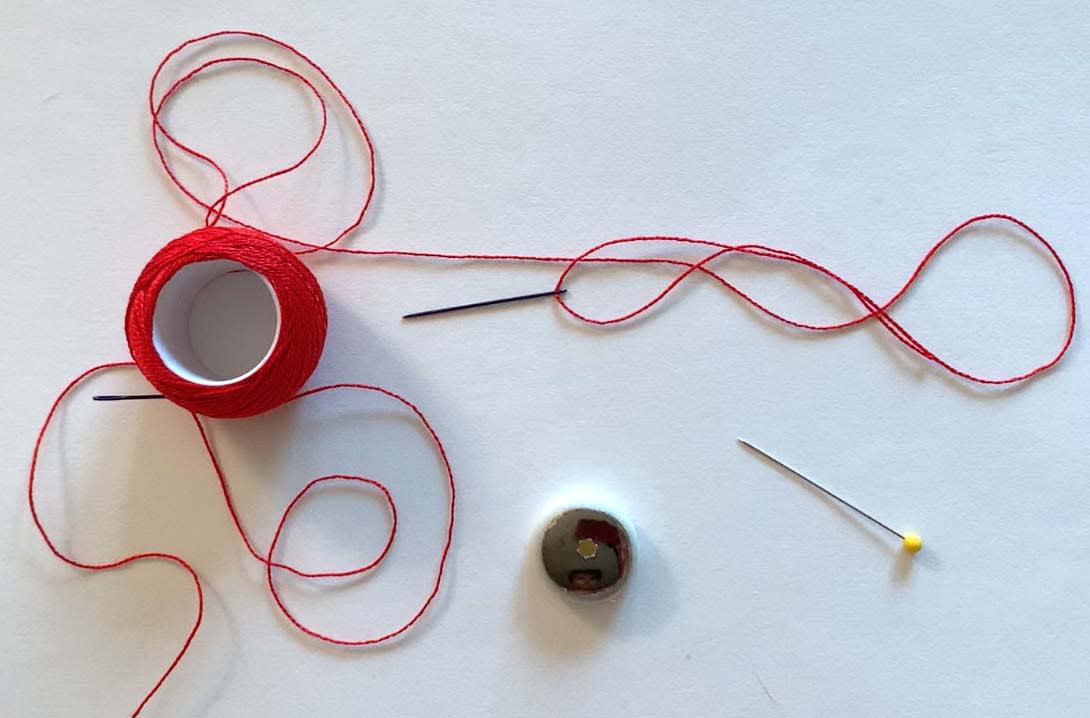

To create the underlying mold for the buttons, I modified store bought plastic buttons. This included sawing off the shank, drilling a hole in the middle, and sanding them to more closely match the domed shape of the originals. Once the molds were prepared, I wrapped them using the traditional death head pattern. Although the originals are wrapped in a wool, silk blend, the reproductions are wrapped in a pearl cotton. This has less risk of attracting pests which are drawn to proteinaceous fibers like wool, and the pearl cotton was available in the appropriate sheen and color.

Once all ten of the buttons were ready, I removed (but saved!) the gilt buttons and sewed the new buttons in place.

This intervention may seem extreme. The gilt buttons did not pose a risk to the preservation of the coat. However, all of my work has been fully documented with written and photographic records that will join the object’s carefully compiled records, and with the new death head buttons in place, the coat more closely resembles its original appearance and can thus be more accurately interpreted. To see the coat with its new buttons in person, visit it at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, where it will be on display beginning in the Fall of 2020.

Annabelle Camp is a second-year National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, where she majors in Textile Conservation with a minor Organic Objects Conservation. Camp interned in the Textile Conservation Lab this summer.

Resources

Fuss, Norman. 2005. Death Head Buttons: Their Use and Construction.

Hughes, Elizabeth. 2006. The Big Book of Buttons. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital, plus, explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers to plan your visit.