Williamsburg was one of the centers of ornamental gardening in colonial America. On land long cultivated by Indigenous peoples, often using the labor of enslaved people of African descent, Williamsburg’s settlers created some of the continent’s finest European-style eighteenth-century gardens. Colonial Williamsburg has researched and reconstructed many of these gardens. Most of them are freely open to the public.

American Indian planting

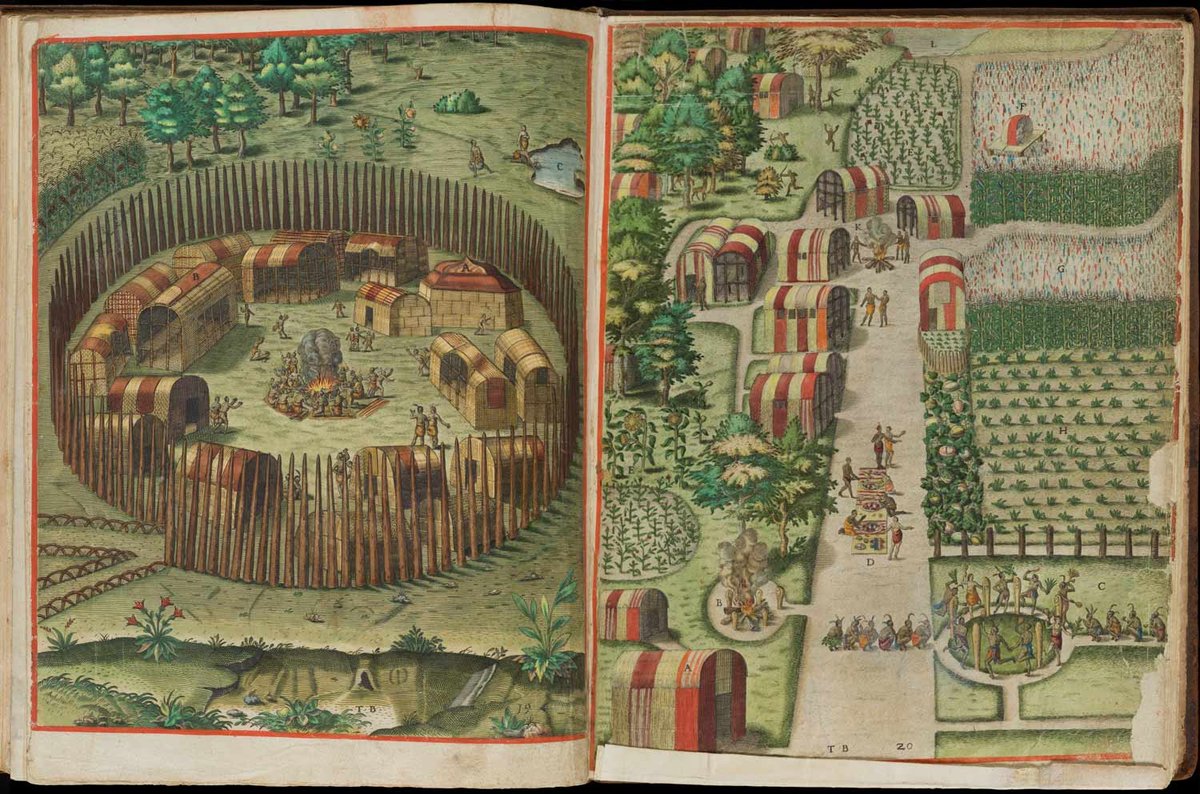

Algonquian-speaking Native people gardened, farmed, and harvested plants in the Chesapeake region long before European colonizers arrived at Jamestown. Archaeological excavations indicate that Indigenous groups in what is now eastern Virginia frequently cultivated small garden plots alongside their homes, as well as larger farms. The Chickahominy people gardened in floodplain terrace plots along low-lying river lands. They grew corn, beans, and squash (the nutritious and mutually supportive trio often known as the “Three Sisters”) as well as gourds, tobacco, sunflowers, and more.1 Native women and girls across the region also harvested edible wild plants, sometimes traveling great distances to find plants ripe for harvest. 2

When English colonists invaded Virginia, they took note of Native agricultural and gardening practices. Englishman Thomas Harriot’s account of sixteenth-century Virginia describes a town called Secota that had cornfields and gardens shaped like the letter E, where they “groweth Tobacco which the inhabitants call Vppowoc.”3 As greater numbers of English colonists arrived, their free-roaming livestock often destroyed these gardens, causing conflict with Native people.4

Planting Williamsburg

English colonization likely made Virginia uglier. When the first Englishmen arrived in Virginia, they described it as a garden paradise, a land “all flowing over with fair flowers of sundry colors and kinds, as though it had been any garden or orchard in England.”5 But over time, colonists destroyed many of these diverse, complex ecosystems and replaced them with a dull landscape of denuded forests, fenced pastures, and endless tobacco fields.6

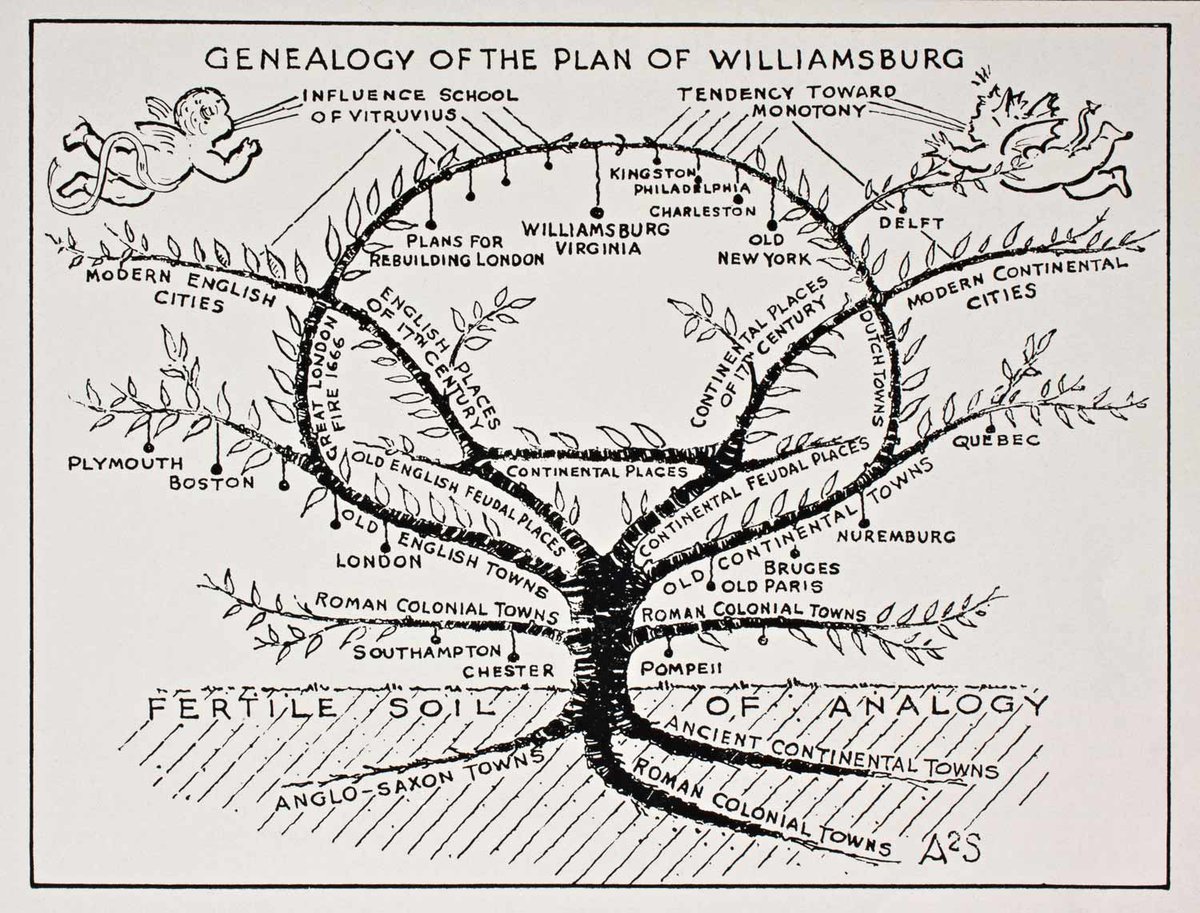

In 1699, the Virginia General Assembly directed the construction of Williamsburg as the colony’s new capital city. It was laid out in spacious half-acre lots, which one observer noted were “sufficient each for a House and Garden.”7 The result was a more sparsely settled, greener town than northern capitals like Boston and Philadelphia.8 A 1705 law requiring landowners to enclose their lots also ensured that there would always be a fence or wall between Williamsburg’s gardens and curious local animals.9 The city became known for its beautiful gardens. 10

The symmetrical, enclosed style of Williamsburg’s early gardens emphasized control of nature. This kind of garden was popular in England in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. There is little evidence to suggest that Virginians widely adopted the more naturalistic landscape design that became fashionable in England in the mid-eighteenth century. Never far from wild landscapes, the colonists apparently did not feel the need to recreate them in their gardens.11

Enslaved gardeners

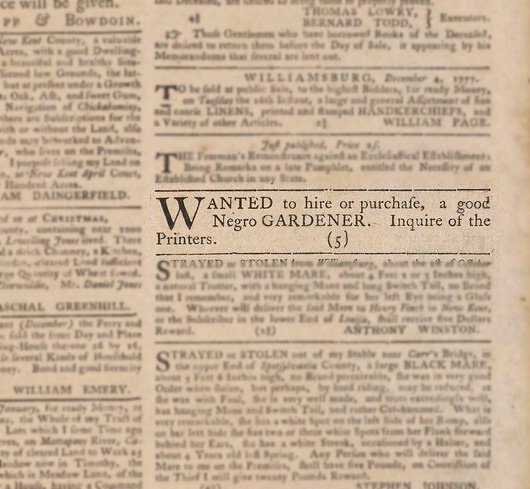

Decorative gardens were rare in seventeenth-century Virginia, partly because it took so much labor to plant, water, and tend to them. But as white colonists enslaved growing numbers of people of African descent during the eighteenth century, their gardening ambitions grew. The surplus of labor provided by racial slavery made it practical for Virginia elites to engage in large-scale decorative gardening projects.12 As they built and maintained these gardens, enslaved people developed expertise that was highly valued by their enslavers.

Go Deeper: What do we know about Williamsburg’s enslaved gardeners?

1694–1720: Building Williamsburg’s Public Gardens

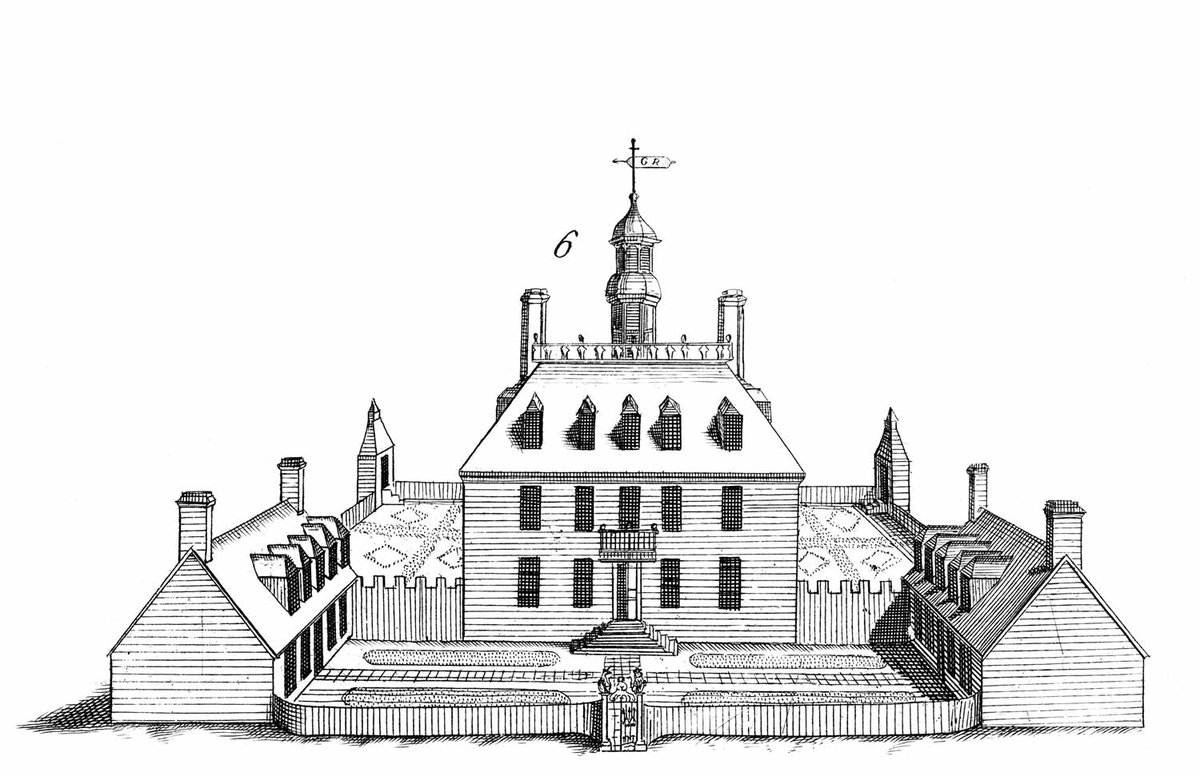

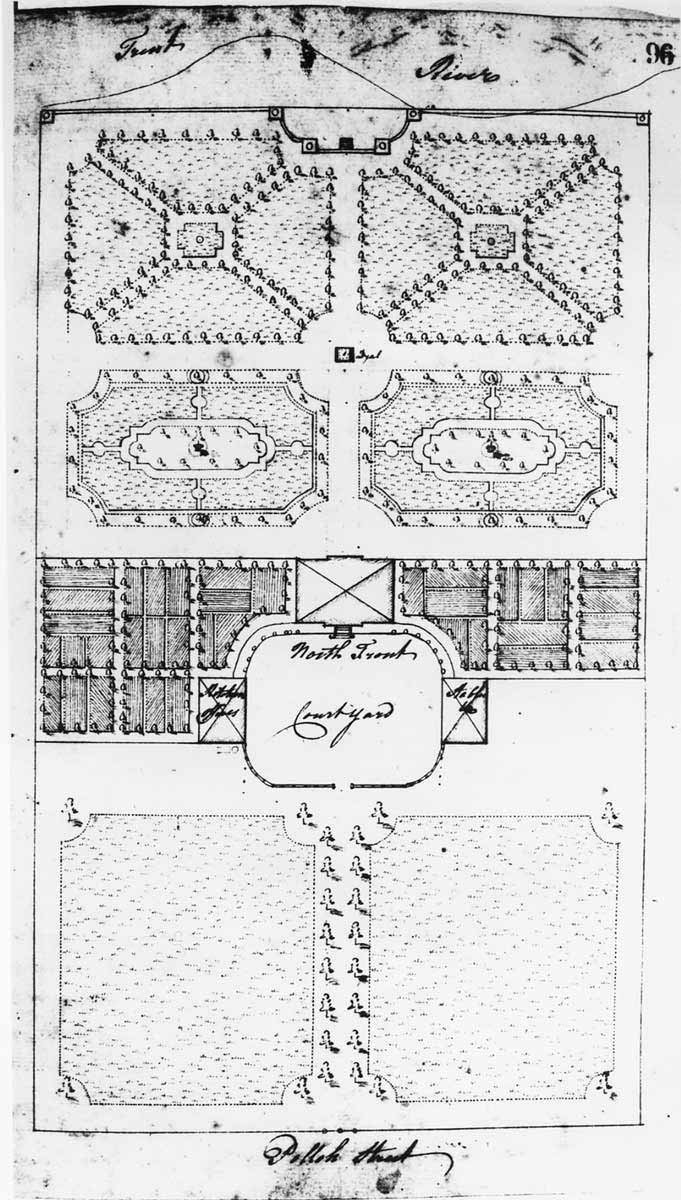

The first large ornamental garden in what became Williamsburg was planted on the grounds of the College of William & Mary. Designed by an assistant to the King’s gardener, the College gardens were orderly, symmetrical, and formal.13 To the east of the main building were small evergreen topiaries carved from bushes and trees. On the west side, a kitchen garden grew alongside a covered porch and courtyard (which may have been used for commencement and other events). There were apparently no flowers to distract the scholars.14

Go Deeper: Read about archaeological findings at the William & Mary gardens.

The Governor’s Palace was the site of the second great public garden in Williamsburg. Designed largely by Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, the elegant Palace gardens featured decorative gates, geometric flower designs, sunken fences, a canal, fish ponds, terraces, and an earthen mount covering an ice house. They were perhaps the most impressive gardens in the British colonies in the early eighteenth century. Indeed, they were so elaborate that their cost helped to alienate Spotswood from the Virginia gentry, contributing to his being recalled as Lieutenant Governor.15

Go Deeper: The Palace Gardens were among the finest in the American colonies.

Enslaved Peoples’ Plantation Gardens

On nights and Sundays, the only free time available to them, enslaved people tended their own garden plots on Virginia plantations. They fed themselves with high-yield crops like potatoes, beans, peas, collards, and melons. Some enslaved people also sold their produce.

Go Deeper: How did enslaved people use their garden plots to seek freedom?

1717–1749: Custis Garden

Many eighteenth-century plantation owners used the profits generated by the labor of enslaved people to create fashionable mansions and elegant, formal gardens.16 The most prominent gentry gardener in Williamsburg was John Custis IV. For decades, he managed a large garden on his four-acre property at the corner of Francis and Nassau Streets. Custis took pride in his garden, which he rated “inferior to few, if any, in Virg[ini]a.”17 But while Custis occasionally got his hands dirty, enslaved people did most of the work to maintain this garden. Custis enslaved at least two hundred people across his plantations, and his Williamsburg garden displayed the skill and expertise of the enslaved horticulturalists who planted, weeded, and watered it.18

Colonial Williamsburg recently completed a five-year archaeological investigation into the four-acre Custis Square site, which will result in the restoration of this important eighteenth-century garden.

Go Deeper: What did the Custis garden look like?

1760s: The First American Garden Book

Another of Williamsburg’s notable gentry gardeners was John Randolph. Randolph was a lawyer, Loyalist, and an avid gardener. He wrote what is widely considered to be the first American vegetable gardening book, A Treatise on Gardening, sometime in the 1760s.19 It was an update of Philip Miller’s popular English The Gardener’s Dictionary for American audiences.20

Go Deeper: Read Randolph’s A Treatise on Gardening.

Middling Gardens

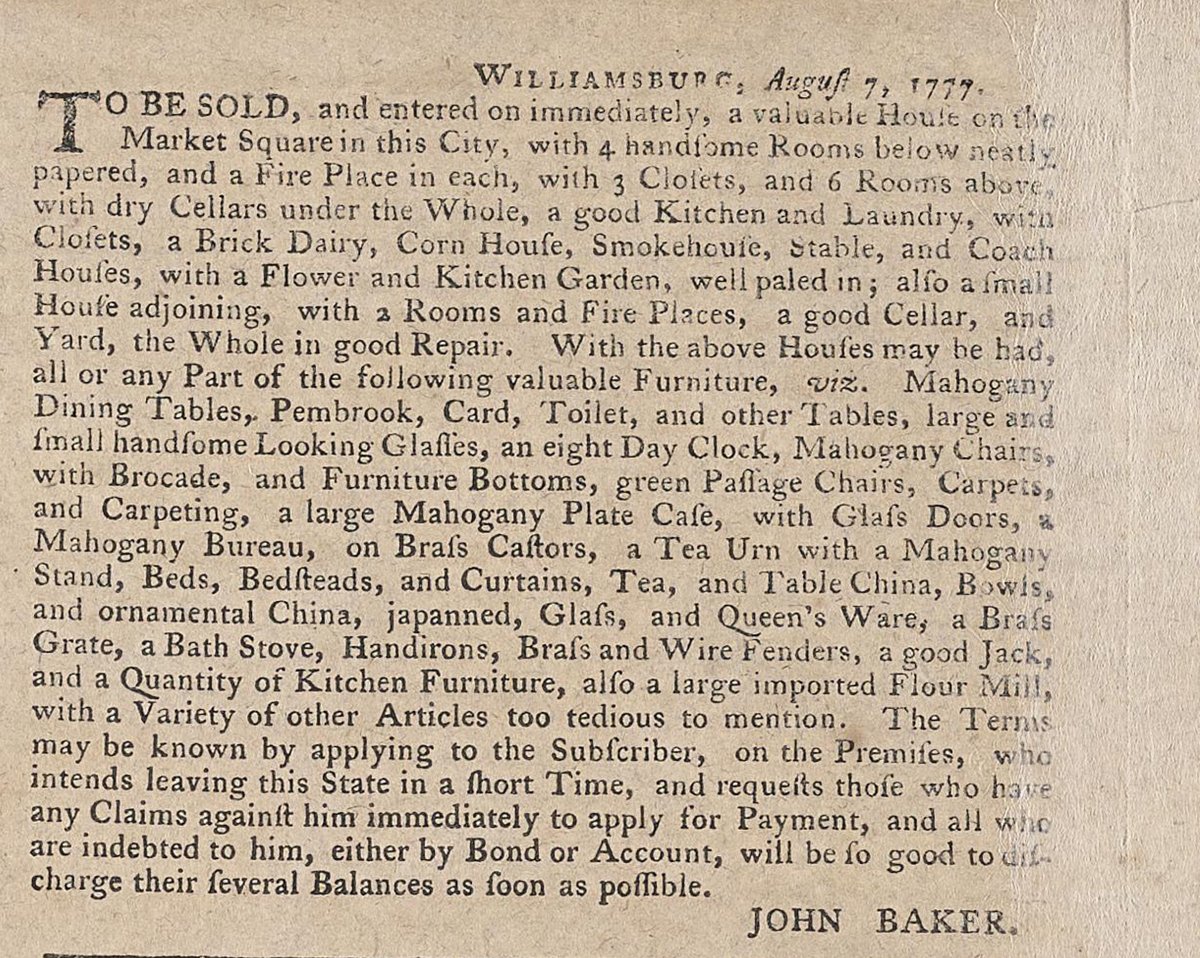

How many people had gardens in Williamsburg? According to estate inventories, which record the possessions of deceased people, wealthy families were more likely to own garden tools. These tools were not as common in the inventories of less prosperous households. Only about a fifth of advertisements in the Virginia Gazette selling property (across the colony) mention a garden. It is likely that ornamental gardens adorned the homes of plantation owners, doctors, lawyers, merchants, tavern owners, and prosperous tradesmen, but there is less evidence that gardens were present in the homes of the lower classes. 21

Many middling households and taverns kept “kitchen” gardens, which grew foods and herbs rather than ornamental plants.27 But many households would have found it challenging to manage a kitchen garden. Vegetable gardens required more water than, for example, an ornamental hedge or a flower garden. The difficulty of obtaining and transporting water likely prevented many households from attempting to garden at all.

1930s–Now: Restoration of Williamsburg’s Gardens

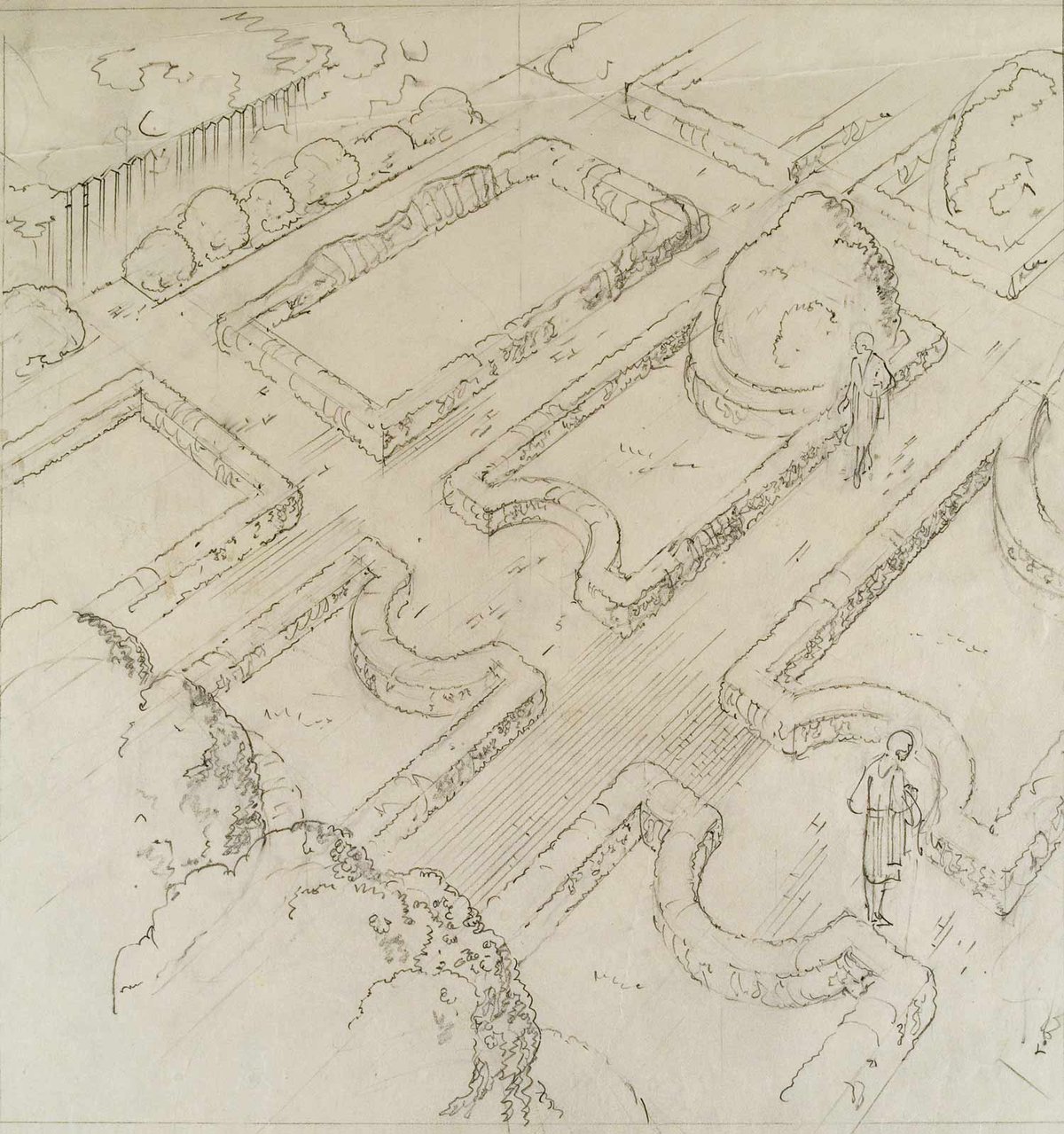

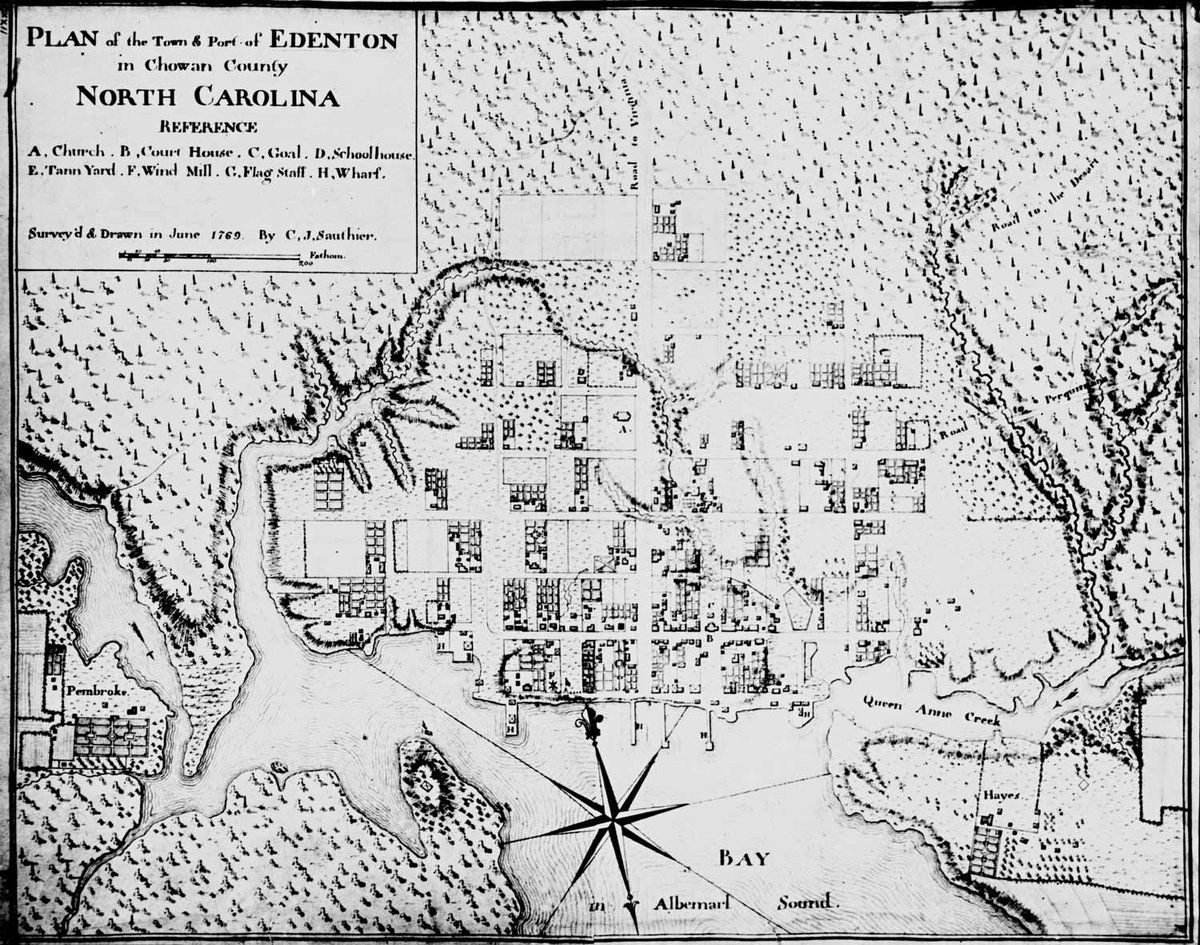

In the 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg began to restore eighteenth-century Williamsburg. While some original buildings remained, the city’s landscape had transformed considerably over the years. The renowned landscape designer Arthur A. Shurcliff relied on several sources to understand what these gardens would have looked like. First, initial archaeological excavations identified garden walkways, outbuilding foundations, and fence lines. This helped to determine the original layouts of some gardens. Second, researchers used contemporary maps, especially the so-called “Frenchman’s map” to identify fences, trees, and other features. Third, they relied on the drawings of Claude Joseph Sauthier, a French surveyor who mapped several North Carolina towns and their gardens in 1767, to understand the style and pattern of gardens in the southern colonies.28

Lacking detailed evidence for many garden sites, some of the details in Shurcliff’s designs were conjectural. In later years, Shurcliff’s designs have been criticized for presenting an idealized vision of the past. Would Williamsburg have been so well-manicured in the eighteenth century? Was Shurcliff influenced by the “colonial revival” landscape architecture movement that was popular in the early twentieth century? Emerging research continues to guide updated landscape designs on numerous sites in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Since the 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg has maintained support gardens and nurseries to supply the Historic Area and other properties with plants and decorations. The first nursery and greenhouse dates to 1948. In 2019, a tree nursery was established to support the Arboretum. That same year, a new compost and mulching operation was developed at the nursery to recycle leaves and plant debris. A new greenhouse will open in 2025.

Today

One of the major challenges facing Colonial Williamsburg’s gardens in the twenty-first century is the emergence of boxwood blight. A hardy evergreen shrub, boxwood is a fixture of many of Colonial Williamsburg’s gardens. Some boxwood plants in the Historic Area date from the 1830s. In 2021, the contagious fungal infection boxwood blight spread to several Colonial Williamsburg gardens.

The Landscape Services team has been working to prevent its spread. As challenging as boxwood blight will be in the coming years, it also presents “an opportunity to true-up to gardens,” said Landscape Manager Melissa Sharifi, “Would this many boxwood have really been here in the eighteenth century? It’s unlikely.” Over time, some blighted boxwood will be replaced with a variety of plants, to create more historically accurate biodiversity in the gardens.

Further Reading

- M. Kent Brinkley and Gordon W. Chappell, The Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1996).

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001).

- E. G. Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia. 1734–1746 (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1957).

- Josephine Little Zuppan, ed., The Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717–1742 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

Sources

- Martin D. Gallivan, The Powhatan Landscape: An Archaeological History of the Algonquian Chesapeake (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016), 30, 110, 144; Stephen R. Potter, Commoners, Tribute, and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993 ), 29, 34, 102, 225.

- Helen C. Rountree and E. Randolph Turner III, Before and After Jamestown: Virginia’s Powhatans and Their Predecessors (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002), 92–98.

- Thomas Harriot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (New York: Dover Publications, 1972; 1590), 68. Link.

- Potter, Commoners, Tribute, and Chiefs, 196.

- Observations Gathered Out of ‘A Discourse of the Plantation of the Southerne Colonie in Virginia by the English,’ 1606. Written by that honorable gentleman, Master George Percy, ed. David B. Quinn (Charlottesville: Association for the Preservation of Virginia Anitquities, 1967), 17.

- James D. Rice, Nature & History in the Potomac Country: From Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 117.

- Hugh Jones, The present state of Virginia (New York: J. Sabin, 1724), 32.

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 81.

- William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, vol. 3 (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 430, link. Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, 81.

- Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, ch. 2–4.

- M. Kent Brinkley and Gordon W. Chappell, The Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1996), 1. Scholar Peter Martin has emphasized that “touches” of naturalistic, picturesque landscape design emerged in Virginia gardens over the course of the eighteenth century, without displacing the formal, geometric designs of earlier gardens. Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, xxii.

- Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, 7, 14.

- In 1694, the London garden designer John Evelyn wrote to a Virginian explaining that “his Majs Gardner here” had sent “an ingenious Servant of his” to Virginia to “make and plant the Garden, designed for the new Colledge, newly built in your Country.” Quoted in Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, 19.

- Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, 19–25, 40–41.

- Martin, Pleasure Gardens of Virginia, 43–50; Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 4.

- Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), ch. 4.

- E. G. Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia. 1734–1746 (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1957), 23–24, link; Patricia Samford, “Custis Garden Archaeological Report, Block 4,” 1987, Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, link

- Josephine Little Zuppan, ed., The Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717–1742 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), 10.

- A Treatise on Gardening: By a Citizen of Virginia John Randolph, Jr., ed. M. F. Warner (Richmond: Appeals Press, 1924), x. Link. It was first published in the United States in 1788.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 7.

- Don McKelvey, “Garden Study,” (report for Colonial Williamsburg Department of Landscape Services, 2013).

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 64–68.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 136–37.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 142–44.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 114–118.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 128–132.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 3–4.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 2–3.