xxxxx

The Tea Crisis

When we think about British America’s Tea Crisis of 1773, we usually think of Boston. On the evening of December 16, 1773, the town’s residents famously dumped 340 chests of East India Company (EIC) tea into the harbor. The way that most Americans encounter this story, the Tea Act affected all the colonies, but Boston reacted on everyone’s behalf. It’s the story of the Boston Tea Party.

Historians now know that this narrative is much too narrow. In fact, the Tea Crisis unfolded slowly across Britain’s Atlantic colonies. Parliament’s efforts to enforce trade laws and taxes on tea imported into the colonies placed them in conflict with colonists across North America. Rejecting Parliament’s authority to tax them, the colonists protested, sometimes violently.

What did the tea crisis look like from Williamsburg? How did Virginians react to news from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston as it arrived? How long did it take the news to travel, and how did that shape reactions in Virginia?

Readers of Williamsburg’s two newspapers, both called the Virginia Gazette, learned about the Tea Crisis slowly. As information trickled in, readers judged between conflicting and incomplete accounts. They didn’t know which ports would receive tea. They didn’t know whether British officials would successfully collect the taxes on the tea. They didn’t know whether any colonists would buy and drink it. And they didn’t know a world in which information could travel any faster than by horse or sailing ship.

Eventually, over the course of several months, they came to understand the scale and impact of the Tea Crisis. Reading the Virginia Gazettes week by week, as they would have done, we can begin to appreciate the uncertainty that American colonists must have felt about the future. In the sections below, we explore the crisis as it unfolded in the pages of the Virginia Gazette.

The Virginia Gazettes

Many Williamsburg residents learned about this crisis through the two Virginia Gazette newspapers. The older of the two publications had appeared for over twenty years by 1773, first from the printing office of William Hunter and later from the partners Alexander Purdie and John Dixon. The other Virginia Gazette first appeared in 1766 when printer William Rind arrived in Williamsburg after a lengthy career in Annapolis, Maryland. He had expanded his business to Williamsburg earlier, but relocated when he found the larger colony to be more lucrative.

During the colonial and revolutionary eras, newspaper printers largely tried to avoid explicit partisan affiliations. Their longstanding trade philosophy, championed by Benjamin Franklin, placed the newspaper at the service of the public rather than one political party. In practice, affiliations were common enough, especially in towns with multiple newspapers.

But the imperial controversy of the 1760s and 1770s forced printers to choose sides. Purdie and Dixon affiliated themselves closely with the revolutionaries. Clementina Rind, who had taken over for her husband William when he died in August 1773, likewise turned her Virginia Gazette toward politics. Though sometimes more balanced than Purdie and Dixon, she also supported the revolutionary movement. Over the lengthy tea crisis, there were sometimes significant contrasts in how the two Gazettes depicted events in New England.1

The Beginning of the Tea Crisis

Deep in debt and with tea wasting in its English warehouses, the East India Company (EIC) needed a bailout in 1773. The American colonists had long enjoyed smuggled tea, often from Dutch sources. If they could reduce this smuggling, leaders in London hoped they could save the EIC.

Rumors swirled about Parliament’s possible aid package. Would it include direct funding? A government loan? Favorable taxation rates? Would the EIC receive a monopoly on colonial markets? By late summer it was clear that the colonies would play a role in the EIC’s reinvigoration. On September 2, 1773, both papers published an identical report reprinted from Philadelphia, where it was originally published three weeks earlier:

With that first indication that tea would be shipped across the Atlantic, the race to cover and define the impact of the Tea Act was on.

November 25, 1773

By late November, the terms of the Tea Act were clear. Parliament reduced tax rates on imported tea. But they had also granted the EIC a monopoly on the sale of tea in the North American colonies.

Rejecting Parliament’s authority to tax them, revolutionary leaders cast the decision to drink EIC tea in stark

terms: to do so was to accept tyranny. It was clear that the EIC had sent tea to North America. But how much

tea? How many ships? Where would they arrive? These questions were subject to rumor and speculation.

Since tea would not arrive in any of their ports, Virginia colonists closely followed news from Charleston,

Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. The Virginia Gazettes shared news from those cities in their weekly issues,

published on Thursdays.

Reports from Boston typically appeared in Williamsburg newspapers two or three weeks after their first

appearance. Those from Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia took more than a week, and usually two, to arrive.

Virginia Gazette readers often found these delays frustrating. So much happened in a given week that

circumstances had changed by the time they were reported.

Both Gazettes of November 25, 1773, carried a report from Boston that a ship captain had refused to

carry the tea. He questioned “that the East India Company would send any Tea, fearing it would meet with a

Reception not at all to their Advantage in America.” This was a lonely reassurance, not borne out by the rest

of the reporting nor by future events. Boston reports from the first week of November included a call for a

town meeting to oppose the not-yet-landed tea, as well as a letter from “A Merchant” opposing the tea’s

landing.

Some remained open to the view that the Tea Act would benefit them. One local writer using the pseudonym “Landon Honduras” favored accepting the tea. Honduras

worried that even refusing to carry the tea would have dire consequences for colonists. According to Honduras,

the English might take American opposition as motivation to further enforce trade laws, and to do so using

English ships. American consent to the Tea Act, on the other hand, would allow American ships to become the

bearers of tea throughout the British empire, turning an imperial regulation into an opportunity for

additional revenue for the colonies. Landon Honduras thus adopted the logic behind the creation of the Tea

Act. Yet no one rose to his defense. Only a month later did anyone take the time to rebut his

arguments in the Virginia Gazette.

As Williamsburg residents were reading these reports during the last week of November, events in Boston and

Charleston took a dramatic turn. The first ships carrying tea arrived in their harbors. But Virginians would not

learn of these developments for weeks.

Click to Read more

December 2, 1773: News from London

By late November, the terms of the Tea Act were clear. Parliament reduced tax rates on imported tea. But they had also granted the EIC a monopoly on the sale of tea in the North American colonies.

In Virginia, Alexander Purdie, John Dixon, and Clementina Rind were still tracking late-summer reports from London about the East India Company and the tea. London news dominated the pages of colonial newspapers. Though several months old, it usually took up more than a full page of a typical four-page issue.

During the summer of 1773, both versions of the Virginia Gazette tracked debates in Parliament about how to support the East India Company. Teetering on the brink of collapse, the EIC could not sustain its business without what we would today call a bailout. From Virginia, readers could track the public discussion about the EIC, its finances, and how to rescue it. In early September, for instance, Clementina Rind posted an accounting of Company investors:

As the crisis continued, no one knew for sure what would happen. Americans loved drinking tea. According to historian James Fichter, at least a quarter of colonists drank tea each day. They consumed over half a pound of leaves per person per year.2 At the same time, many in London were aware of American opposition to many imperial policies. In the December 2 issue, Clementina Rind reprinted the pertinent question from an early September London paper:

Click to read more

December 9, 1773: Slow News Week

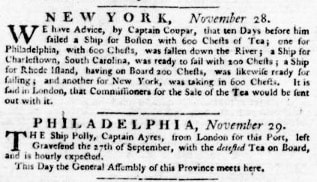

Some weeks, there just wasn’t much news to print. Despite intense activity elsewhere, the second week of December appeared as a quiet moment in the Tea Crisis on the pages of Williamsburg’s two newspapers. Clementina Rind offered just a few reports about the destination of the tea ships. One reprinted from a New York newspaper dated November 18 drips with dramatic irony:

This report is an excellent example of how time lags worked. On November 18, the New York paper was correct in

reporting that no tea had arrived in Boston. But in the three weeks it took for the news to appear in the

Virginia Gazette, all three ships—the Dartmouth, Beaver, and Eleanor—docked at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. And

Virginians wouldn’t learn that news for another week.

News came first to busy port cities like Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Charleston. But Williamsburg was

located miles from the Atlantic coast. Since the postal service was unreliable and bad weather could cause long

delays, news was sometimes slow to arrive in Williamsburg. Nevertheless, printers had to produce an issue every

week with four pages of news, essays, and advertisements.

In this case, the lack of news about tea did not reflect an overall absence of news from London. Purdie and

Dixon included a full page of reports ranging from late July to late September on the front page of the December

9, 1773, issue of their Virginia Gazette. The topics were eclectic, as usual. Purdie and Dixon reprinted news

about war in Poland, protests in Dublin, an epidemic outbreak in Baghdad, and the Pope’s suppression of the

Jesuit order.

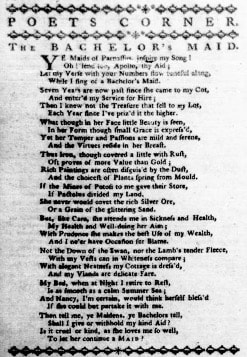

But this particular issue lacked news from North America. In a week when there wasn’t news to publish, printers

compensated in a variety of ways. With some of the space available, Purdie and Dixon published a poem entitled

“The Bachelor’s Maid,” in which a man imagines that his maid, whom he has employed for seven years, must desire

to be his wife. It is . . . probably satirical.

Fortunately for Purdie and Dixon, they had developed a deep and broad base of advertisers. Their December 9

Virginia Gazette included nearly two-and-a-half pages of advertisements of various kinds. Merchants offered

their goods—many recently arrived from Europe. Individuals sought to sell land, animals, furniture, and other

property.

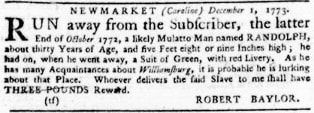

Many of the ads related to slavery. Virginia’s economy depended on enslaved labor. Each issue of the Virginia

Gazettes included numerous offers of enslaved people for sale, and rewards for the capture of runaways, often

using the same language as nearby calls for the return of missing horses.3

To the modern eye, these advertisements are jarring. To a Virginian in 1773, they were commonplace, and likely

aroused more interest in the reward than they did disgust at the descriptions of people as property. Tea,

tobacco, enslaved people: to many colonists, these were on the same level and required similar attention.

Go deeper: Human bondage touched every aspect of life in

eighteenth-century Virginia. Explore how slavery shaped the production and content of the Virginia Gazettes.

Click to read more

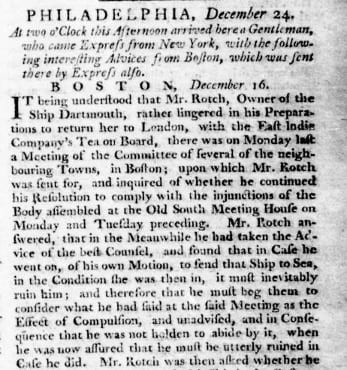

December 16, 1773: First Reports of the Tea Ships

In Williamsburg on December 16, 1773, Virginians finally began to get accurate news about the tea ships headed to other ports in North America—just as Bostonians were dumping the tea overboard. We only know this was accurate in retrospect, of course. At the time, no one knew just yet if the news carried in the Virginia Gazettes was reliable.

The East India Company loaded tea onto seven ships bound from London across the Atlantic in the fall of 1773. One was destined for each of Charleston, Philadelphia, and New York; four carried tea to Boston. Of that group, all but one successfully reached their destinations, though only five were able to tie their ropes at a wharf. On December 16, the news from around the colonies began to coalesce around those facts, with multiple news stories from a variety of sources in each paper confirming some portion of those details.

Boston news from November 18 in Purdie & Dixon’s Virginia Gazette identified the ship captains as

“Bruce, Hall, and Coffin, . . . having each of them, as we hear, a Number of Chests of Tea from the East India

Company” and headed for the town.

From New York under a November 28 dateline came additional word of ships, though with wildly inflated totals for

how much tea each was carrying (600 chests on one ship, when in total Bostonians destroyed 340 across three

ships). On November 29 a Philadelphia paper reported that it awaited the arrival of the Polly “with the detested

tea on board.” With the ships identified, residents of Williamsburg and surrounding areas in Virginia could only

wait to find out what would happen when dockworkers tried to unload the tea.

Click to read more

December 23, 1773: No Christmas Break

In the eighteenth century, many American colonists devoted less time to Christmas than Americans do in the twenty-first century. A newspaper published a few days before the holiday therefore looked basically the same as one from the rest of the year: no special advertisements, no seasonal graphics. As Christmas approached in 1773, Virginians continued to learn more about the tea crisis.

Rumors from London, for example, emphasized American opposition to the tea. One news item, reprinted in both newspapers, suggested that colonists would reuse the familiar protest tactic of the boycott: “The American Colonies are expected soon to enter into a general Association not to import any Tea from England, till they have obtained the Redress of certain Grievances which they now complain of.”

In New York, which was more loyal to the crown than New England, Governor William Tryon defused the crisis by storing the shipped tea at a fort. Nevertheless, there was opposition to the tea in New York. The two Gazettes reprinted the same paragraph from early December, which identified the three agents for East India Company tea as Henry White, Abraham Lott, Benjamin Booth. However, the paragraph also noted that all three declined, citing “general Opposition” to the tea.

Boston, meanwhile, had few updates. In early December, the various sides were at a standoff. The Sons of Liberty would not let the tea land. Customs officials would not allow the ship owners to unload any cargo unless they brought the tea with it. And the governor would not allow the ships to leave without clearing customs. The crisis had already come to a head in Boston. But Virginians would only learn about it slowly.

Click to read more

December 30, 1773: A Constitutional Catechism

Two weeks after Bostonians actually dumped tea into the harbor, colonists in Virginia were still only learning about events from the very beginning of December, just as the standoff was beginning. Readers of either newspaper could learn something about the protests against the tea and about the negotiations that had started. Numerous officials were involved, including Governor Thomas Hutchinson, the tea agents, the owners of the three ships, and town leaders.

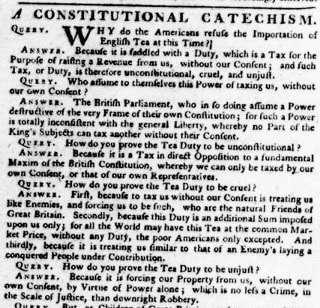

Alexander Purdie and John Dixon published a commentary on the Tea Crisis called “A Constitutional Catechism.” Modeled on the call-and-response used in Christian churches for worshippers to confirm their beliefs, this “catechism” instead related how and why colonists opposed the tax on tea.

“Why do the Americans refuse the Importation of English Tea at this Time?” read the first question. “Because it is saddled with a Duty,” came the response, “which is a Tax for the Purpose of raising a Revenue from us, without our Consent; and such Tax, or Duty, is therefore unconstitutional, cruel, and unjust.” After years of protesting various taxes imposed by Parliament—on goods from sugar to paint—colonists were quite familiar with this argument.

The dialogue led readers through the reasons why the tea was unjust (“Because it is forcing our Property from us”) and why they should resist. “Is it not incumbent upon us,” one question posed, “to defend our common Property from all such Impositions,” referring to laws that were deemed “unconstitutional, cruel, and unjust.”

“Yes,” was the expected reply, “because it is as much the Duty of the whole People to defend and preserve their common Property as it is that of an individual to defend and preserve his private Property.” That opinion was not shared universally in the colonies, but it drove many of the protestors to act.

Click to read more

January 6, 1774: The Fate of Boston’s Tea

Just one week into 1774, Virginians received news that would come to define the entire year in North America. With the arrival of a post rider, colonists finally learned the fate of the tea in Boston. Nestled under the Williamsburg heading on page three of the January 6 issue was the first report of what would eventually be known as the Boston Tea Party.

Just one week into 1774, Virginians received news that would come to define the entire year in North America. With the arrival of a post rider, colonists finally learned the fate of the tea in Boston. Nestled under the Williamsburg heading on page three of the January 6 issue was the first report of what would eventually be known as the Boston Tea Party.

All that Purdie and Dixon could report at that point was a one-paragraph statement issued by the Boston Committee of Correspondence. After negotiations failed, “a Number of People huzzaed in the Street, and in a little Time every Ounce of the Teas on Board the Captains Hall, Bruce, and Coffin, was immersed in the Bay, without the least injury to private Property.”

That notice was just one document that traveled in the satchel of Paul Revere. A frequent messenger for the Committee of Correspondence, he left Boston on the morning of December 17 to bring news of the events of the previous night to the south and west. He arrived in New York on December 22, and either he or another rider reached Philadelphia on December 24. More detailed reports would follow shortly. For now, Virginians knew the fate of the tea.

Click to read more

January 13, 1774: Politics and Tea

Unless they had another source of news, readers of the two Virginia Gazettes had to wait a full week after the first reports of Boston’s action against the tea to learn more. The issues of January 13, 1774—four weeks after Bostonians dumped the tea into the harbor—contained much fuller accounts of what happened in Massachusetts.

Sometime during the second week of January, additional newspaper reports arrived in Williamsburg from Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. The news traveled in multiple ways outward from Boston. In Virginia, therefore, Clementina Rind and Purdie & Dixon had many options for how to tell the story.

Purdie & Dixon drew their reports from the pro-revolutionary Pennsylvania Journal. Under a heading of “Philadelphia, Dec. 24,” they included several reports from Boston. First, they republished an account of the town meeting and dumping of the tea on December 16, largely taken from the Massachusetts Spy. They also included news about a group of colonists who had burned a shipment of tea in Lexington, a town about fifteen miles from Boston. Finally, they brought the story of Philadelphia’s protests up to the 24th: residents knew the tea ship would arrive any day and the protesting colonists had called a town meeting for December 27.

Purdie and Dixon also included one original note from Williamsburg, indicating that “a correspondent” wrote to them “That he hopes the Virginians, celebrated for their Patriotism, will immediately follow the illustrious Example of the People to the Northward, and totally decline the Use of all East India Tea, which is pregnant with Mischief to the Health and Liberties of the People of America.”

Clementina Rind was a bit more circumspect. She did not include an account of the Tea Party in her issue that day. She did, however, publish some material that originated with Patriots, including a long essay written by someone using the pseudonym “HONONCHROTONTHOLOGOS.” Among the alarming allegations in the piece, the author suggested that British army units were preparing to enforce the law in Boston: “the Ladies are apprehensive,” he wrote, “that the musty Teas kindly conveyed to them from London, will be crammed down their throats with all expedition.” As the winter wore on, both Virginia Gazettes would return to the perspective of women, a crucial audience for publications and for tea consumption.

The dialogue led readers through the reasons why the tea was unjust (“Because it is forcing our Property from us”) and why they should resist. “Is it not incumbent upon us,” one question posed, “to defend our common Property from all such Impositions,” referring to laws that were deemed “unconstitutional, cruel, and unjust.”

“Yes,” was the expected reply, “because it is as much the Duty of the whole People to defend and preserve their common Property as it is that of an individual to defend and preserve his private Property.” That opinion was not shared universally in the colonies, but it drove many of the protestors to act.

Click to read more

January 20, 1774: “no mail from the northward”

One of the key features of a newspaper—in colonial America and since—is its regular publication schedule. In the colonial era, nearly every newspaper published once a week. Because editors relied on getting news from other places, they usually timed their newspaper’s publication day to the arrival of a post rider. That meant that editors had a fresh supply of news to publish each week from elsewhere in the colonies and from Europe. In the winter, though, that could create a problem, because snow and ice could make travel slow and difficult. But whether or not the post rider arrived, readers expected another four-page issue each week.

Such was the case on January 20, when both issues of the Virginia Gazette reported that a “no mail from the

northward” had been delivered in the past week.

Purdie & Dixon did have a bit of news from Philadelphia, at least. In that city, news of the Boston Tea Party

arrived literally hours before the tea ship headed for Philadelphia, named the Polly, appeared in Delaware Bay.

Patriots stopped the ship from proceeding to the wharves and brought the captain into town for a meeting on

December 27. At the meeting, colonists acted “with Unanimity, Spirit, & Zeal” to announce their opposition to

the tea and their desire that Captain Ayres should not attempt to land it. Armed with the news from Boston, they

were persuasive. Ayres agreed to return to London with the ship. In addition to congratulations, Philadelphians

agreed to help him restock the ship for the return voyage.

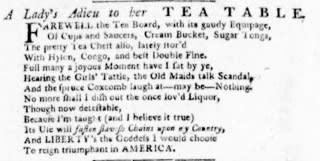

Purdie & Dixon also featured more poetry about the tea crisis. First, they published a piece entitled “A Lady’s

Adieu to her TEA TABLE.” In the poem, the unnamed female narrator described how she put away all the familiar

pieces of a tea setting: cups, saucers, utensils, a “pretty Tea Chest.” She thought back fondly to talking with

other women at the table, “Hearing the Girls’ Tattle, the Old Maids talk Scandal.” But she refused to serve tea

anymore, taking to heart the lesson of protests: Its Use will fasten slavish Chains upon my Country,

Purdie & Dixon also included another piece of verse in the form of lyrics to a song, depicting the Boston rebels as heroes. The song was written to be sung “to the plaintive Tune of Hosier’s Ghost.” Most Americans knew a small handful of melodies, and poets would write their verses to be sung to one of them. (Think today about how “the ABC’s” and “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” have the same melody.)

Click to read more

And LIBERTY’s the Goddess I would choose

To reign triumphant in AMERICA.

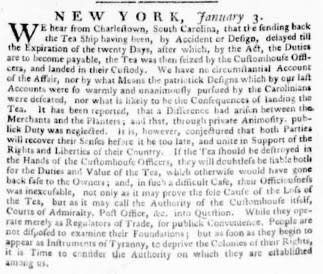

January 27, 1774: News from Charleston and New York

Through November and December of 1773, most newspapers focused their attention on the crisis in Boston. It offered drama, high stakes, and a set of characters who were easily identified by their role. By late January 1774, Virginians knew what there was to know about Boston’s dumping of the tea. Throughout North America, colonies awaited word about how the British government would respond. But they all knew it would be months before they heard anything.

In the meantime, Purdie, Dixon, and Rind turned more of their attention to events elsewhere in the colonies. Charleston, South Carolina, for instance, also had a strong reaction to the arrival of tea, but for the most part the Virginia Gazettes relegated this coverage to the back burner. In South Carolina, a single tea ship, the London, arrived in the harbor on December 1. The laws required the same steps as in Boston: the ship captain, Alexander Curling, had to supply a list of goods to the customs officer in Charleston (including 257 chests of tea). The customs officer would collect duties before allowing the ship to unload its cargo. Because of the time lag to get information between Charleston and Boston, the two cities acted simultaneously and without any knowledge of what the rebels in the other town were doing.

The activities in Charleston show the possibility of how to resolve a standoff in a much different political environment. As both Williamsburg newspapers reported in their January 27, 1774, issues, the tea merchants in Charleston, “finding that their receiving the said Consignment would be generally disagreeable to the Inhabitants, declined having any Thing to do with it.” Customs officials refused to let the ship depart, but protesting colonists did not prevent the tea from reaching dry land. Therefore, “when the Time limited by Act of Parliament for paying the Duty expired, the Collector of his Majesty’s Customs, agreeable to the Laws in that Case made, landed the said Tea, and lodged the same in his Majesty’s Warehouse, where it now remains, the Duty there on not having been paid.”

Purdie and Dixon added one more paragraph, this one from New York, about the customs officials who were enforcing this law. They suggested that Americans should “consider the Authority” that created the customs laws because that officials were starting to “appear as Instruments of Tyranny, to deprive the Colonies of their Rights.” This argument would grow louder over the course of 1774 as more Americans began to call into question the basis of all British authority in North America.

Click to read more

February 3 and Beyond

Debate about the actions of Bostonians continued in February and March of 1774. On February 10, Purdie and Dixon published a response to an essay that they declined. The piece, signed by “A Virginian,” apparently expressed “Uneasiness” about what had happened in Boston. The writer—at least according to the two printers—was “apprehensive that some violent Measures would be adopted” in response, “which might end in the Annihilation of our American Legislatures, and introduce a military Government.”

Printers in colonial America usually claimed to be impartial, but in this case Purdie and Dixon publicly dismissed and mocked the writer’s arguments. They suggested that his predictions were “groundless” because the East India Company would never try again. The British government, meanwhile, was so dependent on trade with North America that they would never attempt harsh measures.

They were wrong.

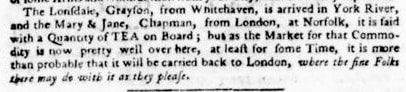

A few mysteries remained through the spring. The ship that sailed for New York in the fall didn’t arrive until late spring. Knocked off course by a storm in the Atlantic, Virginians only learned in late March from the Gazettes that the Lockyer had detoured to Antigua . . . over 1,700 miles south and east of New York City. In early May, news coverage began to boomerang as Virginians read about the London reaction to Boston’s dumping of the tea. The reports were dated from early February, which means that it took about six weeks for the news to reach London, and then another twelve or so to end up in Virginia.

In mid-May, Williamsburg residents learned along with their colonial brethren about the punishments for Boston. On May 19 Purdie & Dixon reprinted several paragraphs from London newspapers with details on “the American bill” that would punish Boston. Within a few weeks Virginians learned the full story: Parliament had closed the port of Boston, restricted the government of the entire colony of Massachusetts, and imposed military rule. The House of Burgesses, the Virginia colonial assembly that met in town, called for a congress to convene and respond jointly.

Then in August, finally, a tea ship arrived in Virginia. Purdie and Dixon announced in their August 18, 1774, issue that they expected that it would not be made available for sale. Instead, they expected the tea would be returned to London, at which point they didn’t care what happened to it.

Click to read more

Conclusion

It’s difficult to say when the Tea Crisis “ended.” It didn’t really. The Continental Congress that Virginia requested met in Philadelphia in September 1774. War was not inevitable. But the crisis escalated to fighting by the next spring.

Looking at these months of crisis from Virginia helps us understand how colonial Americans experienced political events. Watching from Williamsburg, Virginians had to piece together information from afar that arrived in small chunks. They had to be information literate in order to determine whether to believe what they were reading in the newspaper, in private letters, or hearing at the tavern and coffee shop.

It was hard work to be part of a political community that extended hundreds of miles along the coast of North America and thousands of miles across the Atlantic Ocean. As colonists participated, many of them decided they no longer wanted to be subject to the decision-makers in London.

Learn More

Sources

Joseph M. Adelman is an associate professor of history at Framingham State University. He is the author of Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789 (2019).

- For more on newspapers in revolutionary America, and in particular the Virginia Gazettes, see Joseph M. Adelman, Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019); Jordan E. Taylor, Misinformation Nation: Foreign News and the Politics of Truth in Revolutionary America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022); Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America, with a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers, 2 vols. (Worcester: Isaiah Thomas, Jr., 1810); Karen A. Weyler, Empowering Words: Outsiders and Authorship in Early America (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 2013); Leona M. Hudak, Early American Women Printers and Publishers, 1639-1820 (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1978); King, Martha J. “Clementina Rind: Widowed Printer of Williamsburg,” in Cynthia A. Kierner and Sandra Gioia Treadway, eds., Virginia Women: Their Lives and Times. Volume 1 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015); David A. Rawson, “Printing in Colonial Virginia,” Encyclopedia Virginia.

- James R. Fichter, Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023), 25.

- For more on slavery advertisements in colonial American newspapers, see the Slave Adverts 250 project by Carl Robert Keyes.