We all know about the Boston Tea Party. When Bostonians disguised as “Mohawk” warriors destroyed British East India Company (EIC) tea in their town’s harbor, the British Parliament reacted sharply. The government’s response sparked new forms of resistance to imperial rule. For that reason, the Boston Tea Party is sometimes seen as the opening salvo in the American Revolution. But the Boston Tea Party was only one event in a larger crisis. During the fall of 1773 and the winter of 1774, American colonists debated whether they should pay taxes, acquiesce to British commercial policy, and otherwise accept imperial control over their affairs.

Roots of the Tea Crisis

By the early 1770s, Americans had become avid consumers of tea. The British East India Company supplied some of the product, but colonists also purchased tea in large quantities—some legal, much of it not—from other suppliers. Buying large quantities of Dutch tea, Americans ignored laws that required them to pay duties on imported consumer products. But lax enforcement meant that imperial officials largely ignored the practice. Though the American colonies formed a small part of the global tea market, the British North American colonies were saturated with the brewed beverage.

British officials knew about the American thirst for tea. They attempted to leverage that fact as they constructed policies after the Seven Years’ War to encourage American compliance with imperial policies. Parliament had taxed tea as part of the 1767 Townshend Act. When Parliament repealed those duties three years later, they left the tax on tea intact as a statement.

In 1773, Parliament worked to bail out the East India Company, which had fallen into deep financial trouble. Its troubles came out of an extensive drought in the Bengal region from 1769 to 1770, corruption within its leadership, and a massive oversupply of tea languishing in London warehouses. Officials decided to bring together the American love for tea with the Company’s need to dispose of its excess supply by including provisions in its bailout that gave the EIC an exclusive market in the North American colonies. Many colonists objected to these measures. The result was the Tea Crisis, one of the sparks that lit the American Revolution.

London, England

1600

Founded by royal charter, the East India Company (EIC) became England’s (and then Britain’s) commercial connection to the Indian and western Pacific Oceans. As a joint stock company, the EIC drew investors and shareholders from across the British elite, including members of Parliament. By the early eighteenth century, the EIC was conducting a massive trade in tea, spices, and other goods between India, China, and Britain.

North American Colonies

1730s-1740s

During the middle decades of the eighteenth century, American colonists consumed increasing amounts of tea. Trade of the leaves to North America became far more profitable not only for the British East India Company but also for traders from other commercial powers, in particular the Dutch. Merchants in Atlantic ports advertised the many varieties of tea for sale alongside other goods imported from Europe.

London, England

1767

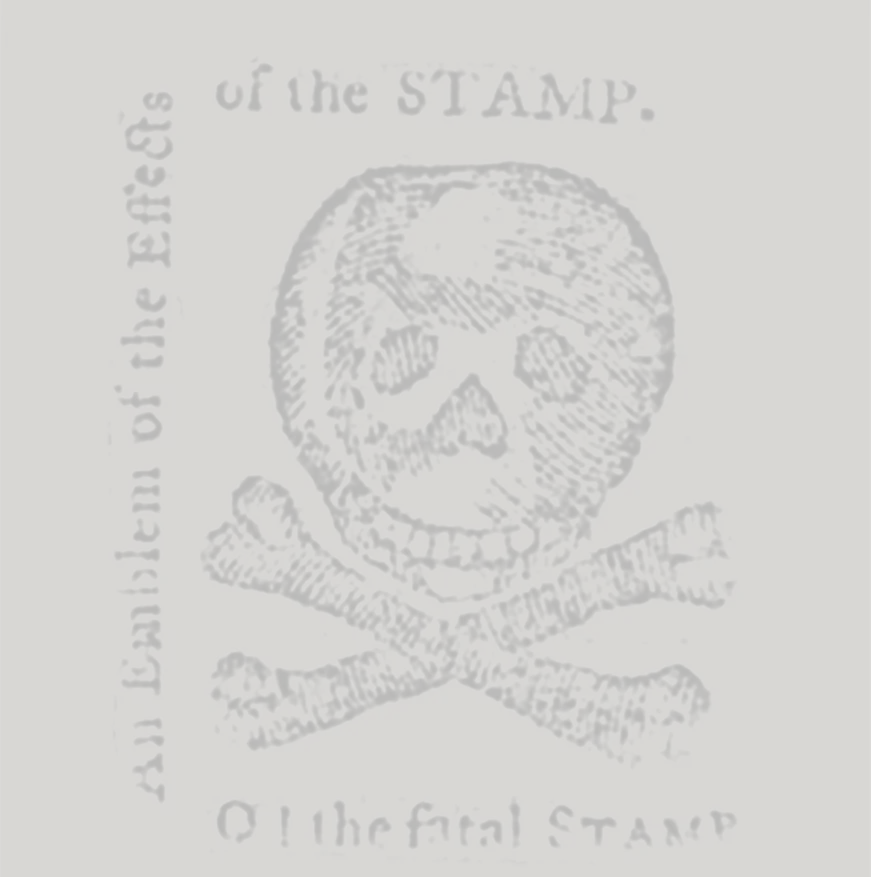

Despite the repeal of the Stamp Act a year earlier—or perhaps because of it—British officials continued to seek ways to tax the colonists. They needed to produce revenue and also establish Parliament’s authority.

The new chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend, had not only these goals in mind but also broader imperial reforms. He devised a set of duties on imported goods, which Parliament adopted as a Revenue Act in the spring of 1767. The duties fell on a wide range of products, including lead, paint, paper, china . . . and tea. Within months, the Sons of Liberty and other anti-imperial groups attempted to relaunch protest efforts. They called for boycotts of British goods. They pressured merchants to sign non-importation agreements. They also sought to disrupt the collection of the taxes. And though Townshend died only months later, American colonists associated these particular taxes with him.

India

1769-1770

Across two years, a catastrophic drought struck Bengal, a region in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. The drought triggered a famine that killed millions of Bengalis. It also dried up the tea crops that the East India Company relied on for trade. The drought and famine exacerbated already growing financial problems for the EIC. Would they go bankrupt?

London, England

March 5, 1770

On the same day that the Boston Massacre occurred thousands of miles away, the House of Commons voted to rescind nearly all the duties under the Townshend Acts. The new prime minister, Lord North, recognized the reality that the duties simply were not being collected because of the protests and boycotts from many of the North American colonies. This repeal aimed to cool temperatures in the debate over imperial policy and administration. Nonetheless, Parliament maintained a duty on imported tea to make the statement that it did indeed have the right, as per the 1766 Declaratory Act, to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

A Crisis Brews

The financial crisis for the East India Company came to a head in the spring of 1773. Its difficulties threatened much of the British economy—not to mention the accounts of its many shareholders, some of whom sat in the House of Commons.

For weeks members debated how to respond to the crisis, whether to rescue the EIC, and if so with what measures. In the end Parliament adopted a multi-pronged strategy. First, it floated a loan to the EIC to cover its immediate shortfalls. Second, it lowered the duty on tea imported into the North American colonies to make the price of British tea more palatable to the American market. Finally, it supported the EIC’s efforts to clear its overflowing warehouses by reinforcing its monopoly to sell tea in the North American colonies.

Ministers authorized the EIC to name agents in the colonies who would pay the duty, receive the tea as wholesalers, and then distribute it elsewhere in the colonies.

Williamsburg

1773, October-November

During the fall of 1773, news reports began to trickle into the colonies about the Company’s plans to send tea to North America. Tracking those shipments involved an elaborate guessing game. Which ships would carry the tea? How much was coming? In Virginia, readers followed the details of the Tea Crisis through the incomplete and sometimes-inaccurate reports of the Virginia Gazette. Follow along with them in our project on the Tea Crisis in the Virginia Gazette.

Boston

1773, November 28

After months of speculation and waiting, the first ship laden with tea arrived in a North American port as the Dartmouth docked at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. The ship was immediately met by a detachment of the Sons of Liberty, who refused to allow the captain to begin unloading his goods for customs inspection and payment of duties.

The next day, a town meeting at Faneuil Hall directed that a guard continue to stand watch twenty-four hours a day, lest either the tea commissioners or customs officials attempt to move the cargo. The town meeting also called for the resignations of the commissioners appointed to accept the tea, who included some of the leading Loyalists in Boston: Thomas and Elisha Hutchinson (two of the sons of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson), Richard Clarke and sons, Joshua Winslow, and Benjamin Faneuil Jr.

Boston

1773, December 1-15

Over the ensuing three weeks, daily drama plagued Boston. Under British customs law, the cargo on board the Dartmouth needed to be processed by customs officials within twenty days of its arrival. Otherwise, the officers could seize the ship and its cargo. If that were to happen, the tea would be under the control of imperial officials and Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Radical leaders were not sure that their fellow colonists would resist the sale of tea. The town meeting repeatedly demanded that Governor Hutchinson or the Boston customs agent release the ship and allow it to return to England before the December 17 deadline arrives. They repeatedly declined.

In Charleston, South Carolina, a tea ship landed on December 1, prompting another round of protests. As in Boston, a standoff ensued wherein the governor and customs officer would not allow the ship to leave, and the Sons of Liberty would not permit anyone to unload the tea.

Boston

1773, December 16

December 16 marked the twenty-day time limit for the Dartmouth, the first tea ship to arrive in Boston, to clear customs and pay duties on the items in its hold. Boston radicals continued to refuse to allow the tea to land. Governor Hutchinson and customs officials would not let the ship leave without unloading and paying the taxes. According to reports, ship owner Francis Rotch spent the day shuttling the eight miles between the Old South Meeting House in Boston and the Milton estate of Hutchinson, attempting in vain to find a solution.

According to legend, Samuel Adams gave a prearranged signal and the town meeting dispersed as night fell. More likely, protestors had already decided to act if no solution appeared. Within a few hours, dozens of young men, their faces blackened and their clothing disguised to make them look like “Mohawks,” descended on Griffin’s Wharf where the ships had moored. They proceeded to open 340 chests of tea and dump them into Boston Harbor.

Charleston

1773, December 17-22

The dispute in Charleston occurred simultaneously with events in Boston. But neither city had any knowledge of events in the other.

Charleston’s tea crisis unfolded in a less violent fashion. On December 17, Sons of Liberty forced the tea consignees (Roger Smith, Peter Leger, and William Greenwood Jr.) to resign their positions so that there would be no one available to accept the tea even if it were landed. That effort proved fruitless just a few days later. Eventually, the customs officer Robert Halliday seized the ship and its tea cargo for non-payment of duty and had the tea offloaded into a colony-controlled warehouse near the harbor.

New York and Philadelphia

1773, December 24-27

Paul Revere departed Boston on the morning of December 17, 1773, with news of the action against the tea. He arrived in New York three days later, delivering messages to the New York Committee of Correspondence, and then continued to Philadelphia. On Christmas Eve he handed copies of the Massachusetts Spy, handwritten reports, and possibly his own account to William Bradford, the printer of the Pennsylvania Journal. Bradford published the news as a one-page broadside with the title, “A Christmas-Box for the Customers of the Pennsylvania Journal.”

The very next morning, Christmas Day, the Polly, bearing tea destined for Philadelphia, arrived in Delaware Bay. Armed with information about how Boston leaders played their hand, Philadelphia’s radicals convinced Ayres to land his ship outside the radius that required registration with customs. They brought Ayres to town for a meeting where, with “unanimity, spirit, and zeal,” the assembled crowd urged him to turn around and return to London with his cargo. Knowing what had just happened to the northeast, Ayres agreed and returned to his ship and (presumably unhappy) crew.

Steeped in Revolution

The radical decision to destroy the East India Company’s tea continued to have repercussions in Boston through the winter months. With a travel time of approximately eight weeks in each direction, residents knew it would be months before they learned how Parliament and the EIC would react to the events of December.

Boston

1774, January-February

In mid-January, the Boston town meeting voted to ban the sale of tea altogether in the town, lest any illicitly obtained EIC tea end up brewing in a Bostonian’s pot. Barely a week later violence erupted again after a confrontation between George Robert Twelves Hewes, a shoemaker who participated in the tea’s destruction, and John Malcom, a local customs officer and loyalist. In their dispute on the street, Malcom struck Hewes with his cane, severely injuring him. In response, the Sons of Liberty captured Malcom, dragged him through town, and tarred and feathered him. Political disputes were turning violent.

New York

1774, January-February

Throughout the winter, New York continued to await the arrival of its tea ship, the Nancy. Unbeknownst to local residents, the Nancy had been blown off course by storms on its Atlantic journey. It ended up docking at Antigua in February, almost two thousand miles south of New York’s harbor. The ship would only arrive in New York later in the spring.

London

1774, January-February

News finally began to arrive in London about the events of December in Boston, Charleston, and Philadelphia. Infuriated members of Parliament immediately began to debate how to punish Boston for the destruction of thousands of pounds of tea. The EIC demanded financial restitution for Boston and asked the British Treasury to auction the tea that government officials had sequestered in Charleston.

London

March 31, 1774

News finally began to arrive in London about the events of December in Boston, Charleston, and Philadelphia. Infuriated members of Parliament immediately began to debate how to punish Boston for the destruction of thousands of pounds of tea. The EIC demanded financial restitution for Boston and asked the British Treasury to auction the tea that government officials had sequestered in Charleston.

London

March 31, 1774

After weeks of deliberation, the House of Commons responded to North American protests with the Boston Port Act. Designed explicitly as a punishment, the Act required the town of Boston to pay restitution to the East India Company in the amount of £9,659, which would cover the cost of the 340 chests of tea and the amount of duty that would have been collected under the Tea Act. Beginning on June 1, 1774, the Act ordered the port of Boston closed to traffic until that sum of money was raised.

That spring Parliament adopted several other laws known (to the revolutionaries) as the “Coercive Acts” or the “Intolerable Acts.” The Massachusetts Government Act placed the entire colony under a military governor. The Impartial Administration of Justice Act moved trials for maritime issues from the colonies to London. The Quartering Act cemented the ability of the British Army to lodge soldiers in private homes when stationed in the colonies. The Quebec Act formed a government for the French Canadian territories that Britain had claimed at the end of the Seven Years’ War, which seemed dangerous to many colonists who opposed toleration of Catholic subjects.

Boston, Massachusetts

May 13, 1774

Bostonians knew that Parliament would react to the dumping of the tea. Five months later that reaction arrived in the form of two laws. The first, the Boston Port Act, ordered imperial officials to shut down all maritime traffic through the port beginning on June 1 until the East India Company received financial restitution for the tea cargoes it had lost in December.

The second, the Massachusetts Government Act, replaced the civilian governor—most recently Thomas Hutchinson, who had already left for England—with a military government under General Thomas Gage. Gage had spent a significant part of his Army career in North America, including as Commander in Chief of British Army forces on the continent.

Boston, Massachusetts

June 1, 1774

Just weeks after learning about the Boston Port Act, residents of the town faced the sudden closure of its wharves to commercial traffic as the Act took effect. Though rumors circulated that some leading men in town had offered to cover the cost of the tea dumped in December 1773, no payments occurred.

With the port closed, Boston was connected to the rest of the world only via Boston Neck, a thin strip of land just wider than the road that carried traffic between the town and the rest of Massachusetts. Within weeks, other colonies offered shows of support, sending supplies to the town both by land and via Salem, Plymouth, and other coastal towns.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

1774, September-October

Responding to a call from Virginia’s House of Burgesses, representatives from twelve colonies gathered at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, just across the street from the State House. There they convened as a Continental Congress. Meeting for about six weeks, the delegates considered a range of proposals to protest Parliament’s legislation of that spring.

Though a group of radicals urged a hardline response, the Congress included members who were far more moderate and even Loyalist. Led by Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, this group thwarted the most combative responses. By the time the Congress left Philadelphia in late October, they adopted several measures. First, they approved a boycott of British imported goods across the colonies. Second, they drafted a petition to King George III outlining their complaints. Third, they wrote to American colonists to explain their decision. Finally, they drafted a proclamation to colonists in Quebec that invited them to join the anti-imperial cause.

North America

1774, November-December

Inspired by compatriots in larger towns, Americans in various towns across the colonies continued to act against imported tea. For example, in November a group of colonists dumped two tea chests into the York River in Virginia, in what is known as the Yorktown Tea Party.

The next month, a ship bearing tea arrived at the small port of Greenwich, New Jersey, on the shore of Delaware Bay. A group of patriots seized the cargo, brought it to the town square, and publicly burned it. As the diarist Philip Vickers Fithian noted the next day: “Last night the Tea was, by a number of persons in disguise, taken out of the House & consumed with fire.”

In 1774 and early 1775, other towns that took action against tea cargos included Chestertown, Maryland, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

March 1, 1775

The most significant development to come out of the meeting of the Continental Congress in the fall of 1774 was the Continental Association, an agreement among the twelve colonies present to establish a massive general non-importation and non-consumption agreement. That took effect on March 1, 1775. Patriots in each colony formed Committees of Safety to manage the association locally. Tea was, of course, one of the headline consumer products banned under the Association.

Learn More

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Further Reading

Robert J. Allison, The Boston Tea Party. Applewood Books, 2007.

Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party & the Making of America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

James R. Fichter, Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023.

Jane T. Merritt, The Trouble with Tea: The Politics of Consumption in the Eighteenth-Century Global Economy. Studies in Early American Economy and Society from the Library Company of Philadelphia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Mary Beth Norton, 1774: The Long Year of Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020.

Sources

Joseph M. Adelman is an associate professor of history at Framingham State University. He is the author of Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789 (2019).

Cover image: Detail from “The Tea-Tax-Tempest, or Old Time with his Magick Lanthern,” anonymous artist (1783). This print was based on an earlier mezzotint by John Dixon. Courtesy: The Met Museum.