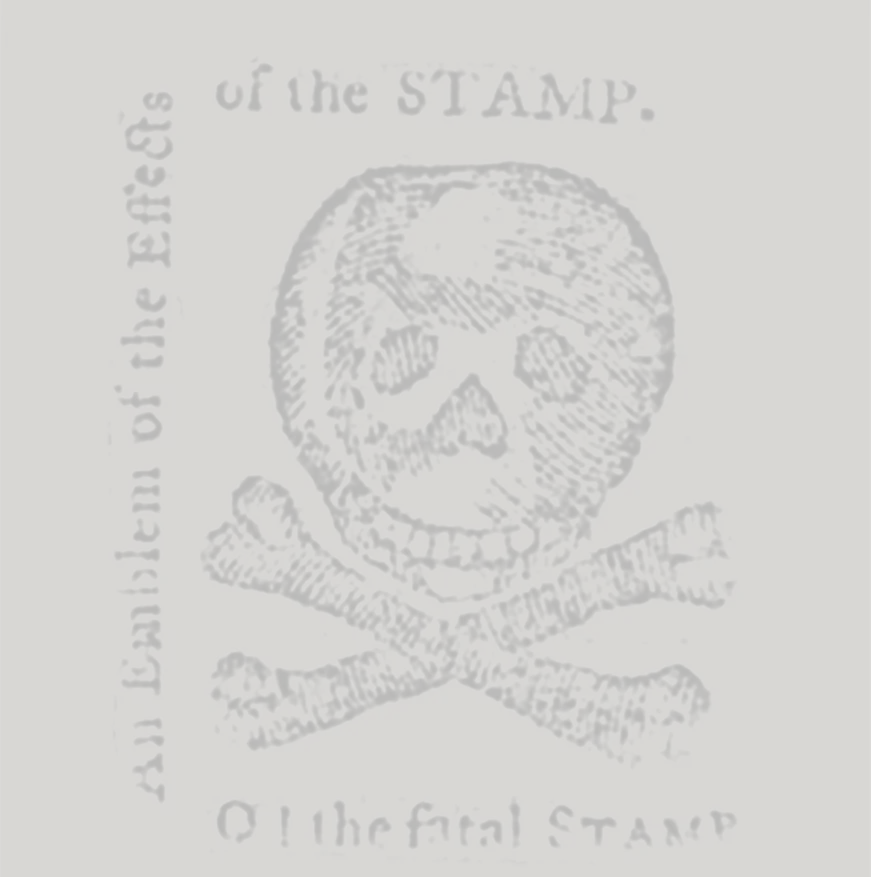

American colonists have been taxed by Parliament with duties associated with trade or commerce before, but the Stamp Act is different. While it might seem to be a small tax for the gentry, for the less wealthy it is a significant burden. Virginia is a credit economy in which middling folks often use the courts to collect debt. The Stamp Act promises to add to those costs. The Stamp Act sets a troubling precedent for a legal system driven by precedent, the colonists feel they are no longer in control of their own legislation—a right granted them as Englishmen. Nobody could know it then, but coordinated resistance against the act will set in motion actions that will eventually lead to revolution.

New Beginnings

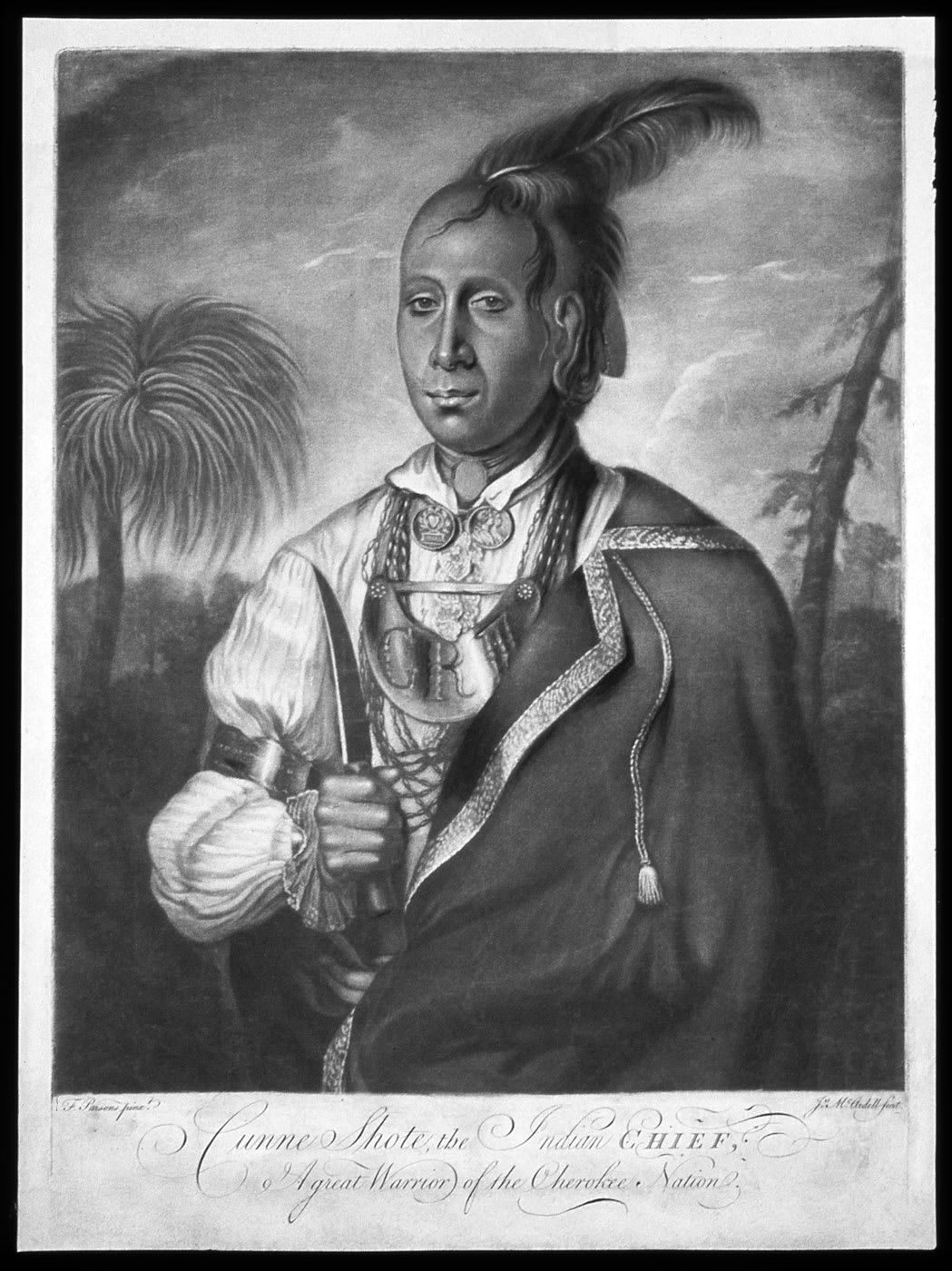

In 1760 the future looks bright for a twenty-two-year-old young man who is crowned King George III of Great Britain and Ireland. Great Britain is on the victorious side of a war that stretches across the world from the European continent to the Americas, Africa, and India. In North America, the British have invaded Canada and French forces are on the road to defeat. Soon the Iroquois allies of the French will sign a peace treaty with Great Britain. The Following year George will marry seventeen-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz at the Royal Chapel in St. James’s Palace, London. By 1762 the Anglo-Cherokee war will be ended, following which a Cherokee delegation will visit that same young king in London, England.

Treaties

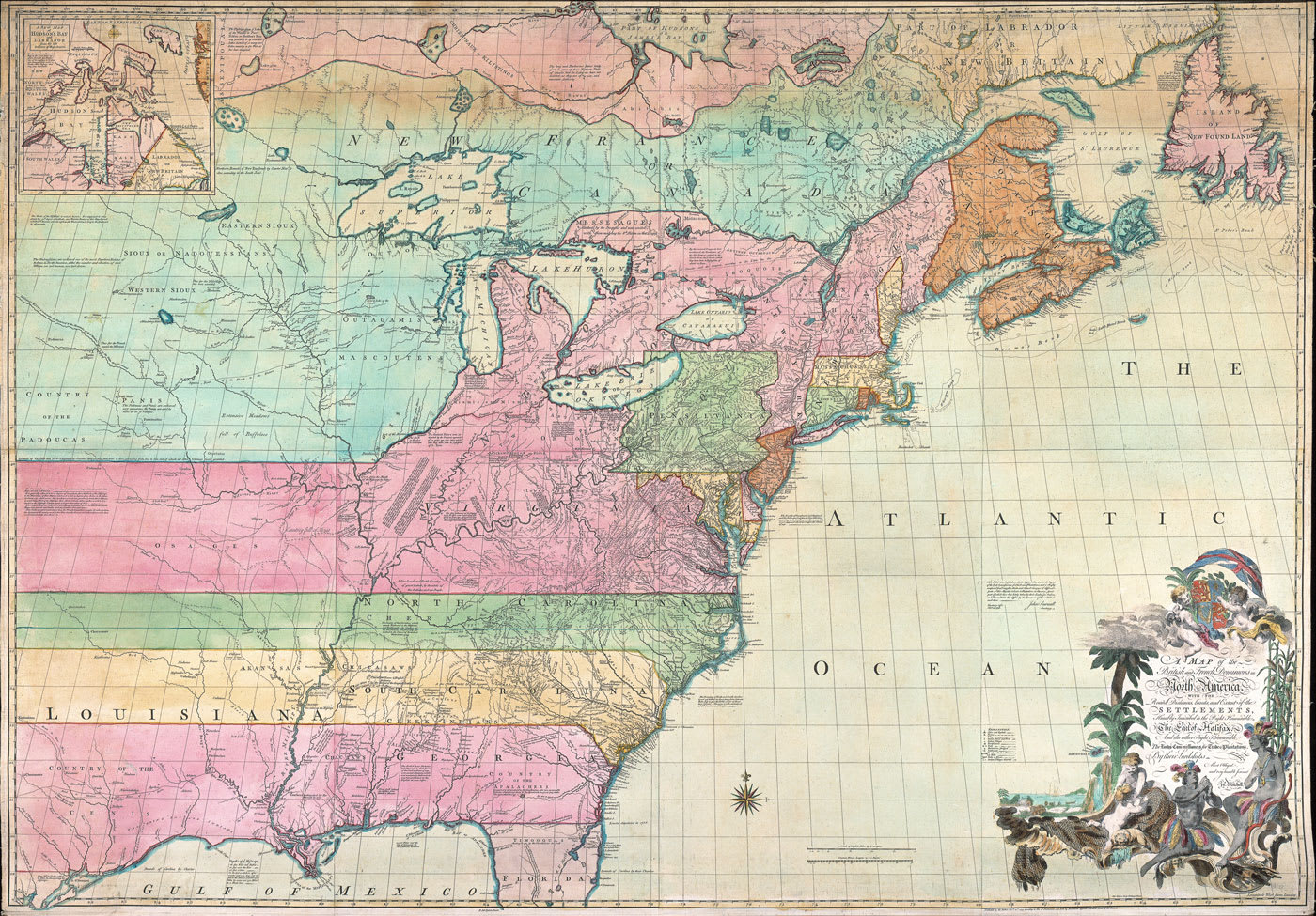

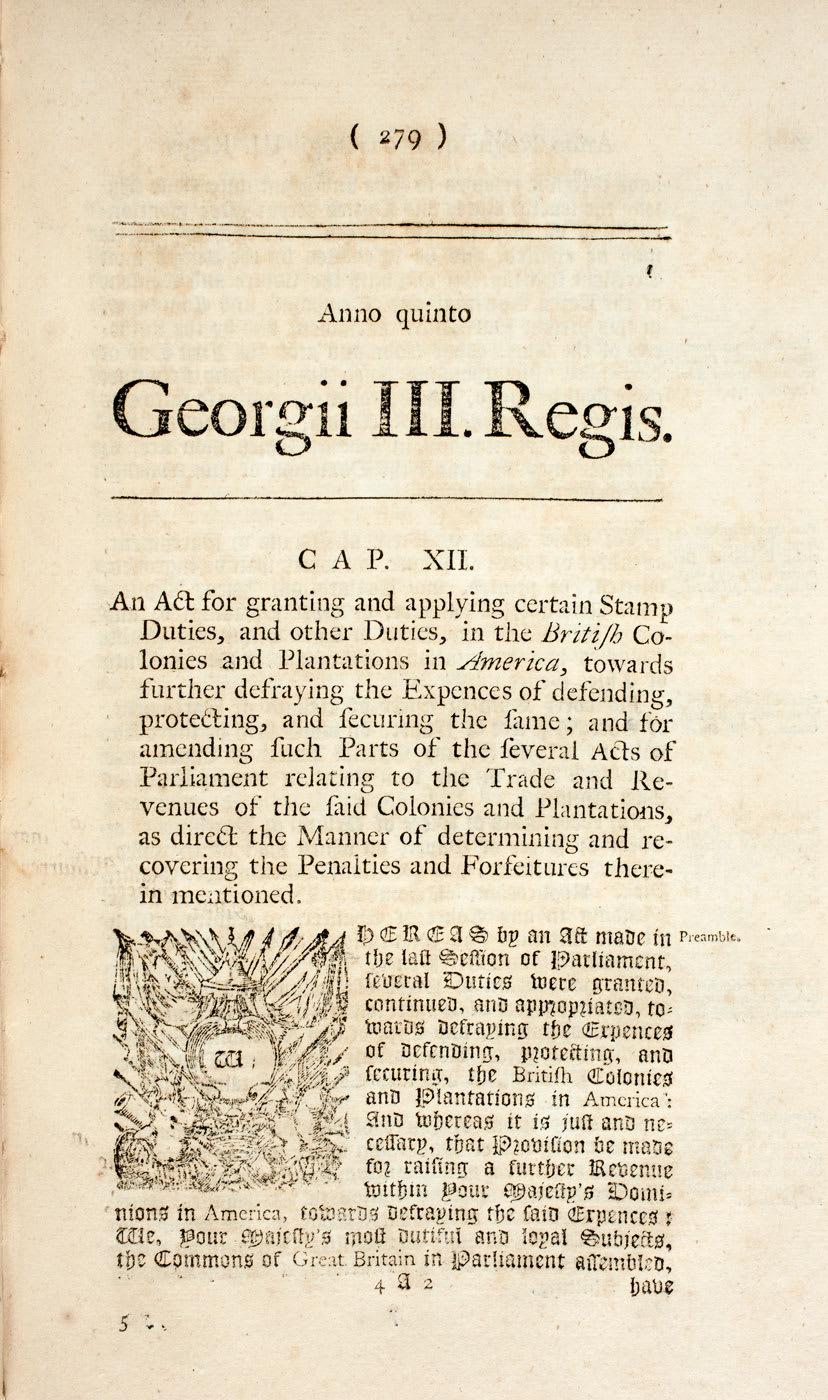

For the past nine years Parliament has been spending vast sums on a war that began on the American continent and spread across the world, becoming known as the Seven Years War. Now the British army has defeated the French in North America, which means the British Crown has increased its territory to almost the entire eastern third of the continent. This also means the country is broke. To help the country out of this situation, British Prime Minister Lord Bute institutes a tax on cider production in Britain, resulting in outrage and riots. Parliament also asks her British colonists to help pay for the protection of the newly acquired territories in America. Because the money was to be spent in America, Parliament sees no problem with Americans paying for this. Parliament plans to pass several acts to make colonists pay an extra tax to support their defense. For the colonists it marks a violation of their right as English subjects to be taxed only with their consent. It is the first of a chain of events that leads to American independence from Parliament—although at this stage no one foresees the consequences of these actions.

Opening Acts

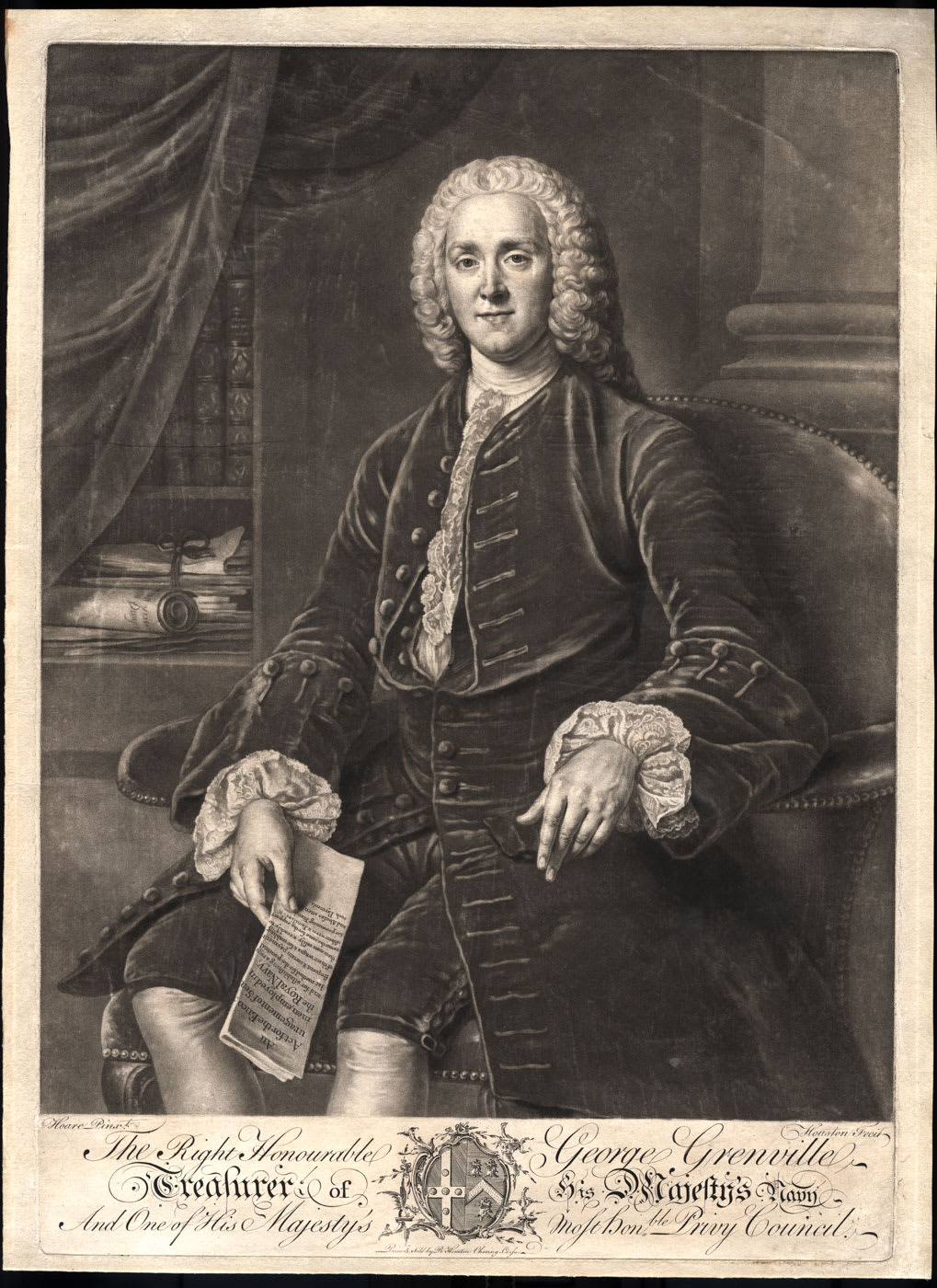

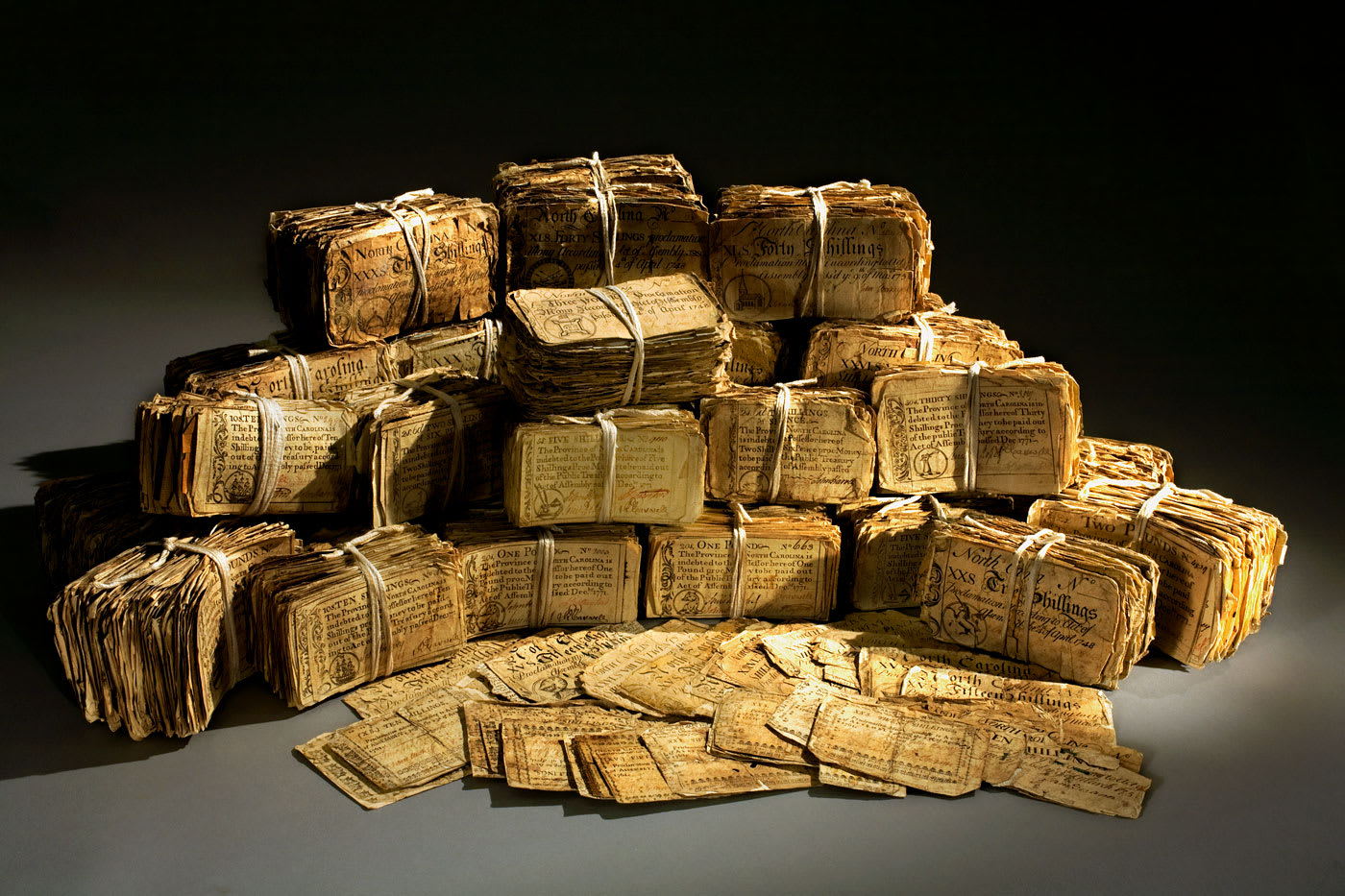

In Parliament, George Grenville announces the intention to renew the 1733 Sugar and Molasses Act by instituting the American Revenue Act. The act taxes sugar in an attempt to raise money to protect the colonies and to curb smuggling of sugar and molasses, but the action prompts protests in America instead. Another act, the Currency Act, is also extended, this time in an attempt to regulate paper money in the colonies. It too is quickly protested, and calls are soon made for its repeal. These acts steadily sensitize the colonies to future Parliamentary actions. Grenville’s proposals are direct taxes levied on everyday items. American colonists feel their rights have been trampled upon. When petitions are sent to Parliament from the American colonies, Parliament is perplexed by the colonists’ response. When the time comes, they will be prepared to protest the Stamp Act before it is even introduced.

Spring – The Act Initiated

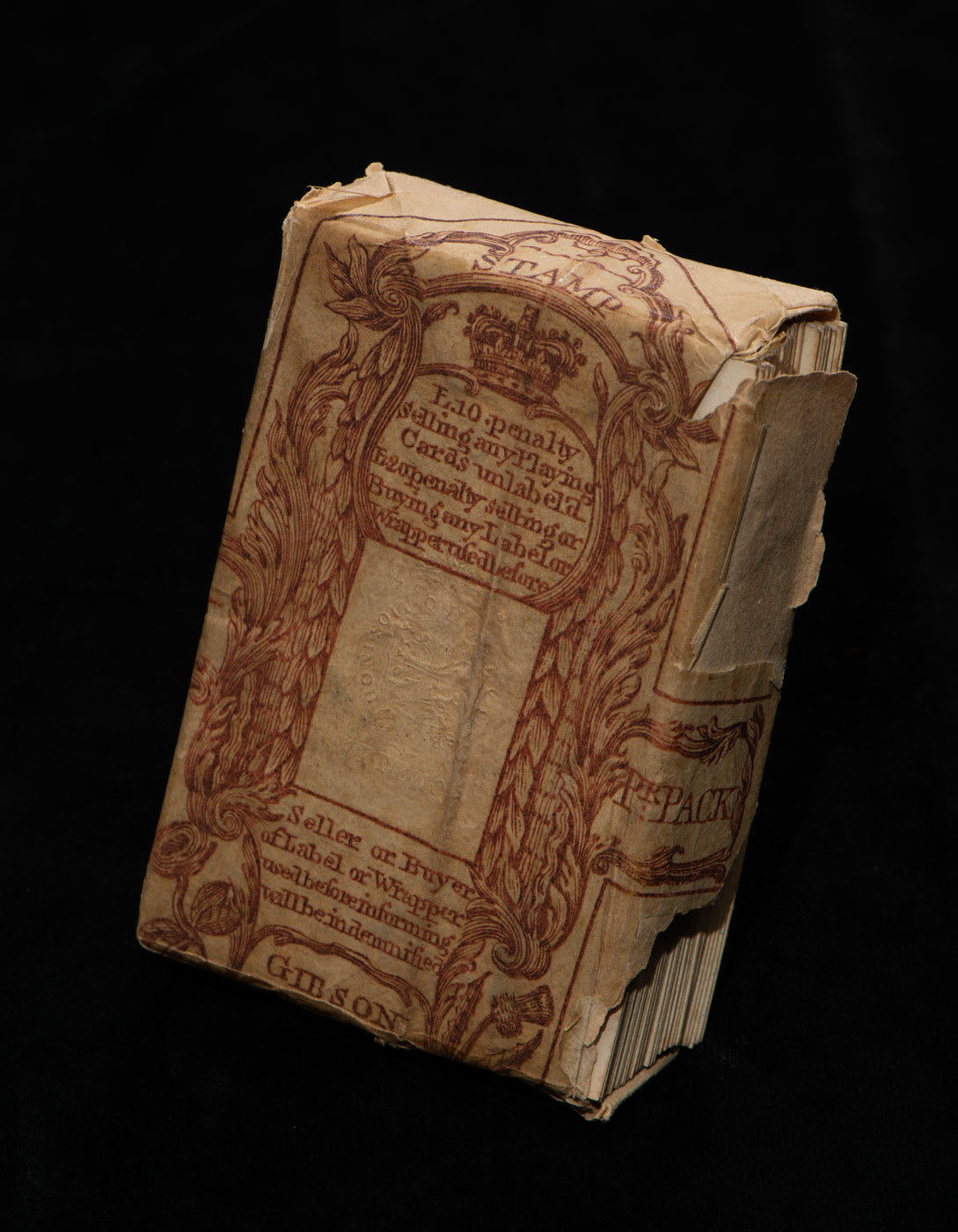

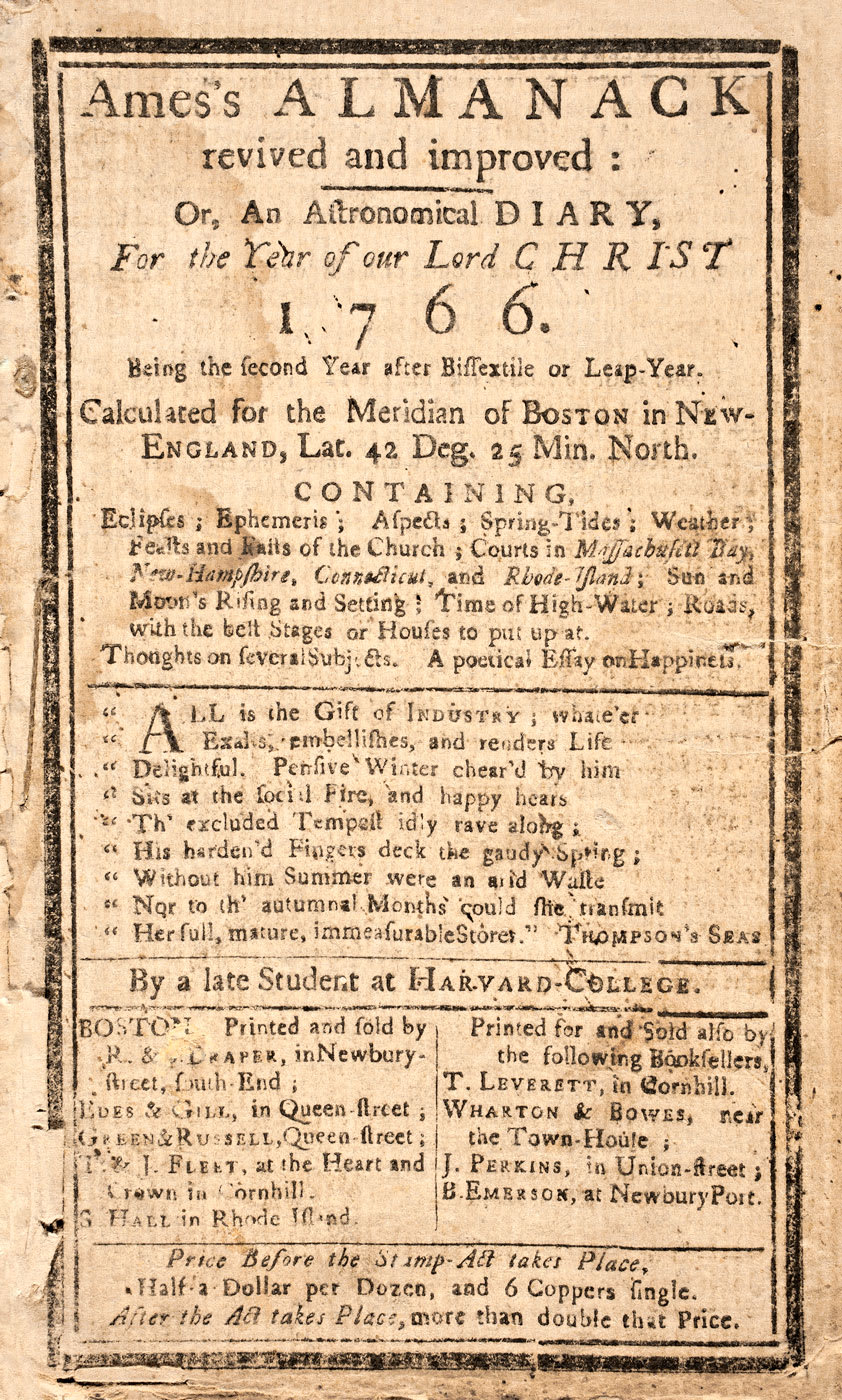

Parliament passes a further act that is to come into effect the following November. The Stamp Act is a tax on paper products like playing cards. Virginians are outraged because Parliament is continuing to attempt to legislate a tax without consulting them. Virginians are used to taxing themselves through their own local representatives in Williamsburg’s House of Burgesses — not by a Parliament reaching into their pockets from across the ocean. The tax will set a precedent in a legal system driven by precedents, and while it might seem to be a small tax for the gentry, for less wealthy it is a significant burden United in their protests, colonists from Boston, MA to Savannah, GA bully their respective stamp collectors into not commencing their duties. Only in Georgia is the stamp collector able to distribute the stamped papers, but he is forced to flee shortly afterwards.

Patrick Henry’s Role

It’s Patrick Henry’s birthday. Two months after the Stamp Act was passed in Parliament, Henry presents his provocative views on it at a meeting of Virginia’s House of Burgesses in Williamsburg, VA. Henry argues that colonists hold the same rights as the people of Great Britain, especially the right to only be taxed by their local representatives. When shocked representatives suggest some of his ideas amount to treason, he utters words that will become history, shouting, “If this be treason, make the most of it!” These “Stamp Act Resolves” are presented to the House of Burgesses for approval. They will be sent to England along with other grievances of the burgesses for the British government to see and consider a repeal. Henry presents in total seven resolutions, laying out his opposition to the tax, and four are accepted. Although they were not written for public consumption, selections of Henry’s fiery rhetoric begin to be published widely in newspapers throughout the colonies. Patrick Henry’s words are joined by propaganda, satire, slogans, and songs. A tax with obscure legislative roots has become a major barrier to good relations between Britain and its colonies in North America.

Autumn In Williamsburg

Merchants and gentry from across Virginia are meeting to do business in Williamsburg. They have been inflamed by the news of the Stamp Act. A crowd begins harassing a man as he walks from the direction of the Capitol down Duke of Gloucester Street. The group surrounds him, demanding to know if he will be commissioner in charge of introducing the Stamp Act in Virginia. He attempts to delay a response, saying he will answer them on Friday at ten o’clock once he has met with the colony’s royal governor. The mob is loud, it grows as it moves, and further demands are made of the man. The man didn’t know it, but another angry mob had just last month been organized to burn an effigy of him outside a courthouse about seventy miles north in Westmoreland. The man is Virginia-born George Mercer. Once a respected aide-de-camp to George Washington in the Seven Years' War, now he has recently been appointed government stamp tax collector for all of Virginia and Maryland. His is a figure of disdain.

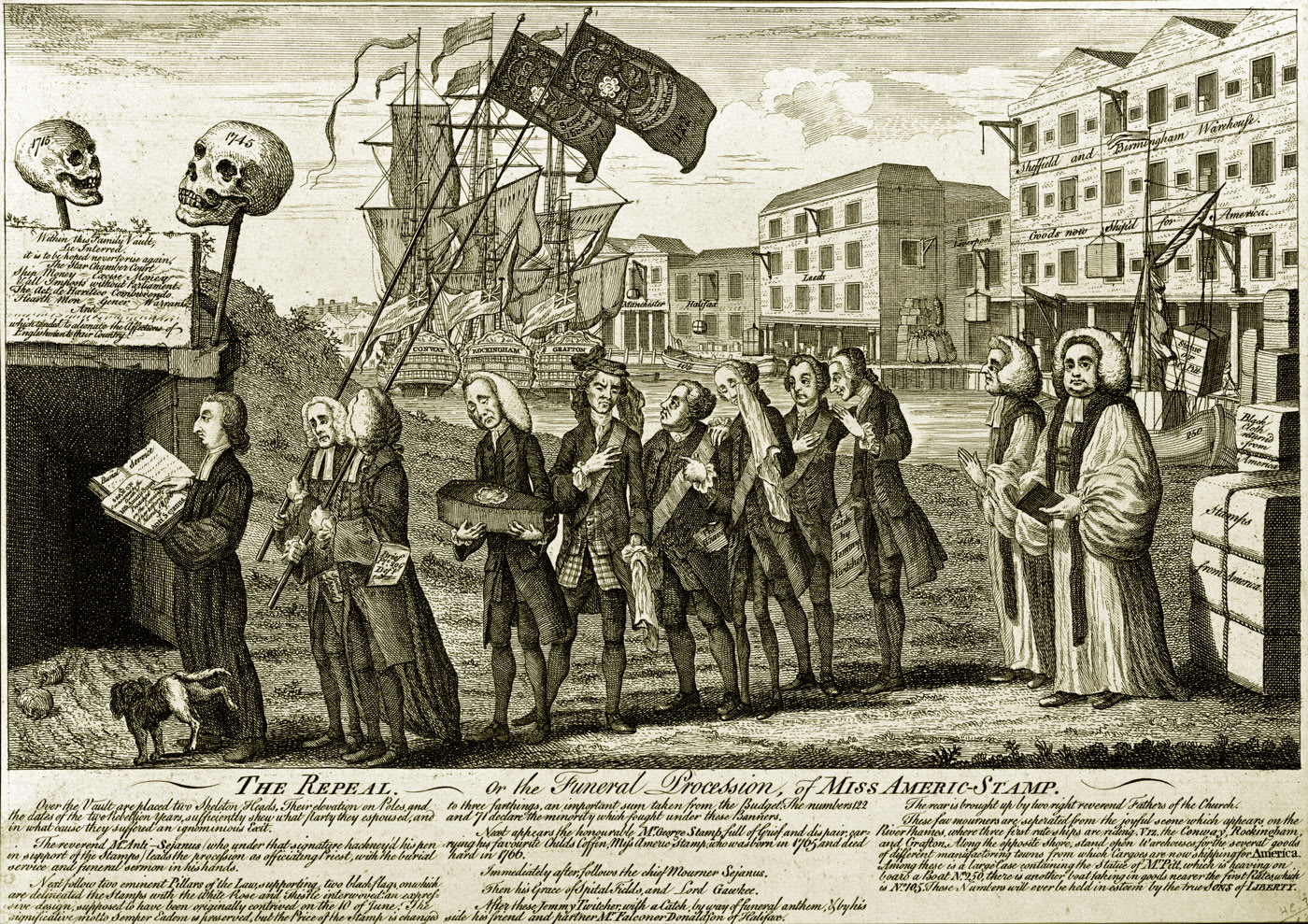

An Act Repealed, More to Come…

The British Parliament realizes its mistake and repeals the Stamp Act, but the damage is done. The effect of the act was to spur colonists to discover they have the power to unite against Parliament. Boycotts, “tea parties,” and slogans, and propaganda spreads through the colonies in newspapers and songs. Parliament has a different take on the repeal, passing the Declaratory Act, which states that it is still authorized to directly tax its colonies. After the repeal of the Stamp Act many colonists ignore the Declaratory Act, feeling the crisis is over and things can now go back to normal.

Over ... But Not Over

In 1767, another act, this time called the Townshend Act, is proposed by Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townsend. It attempts to collect taxes on tea, glass, lead, paint, and paper. John Dickinson, sometimes called “The Penman of the American Revolution,” publishes his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. These simply worded and concise editorials help to reignite the the tax protesters’ cause by suggesting the tax was not regulatory, but simply to raise revenue. Unrest was soon to follow. In the coming years, the events that began as noisy tax protests in the 1760s, would change their tone to calls for armed revolt.

Sources

“The Stamp Act,” America’s Homepage,https://ahp.gatech.edu/stamp_act_bp_1765.html (external link).

The Stamp Act, 1765,” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2012, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/inline-pdfs/03562.11_FPS_0.pdf (external link).

John Dickinson, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs, https://history.delaware.gov/jdp_main/dickinsonletters/pennsylvania-farmer-letters/ (external link).