Committees of correspondence have a long history in North America. For example, religious groups established corresponding societies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to coordinate activities around the Atlantic. In 1759, the Virginia House of Burgesses, Virginia’s colonial assembly, formed a committee of correspondence to communicate with and report on Virginia’s agent in London. Thus, by the time of the American Revolution, precedents existed for the revolutionaries’ creation of committees of correspondence. The first revolutionary committees of correspondence organized revolutionary ideas and actions within Massachusetts. In November 1772, Samuel Adams encouraged all towns in the Bay Colony to create committees of correspondence. He also asked these towns to share local happenings with the Boston Committee of Correspondence, which then read and reported what was happening in towns across the colony. On March 11, 1773, Virginia House of Burgesses members Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Dabney Carr gathered in Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern to consult on the need for each colony to form a committee of correspondence. In the face of parliamentary taxation and threats to their rights as Englishmen, these committees would communicate news from their region and help coordinate a united front across the British American colonies. This informal committee drafted a resolution that called upon Virginia and all other colonies to create committees of correspondence. The House of Burgesses approved this resolution on March 12, 1773 and all colonial assemblies, except for the Pennsylvania Assembly, adopted a version of this resolution. Committees of correspondence served as a first version of revolutionary government. In addition to collecting and communicating information, members discussed strategy with each other and between colonies. The following timeline highlights important events and activities in the history of what would become the revolutionary committees of correspondence system.

Virginia House of Burgesses’ Committee of Correspondence

In 1759, the Virginia House of Burgesses, Virginia’s colonial assembly, forms a committee of correspondence composed of four councilors and eight burgesses. The burgesses charge this committee with communicating with Virginia’s colonial agent in London and with reporting what that agent said to the House of Burgesses.

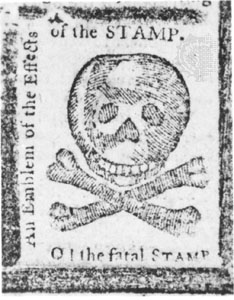

The Stamp Act Congress

Parliament passes the Stamp Act to help pay for military protection of its colonies in North America after the Seven Years' War (1754-1763). To coordinate a unified colonial protest movement against the tax, nine of eighteen British American colonies (including colonies in Canada and the Caribbean) elect representatives to meet in New York City. For more about the Stamp Act, visit the Stamp Act Timeline.

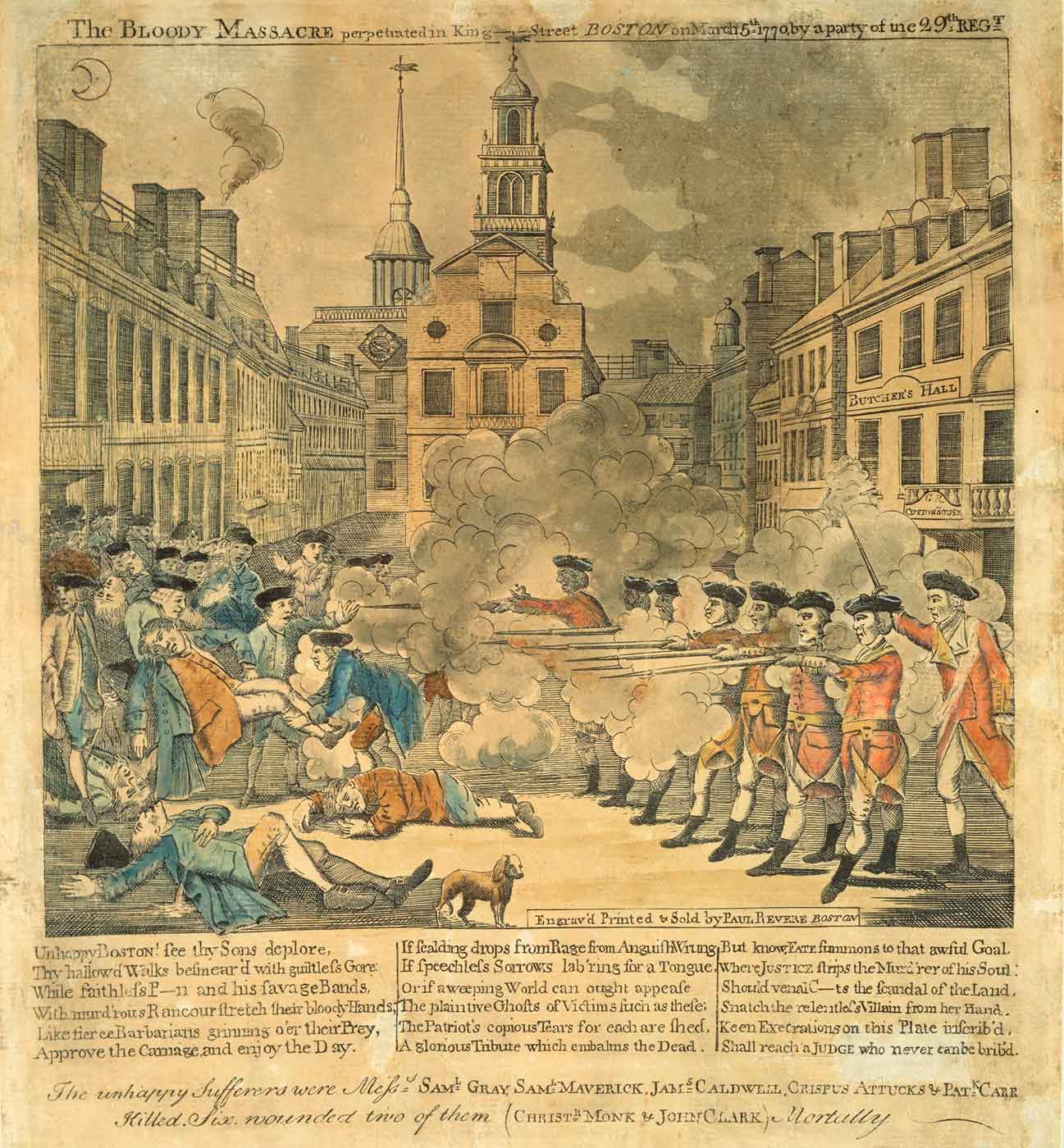

The Boston Massacre

On the evening of March 5, 1770, colonists taunt a British sentry in front of the Boston Custom House. The officer on duty, Captain Thomas Preston, and several British regulars march to his rescue. While attempting to rescue their fellow soldier, an angry crowd pelts the soldiers with rocky, icy snowballs, and acts aggressively with clubs and other tools. No one agrees on what precisely happened, but eight soldiers open fire and kill five members of the crowd. With the help of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere, the unfortunate shooting on Boston’s King Street becomes known as the “Boston Massacre.”

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Eric Hinderaker, a distinguished professor of history at the University of Utah and the author of Boston’s Massacre, assists our quest to discover more about the Boston Massacre.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Serena Zabin, a Professor of History at Carleton College in Minnesota and the author of the award-winning book, The Boston Massacre: A Family History, joins us to discuss the Boston Massacre and how she found a new lens through which to view this famous event that reveals new details and insights.

Activation in New England

Still reeling from the Boston Massacre, tensions between New England’s colonists and the Crown are at an all-time high by the Spring of 1772.

First Boston Massacre Oration

March 5, 1771

After the Boston Massacre and the repeal of the Townshend Duties (Parliament-imposed taxes on specific or “enumerated” goods), the revolutionary movement enters a quiet phase. Worried the movement of 1765–1770 was losing momentum, Samuel Adams and his colleagues turn the anniversary of the Boston Massacre into a day for public consideration of the colonists’ rights to rally support against what the revolutionaries see as parliamentary overreach in colonial governance. From 1771 through 1783, a prominent Bay Colonist/Stater commemorates the anniversary with an oration. After 1783, the city of Boston stops commemorating the massacre in favor of celebrating the Fourth of July.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Patrick Griffin, the Madden-Hennebry Family Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame and author of The Townshend Moment: The Making of Empire and Revolution in the Eighteenth Century, joins us to answer these questions as we continue our 3-episode investigation of the Boston Massacre.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

To conclude our 3-episode series on the Boston Massacre, we’re joined by Mitch Kachun, a Professor of History at Western Michigan University and the author of First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory.

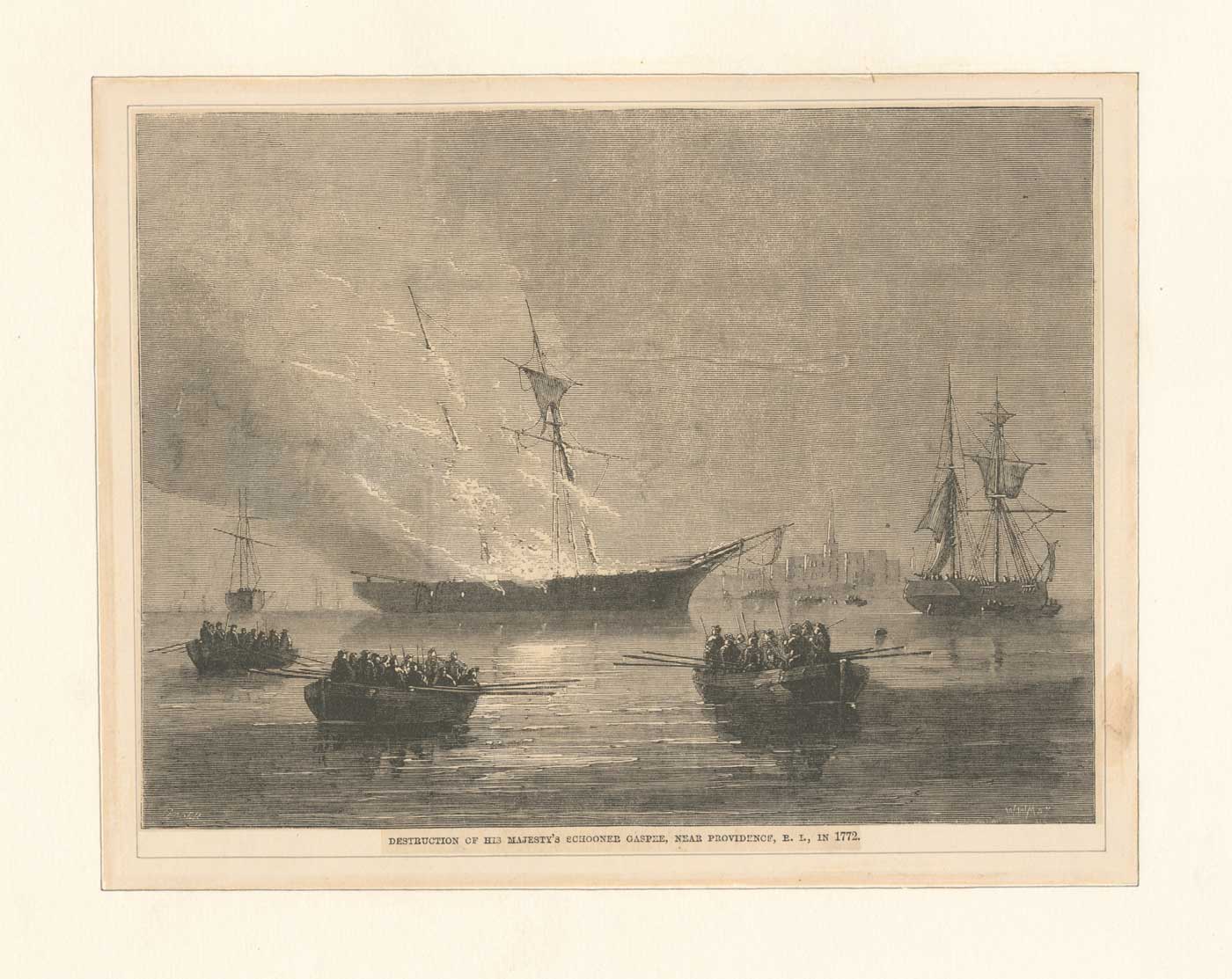

The Gaspee Affair

June 9, 1772

Smuggling to avoid government taxation has a long history in North America. To curb smuggling, the British government sends naval vessels to assist its customs officers in detecting and seizing ships with smuggled goods. In 1772, the British naval vessel Gaspee arrives to patrol Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay. The Gaspee's captain oversteps the law and stops ships without cause, physically abuses American sailors, and seizes goods he wants regardless of their legal status. On June 9, 1772, Rhode Island Captain Benjamin Lindsey refuses to stop at the Gaspee’s demand. Using his knowledge of the bay, Lindsey lures the Gaspee onto a sandbar, where it runs aground. Before the next high tide, a group of Rhode Islanders row out to the Gaspee, capture its crew, and set fire to the ship. After this incident, King George III calls for a trial in England of all the men involved in the “Gaspee Affair.” This event, and the king’s demands that colonists could and should be tried for capital crimes in England, captures the attention of many colonists, leading to the formation of the committees of correspondence network.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Fabrício Prado, Christian Koot, and Wim Klooster join us to explore the history of smuggling in the eighteenth-century Atlantic World and to investigate the connections between smuggling and the American Revolution.

Samuel Adams’s Boston Committee of Correspondence

November 1772

Inspired by the Gaspee Affair and a desire that more people in Massachusetts pay attention to imperial threats to their rights as Britons, Samuel Adams calls upon all towns within the Bay Colony to form committees of correspondence to share news. The Boston Committee of Correspondence compiles and disperses reports from towns across the colony.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

In this episode of the Doing History: To the Revolution series we explore governance and governments of the American Revolution with three scholars: Mark Boonshoft, Benjamin Irvin, and Jane Calvert.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Stacy Schiff, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, joins us to explore and investigate the life, deeds, and contributions of Samuel Adams using details from her book, The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams.

Virginia Leads the Charge

Over the course of 1773, colony after colony follows Virginia’s lead and appoints its own Committee of Correspondence. By the end of the year, colonists have moved that much closer to full rebellion.

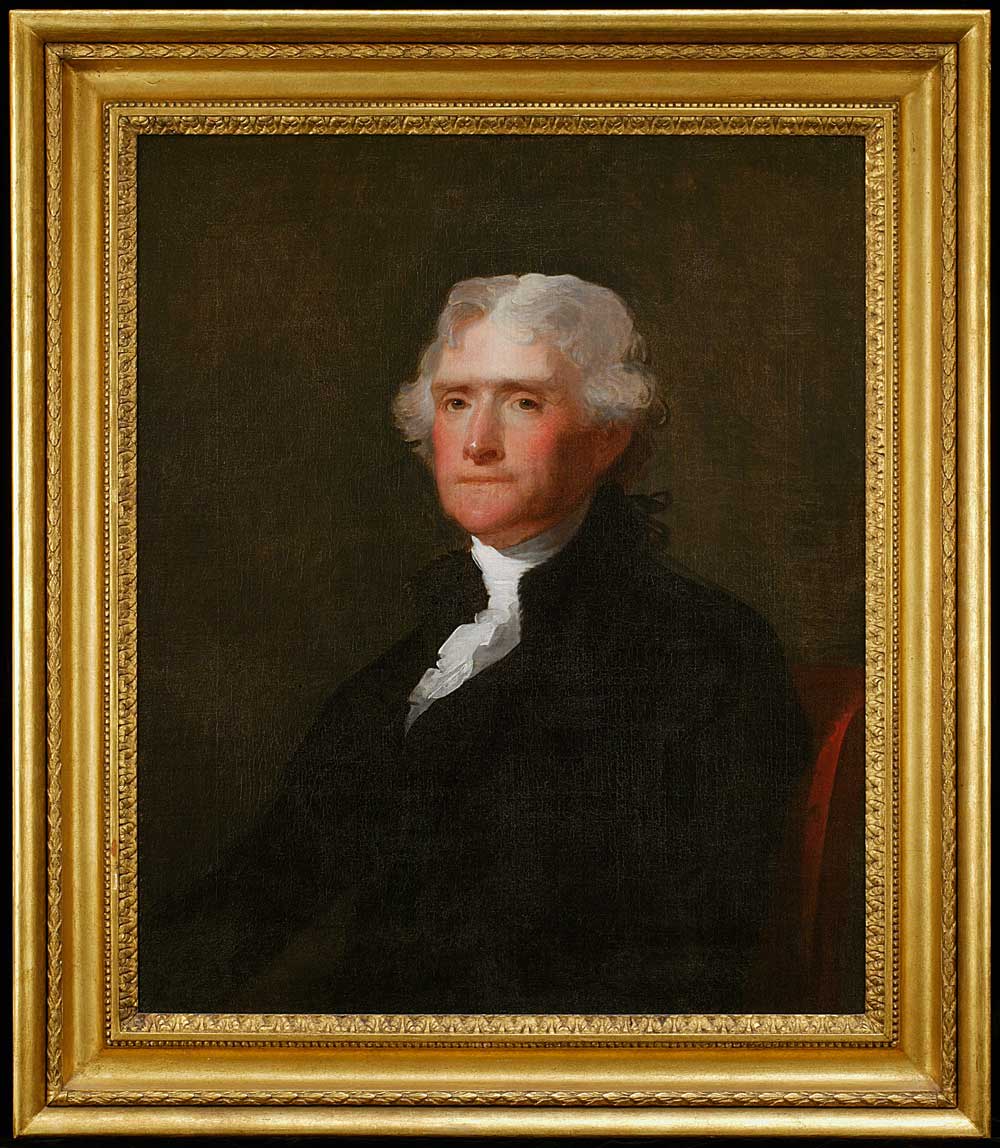

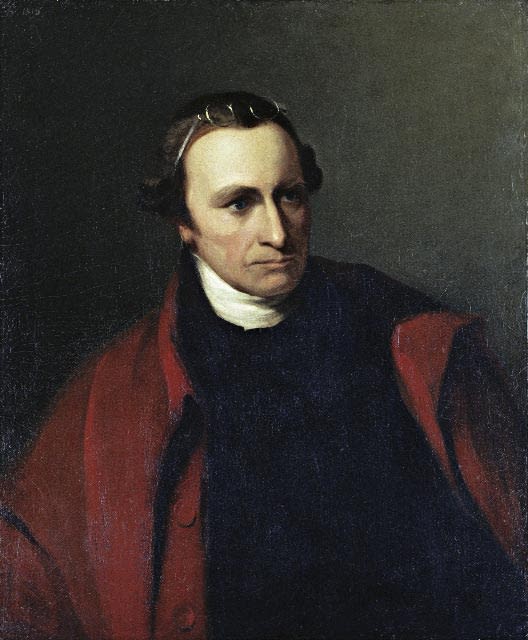

Informal Virginia Burgesses Committee Meets

March 11, 1773

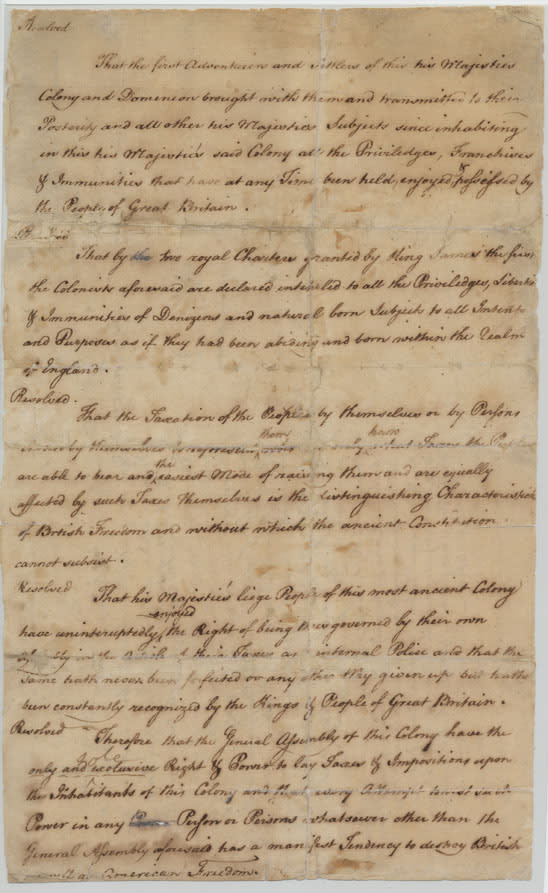

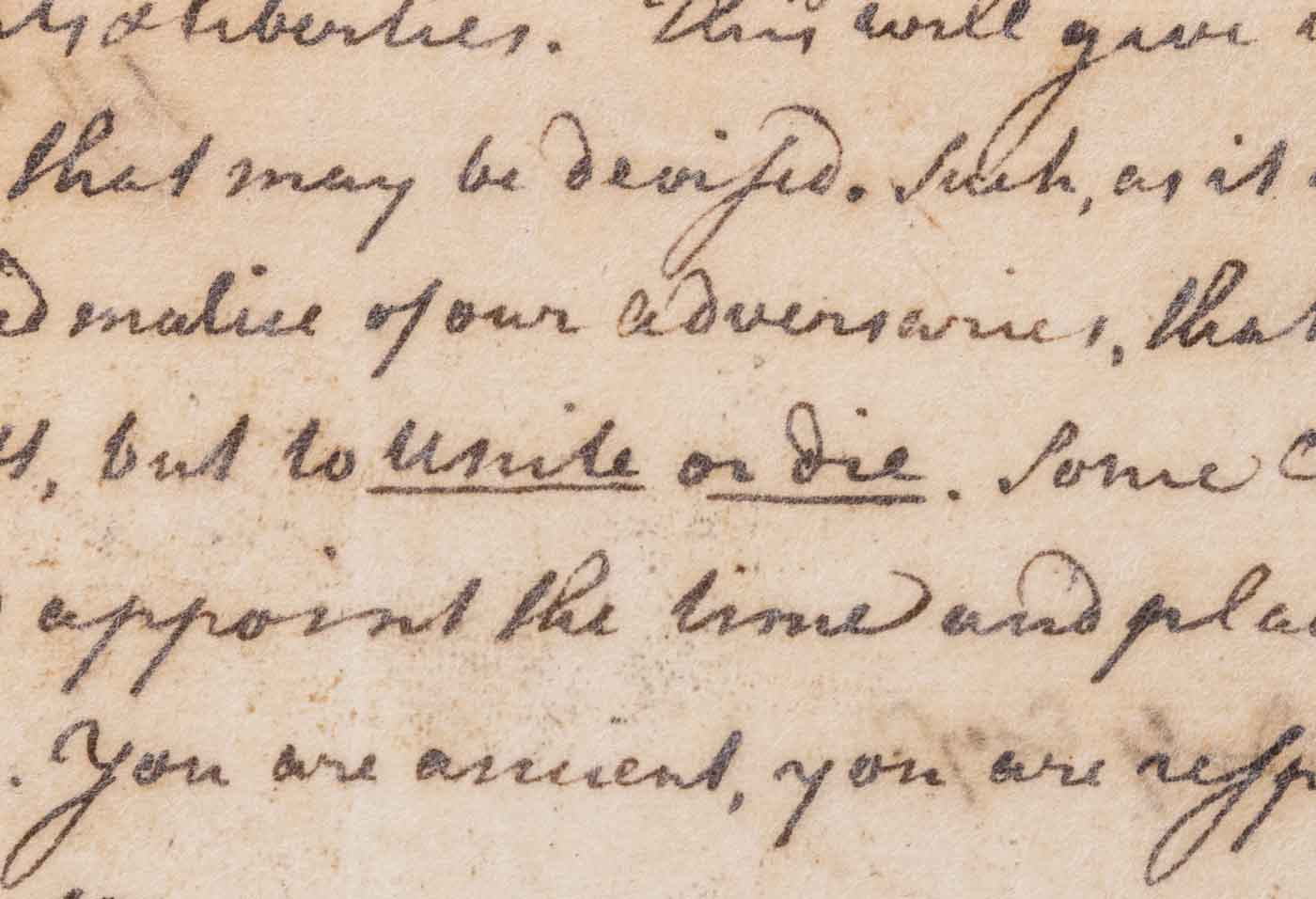

Several Virginia House of Burgesses members, including Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Dabney Carr, gather in Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern to consult on the need for each colony to form a committee of correspondence. Their hope is to coordinate a united front in the face of parliamentary taxation and threats to their rights as Englishmen. This informal committee drafts a resolution for the House of Burgesses to form a committee of correspondence for Virginia and for the Speaker of the House to invite all the other colonies to do the same.

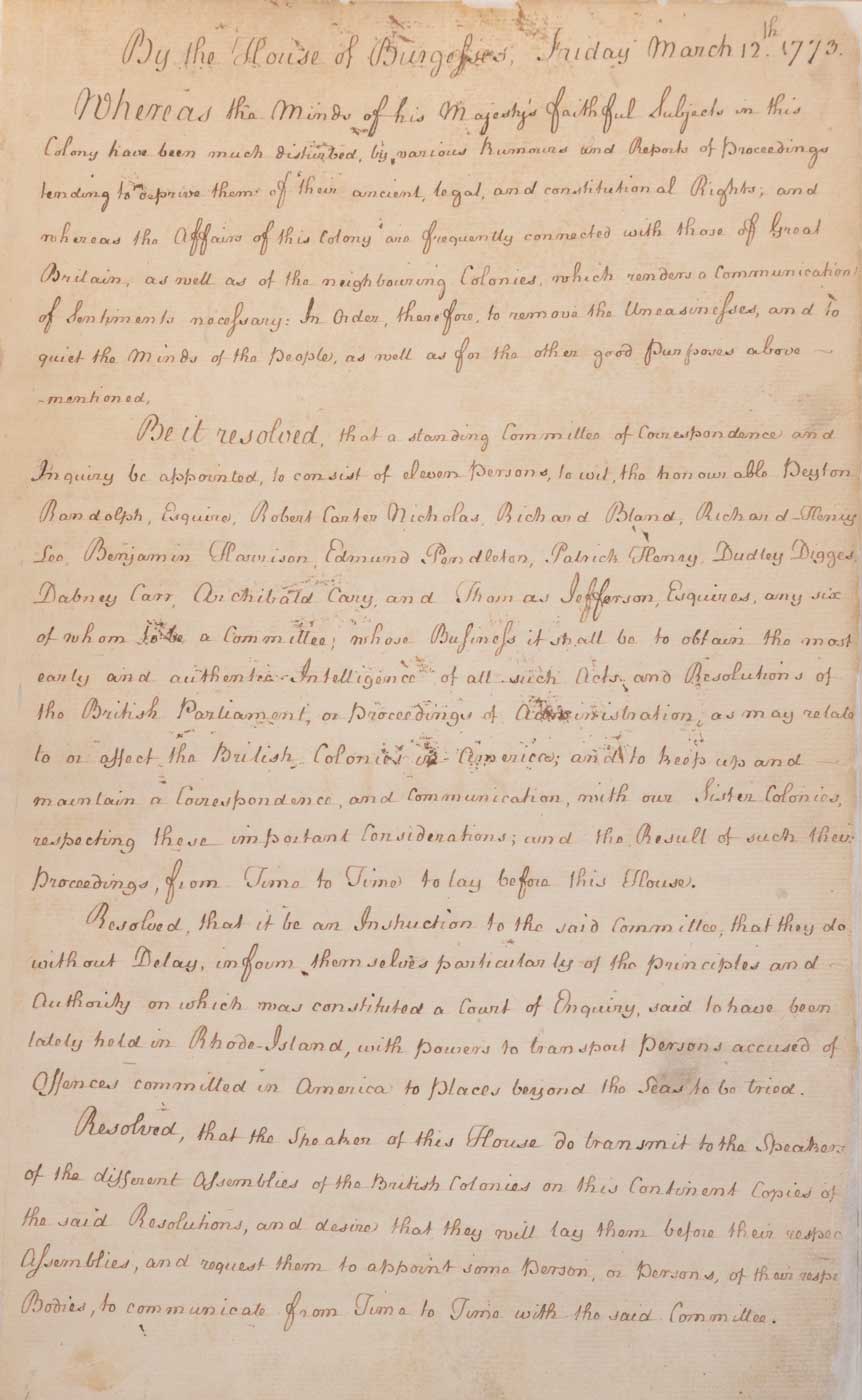

Virginia Adopts Committees of Correspondence Resolution

March 12, 1773

Thomas Jefferson’s friend and brother-in-law, Dabney Carr, presents the Raleigh Tavern gathering’s resolution on committees of correspondence to the Virginia House of Burgesses. The House accepts and adopts the resolution. It also sends copies of this resolution to the assemblies of the other twelve mainland colonies for consideration.

The Tea Act of 1773 Resolution

May 10, 1773

To assist the financially troubled English East India Company, Parliament passes the Tea Act of 1773. The act allows the East India Company to undercut the price of smuggled Dutch tea by permitting the company's ships to sail from East Asia directly to the colonies, bypassing the need to pay an additional excise tax. The act also limits who can sell tea in the colonies. Colonists up and down the Eastern Seaboard protest this tax, which makes tea cheaper to purchase but also sets a precedent for further parliamentary taxation.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

In this episode of the Doing History: To the Revolution series, Jane Merritt, Jennifer Anderson, and David Shields take us on an exploration of the politics of tea during the era of the American Revolution.

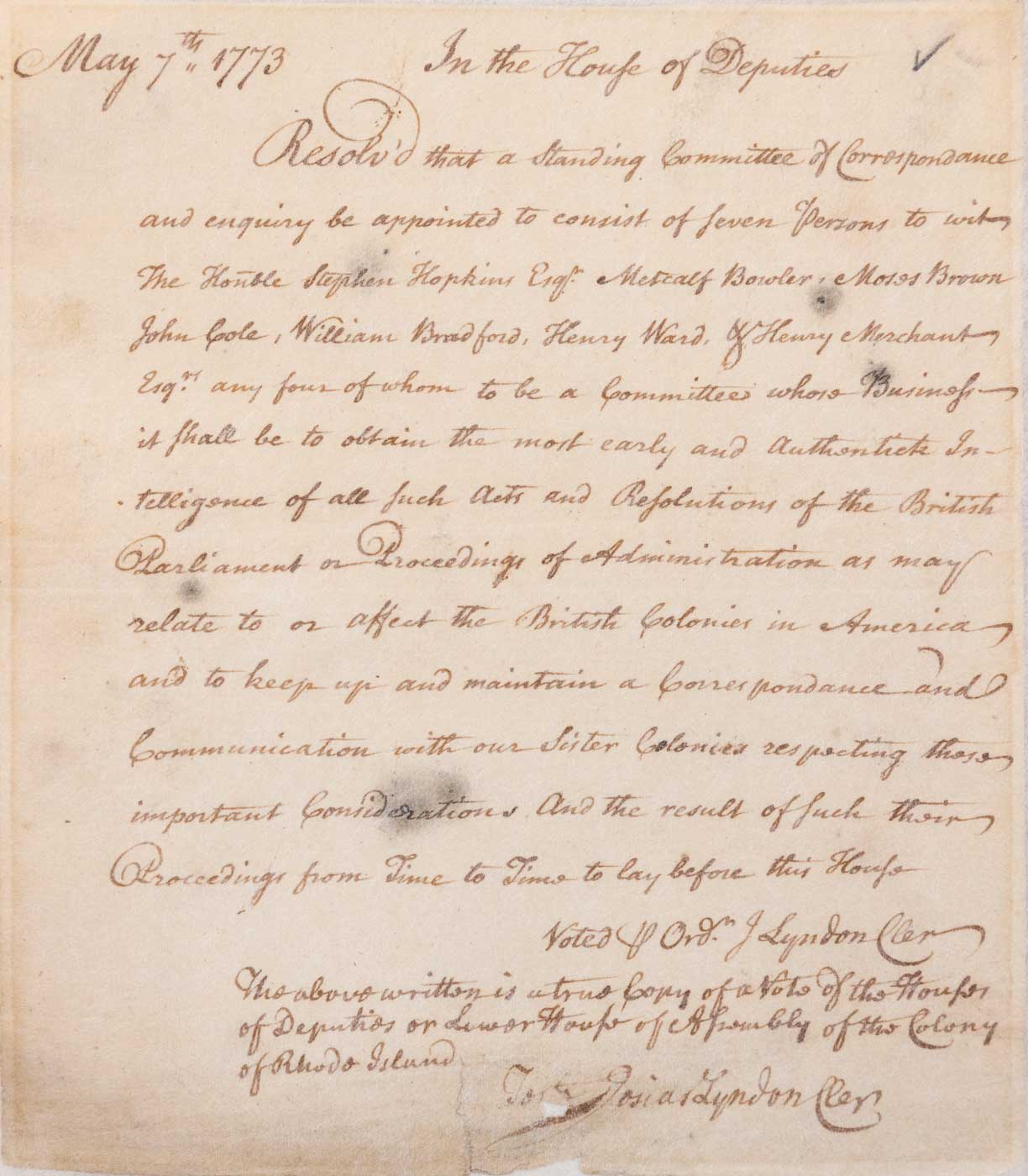

Rhode Island Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

May 15, 1773

Rhode Island becomes the first colony to discuss and adopt the Virginia resolution and form the recommended committee of correspondence.

Connecticut Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

May 21, 1773

Connecticut becomes the second colony to adopt the Virginia resolution and form a committee of correspondence.

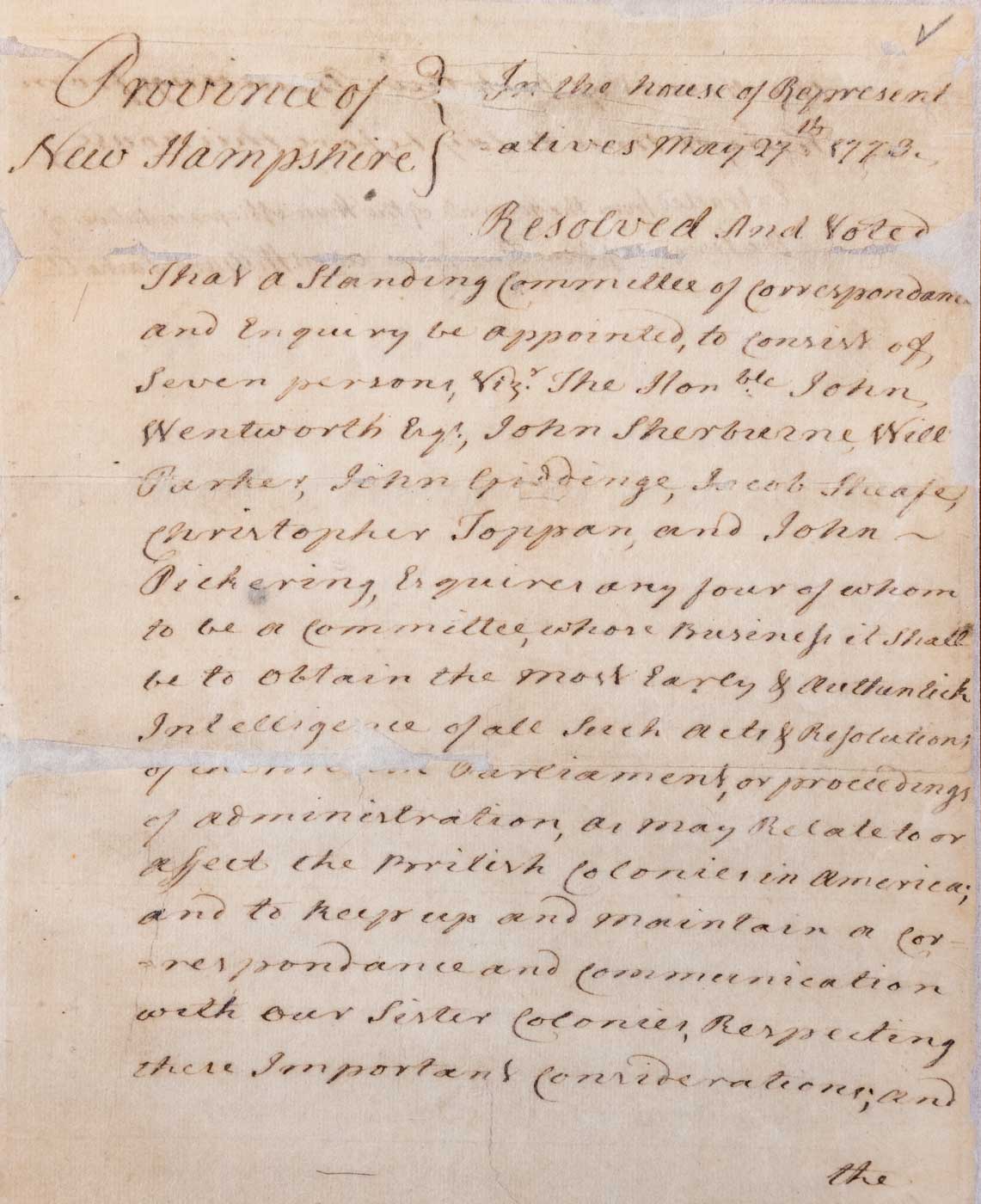

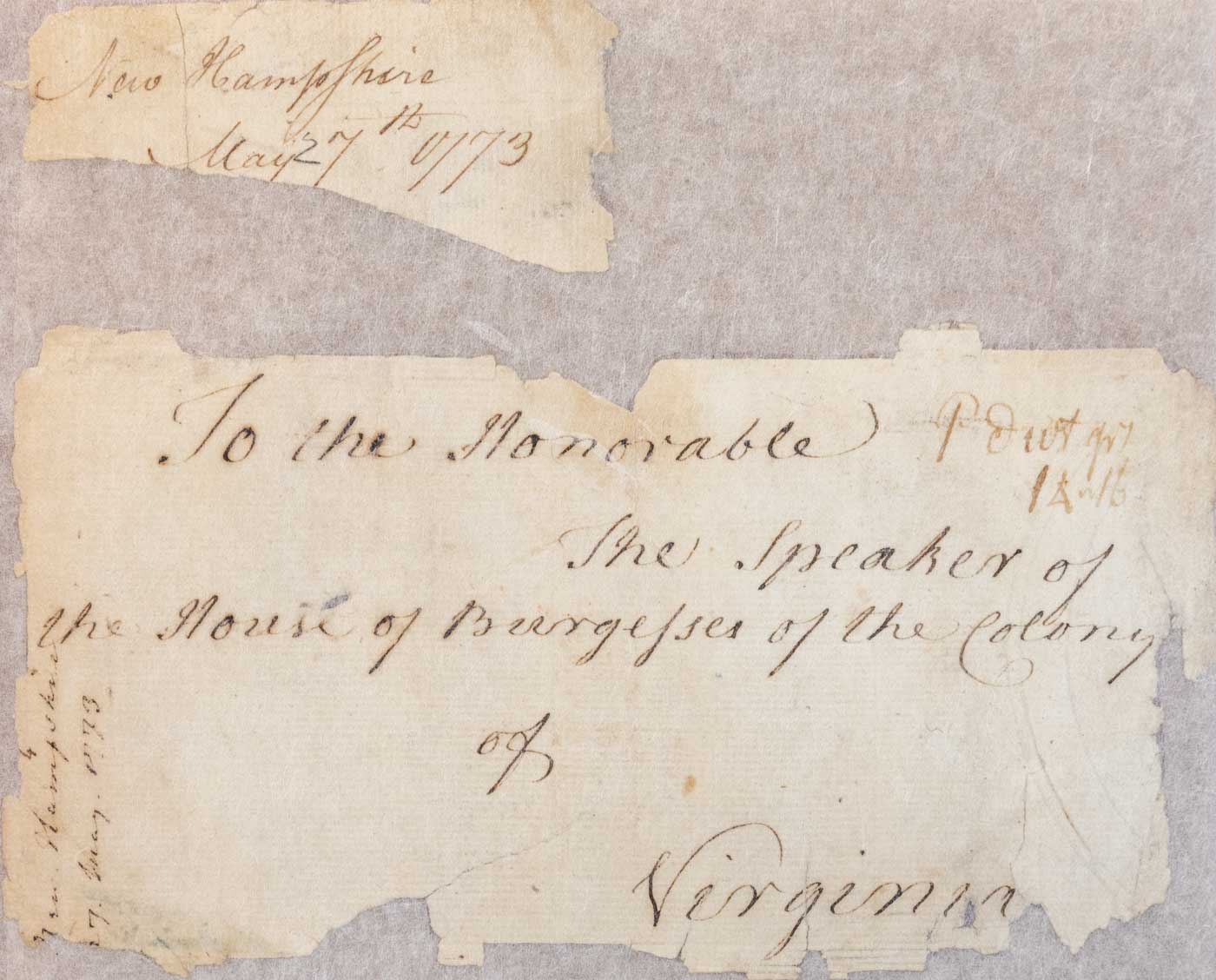

New Hampshire Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

May 27, 1773

New Hampshire becomes the third colony to form a committee of correspondence at Virginia’s suggestion.

Massachusetts Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

May 28, 1773

While Massachusetts towns formed committees of correspondence at the behest of the Boston Committee of Correspondence in November 1772, the colony did not have a committee to represent it as a whole. Following the lead of Virginia, the Massachusetts General Assembly becomes the fifth to form a committee of correspondence.

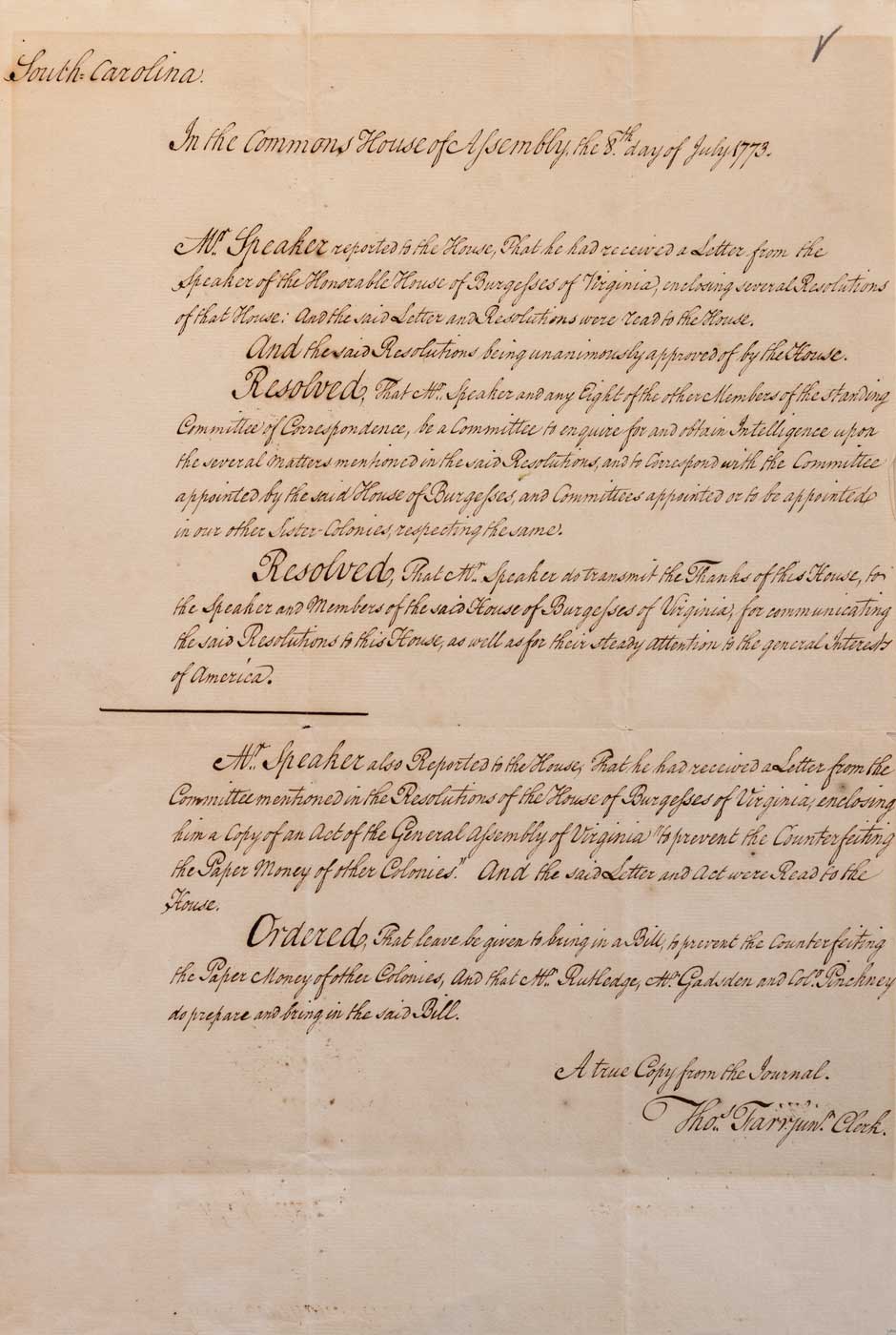

South Carolina Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

July 8, 1773

South Carolina becomes the sixth colony to adopt the Virginia resolution and form a committee of correspondence.

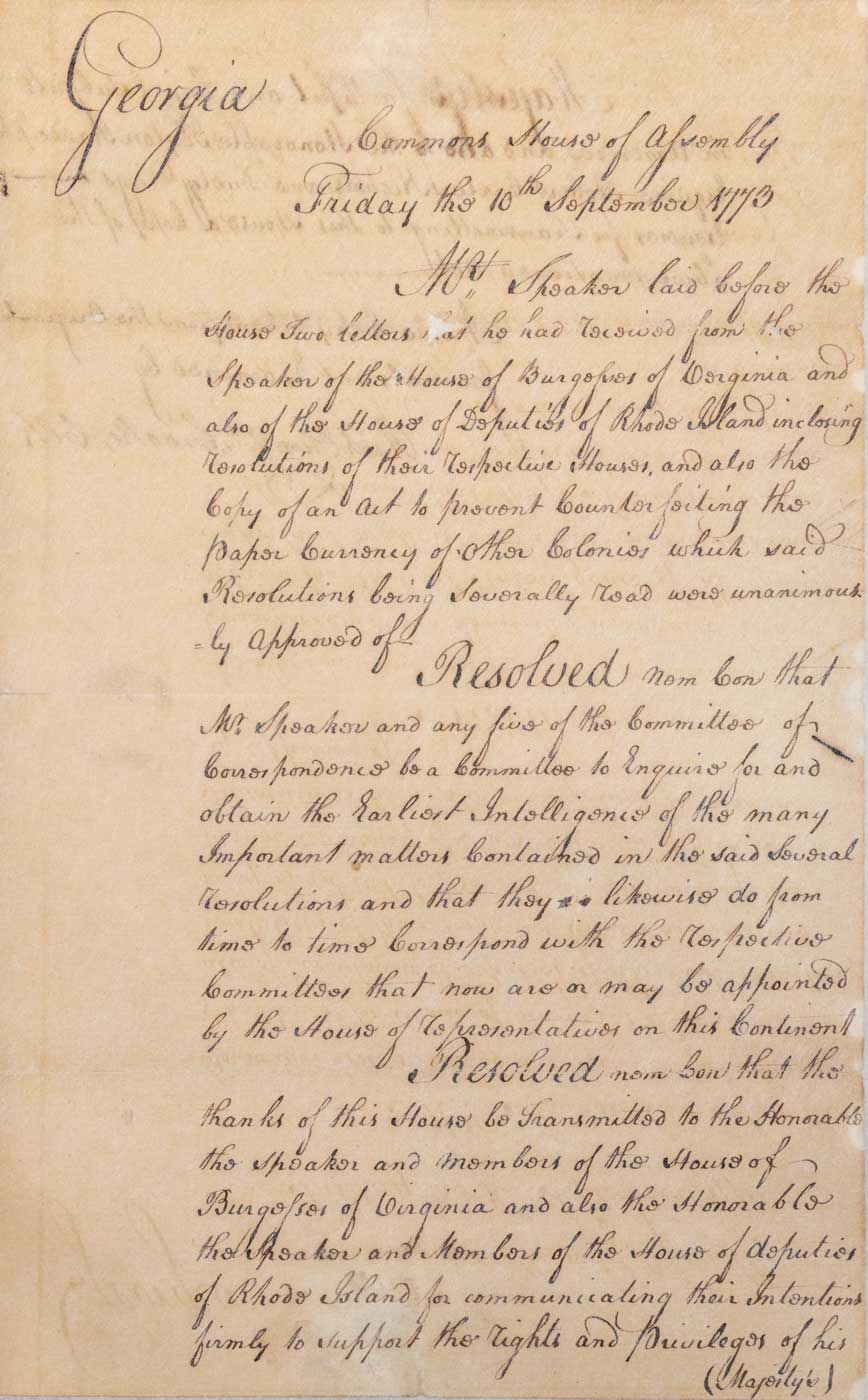

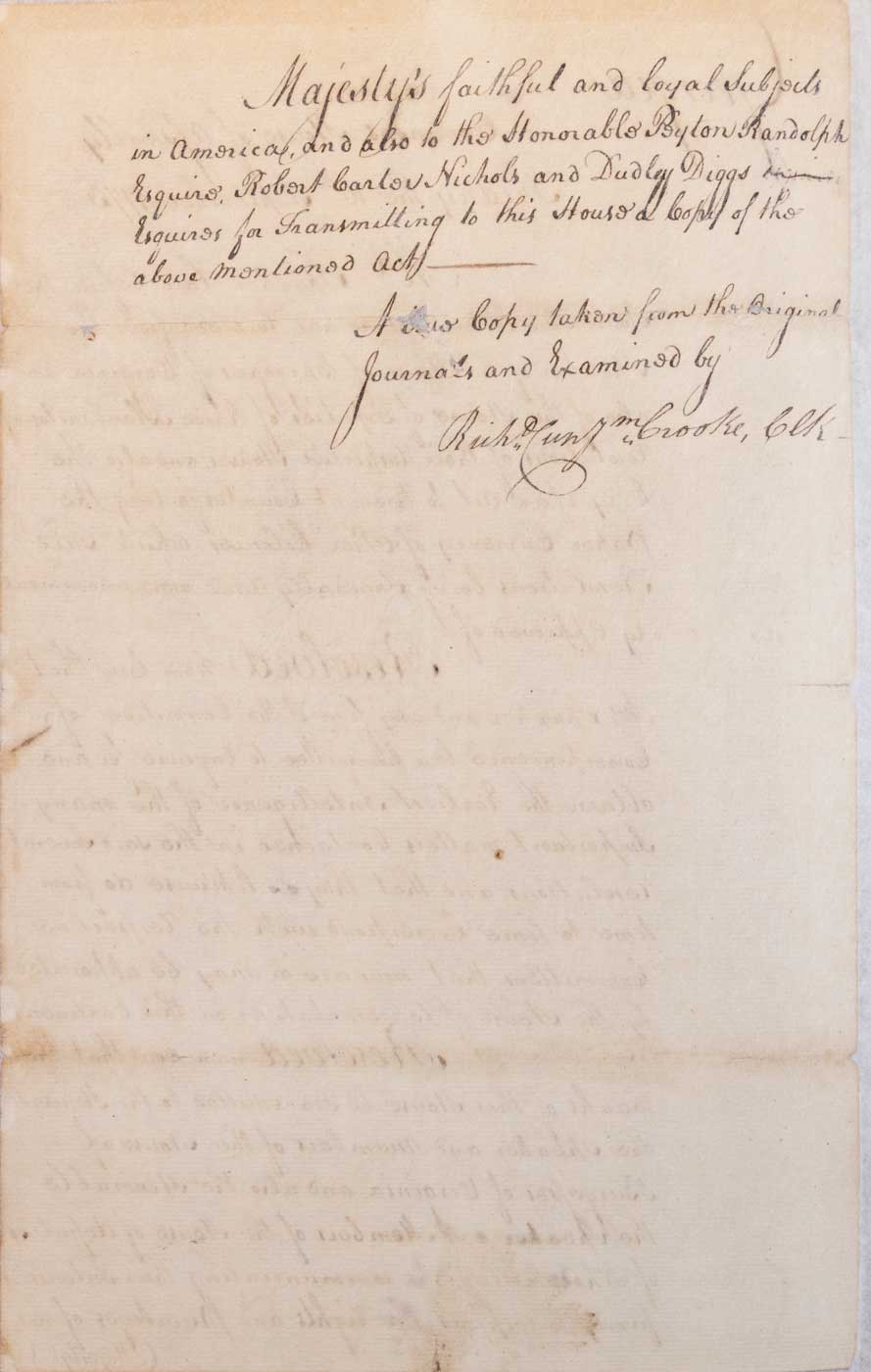

Georgia Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

September 10, 1773

Georgia follows Virginia’s advice and becomes the seventh colony to form a committee of correspondence.

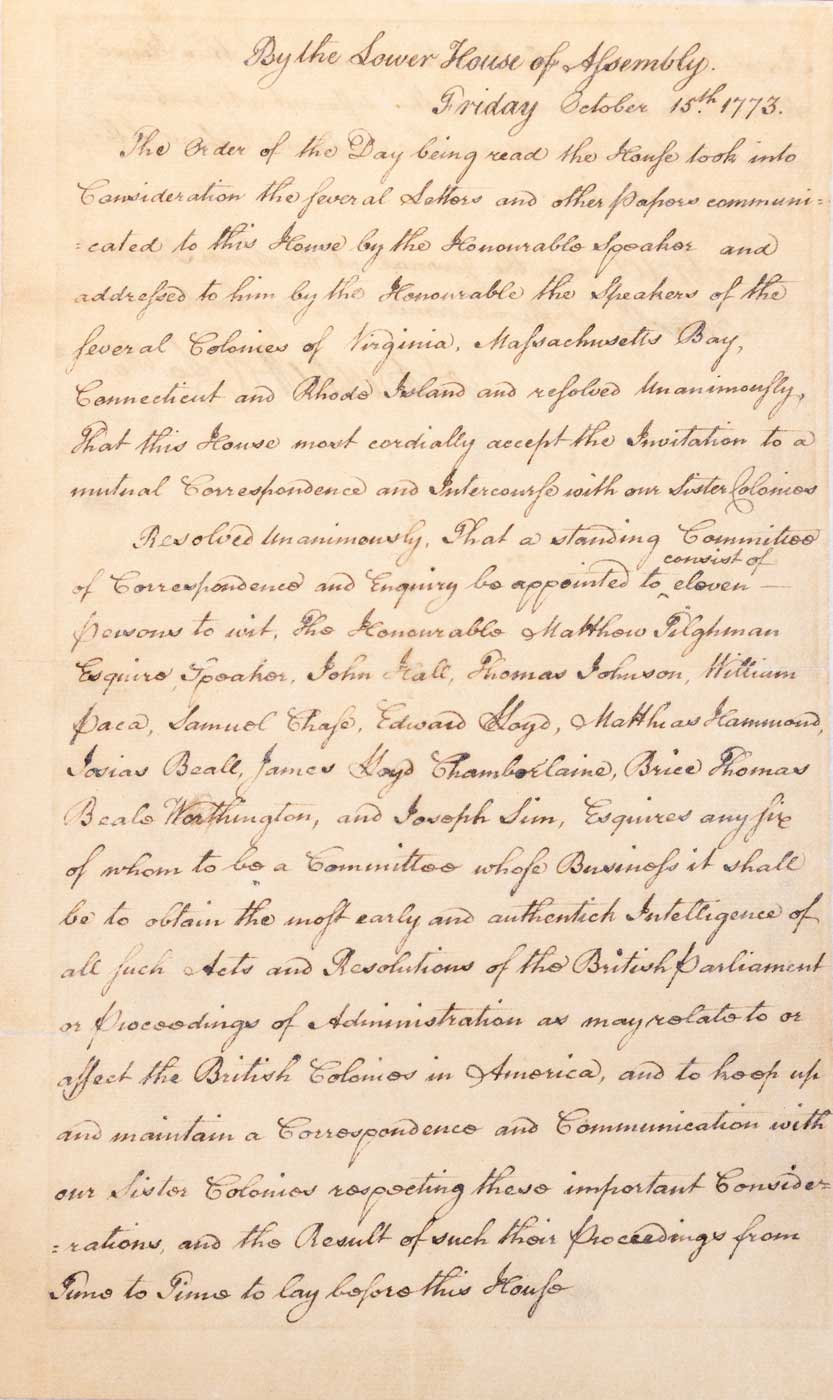

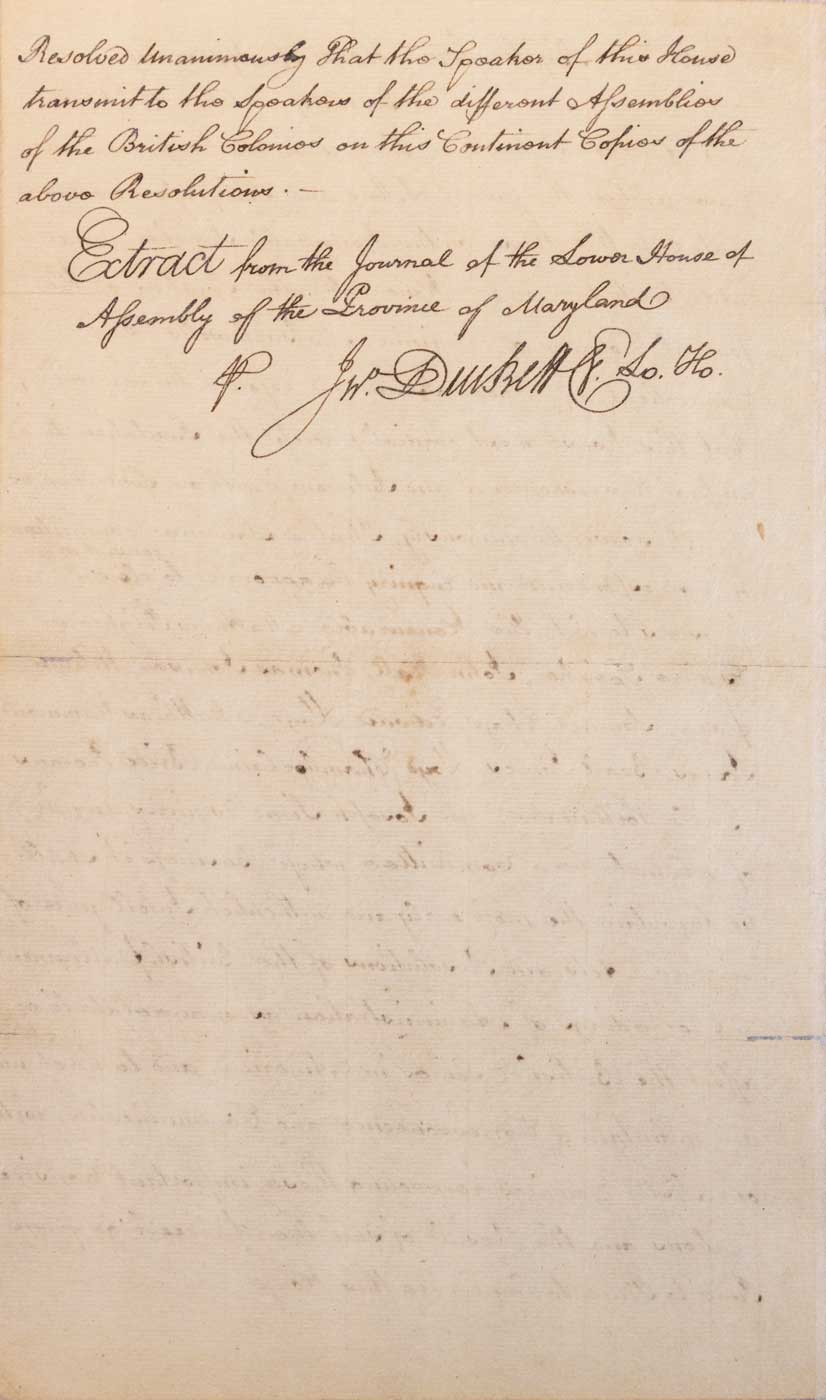

Maryland Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

October 15, 1773

Maryland becomes the eighth colony to create a committee of correspondence.

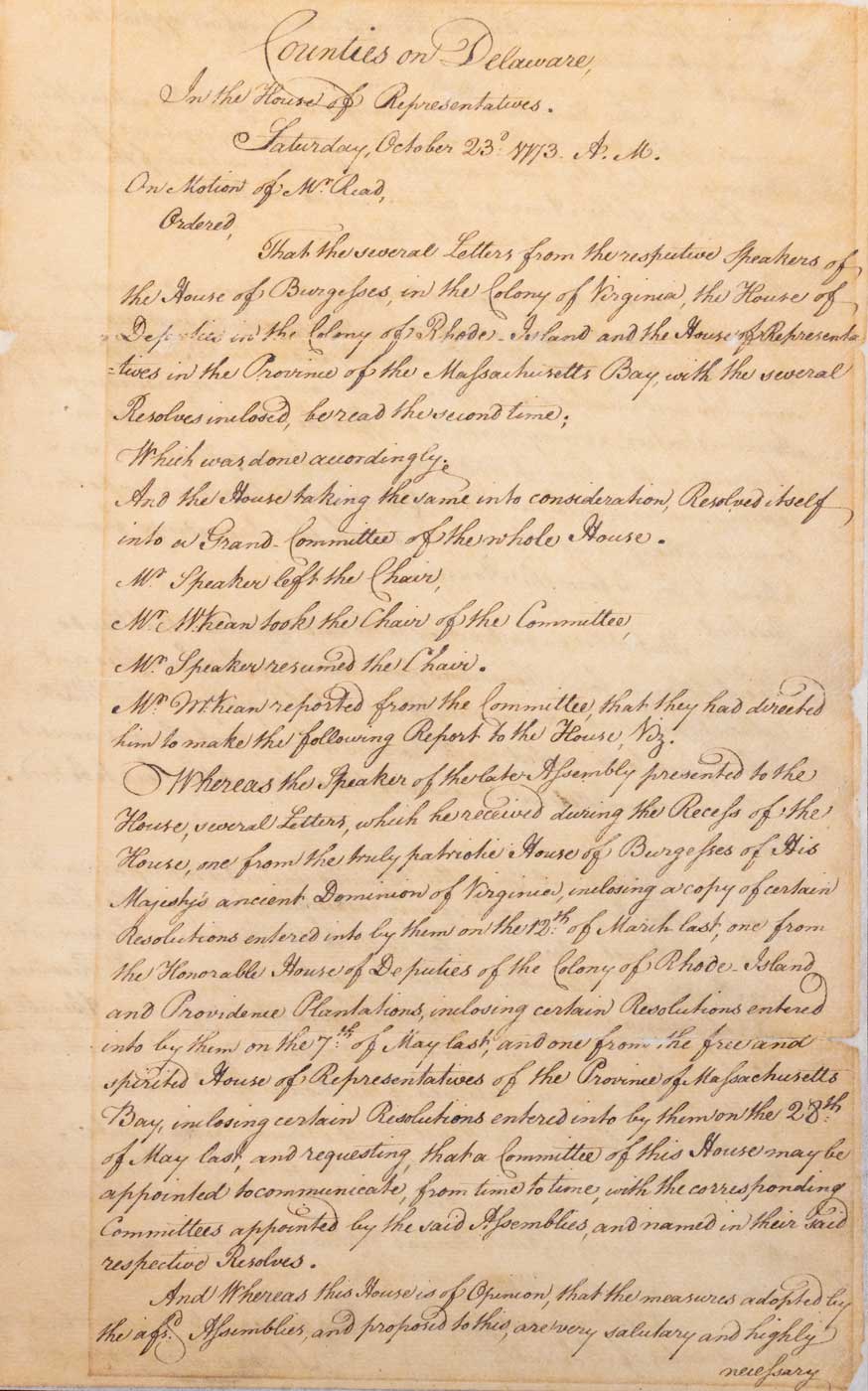

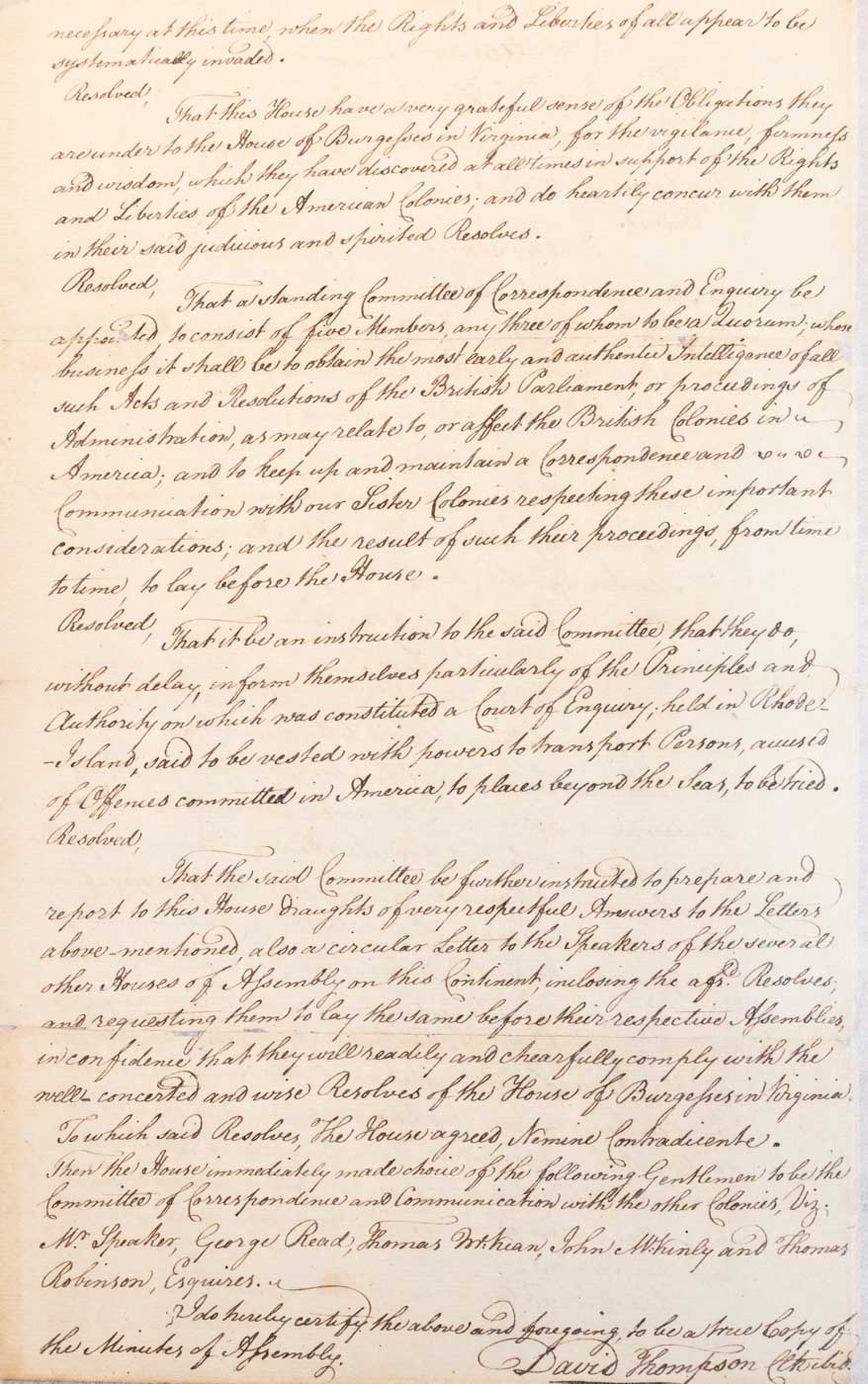

Delaware Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

October 23, 1773

Delaware debates and adopts the Virginia resolution as the ninth colony to create a committee of correspondence.

Boston Tea Party

December 16, 1773

Unable to convince Governor Thomas Hutchinson to send away the three tea-laden ships in Boston Harbor, nearly 5,000 Bostonians meet in the Old South Meeting House and agree to act. A group of men march down to Griffin’s Wharf under cover of darkness and loosely disguised as “Mohawk Indians,” board the three ships, and throw 342 chests of East India Company tea into Boston Harbor. Sometime in the nineteenth century, this act of protest becomes known as the “Boston Tea Party.”

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Mary Beth Norton, the Mary Donlon Alger Professor Emerita of American History at Cornell University, takes us through the Tea Crisis of 1773.

Listen to the Ben Franklin’s World podcast

Award-winning historian Mary Beth Norton, the Mary Donlan Alger Professor Emerita at Cornell University and the author of 1774: The Long Year of Revolution, joins us to discuss another year that she would like us to pay attention to as we think about the American Revolution: the year 1774.

North Carolina Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

December 18, 1773

North Carolina becomes the tenth colony to form a committee of correspondence.

Continental Congress Afoot

Revolutionaries begin the year 1774 with an organized, formal system of communication: the Committees of Correspondence. As 1774 inches toward 1775, the first year of war, more colonies join this network. Once parliament passes Coercive Acts in 1774, the rebellious colonies move to establish the First Continental Congress.

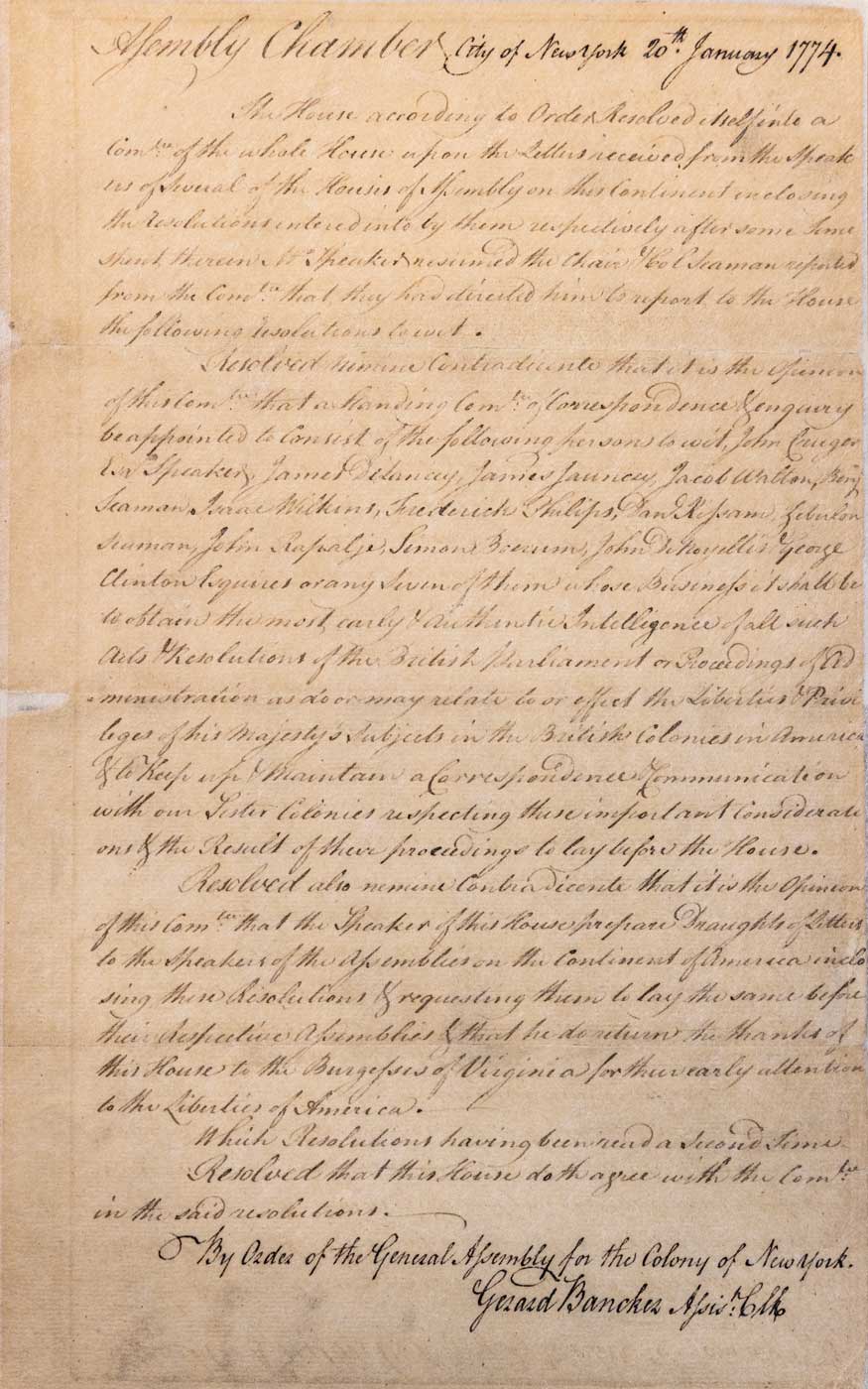

New York Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

January 20, 1774

New York becomes the eleventh colony to form a committee of correspondence.

New Jersey Appoints a Committee of Correspondence

February 8, 1774

The New Jersey Assembly authorizes the formation of the twelfth and final committee of correspondence. Neighboring Pennsylvania chooses not to form a committee.

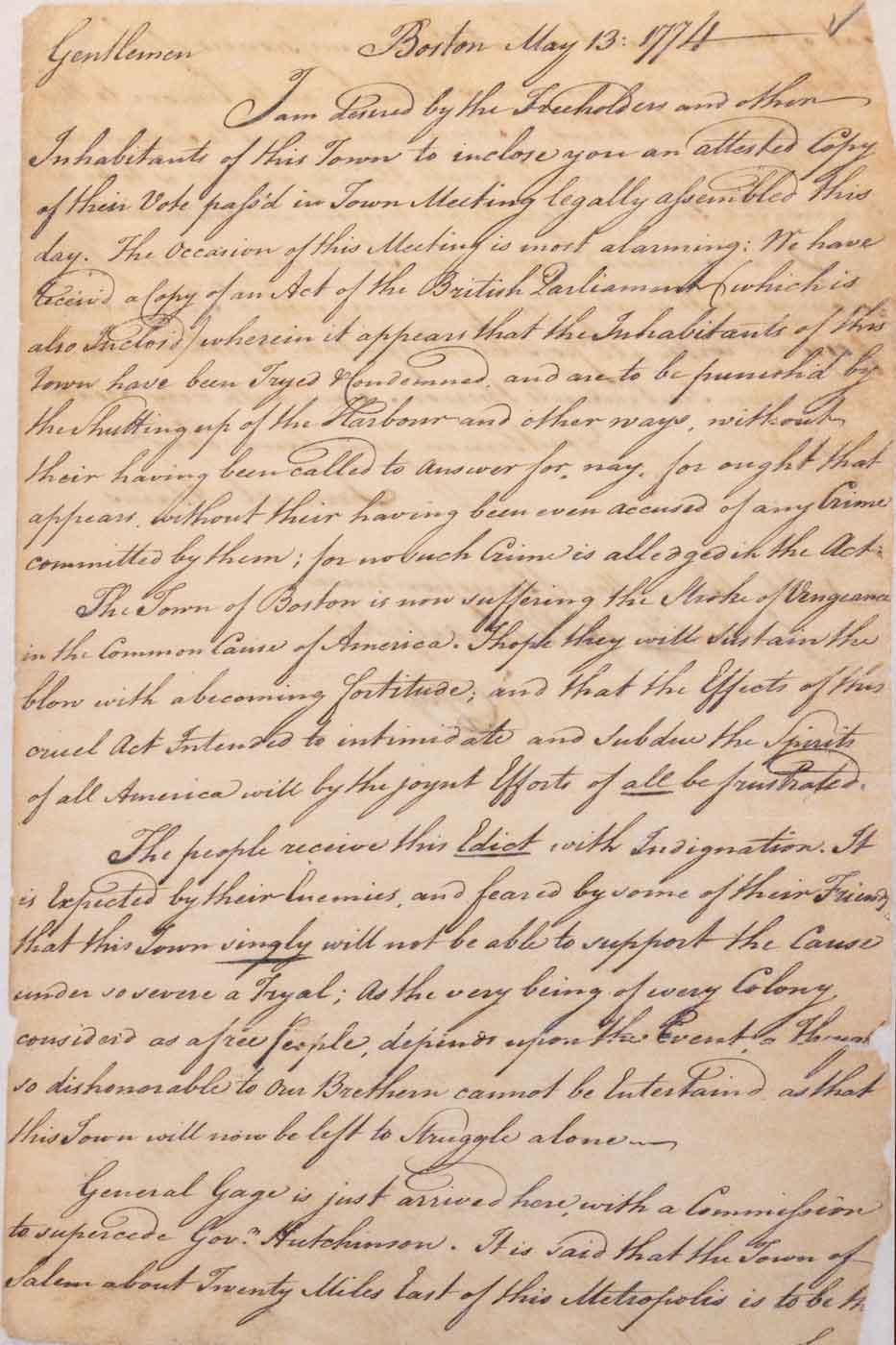

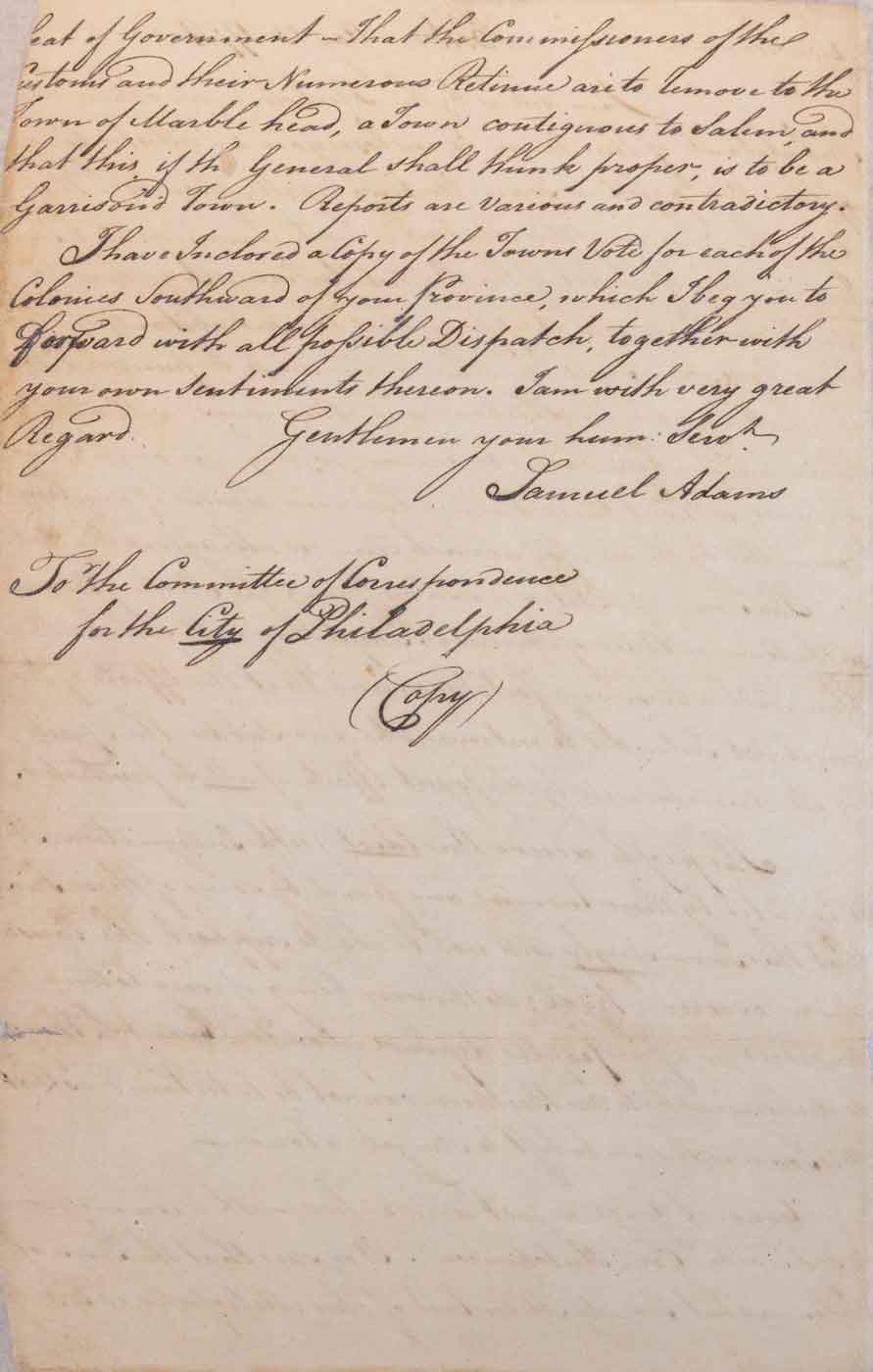

The Coercive Acts, Boston Port Act

March 31, 1774

Parliament meets and passes the Boston Port Act. This act comprises the first of four acts Parliament passes as part of the “Coercive Acts.” Colonists refer to these acts as the “Intolerable Acts.” The Boston Port Act enacts a naval blockade of Boston Harbor, blocking sea trade from entering or leaving the city until the colony remits the taxes and cost of the destroyed tea. The other Coercive Acts include the Massachusetts Government Act, which threatens representative government in Massachusetts (and sets a precedent to end it elsewhere); The Administration of Justice Act, which allows the Massachusetts governor to move trials for certain crimes to another colony or to England (threatening colonists’ right to a fair trial by their peers; and the Quartering Act. Unlike the other acts, which apply only to Massachusetts, the Quartering Act applies to all of the British American colonies. It requires colonial towns to allow the British military to quarter its men in vacant houses and public buildings in the absence of barracks.

New York Suggests a Continental Congress

May 23, 1774

New York City’s revolutionary Committee of Fifty-One writes to the Boston Committee of Correspondence and expresses a desire to invite “our sister colonies” to meet as “a congress of deputies” to discuss thoughts and actions as the imperial crisis grows.

Massachusetts and Virginia Call for a Continental Congress

May through June 1774

Independently of each other, the colonial assemblies of Massachusetts and Virginia propose an intercolonial gathering to discuss the growing imperial crisis. They propose that this “continental congress” meet in Philadelphia in September 1774.

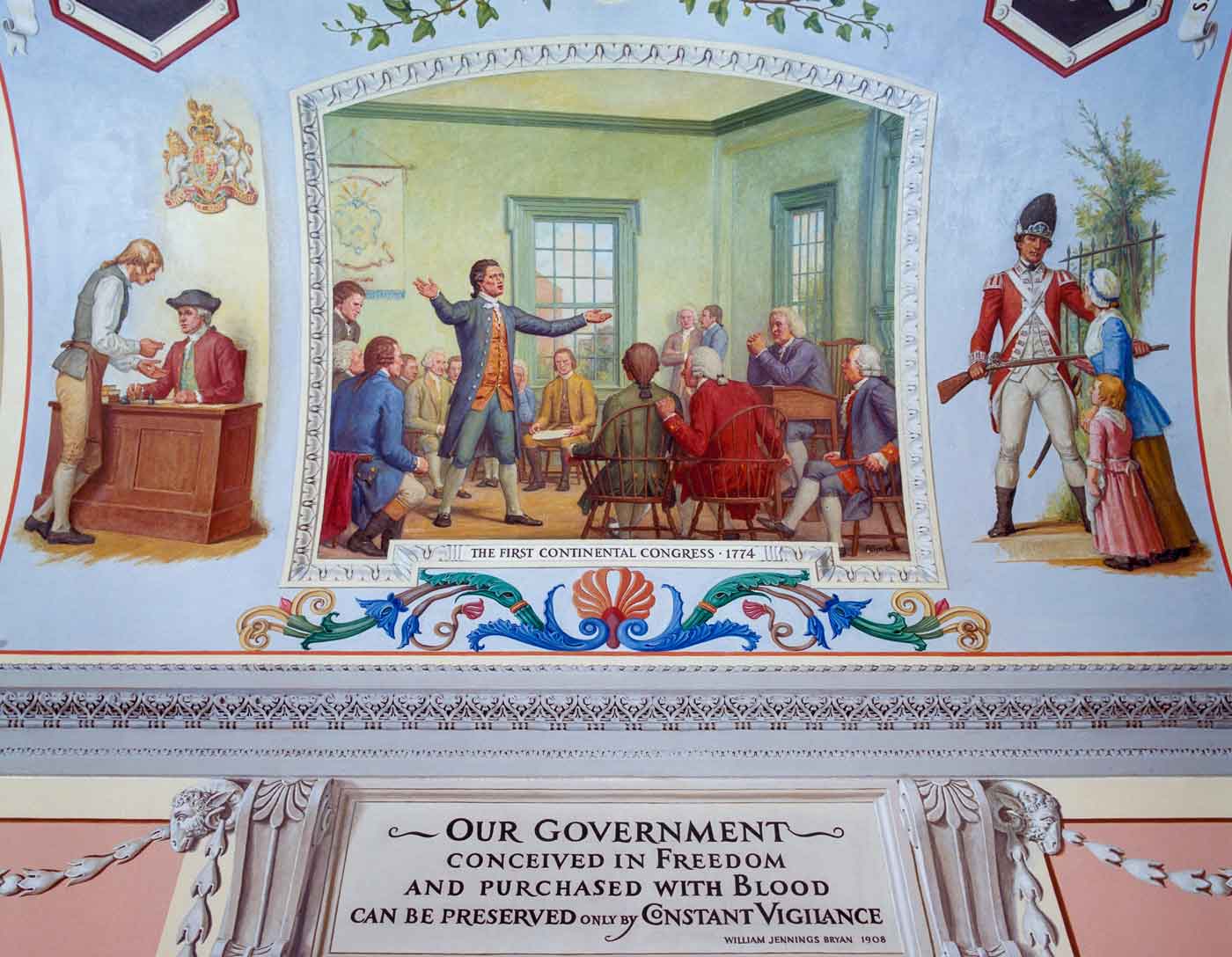

First Continental Congress Meets in Philadelphia

September 5–October 26, 1774

Delegates from twelve of the thirteen mainland colonies (Georgia excepted) meet in Philadelphia’s Carpenters’ Hall to discuss the imperial crisis and coordinate a plan of action.

The Suffolk Resolves

September 9, 1774

Leaders from Suffolk County, Massachusetts (the county that includes Boston) meet and draft a statement condemning the Massachusetts Government Act. Massachusetts leaders call upon the different colonies to insist on the repeal of the Massachusetts Government Act and the Boston Port Act by refusing to pay taxes and organizing a nonimportation/nonexportation movement. These Bay Colonists believe that the economic pressure could force the repeal of the Intolerable Acts just as an earlier nonimportation/nonexportation movement forced the repeal of the Townshend Duties in 1770. The Suffolk Resolves also include a resolve urging the other colonies to raise militias in preparation for war. The Suffolk committee dispatches these resolves to Philadelphia under the care of Paul Revere.

First Continental Congress Adopts the Suffolk Resolves

September 17, 1774

The First Continental Congress endorses the Suffolk Resolves and advises the colonies to adopt their provisions

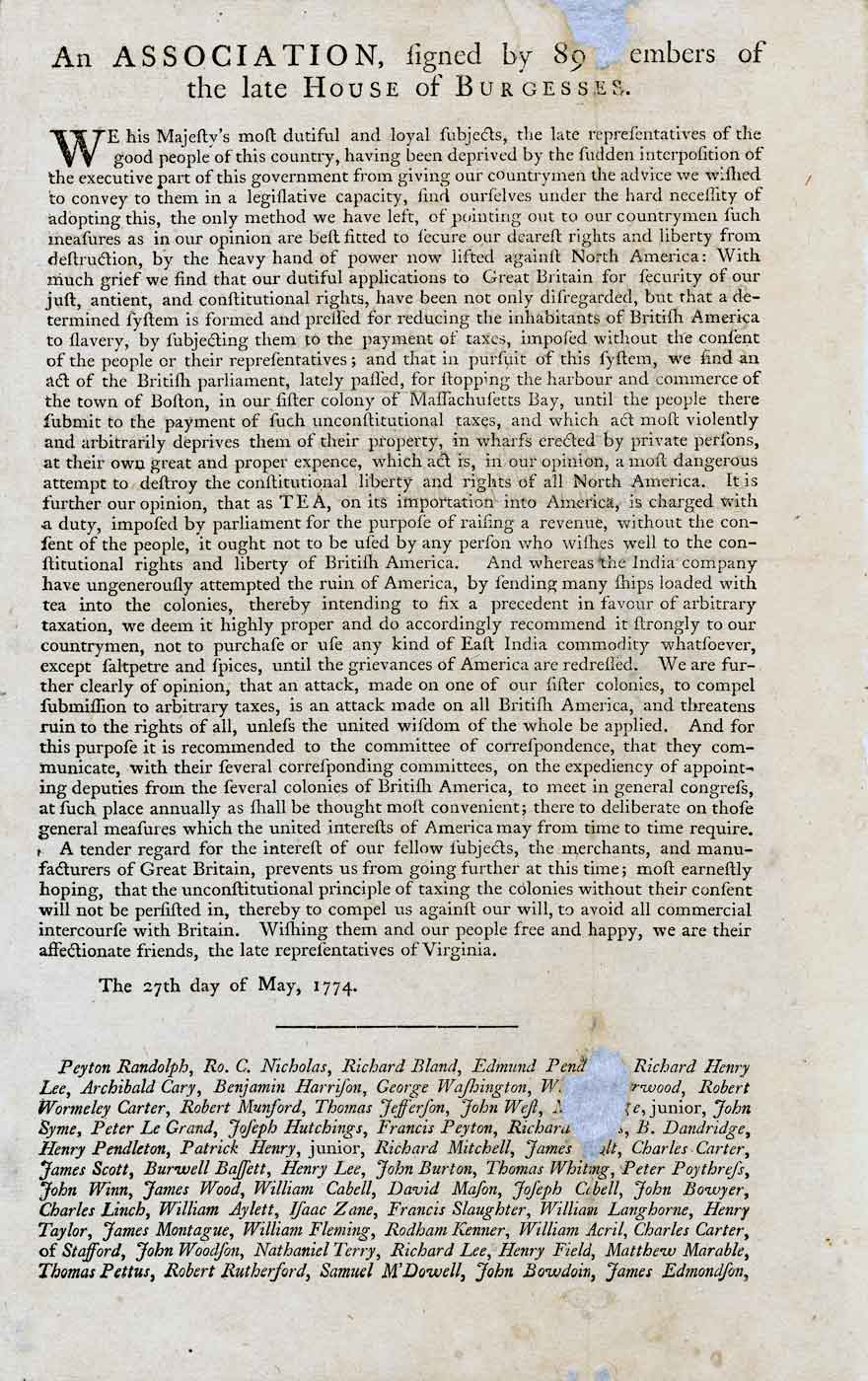

First Continental Congress Adopts Continental Association

October 20, 1774

The First Continental Congress devises the Continental Association, an agreement between the colonies to participate in a nonimportation/nonexportation movement. The Association includes fourteen articles of association. The eleventh article advises each city, town, and county to elect members to committees that will enforce this intercolonial nonimportation agreement. The twelfth article encourages these newly formed committees to inspect local custom house registers to learn about and report any violations of the agreement. This system of local committees quickly gives way to a more formal system of revolutionary government composed of provincial congresses (to replace colonial assemblies) and local committees of safety (to replace local governments) that monitor and enforce revolutionary laws and behavior.

The intercolonial Committees of Correspondence were established in 1773 as information gathering and disseminating bodies. By 1774, they had established collective oppositional responses to British policies that were formalized in the First Continental Congress. In February 1775, Massachusetts would be declared in open rebellion against the Royal Authority, and so a second congress would be convened, this time acting essentially as a unified government to fight for American Independence.

Reflections on Committees of Correspondence

Founding Director of Colonial Williamsburg's Innovation Studios, Liz Covart, Ph.D., sits down with Patrick Henry as he reflects on the rebellious act that would fuel a revolution.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- John Adams to Jedidiah Morse[TI1] , December 22, 1815, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6558.

- Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congresses, 1774–1789, vol. 1, 1774, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904).

- Continental Association, October 20, 1774, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0094.

- Samuel Cooper to Benjamin Franklin, June 14[–15], 1773, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0136.

- Thomas Cushing to Benjamin Franklin, April 20, 1773, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-20-02-0100.

- Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on Early Career (the so-called ‘Autobiography’),” in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, ed. James P. McClure and J. Jefferson Looney (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008–2023) https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/TSJN-03-17-02-0324-0002.

- William J. Van Schreeven and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 1, Forming Thunderclouds and the First Convention, 1763–1774 (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1973).

- William J. Van Schreeven and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 2, The Committees and the Second Convention, 1773–1775 (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1975).

Secondary Sources

- Richard D. Brown, Revolutionary Politics in Massachusetts: The Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Towns, 1772–1774 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970).

- Edward D. Collins, “Committees of Correspondence of the American Revolution,” in Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1901, vol. 1, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1901), 243–72.

- Eric Hinderaker, Boston’s Massacre (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2017).

- Mitch Kachun, First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- E. I. Miller, “The Virginia Committee of Correspondence, 1759–1770,” William and Mary Quarterly 22, no. 1 (July 1913): 1–19.

- E. I. Miller, “The Virginia Committee of Correspondence of 1773–1775,” William and Mary Quarterly 22, no. 2 (October 1913): 99–113.

- Mary Beth Norton, 1774: The Long Year of Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020).

- Mary Beth Norton, “The Seventh Tea Ship,” William and Mary Quarterly 73, no. 4 (October 2016): 681–710.

- John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775–1783,(Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988).

Further Reading

Trend & Tradition

- Cathy Hellier, “Acting Up: Williamsburg was not resigned to the imposition of the Stamp Act,” Spring 2020

- Jon Kukla, “Fatal Infatuation: Prime Minister George Grenville was in love with his Stamp Act plan — but the American colonies outsmarted him,” Spring 2020

- Parissa DJangi, “An Ill Wind: The Gaspée Affair and its ominous aftermath contributed to a breaking point with Britain,” Summer 2022

Primary Sources from Our Collections

- A letter to the gentlemen of the committee of London merchants, trading to North America : shewing in what manner, it is apprehended, that the trade and manufactures of Britain may be affected by some late restrictions on the American commerce, and by the operation of the act for the stamp duty in America; as also how far the freedom and liberty of the subjects residing in Britain, are supposed to be interested in the preservation of the rights of the provinces, and in what manner those rights appear to be abridged by that statute. London : Printed for W. Richardson & L. Urquhart, booksellers, under the Royal Exchange, Cornhill, 1766., E211 .L493 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991012830199703196

- An answer to a pamphlet entitled Taxation no tyranny : Addressed to the author, and to persons in power. London : Printed for J. Almon, opposite Burlington House, Piccadilly, 1775., E211 .A57 1775, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991013844319703196

- Ames's almanack revived and improved: or, An astronomical diary, for the year of our Lord Christ 1766. ... Calculated for the meridian of Boston in New-England, lat. 42 deg. 25 min. north. ... Boston : Printed and sold by R. & S. Draper, in Newbury-Street, south-end … 1765., AY53 .A54 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991010948549703196

- Appleton, Nathaniel. The Right Method of Addressing the Divine Majesty in Prayer : so as to Support and Strengthen Our Faith in Dark and Troublesome Times : Set Forth in Two Discourses on April 5, 1770 : Being the Day of General Fasting and Prayer through the Province : and in the Time of the Session of the General Court at Cambridge. Boston: Printed by Edes and Gill, Printers to the Honorable House of Representatives, 1770. Print,https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991011157409703196

- Authentic account of the proceedings of the Congress held at New-York, in MDCCLXV, on the subject of the American Stamp Act. [London : Printed for John Almon], 1767., E215.2 .S73 1767, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991011155839703196

- The charters of the following provinces of North America : viz. Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Massachusett's Bay, and Georgia : To which is prefixed, a faithful narrative of the proceedings of the North American colonies, in consequence of the late Stamp-Act. London : Printed for W. Owen, J. Almon, and F. Blyth at John's Coffee-house, Royal-Exchange, 1766, E215.2.C48 1766

- Continental Congress. Extracts from the votes and proceedings of the American Continental Congress : held at Philadelphia on the 5th day of September, 1774. Containing, the Bill of Rights, a list of grievances, occasional resolves, the association, an address to the people of Great Britain, and a memorial to the inhabitants of the British American colonies. Philadelphia : Printed by William and Thomas Bradford, 1774, KF35.E98 1774, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991031868879703196

- Dulany, Daniel. Considerations on the propriety of imposing taxes in the British colonies, for the purpose of raising a revenue, by act of Parliament ... London : Re-printed for J. Almon …, 1766., E211 .D876, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/1r1dku9/alma991024799469703196

- The Examination of Doctor Benjamin Franklin, before an August assembly, relating to the repeal of the Stamp-Act, &c., E215.2 .G74,https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991025257769703196

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Lords. Second protest with a list of the voters against the bill to repeal the American Stamp Act, of last session. A Paris i.e. London : Chez J. W. imprimeur, rue du Colombier, Fauxbourg St. Germain, à l'hotel de Saxe, 1766., E215.2.G745 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991032224999703196

- Hopkins, Stephen. The grievances of the American colonies candidly examined. London : Reprinted for J. Almon, opposite Burlington-House, in Picadilly, 1766, E215.2 .H66 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/1r1dku9/alma991008764379703196

- Jefferson, Thomas. A Summary view of the rights of British America : set forth in some resolutions intended for the inspection of the present delegates of the people of Virginia, now in convention... Williamsburg : Printed by Clementina Rind ; London : Re-printed for G. Kearsly, 1774., E211 .J44 1774, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991024655809703196

- Jenyns, Soame. The objections to the taxation of our American colonies, by the legislature of Great Britain, briefly consider'd. London : printed for J. Wilkie, in St. Paul's Church Yard, 1765, E215.5 .J46 1765, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991007127669703196

- Johnson, Samuel. Taxation no tyranny; an answer to the resolutions and address of the American Congress. London : Printed for T. Cadell, 1775., AC901 .M5, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991024804159703196

- Knox, William. The controversy between Great Britain and her colonies reviewed : the several pleas of the colonies, in support of their right to all the liberties and privileges of British subjects, and to exemption from the legislative authority of Parliament, stated and considered; and the nature of their connection with, and dependence on, Great Britain, shewn, upon the evidence of historical facts and authentic records. London : Printed for J. Almon, opposite Burlington-House, in Piccadilly, 1769., E211.K58 1769, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991005293579703196

- Lee, Arthur. The political detection; or, The treachery and tyranny of administration, both at home and abroad; displayed in a series of letters, signed Junius Americanus. London : Printed and sold by J. and W. Oliver ..., 1770., E211 .L475 1770, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991032225009703196

- Lloyd, Charles. The Conduct of the late administration examined, relative to the American stamp-act : with an appendix, containing original and authentic documents. London : Printed for J. Almon ..., [1767], E215.2 .L56 1767, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991023354819703196

- Mayhew, Jonathan. The snare broken : A thanksgiving-discourse. Boston : Printed and Sold by R. & S. Draper, in Newbury-Street; Edes & Gill, in Queen-Street; and T. & J. Fleet, in Cornhill, 1766, E215.2 .M39 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991012324299703196

- The Necessity of repealing the American Stamp-Act demonstrated : or, A proof that Great-Britain must be injured by that act. In a letter to a member of the British House of Commons. London : Printed for J. Almon, opposite Burlington-House, Piccadilly, 1766, E215.2.N43 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991005063539703196

- Pitt, William. The speech of Mr. P------- and others : in a certain august assembly on a late important debate: with an introduction of the matters preceding it. [London?] : Printed in the year [17]66, E215.2 .P58 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991001749889703196

- Rokeby, Matthew Robinson-Morris, Baron. Considerations on the measures carrying on with respect to the British colonies in North America. London : Printed for R. Baldwin, Pater-noster Row, E. and C. Dilly, in the Poultry, J. Johnson, St. Paul's Church-Yard, Richardson and Co. at the Royal Exchange, and J. Almon, Piccadilly, 1774., E211 .R648 1774b, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/1r1dku9/alma991013124129703196

- Rowland, David S.,Divine providence illustrated and improved : A thanksgiving-discourse, preached (by desire) in the Presbyterian, or Congregational church in Providence, N.E. Wednesday June 4, 1766, being His Majesty's birth day, and day of rejoicing, occasioned by the repeal of the Stamp-act ... Providence New-England : Printed by Sarah Goddard, and Company, 1766, E215.2 .R69 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991005132669703196

- Seabury, Samuel. The Congress canvassed : or, an examination into the conduct of the delegates, at their grand convention, held in Philadelphia, Sept. 1, 1774. Addressed, to the merchants of New-York. New York : Printed by James Rivington in the year 1774., E211.S424 1774, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991004282889703196

- Shipley, Jonathan. A speech intended to have been spoken on the bill for altering the charters of the colony of Massachusett's Bay. London : Printed for T. Cadell, in the Strand, 1774., E211 . S55 1774c, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/1r1dku9/alma991012589699703196

- Tucker, Josiah, A letter from a merchant in London to his nephew in North America, relative to the present posture of affairs in the colonies; in which The supposed Violation of Charters, and the several Grievances complained of, are particularly discussed, and the Consequences of an Attempt towards Independency set in a true Light. London : printed for J. Walter, at Homer's Head, Charing Cross, 1766, E211 .T853 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991008041239703196

- Tucker, Josiah, 1712-1799. A letter from a merchant in London to his nephew in North America, relative to the present posture of affairs in the colonies : in which the supposed violation of charters, and the several grievances complained of, are particularly discussed, and the consequences of an attempt towards independency set in a true light ... London : Printed for J. Walter, at Homer's Head, Charing Cross, MDCCLXVVI, E211 .T853 1766, https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991011311719703196

- Whately, Thomas. The regulations lately made concerning the colonies,and the taxes imposed upon them, considered. London : Printed for J. Wilkie, in St. Paul's Church-Yard, and may be had at the Pamphlet-Shops at the Royal-Exchange, and Charing-Cross, 1765., E215.2 .W47 1765,https://cwf.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01COWM_INST/a2dctr/alma991004864719703196

Resources from other Cultural Institutions