“We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” -Thomas Paine in Common Sense, January 1776

1776

In 1776, Americans fought a war and created an independent nation. When the Continental Congress declared independence in July 1776, it held “these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” With the Declaration of Independence, members of Congress created an independent nation based upon the “consent of the governed.”1 They began the world over again.

The Burning of Norfolk

A bustling port town, Norfolk was Virginia’s largest city in 1776. Many of its residents were merchants who sold tobacco and imported British-made goods. Because of their close economic relationship with Britain, many of them were also loyal to the British crown.

Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, had been living on a ship in Norfolk since fleeing Williamsburg in June 1775. With Patriots occupying Norfolk, Dunmore’s flotilla was cut off from supplies. In late December, the British forces threatened to bombard Norfolk in order to gain access to the city and its supplies, and followed through on January 1. Patriots added fuel to the fire, literally. They set fire to the city, in part to punish its Loyalists and in part to make Norfolk uninhabitable so the British could not occupy it. Norfolk was in ruins.2

Virginia’s governing body had ordered Patrick Henry, who commanded Virginia’s military forces, to remain in Williamsburg. He looked on helplessly as subordinates took command in Norfolk, and in February he resigned in frustration. Officers held a farewell dinner for him at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg.3

The year prior, British forces had leveled Falmouth, Maine, and Charlestown, Massachusetts. The destruction of American cities offered proof to many Americans that the King was willing to use to brutal force to suppress them.4

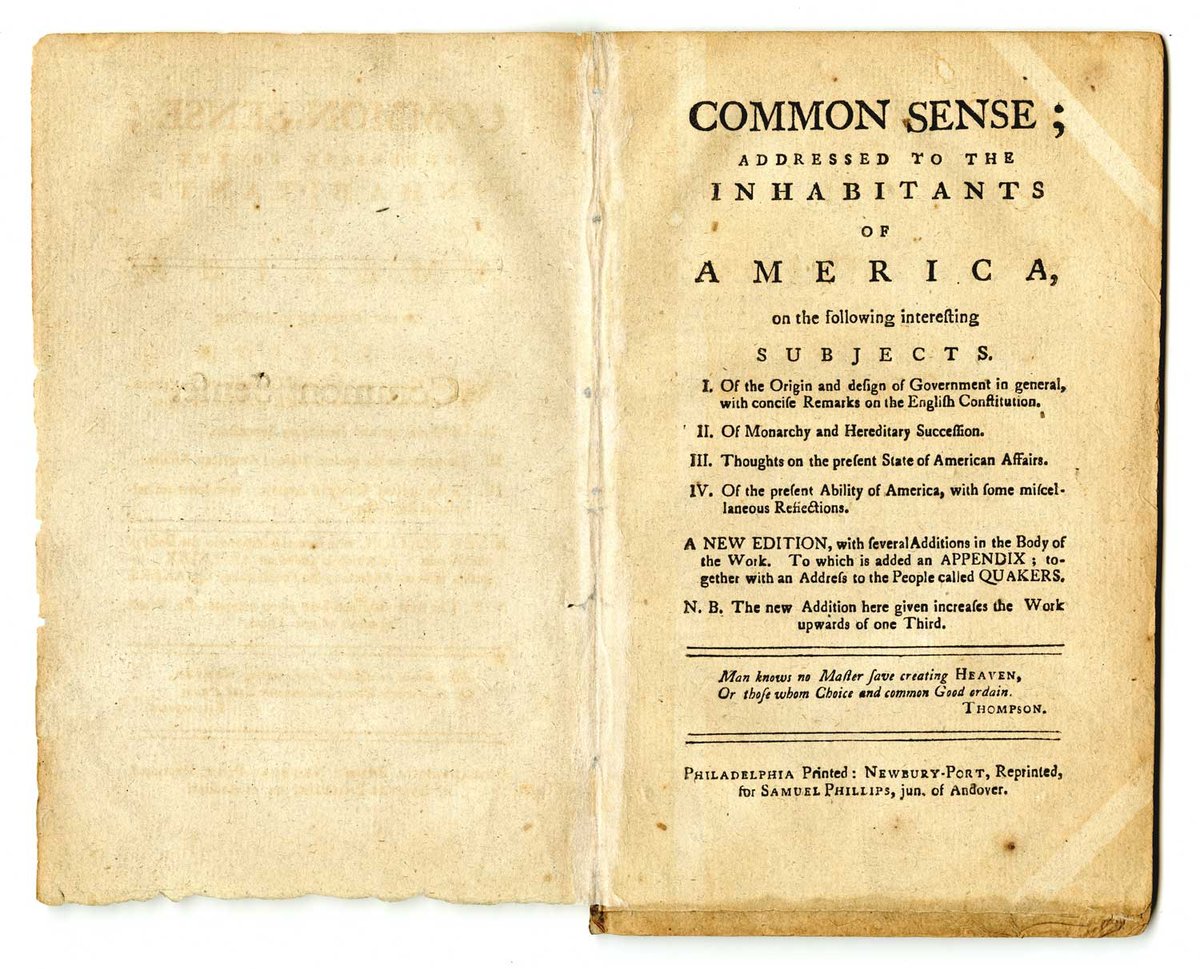

Common Sense Published

In early 1776, many American colonists hoped to reconcile with the crown, while others believed that the time had come to officially break off from Great Britain. A pamphlet published in early January would help shift the tide toward independence.

In Common Sense, Thomas Paine used plain yet forceful language to argue that independence was the only path forward. First printed in Philadelphia, the pamphlet went through 25 editions and spread throughout the colonies, although distribution was uneven.5

In Virginia, dissemination was inconsistent, and reviews were mixed. One of George Washington’s correspondents noted that “The opinion for independentcy seems to be gaining ground” as people read the pamphlet, while another attacked the pamphlet for being full of “art, and contradiction.” Thomas Jefferson recalled that its reach was far from universal, remembering that just extracts were printed in the newspaper in Williamsburg and the pamphlet had only “got in a few hands.”6 The Virginia Gazette did not shy away from debate sparked by the pamphlet, printing anti-Common Sense letters throughout the first half of the year.7

In New England, the text was far more popular. In March, Abigail Adams wrote her husband John, that Common Sense was “highly prized here and carries conviction whereever it is read.”8 A month later, she added, “I long to hear that you have declared an independancy—and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies.”9

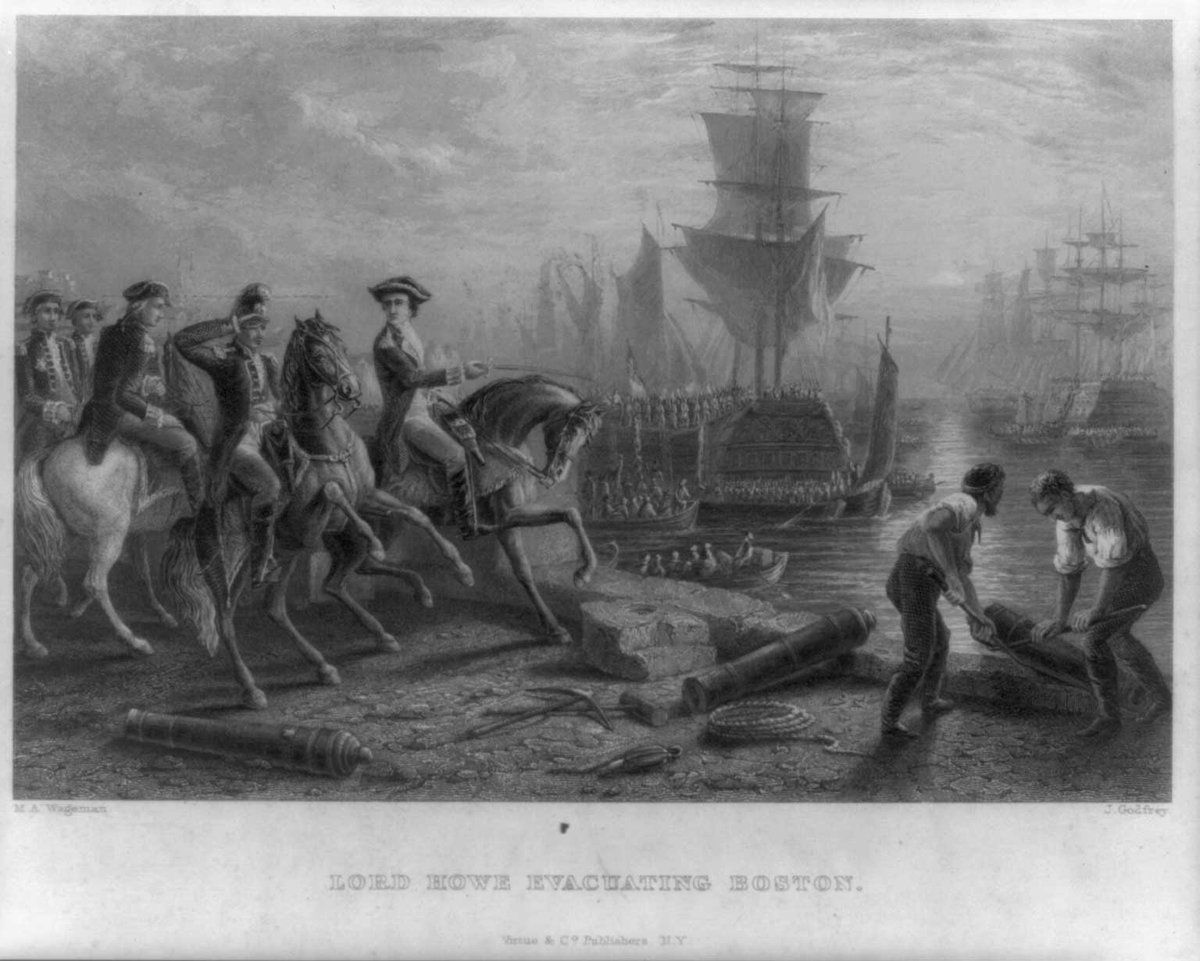

British Evacuate Boston

As Americans debated independence, war raged on. The Revolutionary War had begun in April 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Afterward, the British retreated to Boston, and American forces laid siege to the city. In June, Americans tried to prevent British troops from seizing high ground in Charlestown in what became known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. Virginian George Washington, who had been appointed commander-in-chief of the army two days earlier, arrived to take command of the siege in early July.

The British and Americans were at a stalemate through the winter. In March 1776, Washington took possession of Dorchester Heights, overlooking the town of Boston. By placing newly-arrived artillery at this strategic location, the Americans compelled British forces to evacuate the town. The victorious Americans maintained control of Boston for the rest of the war.10

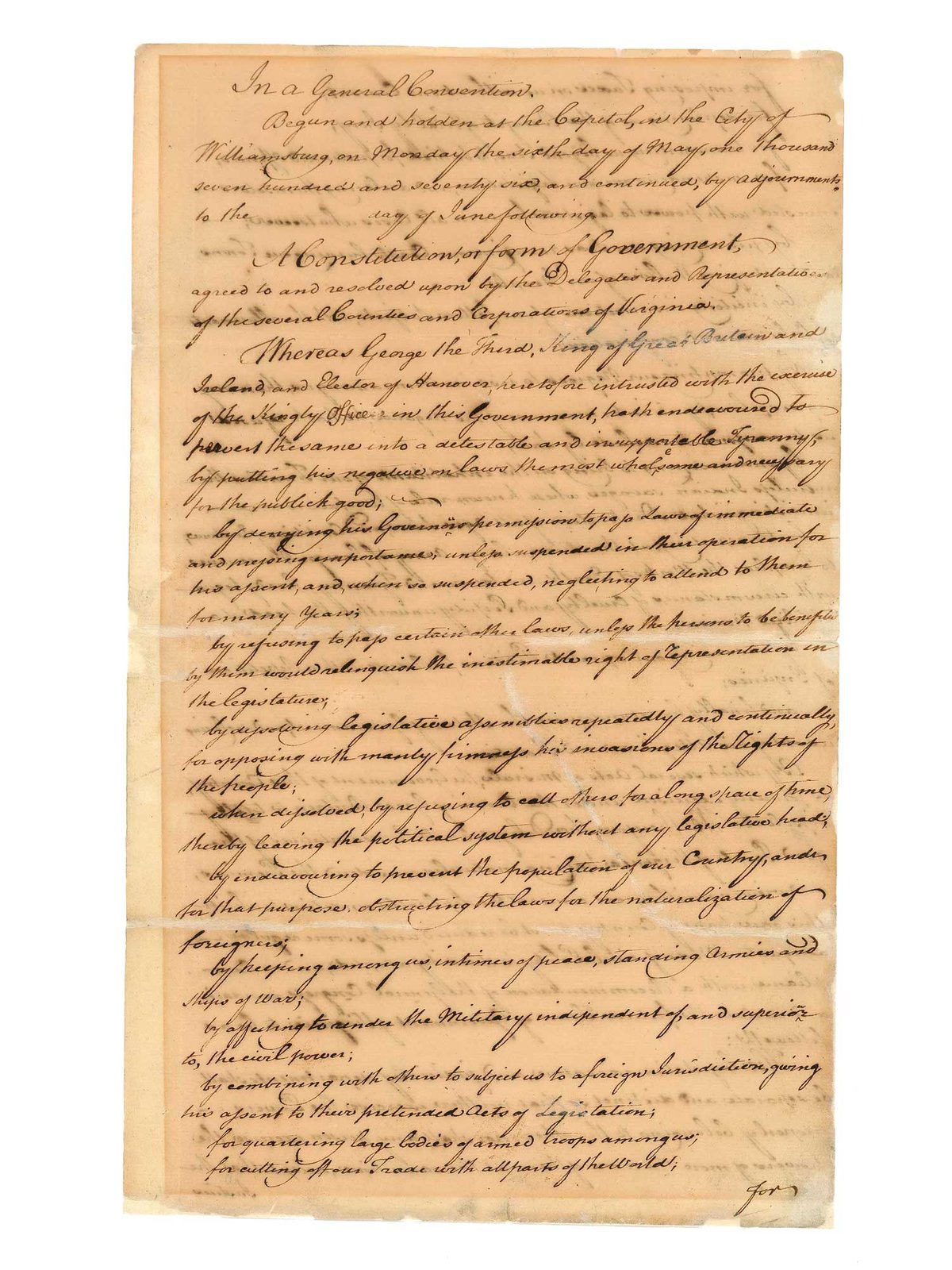

Fifth Virginia Convention Votes to Propose Independence

While the war shifted to New York, Virginia’s elected representatives gathered for the Fifth Virginia Convention in the Capitol building in Williamsburg. Revolutionary conventions replaced the House of Burgesses as Virginia’s governing body after the collapse of Virginia’s royal government in 1775.

On May 14, delegate Thomas Nelson Jr. introduced a set of resolutions that had been drafted by Patriot firebrand Patrick Henry, which denounced King George III and proposed independence. Delegates debated for two days, rewriting the resolutions with less incendiary language.11 On May 15, they voted to write a Virginia Constitution and Virginia Declaration of Rights, and to instruct their delegates to the Continental Congress to propose independence.12

The language of the independence resolution was a result of compromise. George Mason called the preamble “tedious” and “timid.”13 Patrick Henry wished it was more “pointed.”14 But the effect of their decision would be far-reaching, and very much pointed: it would result in the Declaration of Independence.

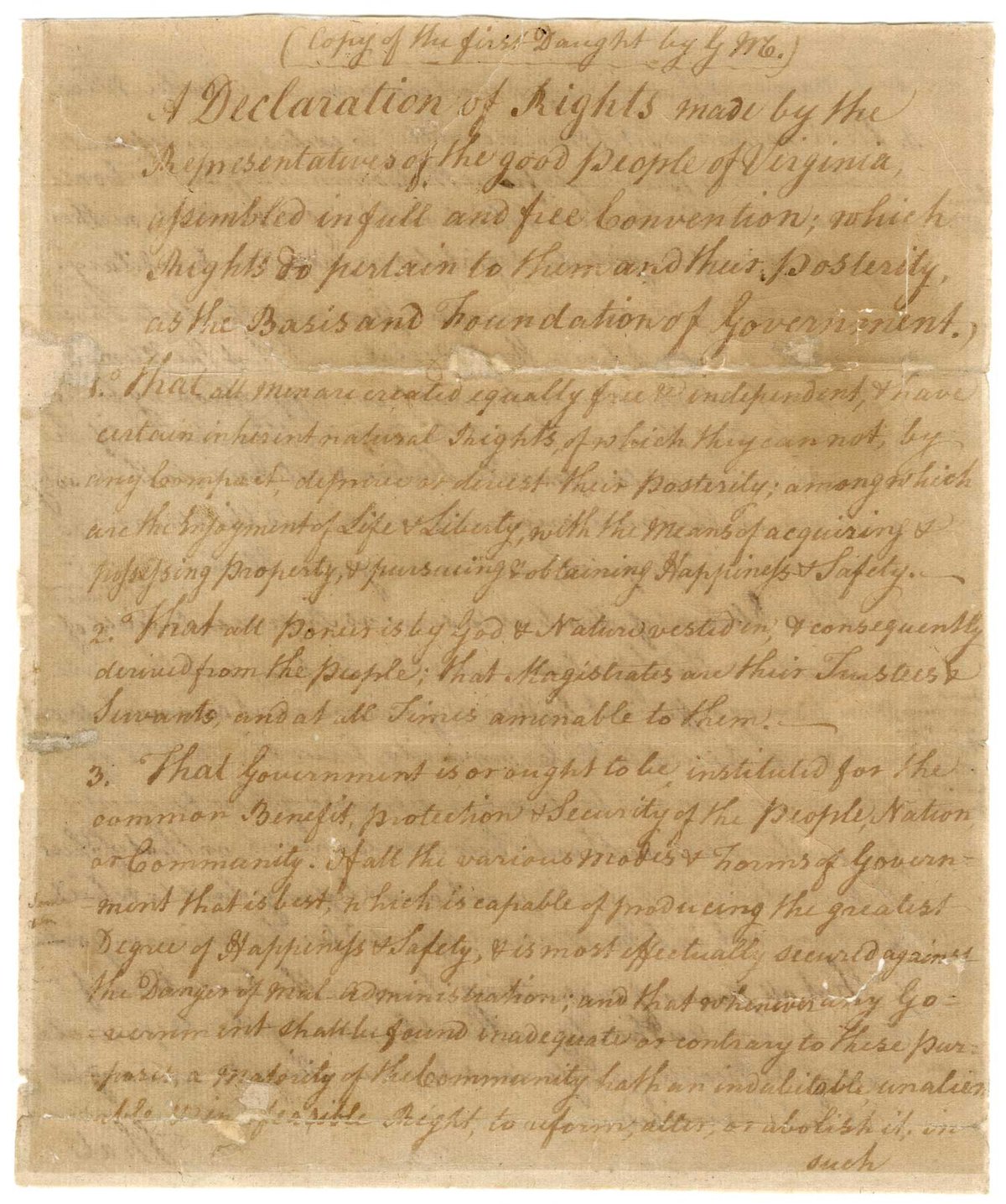

Virginia Declaration of Rights and Virginia Constitution adopted

The Fifth Virginia Convention continued their revolutionary work. The Virginia Declaration of Rights, drafted by wealthy planter George Mason, stated “that all men... have certain inherent rights,” including “enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”15 Thomas Jefferson referenced a draft of the document as he wrote the Declaration of Independence.16

George Mason’s initial draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights stated “That all men are created equally free & independent, & have certain inherent rights.”17 Virginia’s legislators, most of whom were enslavers, objected to this phrase for its obvious contradictions with the institution of slavery.18 The final version of the document limited this line by specifying that it applied to those who were in “a state of society,” which used the language of Enlightenment philosophy to exclude Black Americans from political rights because they were deemed to not be part of “society.”19

The Virginia Declaration of Rights would become one of the most influential political documents in America, informing not just the Declaration of Independence but also the Bill of Rights and countless other state declarations.20

The Fifth Virginia Convention also wrote a Virginia Constitution, which formally established Virginia’s new government. After its adoption, they chose Patrick Henry as their first elected governor.21

Declaration of Independence adopted

In the Continental Congress, representatives from thirteen colonies met to coordinate the war effort and make decisions on behalf of the colonies. Delegates from each colony were bound by the instructions they received from their legislatures. By early June, in part due to the influence of Common Sense, several colonies passed resolutions instructing their delegates to accept independence if other colonies did.22

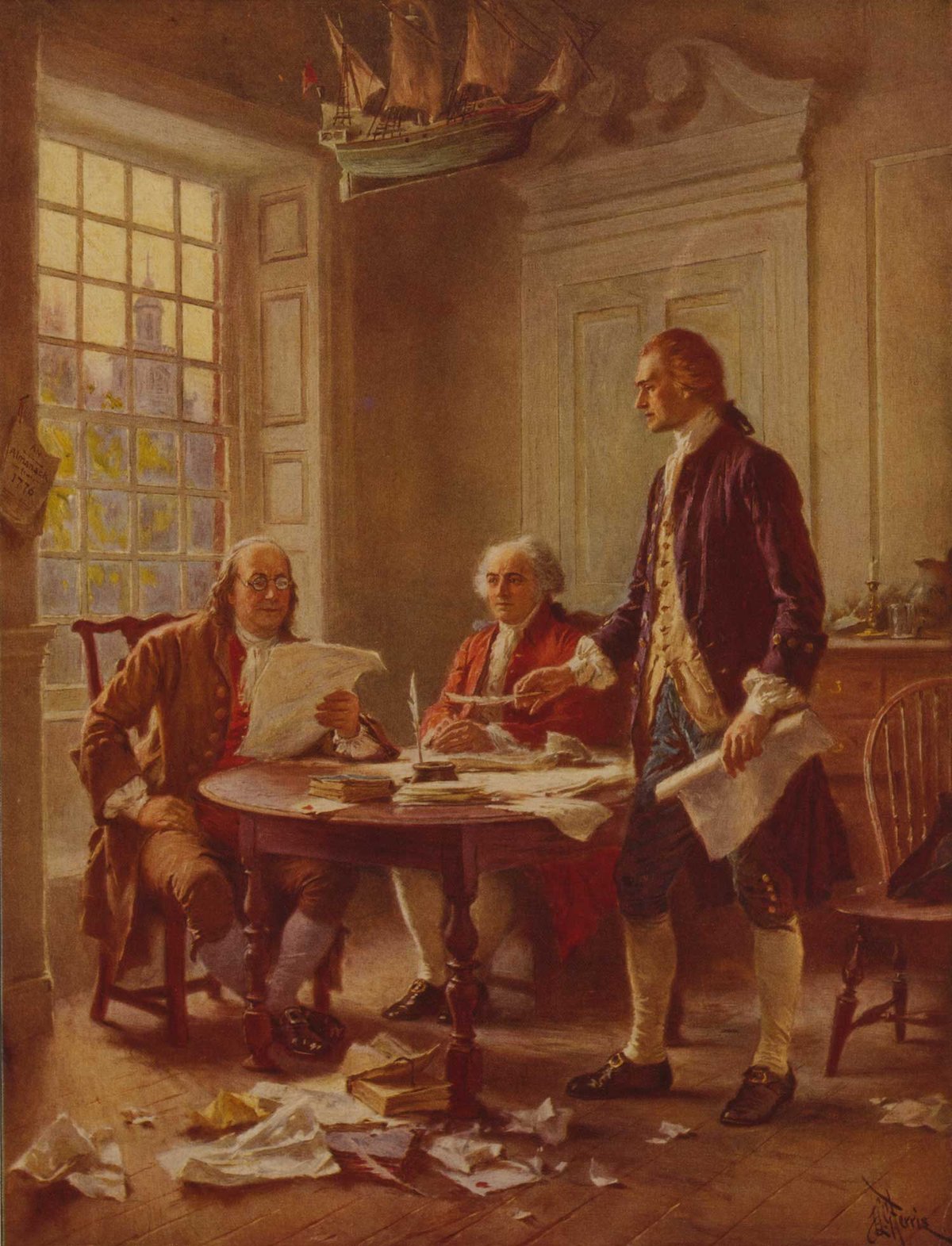

On June 7, acting on the instructions from the Fifth Virginia Convention, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee put forward a resolution "that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States."23 Congress appointed a committee to write a document declaring independence, who in turn chose Virginian Thomas Jefferson to compose the draft.24

The Continental Congress officially passed Lee’s Resolution on July 2, then started debating and editing the draft Declaration of Independence. After two days of debate and edits, they adopted the finished document, then had it printed and distributed across the new United States.25

The Battle for New York City

After the British evacuated Boston in March, and Virginia in August, the British and American forces turned toward New York City, a key port that connected the New England and Southern colonies.

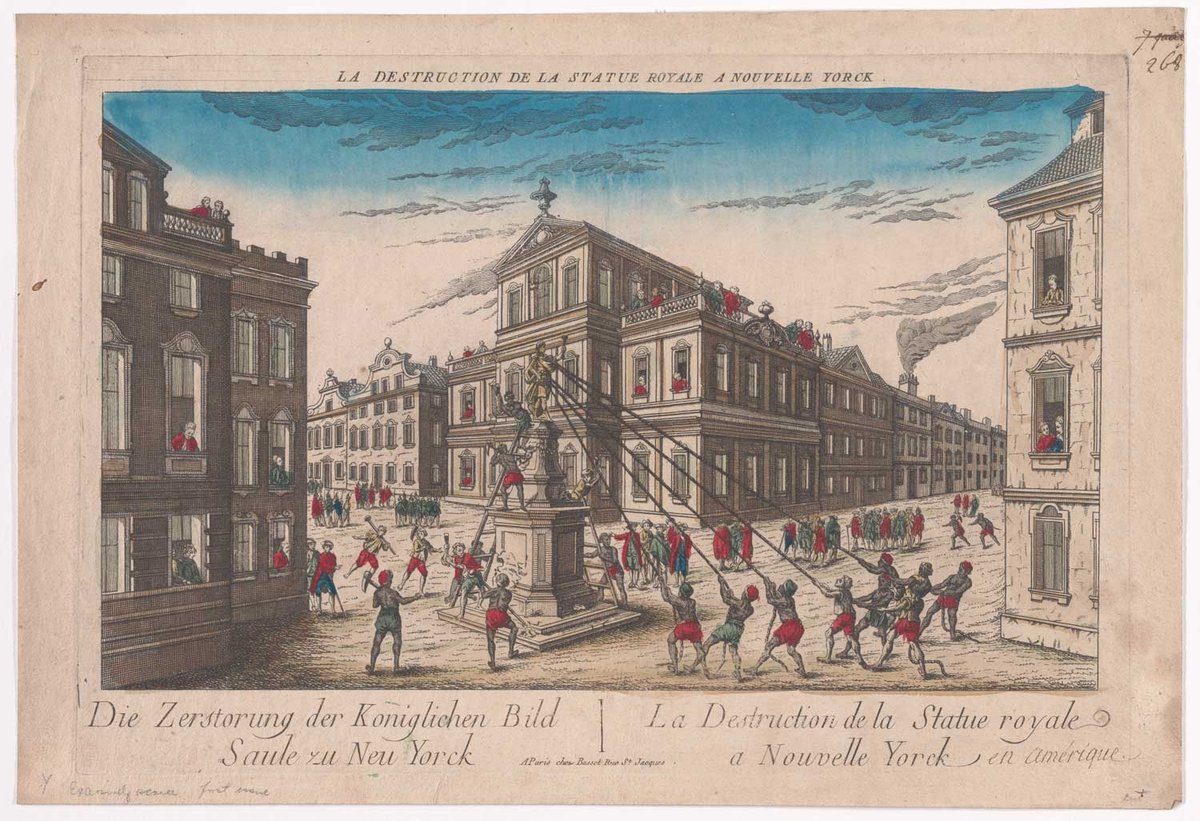

It was from Washington’s Manhattan headquarters that he ordered the Declaration of Independence read to American troops in early July. After the reading, a crowd made their way to a statue of King George III and tore it down. The remnants were used to make bullets for the American army.26

Meanwhile, the British amassed 32,000 troops to take control of the city from Washington’s forces. In August, they routed the Americans at the Battle of Long Island. In September, they invaded Manhattan, once again pushing Washington back in the Battle of Kip’s Bay. By October, Washington and his army had retreated to New Jersey. New York City would remain in British control for the remainder of the war.27

Revolutions in Williamsburg

The American Revolution didn’t just occur on battlefields. It happened as people in communities like Williamsburg established new institutions that rejected deference to authority.

The Anglican church was Virginia’s established church, meaning it was supported by the government. But by the mid-eighteenth century, dissenting religions like the Baptists were gaining popularity. Baptists were controversial, preaching about freedom and individuality, even to mixed-race audiences. Some Virginia leaders saw these teachings as a threat not just to the religious order, but to the very foundations of a slave society. But Baptist teachings resonated with free and enslaved African Americans, who found comfort in messages of equality and deliverance. A few miles outside of Williamsburg, a congregation of free and enslaved Black Baptists began worshipping. Because they operated in secret, there is little documentation of the church's early years, but according to the church's tradition they began worshipping in October 1776.28

While religious revival inspired some Virginians to seek a closer personal relationship with God, students at the College of William & Mary were inspired by the commitment to free inquiry that grew out of the European Enlightenment. In December, a group of William & Mary students formed a fraternal organization, Phi Beta Kappa, which was the country’s first academic honor society. Dedicated to intellectual inquiry, the students met at the Raleigh Tavern, where they held debates about scientific and philosophical topics.29

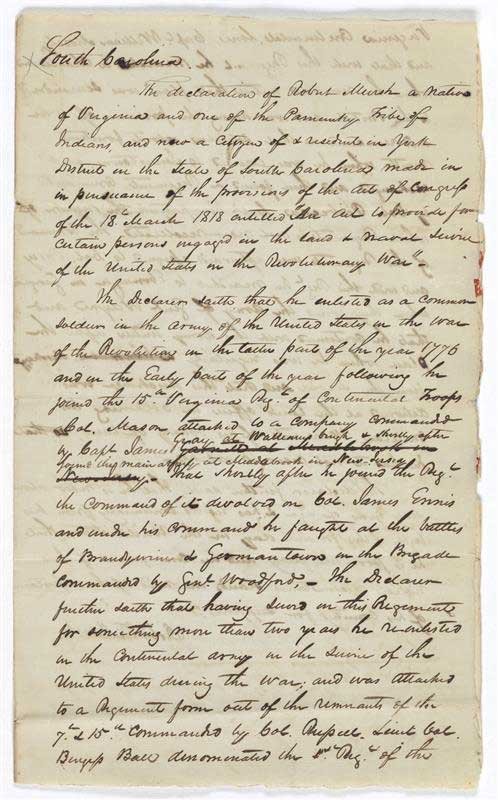

Even when fighting was concentrated in the north, war was a constant backdrop. In Williamsburg, military officials mustered soldiers and coordinated supplies. Robert Mursh, a member of the Pamunkey tribe and a student at the Brafferton Indian School, had spent years surrounded by revolutionary rhetoric and religious movements. In “the latter half of 1776” he and several other Brafferton students enlisted in the Continental Army in Williamsburg. Mursh served until 1782 and went on to become a Baptist preacher.30

Battle of Trenton

As the year neared a close, American prospects were dire. George Washington had lost New York City and was about to lose three quarters of his army when enlistments expired at the end of the month. From his encampment in Pennsylvania, he wrote in anguish, “I think the game is pretty near up.”31

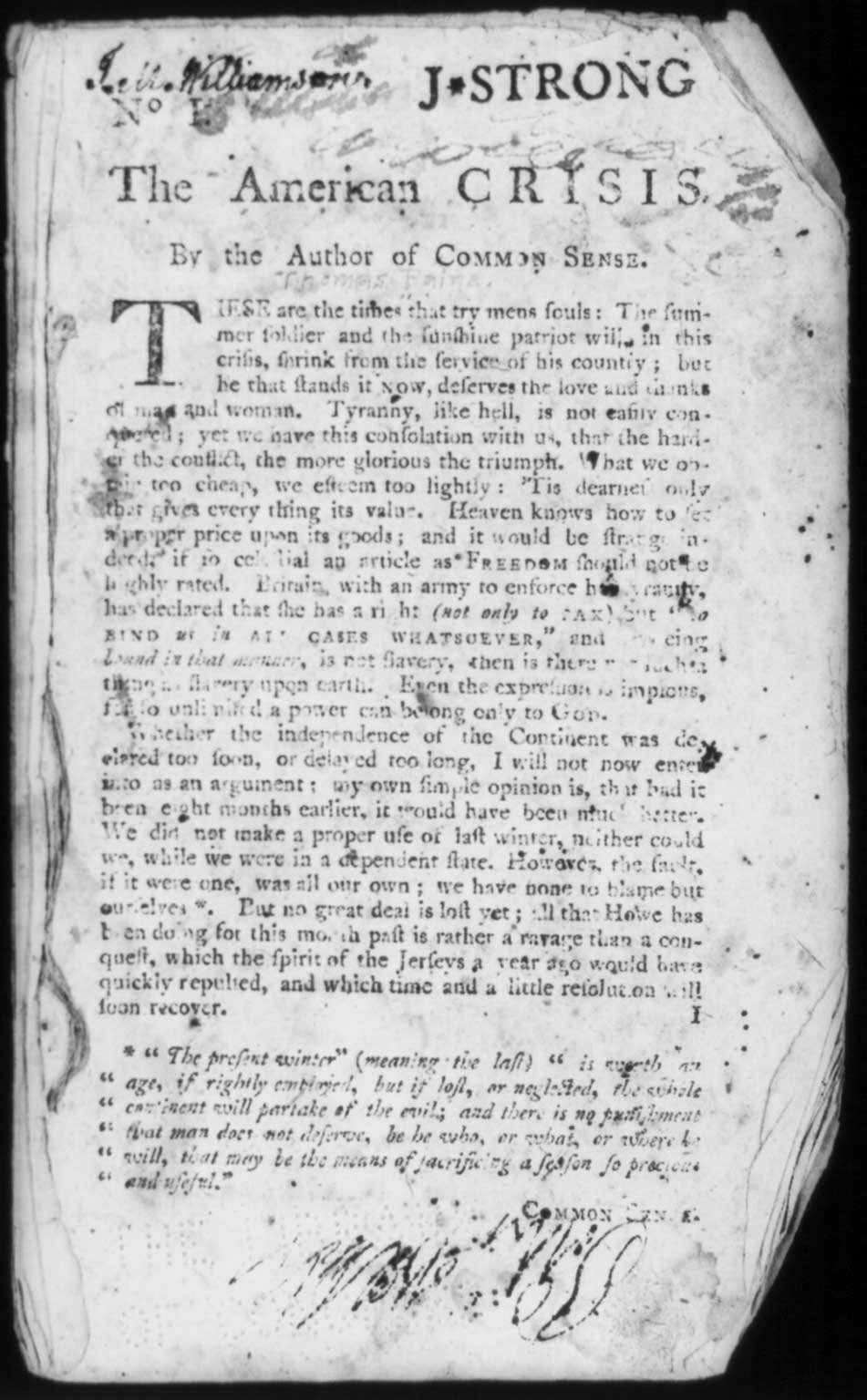

Thomas Paine once again took up his pen. “These are the times that try men’s souls,” he wrote in The American Crisis. “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”32 His words sought to rally Americans to the cause. The game wasn’t up just yet.

Days later, Washington launched a daring offensive at Trenton, New Jersey. Crossing the Delaware River, his army attacked unsuspecting Hessian soldiers (mercenaries hired by the King from German states) the morning after Christmas. The victory at Trenton, and a second victory in early January at Princeton, proved that Washington’s army still had a fighting chance at winning American independence. In the words of one British officer, the Americans had “now become a formidable enemy.”33

1776 in Review

Here's your 3-minute recap of what happened in 1776, and how Williamsburg contributed to the journey to American independence.

Sources

Intro footnote: Thomas Paine, Common Sense (Philadelphia: W. & T. Bradford, 1776), link.

- “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” National Archives, link.

- John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783 (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 80-84; Rick Atkinson, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (Henry Holt & Co., 2019) 191-3; Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), January 6, 1776, link; “Journal and Reports of the Commissioners Appointed by the Act of 1777, to Ascertain the Losses Occasioned to Individuals by the Burning of Norfolk and Portsmouth, in the Year 1776,” Encyclopedia Virginia, link.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (James Webster, 1817), 178-179, link.

- Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 84.

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense; Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 29-33. See also Trish Loughran, “Disseminating Common Sense: Thomas Paine and the Problem of the Early National Bestseller,” American Literature 78, no. 1 (March 2006): 1-28; Sophia Rosenfeld, Common Sense: A Political History (Harvard University Press, 2011).

- “Fielding Lewis to George Washington, 6 March 1776,” Founders Online, link ; “Landon Carter to George Washington, 220 February 1776,” Founders Online, link; Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” The Avalon Project, link.

- Trish Loughran, “Disseminating Common Sense,” 14.

- “Abigail Adams to John Adams, 21 February 1776,” Founders Online, link.

- “Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March 1776,” Founders Online, link.

- Rick Atkinson, The British Are Coming, 234-262.

- Brent Tarter and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence vol. 7 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 145-146.

- “Resolutions of the Virginia Convention Calling for Independence, 15 May 1776,” Founders Online, link.

- George Mason to Richard Henry Lee, May 18, 1776 in The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792, ed. Robert A. Rutland, vol. 1: 1749-1778 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 271.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry: Life, Correspondence and Speeches, vol. 1 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1969), 412.

- “The Virginia Declaration of Rights,” National Archives, link.

- Maier, American Scripture, 104.

- The Virginia Declaration of Rights (George Mason’s Draft), Library of Virginia, link.

- Thomas Ludwell Lee to Richard Henry Lee, June 1, 1776, Southern Literary Messenger 27, no 5 (November 1858), 325.

- “The Virginia Declaration of Rights;” Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 106-108.

- Maier, American Scripture, 165.

- “The Constitution of Virginia (1776),” Encyclopedia Virginia, link; Fifth Virginia Convention, Proceedings of Forty-seventh Day of Session, June 29, 1776, in Brent Tarter and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 7, part 2 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983), 649-660.

- Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 74-78.

- “Lee Resolution (1776),” National Archives, link.

- Maier, American Scripture, 99-102.

- Maier, American Scripture, 98-148.

- Atkinson, The British Are Coming, 348-50.

- Atkinson, The British Are Coming, 348-379. See also Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (Walker Books, 2002).

- Linda Rowe, “Gowan Pamphlet: Baptist Preacher in Slavery and Freedom,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 120 (no. 1): 1-31; Robert B. Semple, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Baptists in Virginia (Richmond: 1894), 148, link.

- The Original Phi Beta Kappa Records, including the minutes of the Meetings from December 5, 1776, to January 6, 1781, at the College of William and Mary, with notes and introduction by Oscar M. Voorhees (New York, 1919), link.

- Robert Mursh (Pamunkey), M804 Roll 1797 W.8416, Revolutionary War Pension Petition, 1818, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Buck Woodard, “Students of the Brafferton Indian School,” in Building the Brafferton: The Founding, Funding, and Legacy of America’s Indian School, Danielle Moretti-Langholtz and Buck Woodard, eds. (Williamsburg, Va: Muscarelle Museum of Art, 2019), 1329-136.

- “George Washington to Samuel Washington, 18 December 1776,” Founders Online, link; Taylor, American Revolutions, 169-172.

- “The American Crisis” in The Writings of Thomas Paine, vol. 1, edited by Moncure Daniel Conway, Project Gutenberg, link.

- William Harcourt to Earl Harcourt, March 17, 1777, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants, vol. 1, eds. Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1967), 524; Taylor, American Revolutions, 169-172. See also Friederike Baer, Hessians: German Soldiers in the American Revolutionary War (Oxford University Press, 2022).